Analysis: Coronavirus in Croatia Compared to Other European Countries

April 21, 2020 — I received some great observations from a colleague, so I asked him for permission to share them with you. He says that he is getting a little nervous about all sorts of things, and has started to keep his statistics for some European countries that are of interest to him. The statistics end on 04/18/2020.

Otherwise, click here for daily detailed visualizations of coronavirus data in Croatia, and for all our texts on this topic, see the keyword “koronavirus”.

The following are quotes and charts from a colleague.

The point in all the charts is that it makes no sense to express the absolute number of infected or dead or whatever by country because we mix potatoes and locomotives. It does not matter that Germany has over 80 million inhabitants, Belgium 11 million and Croatia 4 million. So I reduced everything to a million inhabitants and then you see things differently than what is said in the media.

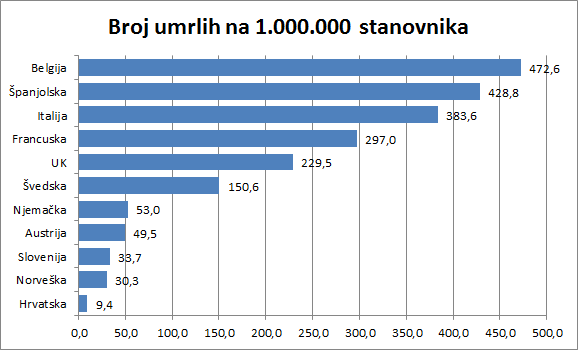

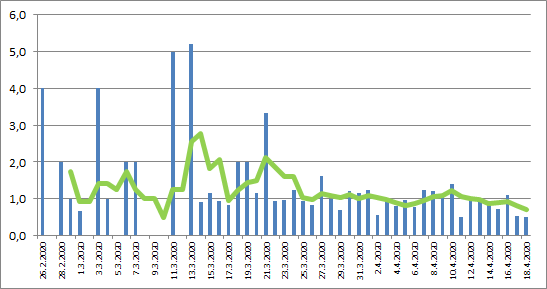

Coronavirus deaths per million population

This is the number of deaths from/with coronavirus. Of course, we don't know if all these figures are correct (the source is Johns Hopkins' coronavirus database), but let's say they are accurate enough to see the proportions.

So there is no doubt how good Croatia is relative to the others in terms of deaths. Comparing this with Sweden, the situation is 16 times worse than in Croatia. And we can't compare Sweden to Croatia in any way, and especially not to the strength of the health system or GDP.

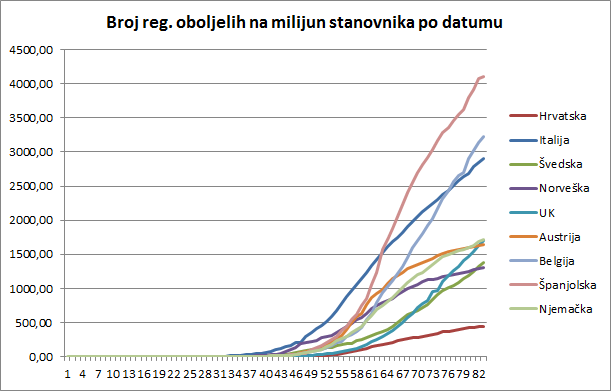

This is a comparison of the number of confirmed infections (the actual number of infected people we do not know) again reduced to one million inhabitants. All start on day 1, even though the first patients registered in different countries on different dates. Here you see too much of the forest to make out the trees. In any case, one can see here who has straight curves, whose grew exponentially, and who has inflected. Who is the best? Croatia.

Number of registered patients per million population, on the same dates, regardless of the fact that the first patients registered in different countries on different dates

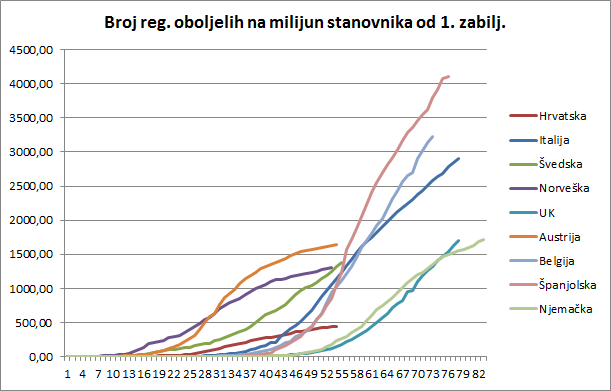

This to me is a far better overview. The curves here are not on the same date, but each begins on the date when the first diseased was registered in that country. Here you can see when who reacted and how.

Number of registered patients per million people, on the dates when the first patients were registered

Of course, Spain has the worst curve in terms of relative numbers, but