20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years: 10. Raising Children

July 18, 2022 - Twenty years a foreigner in Croatia. Part 10 of 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years - raising children is a game changer wherever you are, but Dalmatia is special.

As all Dads will tell you, becoming a father is an incredible experience, a journey I could never have envisaged for myself. There have been many highs, a few frustrations and - especially now with two teenage daughters in the house - never a dull moment. But to have had the opportunity to bring up my kids in Croatia (and largely in Dalmatia) has been an additional privilege.

For raising children in Croatia is a very different - and much more pleasant - experience than I think I would have had back home in the UK.

The first major difference was the so-called Father's Test, a course fathers are mandated to go on if they want to attend the birth of their child (at least this was the case back in 2006). I was not averse to a little pre-natal classes, but the only problem was that the closest ones available to me on Hvar were in Split. Twice a week, for four weeks, beginning at 20:00, conveniently 30 minutes after the last ferry back to the island.

I decided to take my chances and see if we could negotiate something at the hospital in Rijeka, where we chose to have our kids delivered due to its reputation as the best for childbirth in Croatia. I wasn't looking to bribe anybody but was hoping that my charm and helpless foreign father routine might do the trick.

To my surprise, it worked, and I was told that for a fee of 300 kuna, I would be allowed to attend the birth. To my greater surprise, I learned that this was not even a bribe. I was given an 'uplatnica' pay slip to fill in and pay. But only at the moment that I was informed that my wife had gone into labour. With a receipt of payment in my hand, I hurried to the delivery room and knocked on the door. A doctor interrupted whatever he was doing to let me in, exchanging my receipt for some medical clothing. I was in.

There is something utterly euphoric about witnessing the birth of your child, and I beamed with pride at my wife and newly-arrived (and slightly purple) child. But my contact was short-lived. It was 01:05 on a Monday morning and within 3 minutes of the birth, I was told to go home and come back tomorrow. All of that euphoria and I was separated from my new family so quickly. I wanted to call someone but it was so late, I wanted to celebrate with someone but all the bars were shut, until I found a hole by the Rijeka Bus Station, where I sank a few celebratory drinks in the company of the local drunks. It was not an auspicious start to fatherhood.

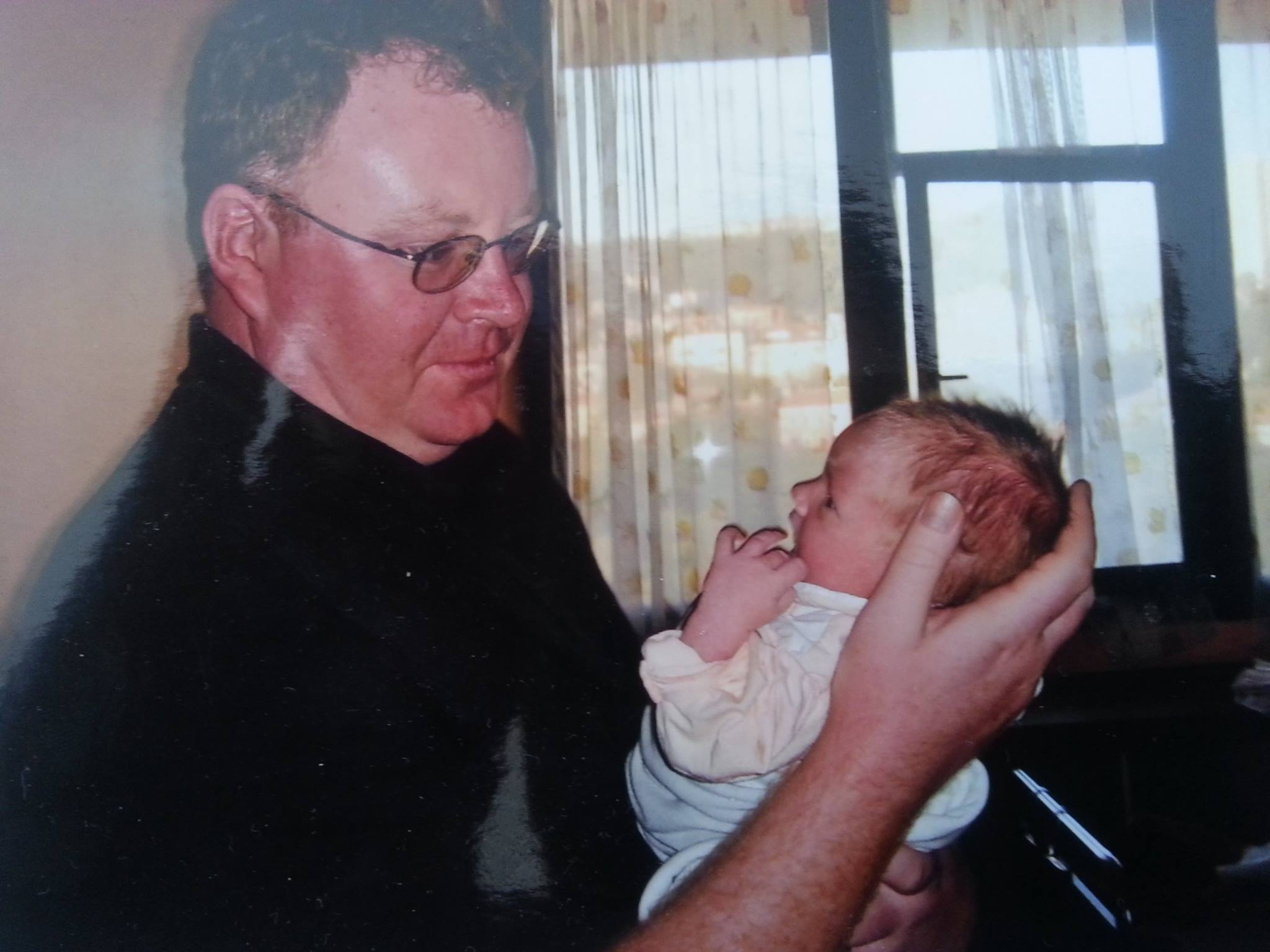

(The definition of mutual terror)

The journey home a few days later was terrifying. Having given us a couple of tips and a lesson in changing nappies, our new little princess was handed to us with a message of good luck. I think it was at that point we both realised just how life was going to be different. Taking the overnight ferry back to Stari Grad, we booked a cabin and laid our little treasure on the double bed while we watched every breath in fear that it might be her last. We just had to get back to the island, where my legendary mother-in-law, with four amazing children to her name, would come to the rescue with advice and support.

Just how much support, I was about to find out.

On the ferry, we joked about where exactly Nona would be when we arrived by car. Already waiting on the street, on the terrace etc. What we knew for sure is that she would be our saviour, both that day and for years to come. She was, of course, as close as she could possibly be, already on the street. And so we climbed the steps to our top floor apartment - my wife first, then Nona, then me with child in her basket.

We entered the apartment that cold October morning, but Nona had thoughtfully pre-heated the bedroom. In walked my wife, to be followed by Nona. My mother-in-law then turned around just as I was about to enter the bedroom, took the child and said:

"Bravo, Son. Your job is done. We will take it from here."

And so the door shut, leaving me a little lost for words and things to do.

I don't think it was intended in a bad way, or to exclude me from getting involved if I wanted to. I think it was more the way things are done in Dalmatian society. My mother-in-law was (is) amazing in all the help she gave, and I learned that Dalmatian guys tend not to get too involved in things at a very early age. I wanted to be different and was happy to do the nappy changes, taking the screaming monster in the night and being the assistant at bath time. After about six weeks, I had obviously done well enough to be entrusted to take the child out alone.

I had a property viewing on the main square with some American clients, and I put on one of those wraparounds which allowed me to slot the sleeping child in front of my chest. And off we walked together, just the two of us, for the property viewing. The Americans were waiting and cooing over the baby, and then the local owner came, started at me, and asked what was going on. I introduced my daughter.

"Congratulations, but where is the mother?"

"At home, having a well-earned break."

"Yes, but the child should be with its mother. We just don't do it this way in Dalmatia." He was clearly a little distraught over seeing a father alone with a six-week old.

I got into the habit of taking my daughter out for a daily cold one at my local cafe on the square. I had all the kit with me - nappies, wipes, spare clothes, towels, the feeding bottle and formula (once we moved on to the bottle). I trained the owner to bring the water at just the right temperature, and together with my beer, and we made quite the father and daughter team. Although I did notice that she feel asleep a lot as I told my stories, a trend which continues to this day...

I thought nothing of doing nappy changes on one of the empty cafe tables - we are all friends here - and life got into a jolly routine. I enjoyed our little outings together, as well as the compliments from some of the locals about what a good dad I was. Female locals, it turned out, and I learned I had a new nickname on the square - Najtata, or Best Dad. I wasn't too popular with the male counterparts, however. According to one female friend, I was letting the side down with all this nappy changing - the guys round here didn't do that kind of thing, and I was making them look bad.

(Hvar's mightiest river, the Slatina, which runs under Jelsa's main square. If your child has not fallen in over the years, you are not parenting correctly)

Life continued in that warm, safe Dalmatian way. It was easy to forget just what a paradise I lived in, a loving and totally safe environment for kids to grow up in. Love and devotion at home, and plenty of attention, and a little exploring on our daily excursions downtown. The first steps were taken walking from one cafe to another, all the way across the square. And once the walking came, suddenly life was a little more stressful. Especially as right next to the cafe was an open stream, which local cafes did not want to block access to as they used the water for their own purposes. It was considered a right of passage for a Jelsa child to fall in at some point, and both mine did under my watch.

I was at the other side of a packed cafe the day one of my daughters fell in. She had been talking to friends of mine and suddenly she put a couple of steps forward and in she fell. There was no real danger as there were bars to stop her sailing away into the ocean, but it was obviously not ideal. I raced to her aid and was there just after my friend. I took her through the side door of the cafe, stipped and dried her, then wrapped her in a sarong and presented her to the audience on the square about 30 seconds later, to rapturous applause.

"Now what are you going to tell her mother and grandmother when you get home?"

Sitting on the square with a cold one made you really appreciate the magic of growing up in Dalmatia. The innocence and the ease with which kids connected, even when there was often no common language.

The sense of community, spanning generations, with every child under the watchful eye of all and none at the same time. Mothers free to enjoy their coffee with friends, safe in the knowledge that someone in the community would alert them if there was a problem. Many was the time that a child fell and was in tears and had been fixed up before Mum got to the scene. I loved watching that sense of community in action. And when you also happened to have a cafe where the owners treated your kids like their own, then life was perfect indeed (top tip - Cafe Splendid on the Jelsa square).

Life was not all about what happened on the main square, of course. Coming from a very materialistic society, I found life in Dalmatia to be far superior in terms of teaching kids the value of things. The lack of commercialism was SO refreshing. When I first came to Jelsa, the first sign of Christmas was the tree going up in the main square on December 15. Christmas Day was a big family meal with 1-2 presents each, and then a nice walk in the December sun. Wonderful.

I learned to swim at the ripe old age of 29 when I took an adult swimming class (rather unreassuringly, 7 of those on the course had been on it before), and nothing has given me more pleasure than seeing the kids learning to swim from the age of two. With the Adriatic as their private swimming pool, long days at the beach and the chance to improve their swimming skills became the norm, and two young dolphins where born.

So too with their affinity with the land, something I never had with my bland tomatoes growing in Manchester supermarkets. Watching them helping their grandfather watering the vegetables in the garden, taking part in the olive harvest, helping to clean blitva with Nona, simple things that give them that closeness to Nature that I never had.

And picking a lemon off the tree in the garden for Dad's evening gin and tonic, obviously.

Nature, safety, love, community and a non-material start to life. Just some of the many reasons why I would highly recommend Dalmatia as a great place to start a family life. And with the rise in remote work, an option for more and more young families these days.

One of the things I was apprehensive about having children was the logistics of kindergarten and schooling. Friends in the UK would describe their daily routines, managing the kindergarten drop and collection with work and other commitments. And when they started talking about the price of kindergartens, it was a little terrifying.

And then there was Dalmatia.

Kindergarten, for a nominal monthly fee, starts from the age of 3 until school at the age of 7. It was a short walk down the steps to the waterfront - the kindergarten was in view from our terrace. And it was not long before the kids felt confident enough to do the walk themselves, waving at the terrace at regular intervals. A 20-metre stroll from my late morning beverage on the square to collect them and then back to the square for an hour before lunch, allowing them to play with their friends or chat to mine. Perfect.

That was an additional benefit of Dalmatian society for me. Kids were included a lot more in things in the community, and having confidence to talk to adults became second nature.

School was very similar, a little further to walk, but a walk that kids did solo from all over the town. Safe.

Dalmatia really is the very best place in the world to bring up children in the first part of their lives, and I am so thankful (especially to my wife and parents-in-law) that I had the opportunity.

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning - Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners will be out by Christmas. If you would like to reserve a copy, email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Subject 20 Years Book

20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years: 9. Dealing with Online Trolls

July 17, 2022 - Twenty years a foreigner in Croatia. Part 9 of 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years - the realities of life in the region, dealing with online trolls.

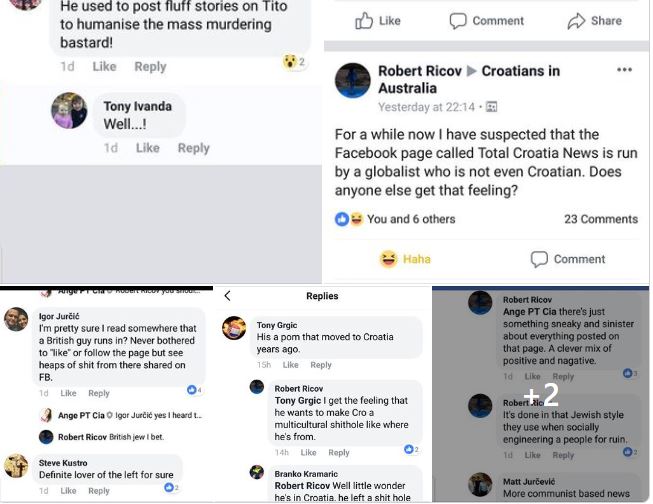

There is no feeling quite like coming home from the pub, logging on, and then finding your name being trashed on the Internet by a number of people on an online forum.

It happened to me for the first - but certainly not the last - time back in early 2004 when I was running a real estate business on Hvar. There was only one real place to chat about buying Croatian property back then, an excellent forum called Visit Croatia, and it was a great source of leads for me, as well as discussion points of the dos and donts of buying property in Croatia. Back in those days, the Croatian property waters were very murky indeed, and the forum quickly became the place to exchange information and to get some trusted leads. I was on the forum all the time, posting helping hints as well as trying to promote my business and beloved island.

After a tough day at the office, I retired to the square for a cold one or two, followed by a meeting with a client who had just agreed to buy an apartment in Jelsa. Another sale, another good day, I reflected as I came back home. One last check to see if there is anything new on the forum and then that was it for the night. I was horrified by what I saw.

I had been gone for about 2 hours, but somehow in that time, my reputation was being openly trashed. No less than 15 different people (curiously all first-time posters) started a discussion on how I was a fraud, only sold properties with unclean papers, added 50k to the price, and a host of other compliments. I started to panic.

Not only was all this untrue, but what kind of impression was this going to leave for future clients? I tried to defend myself, asking for evidence of what I was accused of, rather than just hearsay, but only more attacks, from new first-time posters, until the late Martin Westby, author of the guide to buying property and a respected authority on the subject, kindly posted this:

The threads miraculously stopped. I contact the forum, who looked into the posts and confirmed that they had all been sent from the same IP in Dalmatia. Welcome to competition in real estate, Croatian-style (and I suspect elsewhere too).

The threads miraculously stopped. I contact the forum, who looked into the posts and confirmed that they had all been sent from the same IP in Dalmatia. Welcome to competition in real estate, Croatian-style (and I suspect elsewhere too).

As shocking and upsetting as the experience was, I realised that nobody had died, the world kept moving, and life was more or less the same. A momentary online flashpoint is just that - momentary - and while it might be the centre of your universe, hardly anyone else will care. It is a hard thing to accept if you are sensitive, but it is the reality.

I have never been one to spend a lot of time in online discussions (I use social media mostly for promotion) and so my early Croatian experience with online trolls was forgotten until I started the Total Project back in 2011. Starting a portal about Hvar was a challenge I really enjoyed, but I was totally aware that I was not a native and did not know everything, nor did I understand all the cultural nuances. Given my ability to upset people without intending to, I would have to tread carefully.

I remember how sensitive I was to each and every comment in those first few months. If someone objected to something in the article, I might well go and change the article. I didn't want to upset people. And I didn't have to consider changing much. After all, I was writing positive stories about the island, celebrating its magic and discovering its secrets in such depth that even locals were commenting that they were learning things about the island by following my article via Google Translate.

But life - even on Hvar - is not perfect, and on occasion, I would write about a problem or issue. I was trying to portray the realities of life on the island, after all. I was shocked at the anger and level of abuse that was levelled at me.

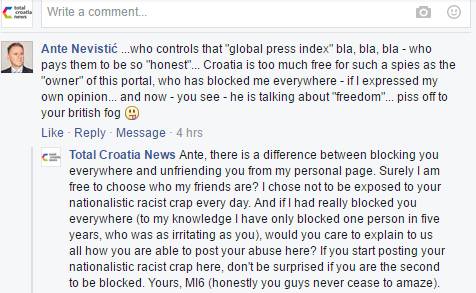

None said it quite as eloquently as Carrie (fake profile). The number of comments telling me to go forth and multiply back in the UK was actually quite impressive. Do I respond? Delete the comment? Learning from my 2004 property experience, I chose to ignore. When I posted a photo of Dubrovnik with the caption 'Dubrovnik is beautiful' to be told to f*ck off back to London as my opinions were not welcome, I realised I had clearly touched a nerve.

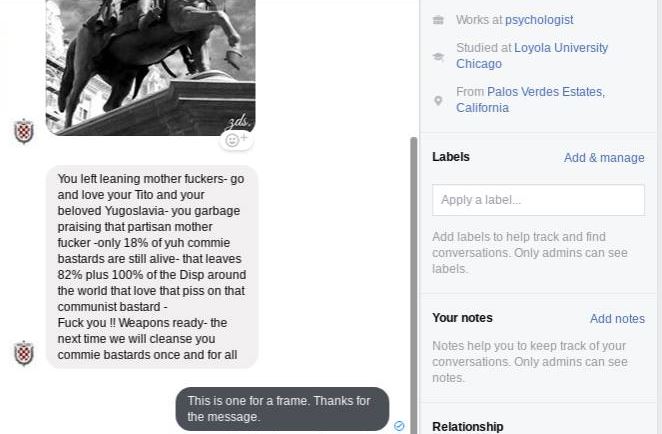

But things were only just starting, for the real fun began when I started Total Croatia News back in July 2015. Now we were reporting not on a happy tourism island bubble, but the daily news, the good, the bad and the critical. We even mentioned words like Tito.

And so it began...

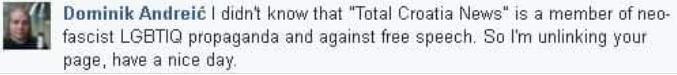

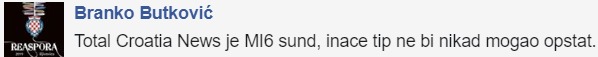

I was accused of being all names under the sun, and all things under the sun, and I had fascinating agendas, and some of the conspiracy theories were really quite outstanding. Some days, I was a fascist, some days a communist, and some days both at the same time.

I was particularly proud of this one - if someone can give me an example of neo-fascist LGBTIQ propaganda, I would be grateful.

After being initially shocked at the ferocity, I started to quite enjoy the abuse as well as fantasise about the lives of my abusers. What motivated them to pour such venom against someone they didn't even know? And who has the time and interest to comment on articles all the time? My particular favourite when we write about a celebrity arrival in Croatia, for example, is a common comment - Who cares? Well clearly you do, Sir, if you can take the time and effort to comment.

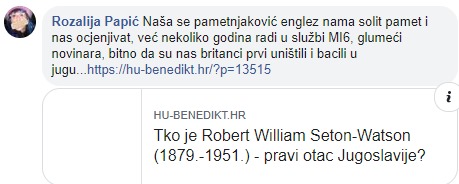

As much as I would like to follow all the comments on our various platforms, I just don't have the time, and I very rarely read - let alone comment - on them. And how to respond to those comments anyway? While I ignore most of the comments that I read on Facebook, there are a few little tricks I use which give me the kind of small and pointless victories that make life worthwhile, and I definitely have some favourite examples of abuse, which I wear with pride.

Top of the list is from an online forum in Australia a few years ago, where my name was trashed again. If I could summarise, the conclusion was that I am a 'Tito cock-sucking British Jew writing fluff to humanise mass murderers in the Jewish style when socially engineering a people for ruin.'

Quite a mouthful, but I have given instructions to have this written as my epitaph on my tombstone.

It is a good reason that life in Croatia has taught me not to take things seriously, otherwise I might have a wardrobe of orange clothing.

On the rare occasions when I do reply, there are two responses which have proved highly effective. The first is to reply with a simple one-word answer.

Indeed.

Nobody (including myself) really knows what I mean, and it kind of kills the thread in one word. It is neither positive nor negative.

With so much to read online (and life to be lived offline), I am constantly amazed at the people who object to TCN but continue to read it and then spend more energy telling me how useless we are. As I sometimes point out, there is no obligation to read it, and one sentence tends to stop the trolls permanently (a variation is above) - The only thing that gives me the strength to get out of bed each morning and carry on is the knowledge you can't stop reading.

I have yet to have a response (or any further trolling) to that comment.

In fact, it has been almost a year since I had some proper abuse, or a death threat (mistakenly typed 'death treat' by one admirer). I am clearly losing my touch.

Sometimes, however, one way to stop the trolling is to politely comment on the posts of your trolls, such as below.

I was genuinely disappointed when this former troll was overlooked to replace Zdravko Maric as Minister of Finance.

I decided to start a section on my personal FB, called Troll Friday, celebrating my trolls. Troll Friday didn't always happen on a Friday, but more when my online trolls felt the need to contribute. They never commented, and they were rarely heard from again.

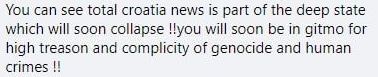

But nothing attracts more conspiracy theories more than what I am doing here in the first place running a news portal.

There can be only one conclusion.

![]()

Conclusive proof from Dubrovnik.

And Branko is not alone.

I must admit that the thought of me as some kind of Balkan Bond does make me smile, as does the suggestion that I am working for Soros, Putin and Greater Serbia all at the same time. Apparently, TCN has an agenda. I really wish it did - most days I get out of bed wondering what the hell I am going to write today.

My standard reply to this one is that I used to work for MI6 but now I freelance for Mossad.

So much energy into so many conspiracy theories.

So much fan mail for running a news portal.

Last year I put forward a suggestion to the army of keyboard warriors in Croatia. As they are proud Croats, why not agree that for every negative comment they place on social media, they commit to picking up a piece of trash from a Croatian beach? What a clean country we would have.

I think that the most important lesson I have learned from my relationship with online trolls in Croatia is you have a choice - to feed them and get mired in the negativity that this will necessarily entail.

Or to ignore them and focus on the many positive things in this fabulous country. Croatia sadly has a default negative mentality, a lot of which is exacerbated by online trolls and social media in general. Why not focus - as I advocated at Leap Summit a couple of years ago - to instead inject positivity into the default negative Croatian mindset? There is an awful lot to celebrate here.

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning - Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners will be out by Christmas. If you would like to reserve a copy, email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Subject 20 Years Book

20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years: 8. Business Meetings

July 16, 2022 - Twenty years a foreigner in Croatia. Part 8 of 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years - a new approach to business meetings.

One of the things that really confused me during my early days in Croatia, especially in the cities, was the fact that the cafes seemed to be pretty full almost all of the time. Did these people do ANY work, EVER? It seemed that the order of the day was to sit in the sun nursing a 2-hour espresso, watching the world go by with friends. How could the economy possibly achieve anything when most of the workforce was out drinking coffee all day?

It was one of my first lessons in how my Western mindset was very much at odds with my new surroundings.

"But don't you see that there is lots of business and work going on all around you," a local friend pointd out. "Cafes as offices for business meetings are part of the culture here. Look at that table, for example - big discussions. And that one. And that."

And when I took a closer look, I could see several business meetings taking place. Not long afterwards, I came across some research which claimed that 56% of business deals in Croatia are concluded over coffee (or something stronger) in cafes.

How civilised is that?

I started to do the same.

Not long after I moved to Hvar, I opened a real estate agency, Hvar Property Services. The 2003 Croatian property boom was in its infancy, and even though I did not know a lot about Croatian property, I knew people that did, and I knew how to deal with British and other foreign clients. How hard could it be...

Rather than investing in furnishing some swanky office, I decided to go local with my official meeting point, and I did a deal with my local cafe on Jelsa's main square to use it as an office. Lots of business for the cafe, a prime location for me, as well as a handy place to leave papers, or for clients to have a drink if I was running late (which I usually was - I was already becoming part-Dalmatian).

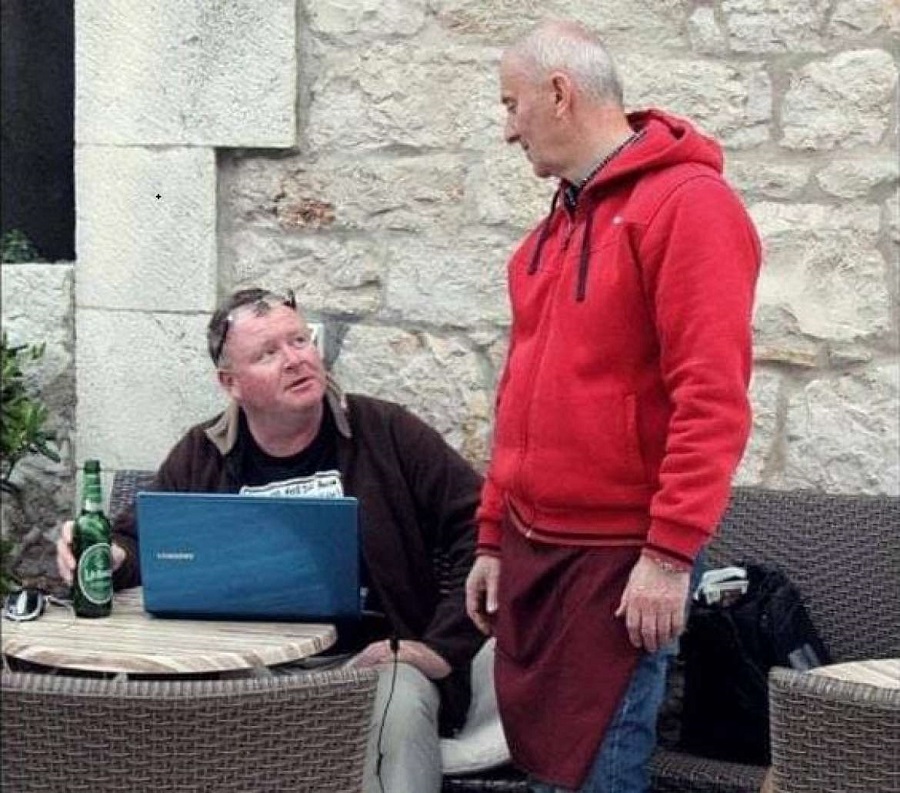

(The Office. Captain Nijazi provided excellent backend support for years at Caffe Splendid on the main square in Jelsa. Do not leave the island without trying the cherry strudel)

My new office was also part of my sales pitch. I would welcome my potential buyers with a cherry strudel and cappuccino, and we would marvel at the beauty, safety and wonder of life on the main square, then give them an overview of the perfect expat life on an idyllic Dalmatian island. The aim (and it worked) was to get them to see what looked like a wonderful lifestyle (it really was) and think that if I could achieve that, then why couldn't they?

After coffee and strudel, before we went to look at houses, I would drive them around the island to showcase its magic and make them fall in love with the island, then 1-2 properties before lunch, then a business lunch in a restaurant in the old town of Stari Grad, accompanied by wine. The seduction had begun, and I would always show my best property immediately after lunch, with great sales results. The end of the tour would return to where we started with a debrief over a drink. And then we would meet again in the evening to close the deal and discuss paperwork and next steps. Was I hanging out in cafes much of the day? Absolutely. Was I getting any business done? You betcha.

The cafe and business also have another function, one more sharp difference from my own culture. I wanted to meet the Mayor to discuss a business initiative, and so I made the logical step of going to his office to try and make an appointment. The secretary was evasive. he is away today, can you come back tomorrow and we can see. And so it went on for days. I vented my frustration with a local friend over coffee at my office on the square.

"Haha, but you really do not understand how to get a meeting organised in this society, do you? There is the mayor in the cafe opposite. He comes for his coffee every day at 11 to the same cafe. Go over tomorrow morning before he arrives, pay for his coffee, so that he will enquire who paid for it. Then walk across, wish him a good day and ask him when might be a good time to get 15 minutes with him. Over a coffee of course."

It is a little trick that works wonderfully.

After we moved to Varazdin, I managed to orgainse my time so that I was working from home 6 days a week, with one day a week in Zagreb. Arriving at 10:00 on the bus, leaving at 22:00 on the bus - 12 hours of solid cafe time - meeting, meeting, meeting, with the occasional social gathering if time permitted. They were some of my favourite days at TCN, for we covered so many topics that I would be bombarded with incredible stories and features from all sectors of Croatian society one after the other. And then I would have 6 days to digest and write about them, until I repeated the cycle. The relaxed backdrop of the cafe always helped the conversation move along.

And the flexibility of the cafe for business meetings should not be underrated. Digital nomads are all the rage these days, but I guess I have been one for 20 years now, working with a laptop and internet connection, wherever I found one. Sometimes meetings are cancelled, or there is a gap between business meetings. Or an article needs to be written urgently. In all those cases, order a cold one from the waiter and get to work. Business cafe life, unbeatable.

I should mention the dress code.

On February 24, 2001, I walked out of my local pub near Oxford with a small rucksack and a hitchhiking sign saying 'South Africa', walking out of my old life and starting completely afresh at the ripe old age of 32. I never looked back once, and you can read about my 9-month journey to South Africa in my first book, Lebanese Nuns Don't Ski. One of the many things I promised myself is that I would never wear a suit again, except for weddings and funerals.

And - for a full 15 years - I stayed true to that until a client offered me a job that required me wearing a suit for the evening. And then, really rather hilariously, given my lack of good looks, rounded physique and sartorial elegance, I was chosen to be the first-ever international male model in the illustrious 100-year history of Varteks. The reason was soon clear - my imperfections, for the fabulous campaign was called Imperfect Guy in a Perfect Suit. If I could look good in a suit, imagine what a suit could do for you.

If I was looking to avoid wearing a suit, then I could have chosen no better home than Dalmatia. With the majority of meetings taking place in cafes, so the majority of them saw me (and others) turning up in shorts in the midday sun. Even when there are more formal gatherings in Dalmatia, there seems to be a wide range within the dress code. There are those who wear suits to everything (apart from the most formal meetings), others who will turn up in a shirt even to weddings. My kind of space.

(Business planning with real entrepreneurs - planning the Entrepreneurial Mindset conference in a Zagreb cafe with Jan de Jong, Ognjen Bagatin, and the team from EY)

As I have never tried to win any sartorial elegance prizes, I saw no point in developing myself as the Brit with suit and tie at every occasion (despite my international model status), but a more casual shirt and slacks standard (with shorts for cafe meetings), bringing out the power suit only on the finest occasions. People seem to have accepted me that way, and I find it incredibly comfortable.

As is the whole culture and setting of business meetings in Croatia. If only doing the actual business was not so hard...

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning - Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners will be out by Christmas. If you would like to reserve a copy, email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Subject 20 Years Book

20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years: 7. Safety

July 14, 2022 - Twenty years a foreigner in Croatia. Part 7 of 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years - safety, one of the most underpromoted jewels of the Croatian way of life.

When I bought my house on the island of Hvar 20 years ago, several of my good friends were quite angry with me. What is wrong with you, Paul?

I smiled.

I could understand their concern, and I smiled again. Six weeks before buying the house, I was working as an aid worker in northern Somalia, with regular trips to the self-proclaimed Autonomous State of Puntland - the part of the Somalia where those fearless Somali pirates hang out and where they like to kidnap white boys for fun. I had an armed guard called Arafat every time I left the compound, and my job took me to some very remote parts of bandit country, some of which have still not really been discovered by Google.

(Life in the forlorn deserts of Puntland, Somalia, back in 2002)

Before that, I had been an aid worker in Rwanda straight after the genocide, worked in some questionable parts of the former Soviet Union soon after its collapse, and managed to get in the middle of a gun battle between the Israeli and Palestinians in the West Bank. There were only two words to describe me, decided my friends (incorrectly, as it happens) - war junkie.

And here was the latest proof - I had bought a house and decided to move to a war zone, Croatia.

The year was 2002 and I could understand (and appreciate) their concern, but I had to smile again. I don't think I had been to anywhere as safe, as calm, or as beautiful as this idyllic island, whose name I had learned just 2 days before. The day we arrived in Jelsa, we went to a tourist agency to find accommodation - it was peak season. A phone call was made and 5 minutes later, a cute girl no older than 6 with a few words of English turned up. The agency explained that she would sit in the front seat and guide us to her grandmother's rental property in the old town. Which she did with aplomb. And then she ran off to play with her friends.

A war zone indeed. The reality was, however, that Croatia had been at war just 7 years previously, although there was no fighting on the island, apart from a couple of bombs dropped on the airport (the influx of refugees and naval blockade is a different story) and I was still dealing with customer enquiries about safety and war on Hvar a decade later - perceptions take time to change.

And so began what on reflection was my first tourism promotion of Croatia. I sent photos and explanations. And invitations. I went to work in Hiroshima for 6 months, teaching English, French, German and Russian in Japan, and I invited friends to come and stay for free to experience my hidden gem of a war zone. The house was full, perceptions were changed, and several friends became regular visitors to Croatia, with one even buying his own house on the island.

I settled down into life in my new home, an amazing community that supported each other. Kids running around on the square under the watchful eyes of mothers enjoying a coffee in the sun, schoolkids the age of 7 walking halfway across the town to school unaided, young women walking home alone unhindered after midnight. There was no crime and I, liked most of my neighbours left cars and houses unlocked. I didn't carry a key in my pocket for years, and one of the many joys of living in such a safe environment was to find a bag of fresh fruit or vegetables gifted to you on the kitchen table by a neighbour returning from their field. I didn't go as far as to leave the windows of the car down due to the heat, with the keys in the ignition, but plenty of my neighbours did (and still do).

My kind of war zone.

From being on guard to sudden movements in a Somali town, I became the most oblivous person to security. This place was easily the safest place I had ever lived - it even felt safer than during my time in Japan.

There was almost no crime at all. And when there was, it made the regional news. One could imagine how dangerous this place was when the regional news had a front-page story in about 2003 on the theft of 50 litres on Hvar. Time to lock those doors.

Inevitably things have changed a little, and petty theft is now sadly an occasional reality, and so more doors are locked these days, but it is a far cry from having a knife pulled at me in the park in Manchester on my way home at uni. Indeed, in all my 20 years in Croatia, the biggest crime I can recall being a victim of was due to my unlocked car. We had been with friends in Hvar Town and they had gifted us a freshly-caught fish. I ran into town with the kids to buy a birthday present for a party they were attending, leaving the car unlocked, the fish on the back seat.

When we returned, the fish was gone, as was the kids' backpack containing their swimming things. So outraged was my 6-year-old that she insisted on calling the police to demand an investigation. The police said that they would do all they could, but that perhaps Daddy was at fault. She blamed me for the loss of the rucksack, and she insisted I always lock the car thereafter. She didn't seem to feel my loss of what looked like a VERY tasty fish.

Another key part of the safety in Croatia is the sense of community within generations and within itself. Mums know that if they have a coffee on the square that they can relax and keep just a cursory eye on the child playing. If the child goes out of sight, it will always be in the sight of a neighbour or friend, who will quickly check if something does not look quite right. I lost my daughter one day on the square when my back was turned and spent 5 minutes in panic searching. And then the phone rang - Teta Josipa from Me and Mrs Jones restaurant, the other side of the harbour. Your daughter is here, she wanted an ice cream, and when I asked her, she said she forgot to tell you. Are you coming too, or shall I send her back when she has finished? On the way a couple of neighbours had seen her walking alone and asked if she was ok - she explained she was going to visit her aunt at the restaurant for an ice cream.

Priceless.

And more and more people, especially from the Croatian diaspora, are beginning to make important decisions based on the safety of Croatia - moving back to the Homeland to bring up their kids in a much safer environment than they can find in Western cities. I have come across 5-6 Australian families with Croatia roots who have chosen Croatia over Sydney, for example, for one reason and one reason only - safety. And as the world continues to go nuts, and the culture of remote work grows, this is a trend that is only going to increase.

Another trend I am seeing on my travels is of increased real estate activity of white South Africans, who are looking to move from their home country due to the deteriorating situation back home. Croatia is the safest and most welcoming country they have found for their needs, and they are buying.

There is another very important (and rarely referred to) aspect of safety in Croatia - the kindness of strangers. There are countless examples of a tourist forgetting his wallet at a restaurant, or dropping it in the street, only for it to be returned with all money inside. In my case, I have one anecdote which for me perfectly explains why Croatia is one of the best societies to live in today for its values of decency and safety (we will leave the corruption and macro-theft of the nation's wealth aside, for this article is about lifestyle and personal safety), a really heartwarming story that you can read in full in Losing a Laptop in Zagreb: the Kindness of Strangers.

A few years ago, while living in Varazdin, I was on one of my business days in Zagreb, which included what turned out to be quite a boozy late morning office party. As I left and continued my day, someone packed a few beers in my bag that were left over from the party. I continued my day, with one bottle falling out onto the street as I got out of a taxi. I got home late, put the beers in the fridge and went to bed.

The next morning, I woke up a little groggy and with a writing deadline to meet. I made a coffee and opened my bag to fire up the laptop. The laptop was not there! I retraced my steps and wondered if I had left it in one of the cafes (I called each), and I even checked the fridge to see if I had drunkenly put it there. The laptop (and therefore most of my life) was gone. I had no idea what to do next.

And then a message on Facebook. Was I the Paul Bradbury who had lost a laptop in Zagreb yesterday? Joy at knowing the laptop was found, terror at how much ransom I would need to pay to get it back.

But this was Croatia, and I need not have worried. A very nice man had been walking with his friend for a coffee and found the laptop on a street in central Zagreb (where the bottle had fallen out), picked it up, opened it and found my name on the login details. A search of 'Paul Bradbury Croatia' indicated that I might be the owner. My new best friend told me that the laptop had suffered a little damage but that he had managed to fix that for me, and that I was free to collect it any time at his comic shop. I packed the beers back in the bag as grateful payment and gratefully headed to Zagreb. How many capital cities would that happen in?

Twenty years on, Croatia is no longer regarded as a war zone by anyone, but perhaps the time has come to tell people just how safe it really is, especially as this is a key factor for many in the remote work revolution.

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning - Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners will be out by Christmas. If you would like to reserve a copy, email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Subject 20 Years Book

20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years: 6. Moving Vegetables

July 14, 2022 - Twenty years a foreigner in Croatia. Part 5 of 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years - the fabulous culture of moving vegetables.

About 15 years ago, I was driving through Republika Srpska from Hvar to Belgrade to visit friends in my father-in-law's commercial vehicle. It had his name on the side and Split licence plates. As I tried to cross the border, the guard eyed my passport and me with suspicion. What was a Brit doing driving a car he didn't own with Split plates through this lesser-travelled part of the Balkans, and did I have anything to declare?

Nothing at all, I replied. He was not convinced and so I had to show him what I had, which was not much. Just my bag and 20 kilos of lemons and 20 kilos of potatoes, gifts for the family in Belgrade from the family field on Hvar from my father-in-law.

"You are bringing potatoes to Serbia? You think yours are better than ours?" Now he was really suspicious. We spoke in Serbian and Croatian, and I explained that they were a gift from my father-in-law to his relatives. The guard asked if he could take a few to try, and I told him to help himself. I was free to go. Almost.

"Just one more thing, Nije punac, nego tast." Punac is the Croatian word for father-in-law, tast is the Serbian.

A week later, I returned to Hvar by the same border, this time with about 20 kilos of paprika, a gift in the opposite direction. He just smiled.

It was one of the many examples of one of my favourite cultural practices in Croatia and the wider region - moving vegetables.

(My late father-in-law, whose tireless efforts in his family field, combined with the excellent cooking of his wife, produced the finest home-cooked food of my life)

I must confess that I had never thought about vegetables in my life until I came to Croatia (apart, perhaps, from my time as an aid worker in post-genocidal Rwanda in 1994 when my project was donated 1.5 million sachets of vegetable seeds with no packing list - it took 3 weeks to account for our gift), but vegetables (and fruit) loom large in my daily life in Croatia, and my 20 years in Croatia has made me completely rethink and appreciate local, quality food, as well as the cultural importance of transporting it to friends and extended family when driving from A to B.

Most of the credit for my enhanced passion for vegetables is due to my wife and her parents, whose family field has been the source of much of the goodness that I consumed during my 13 years on Hvar. The field was my late father-in-law's passion, and my wife and mother-in-law translated the fruits of the field into delicious and healthy local Dalmatian fare. Seeing my kids have an affinity with blitva (Swiss chard) at an early age was in direct contract to my fight every Manchester Sunday lunch to avoid the two Brussels sprouts on my plate.

Shortly after I moved here in 2003, I was in the grocery shop in Jelsa in November. There was a Brit, also living on the island, in front of me asking to buy some tomatoes - where were they?

"It is November," came the reply. "It is not the season. No tomatoes."

It had not occurred to her that tomatoes even had a season. Or to me. And if they did, when was it? Back in the Manchester supermarkets, tomatoes - very bland tomatoes - grew 24/7, 365 days of the year.

And so began one of the great transformations of my time in Croatia. I moved from being a spoiled city boy who could have any fruit or vegetable he wanted from a major supermarket chain to only being able to have fruits and vegetables when they were in season. But what I lost in availability, I more than made up for in quality. The wild asparagus may only be available for a few weeks in Spring, but WHAT a taste. (If you are an asparagus fan, you really have not tasted asparagus until you try the wild Dalmatian variety). The cucumber and tomato salads in summer are simple, but refreshing and so full of goodness. And I will never forget seeing my two kids return to Hvar after we moved. Seeing them breathing in the scents of that aromatic island was a joy to watch that November, but watching them head straight for the mandarin trees to pick a few mandarins to eat immediately was a wonderful sight. You don't get that experience when your mandarins grow in Manchester supermarkets.

After several years, I visited Manchester once more and visited a supermarket. I was shocked when I looked at the tomatoes. Where was the life, the colour. I bought some to try, but they tasted mostly of water. Dalmatia spoils you that way. Once you get used to wholesome homegrown Dalmatian vegetables, it is hard to find the quality elsewhere.

But the culture of moving vegetables was everywhere. I must admit I was a little confused one trip to Zagreb when I got into my car to find 30 cabbages and 10 litres of wine in the back to give to my brother-in-law in Zagreb. There was nothing wrong with that, but then a few months later, I found myself transporting a similar number of a different kind of cabbage in a different direction. Trips to Albania would always include a mandatory stop in the Neretva valley to stock up on watermelon, peaches and other treasures, and the roads of northern Croatia are always bountiful for bulk buying of pumpkins and paprika.

I love it.

And if nobody is driving from A to B, does that mean that moving vegetables comes to a halt? Absolutely not! Having moved away from the island, we would be regular and grateful recipients of large packages sent via post. Olive oil, mandarins, tomatoes, blitva, grapes, and a host of other goodness. Heaven. And we were certainly not alone. In addition to the post, other parents use the 'Balkan DHL' Service: Fast, Cheap, Reliable & Unbeatable, one of the finest institutions in south-east Europe.

The majesty of vegetables and the lifestyle that surrounds it is one of the many untapped treasures of Croatian tourism, as very few people locally have understood its appeal to city boys like me. One Hvar man who did was a friend of mine who runs a luxury tourism business. He told me about the moment when he finally understood the secret of successful tourism.

"I was with some rich New York clients in an olive grove for lunch and olive oil tasting," he explained. "One of them pointed to a lemon tree and asked if he could pick a lemon. I told him to pick six and forgot about it immediately. At the end of the week, he came to me to thank me for an incredible week, but he also wanted to tell me about the highlight. Picking those lemons. He lived in New York, had never seen a lemon tree, and had only seen lemons in shops, bars and restaurants. It was a powerful moment, and I realised that authentic experiences like that which are free and all around us here can be sold for top dollar."

And I can definitely confirm the magic of the freshly picked lemon. Can there be any better case for the Dalmatian lifestyle than sending one of the kids out to pick a lemon from the family tree in the garden for the evening gin and tonic on the terrace?

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning - Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners will be out by Christmas. If you would like to reserve a copy, email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Subject 20 Years Book

20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years: 5. Love to Hate to Nirvana

July 13, 2022 - Twenty years a foreigner in Croatia. Part 5 of 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years - the 3 stages of learning as a foreigner: love, hate and nirvana.

As with most things in life, my relationship with Croatia has changed over the last 20 years. I have been wowed by its beauty, felled by its bureaucracy, inspired by its brilliant people, depressed by the default negative mindset, and humbled by the kindness, hospitality and friendship on all levels.

As a foreigner, I don't think one can ever get to know a country or its people totally, and I am still very much on my journey to understanding certain aspects of Croatian society. Living in a different culture is of course fascinating, but it does come with its challenges, and as a foreigner, I have learned (as I wrote in an editorial a few years ago) that there are basically 3 Stages of Learning for Foreigners in Croatia: Love, Hate & Nirvana.

Foreigners interact with a country in different ways. In Croatia's case, the vast majority, 90% or probably more, come as tourists and leave wowed by the beauty I mentioned above. There is a saying I hear a lot here among the default negative mindset that Croatia is perfect for a 2-week holiday and horrible for full-time living. No jobs, corruption, nepotism, no opportunity. None of which one encounters on holiday. And so the vast majority of foreigners only reach the first stage - love. Great news for our tourism, as they will come back and enjoy their holidays in Croatia year after year.

Then there are those foreigners who choose to live in Croatia, the so-called expat community. And the vast majority of those tend to stay in the love Croatia section (they did move here after all) as they exist in their expat bubble, socialising primarily within expat groups, often not learning the language, and only having a cursory understanding of what is happening in Croatia outside their expat bubble. It is a very nice lifestyle, and one which I enjoyed for years. Indeed it was only after I started TCN some 13 years after my arrival that my idyllic expat bubble was burst.

And so - at least in my opinion - the vast majority of foreigners who visit Croatia are blissfully unaware of the realities of the daily grind in Croatia and are very positive as a result. For many years after I reached stage two, I was a little envious of them, for once you get to stage 2, it is almost impossible to go back. But that envy disappeared when I discovered stage 3, nirvana.

The second stage of learning, which I call hate, occurs to a much smaller number of foreigners who live in Croatia and decide to deepen their relationship with the country, often by opening a business. Now firmly out of their expat bubble, they are exposed to the full force of Croatian bureaucracy and many of the illogical laws that are applied. Suddenly that day at the beach is exchanged for being sent from office to office in search of a signature. And the more that they immerse themselves in business, the more they understand how Croatia really works, and why so many young people are leaving - I firmly believe that lack of economic opportunity is not the prime reason, rather corruption and nepotism.

Suddenly, that relaxed Adriatic lifestyle in the sun has changed, eyes are opened to the daily grind and the realities of life here, and there is a greater understanding of what local people are going through.

In my case, it truly took me 8 years in my little Hvar bubble to realise that things worked (or didn't) the way they did for any other reason than laziness on the part of officials. That all changed around the time I started TCN and when I learned about the Cult of Uhljeb.

Like almost all foreigners, even the ones who spoke Croatian, I had never heard of the Croatian word 'uhljeb' until I read it in a title about me and a public official on a national Croatian news portal back in 2015. When I asked on my Facebook page what it meant, there were lots of responses, and it felt like my relationship with some of my Croatian friends changed that day. It was almost as though I had discovered their guilty secret and that I was now descending from my expat bubble and entering their world of Croatian reality. If you want to understand exactly what an uhljeb is, I wrote an explanation some time ago - Welcome to Uhljebistan: A Foreign Appreciation of the Cult of Uhljeb.

Running TCN got me a lot more involved with Croatian politics and the Croatian media, neither of which are particularly happy or positive places to be. What had happened to my perfect Hvar bubble and idyllic life on the most beautiful island in the world? It was lost forever.

Or was it?

And then things changed, or rather my mindset changed. A coffee with a Croatian friend of mine who ran an adventure tourism business. She told me that she checks in on the politics about every six months and finds nothing has changed, whereas I was obsessing about it and covering it on a daily basis and being drowned in its negative messages. In fact, she told me, she stays in Croatia for her friends, family and nature - she is often hiking in the mountains - and contact with the state and the day-to-day grind is kept to a minimum. She accepts that Croatia is far from perfect, but she chooses to live in her own bubble. Life is not easy, money is hard to come by, but she has peace and is only surrounded by positivity. A much better lifestyle than emigration.

The longer I ran TCN, the more people I met. And in the search for positive stories (and there are MANY in Croatia, the majority of them are sadly left untold), I met SO many other people like my adventure tourism friend. They love Croatia and could not live anywhere else, but they protected themselves by surrounding themselves with only positive people, blocking out all the negativity in the media and elsewhere. Most did not want to be featured in the media or discovered or bothered in any way. Rather than spend all day complaining about the injustices in the Mighty State of Uhljebistan, they just accepted that that was part of the price of living in Paradise.

It was a pivotal moment in my Croatian journey and I was reminded of the powerful words of that famous prayer:

Accept the things you cannot change, have the courage to change the things you can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

I was at the Gates of Nirvana. I just needed to coin the sentence, the explanation, the justification (a little like I had done taking 15 years to define the essence of succeeding in Dalmatia in the first part of this series - Do not try and change Dalmatia, but expect Dalmatia to change you).

And then it came to me.

Choosing to live in Croatia for the lifestyle is a little like being an alcoholic in Norway. The alcoholic chooses Norway for the lifestyle, for a beer costs 10 euro and he could drink 5 for the same price in countries like Croatia. But he wants to live in Norway and so chooses to pay the expensive alcohol tax.

And so too in Croatia. One can still advocate for change, but rather than consuming all one's energy in negativity, complaining about the way things are, in my head I now pay my uhljeb tax and - just like the alcoholic in Norway - I am free to enjoy the best lifestyle in Europe and focus on my positive bubble.

Paradise indeed.

Nirvana.

The third stage of learning for a foreigner.

Not only did I have my perfect Hvar bubble back, but also a state of mind and peace with Croatia that makes this truly the best place I have ever and will ever live.

It took me 15 years to figure out the uhljeb tax and expecting Dalmatia to change me. If I can save you 15 years of frustration and pain, I will be very happy indeed.

Come and join, the bubbles of positivity in Croatia are insane.

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning - Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners will be out by Christmas. If you would like to reserve a copy, email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Subject 20 Years Book

20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years: 4. Croatian Wine

July 12, 2022 - Twenty years a foreigner in Croatia. Part 4 of 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years - a new approach and appreciation of wine in Croatia.

Soon after I moved into the apartment above my soon-to-be parents-in-law, my father-in-law took me down to the garage. He was a lovely man, a real man of the soil, and the hardest-working person I ever met. We had no language in common back then and so I was curious as to what we would be doing in the garage.

At the back of the garage were three stainless steel tanks of about 200 litres each. The one on this left had three letters written on it - POL. A gift for me. He took an empty 1.5 litre empty plastic Coke bottle and filled it with his own red wine. It was very, very drinkable. And so life was very pleasant, as that bottle was refilled over and over again until one day nothing more came out of that magical tank. It was one of the many generous gifts he gave to all.

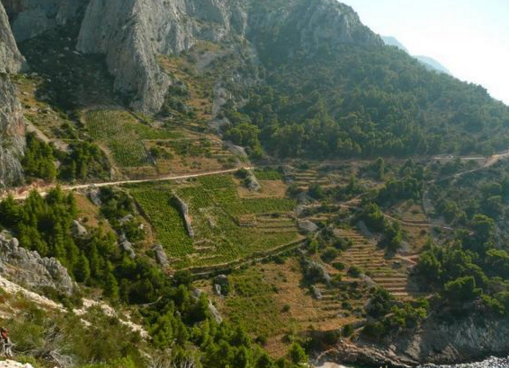

(The steep vineyards of southern Hvar, where some of the best Plavac Mali is produced)

And it was far from the only time I drank wine from an unmarked plastic bottle. In fact, I have probably drunk more wine from plastic bottles than proper wine bottles in my 20 years in Croatia.

For Croatians do wine in a VERY different way to the rest, and it is easily the most interesting wine country I have had the pleasure to explore. On so many levels.

I should explain that I have a little background in wine, having worked in our small family business importing wines from small family growers from France, Italy, Spain and Germany. I knew my Puligny Montrachets from my Chablis Grand Cru, my Cru Beaujolais from my Beaujolais Nouveau, as well as the taste of the few lesser-known quality grape varieties in the classic regions, such as Bourgogne Aligote, and the only time I would drink chilled red wine was a St Nicholas de Bourgueil on a hot summer's day.

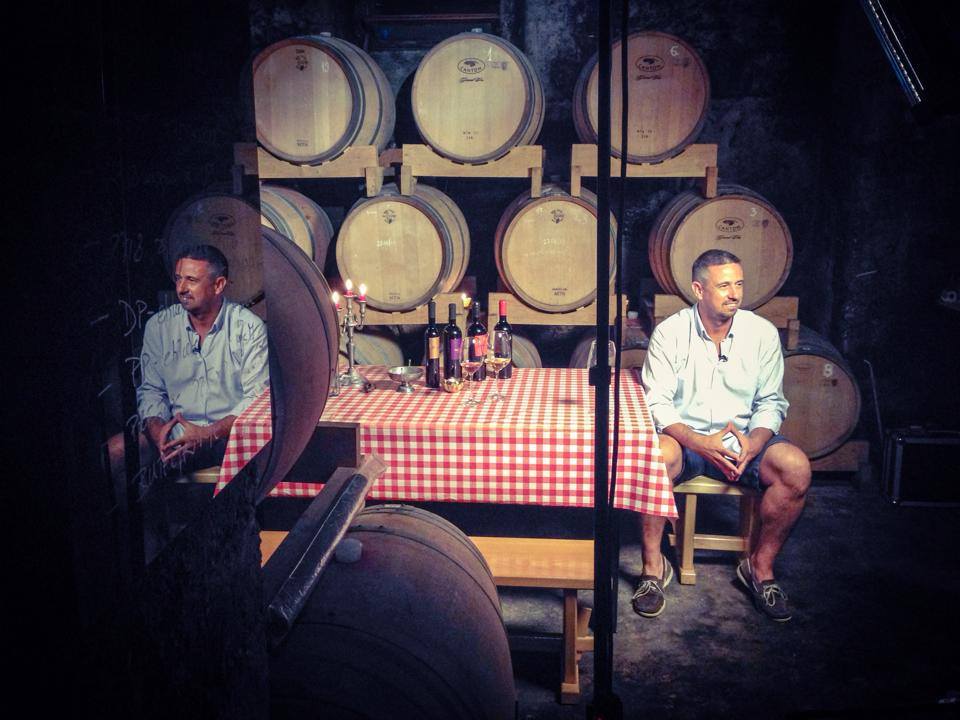

(The Andro Tomic wine cellars in Jelsa are one of the more impressive Croatian wine tasting locations)

And then I came to Croatia, whose wonderful - and relatively untold - wine story was the total opposite of everything I had come across elsewhere.

My Croatian wine journey did not start well. When I first arrived 20 years ago, the most common wines on the tables of Jelsa's restaurants were either house wine, or litre bottles of Faros red and Faros white. After a couple of attempts, I decided to stick to beer. Hvar may be a beautiful island, but its wines were not its stong point, I concluded.

How wrong I was!

(Candlelit wine and olive oil tasting in the cellars of Ivo Dubokovic in Jelsa)

It was only years later when I started researching for the first edition of Hvar, An Insider's Guide, that I realised just what I had been missing. Not only was Hvar a wine island, but it had so MANY fascinating stories. A wine tradition dating back 2,400 with vines and olives brought by the invading Ancient Greeks, which are tended in much the same way today on a UNESCO World Heritage Site called the Stari Grad Plain. How cool is that? And while I may have been drinking average table wine in restaurants, those in the know were appreciating the quality. Among the Hvar wine portfolio was a hearty red which was served in a 3-star Michelin restaurant in Holland, an organic gold medal winner in Germany, and a Grand Cru which was a champion in Bordeaux. Indeed the wine scene on Hvar was so interesting that a British Master of Wine, Jo Ahearne, moved over from the UK to become the first MoW to produce wine in Croatia - Hands from London, Grapes from Hvar.

And it was the grapes from Hvar that was the biggest surprise.

As I started to research the Croatian wine scene, I was stunned. This small country apparently has more than 130 indigenous grape varieties. Among them was one called Crljenak Kastelanski, which researchers at the University of Davis proved in 2001 to be a 100% DNA match for the powerful Californian red, Zinfandel. That's right - the birthplace of Zinfandel is Dalmatia.

And the undisputed king of indigenous grape varieties, at least on Croatia's islands, was Hvar. Its best-known variety is a white called Bogdanusa - which translates as 'a gift from God' - but it is by no means the only one. Other varieties that only grew on Hvar, I learned, included Prc, Darnekusa and Kuc. But there was more to come.

Commercial private wineries are a relatively new thing in Croatia, given the socialist Yugoslav past, and they only began to emerge around 1990. Most of the wine was produced in large cooperatives, where the quality often suffered in favour of quantity (but with major exceptions, such as that organic gold-medal-winning PZ Svirce on Hvar). This to me is one of the most fascinating parts of the Croatian wine story. Small growers finding their way without experience of Western marketing and usually without much infrastructure. And each has a different vision and area of interest. One can visit Hvar, for example, and visit 10 wineries and wonder if you are on the same island.

One of my favourite little wineries to visit is a guy called Teo Huljic in the back streets of Jelsa. He only produces about 7,000 litres a year, much of which he sells in his adjacent restaurant, but his passion for wine and the island's heritage is addictive. While Hvar has several grapes that only grow on the island, Huljic has discovered and is preserving several more. He is the only winemaker in the world who produces a 100% Mekuja (around 600 bottles), and has even managed to bottle 70 litres of Palaruza, a very drinkable white that not even my father-in-law had heard of, and Google only had one entry on when I researched it.

(Teo Huljic conducting a tasting of Hvar's indigenous wines)

And if you are a real wine enthusiast, where else in the world can you island-hop and try grape varieties indigenous to a particular island? After sampling the indigenous viticultural joys of Hvar, check out Vugava on Vis, Dobrota on Solta, Zlahtina on Krk, and the supremely unpronounceable Grk in Lumbarda on Korcula.

Grk is also home to my favourite Croatian wine story. The white wine variety (and my favourite in Croatia) only grows on the sandy soils of Lumbarda, a few kilometers from Korcula Town. As such there are only 33,000 litres a year produced, which puts a strain on supply as it is one of the top restaurant white wines in Croatia. As wine tourism developed, a rule was introduced that each person tasting could buy a maximum of 2 bottles per visit. Otherwise the supply would quickly run out.

The story - which has been verified locally - goes that a member of the Kennedy family ordered the best local white wine in an exclusive Dubrovnik restaurant. So impressed were they that they sailed to Korcula the next day and visited the winery for a tasting.

"Fantastic wine. We will take two pallets."

"Unfortunately, that is not possible, Sir. We only sell a maximum of 2 bottles per person."

"We are the Kennedy family. We will take 2 pallets."

"We are the Grk family. Two bottles only."

I liked that. They apparently returned to the Dubrovnik restaurant and bought the whole supply. At restaurant prices.

Croatia does have magnificent wine estates with lots of tradition in addition to these small growers. One of the finest wine experiences is Croatia's most eastern vineyard, Ilocki Podrum, in Ilok. Purveyors of wines to the British Royal Family. More than 11,000 bottles of Traminac 1947 were ordered for the Queen's Coronation in 1953. The two other bottles in my hands are the same wine, later vintage, for the weddings of Princes Harry and William. And there are still a few bottles of the Queen's '47 - but it will set you back 55,000 kuna.

And don't miss Croatia's oldest winery in Kutjevo, where the oak barrels literally tell the story of the town's 800-year history.

As impressive as these estates are - and there are several more - it is the cosy and unpretentious approach of the hundreds of Croatian winemakers who are pushing forward in their own corners of the country, and with increasing success.

The best white wine I have tried in Croatia? A lesson in just how exciting the Croatian wine scene is. I came across it in a village in eastern Croatia I had never heard of until I arrived - Dalj. And the winemaker - Jasna AntunovicTurk had quite the story. The first female winemaking owner of a vineyard, her passion is Grasevina, but the wine which blew me - and the judges at Decanter - was her 2013 Chardonnay. It would not have been out of place in the premium vineyards of Burgundy.

And it is not just in wine-growing regions of Croatia that you will meet outstanding wines - they are to be found in the most unexpected places. Meet the only winemaker in Split - in an atomic bunker!

The majority of Croatian winemaking is a much less formal affair, and many families in Dalmatia, for example, make their own for family consumption. And wine purists may look in horror at some of the practices they will encounter, but it is more proof that Croatia does things differently.

Red wine and still water is a drink of choice for many in Dalmatia - bevanda. Head to the continent and you will no doubt be introduced to Gemist - white wine and sparkling water. And if you want to go really local, check out the annual Biklijada in Vrgorac, where they celebrate the rather curious bikla - red wine and goat milk. My father-in-law used to drink it as a child, very nourishing apparently. As is another Dalmatian speciality I have yet to try for some reason, Prosek with a raw egg. Great for protein for the little ones.

Croatian wine has given me many memorable nights over the last two decades (as well as a few where the memories are a little hazy). Warmth, friendship and authenticity take precedence over protocol and presentation in many cases. Croatian wine is, for me, a symbol of the quality and diversity which makes the Croatian experience so unique, and it has certainly changed my perceptions about wine over the years.

Why not come and have a glass yourself - bring your own plastic bottle for the true rustic experience.

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning - Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners will be out by Christmas. If you would like to reserve a copy, email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Subject 20 Years Book

20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years: 3. Bureaucracy and Mindset

July 11, 2022 - Twenty years a foreigner in Croatia. Part 3 of 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years - meet the bureaucracy and mindset double act.

I am a child of the Soviet Union.

No, this is not some revelation that I have been leading a double life all these years, more an explanation that my exposure to the socialist/communist bureaucratic mentality started more than 30 years ago with my first forays into Eastern Europe before the Berlin Wall came down and then a summer in Moscow when the Soviet Union was still a thing.

And therefore, for almost 35 years now, absurdity and the absurdity of bureaucracy have been a part of my life. There has been much frustration along the way, as well as much humour, but I have come to accept that living in this part of the world comes with the reality that there is an official mindset reality that exists and is hard to change, and absurd rules with no rhyme or reason are blindly enforced. Why, for example, did I have to spend almost £100 a year in Croatia ordering a new birth certificate every year for my temporary residence? A birth certificate proves you were born, but in Croatia only one which was less than 6 months old was valid. You can either rail against them or accept them and get on with life.

I chose life.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, I returned to live in Russia for 15 incredible months, in some rather far-flung places in that vast country, and the full force of post-Soviet bureaucracy, absurdity and logic was all around me. One of my best friends was a former captain in the Soviet special forces, and I asked him once for his favourite examples of absurdity in his country.

"I think it was the canteen in the military barracks where we were stationed once. There were two things that stood out for me. The first was that the canteen staff would take their lunch break at lunchtime, which proved to be a challenge feeding us. And the second was the spoons. There had been a continuous theft of spoons from the canteen, so it was decided to stop the thief by deterring him from stealing. The order was given - and implemented - to drill a hole in the middle of the spoons. This made the spoons worthless but they weren't much fun when trying to eat soup, but I can't deny that the thefts stopped overnight. A little like Stalin's Five Year Plans, there are many ways to present a story."

When I moved to Croatia in 2002, I had not been in the region for several years, mostly in the UK. Although I had come from Africa, which has its own approach to bureaucracy (my favourite story was of the BBC reporter at Nigerian immigration. You don't have a visa - you must pay US$50. Yes I do, here it is, pointing to the visa in the passport. I can't see it, comes the reply, as the immigration officer rips the page out of the passport. Fifty bucks or no entry).

It didn't take me long to get back into the socialist bureaucratic mentality. No, we can't accept this form, as you need to buy some tax stamps for 10 kuna, and no we don't sell them here. This page is missing a stamp. As a foreigner, you are in the wrong room. The list - and the frustrations - went on. I was shielded initially from much of the bureaucratic process by my long-suffering Croatian girlfriend and now wife, who entered the battle on my behalf with her superior language skills and better cultural understanding.

But gradually I got to do some of the battles myself, when I was left alone to deal with the absurdity and frustration myself. And I have to admit, I am having rather a lot of fun.

You see, there are two ways to approach Croatian bureaucracy, at least from where I am sitting. The most popular option is to vent against it, express your frustrations to anyone who will listen, and share all the negativity and anger with the world. This is an understandable and common reaction, but not one that have ever used. For the simple reason that there is rarely a positive result, other than friends and family expressing sympathy.

I have never seen any point in complaining on social media, as people are generally not interested in hearing other people's problems - they have enough of their own. But social media I have found to be a FABULOUS tool when trying to deal with Croatian bureaucracy. It is one of my three strategies.

I first learned of the power of social media, not to rant but to find solutions, about 15 years ago. The Internet went down at home, and my wife called to find out when it would be restored. We will come in 7 days, came the reply, hardly an ideal situation for a blogger on a deadline. I had to take my mobile office to a local cafe.

The next day, I was in the (smoky) cafe again on deadline, this time with my young kids, as my wife was in Split. It was clearly an intolerable situation and one which would last at least another 6 days. There MUST be a solution to this, surely? A Croatian solution? I took to Facebook, explaining my situation.

Does anyone have a Croatian solution for my problem, my post concluded.

What happened next was extraordinary, and my Internet was restored in half an hour.

A friend sent me the name and email of the PR lady for the telecom company, explaining that she hates bad press and that if I politely explained my situation and that I was a British blogger writing about Croatia, perhaps she might be helpful. I did as my friend suggested, received a reply with apologies within two minutes, and my Internet was restored in an hour. This was followed by one more apology and an invitation to contact her directly if I needed anything else. It was the finest example of customer service in my 20 years in Croatia.

There is a postscript.

A few months later, a friend of mine with a tourism agency on Hvar called me. It was the season, his Internet was down, and he had been told it would be 9 days until they could come and fix it. What had I done to get mine fixed and could I help? I sent a polite email to the PR lady, copying my friend, reminding her that she had invited me to contact her if there was anything more she could do. Three hours later, my friend called me to invite me to dinner - his Internet had been restored.

But I love using social media for other reasons too, and with successful results. Many Croatians are really interested in what foreigners think of their country, especially ones like me who make the insane decision to move here by choice when everyone is emigrating. Most foreigners here only scratch the surface of how this country works (or doesn't work, depending on the viewpoint), and so when a foreigner takes to social media with the topic being bureaucracy, it is time to reach for the popcorn. It is also a time when Croatians are very generous with their contacts and advice, and rather than getting frustrated with bureaucracy, one can find a quick solution.

Against my better judgment, I opened a new company, a jdoo, last year. Everything went incredibly (and I mean incredibly) smoothly until the very last hurdle, which should have been the easiest of all. As a foreigner with permanent residency owning a business, my bank in Varazdin informed me that I could no longer open a bank account in Varazdin, but would have to do so in the head office in Zagreb, around 80 km away. The year is 2021. Absurd in this digital age and after such a smooth experience opening the company, but I decided to go with the flow - I was due in Zagreb the next day and would pop in and open the account. My wife suggested I check if I needed an appointment and called ahead. Indeed I did - and the next free spot was in THREE weeks. That's right. In 2021, a bank I had been with for 18 years with my personal and business accounts (and so knew who I was) were offering the best option to open an account of a 3- week wait and 160 km round trip.

I asked on Facebook if anyone had any suggestions, and a lively debate ensued. The following day, I met Nenad from Raiffeisen Bank who had told my wife over the phone that he could open the account in Varazadin (without the need to go Zagreb) in one hour. As we shook hands, I levelled with him.

"Nenad, let me be open with you. I am a frustrated journalist. If you can really open this account in less than an hour, I will make you a superstar." You can read what happened next in Opening a Croatian Business Bank Account as a Foreigner... in 46 Minutes.

There are two postscripts. Five people contacted me to thank me for the article, explaining that they were now in the process of moving their business from my bank to Raiffeisen. And Nenad called me to thank me - head office in Zagreb had called him with a commendation.

I was having so much fun that I even started a section on TCN (which I must get back to) called Croatian Bureaucracy, a Love Affair.

One of the great benefits of trying to publicly find solutions to absurd Croatian bureaucracy is that kindred spirits, many of whom have been fighting their own battles, enter the fray. I was driving a car last year ago with the number plate above and I paid for SMS parking in Varazdin, then in Zagreb the folliowing day. I was surprised to get parking tickets from both. I took a closer look at the number plate - the 0 were both exactly the same, but were they both numbers or was one a letter?

A friend who has dedicated much of his life to the minutiae of Croatian bureaucracy came to my aid and we eventually sorted things out, but not before discovering that the confusion was deliberate. A rather fun read in Croatian Bureaucracy, a Love Story: 1. The Car Licence Plate.

But the real battleground in Croatian bureaucracy is with officials in their offices. Some are outstanding, but quite a number have no interest in their job, or being disturbed, and least of all you. Especially if you are a foreigner who probably can't speak Croatian. There are computer games to be played after all. And it was in this context that I learned my biggest lesson back in 2013 when I went through the (hellish) ordeal of importing a car from Germany. That I did it with a monstrous hangover made me all the more proud that I survived the day.

I think I had to go to about nine offices in all - stamp here, signature, there, form filled out here, you know the drill. Office number 6 was where it happened. I knocked. No answer. I opened the door and saw a heavy-set official through a cloud of cigarette smoke at his computer. After a moment, he looked up, looked at me, looked through me, then returned to his important work (which turned out to be a computer game).

We have all been there. How could I get the stamp I needed?

"Sorry to bother you," I began in my best Croatian. "I need a stamp from you to import my car."

Silence. No reaction, save from the click of the keyboard on the computer game.

"Also," I went on, "I am a writer researching a story on how the Croatian customs house has changed since EU entry. Would it be possible to give me a quote, and could I perhaps take your picture?" I lifted my camera in hope.

"No picture. No quote. Give me the paper," he shouted. Stamp. I was out of the room with all I needed 10 seconds later. There was just enough time to catch a glimpse of his computer screen and the important work he was doing.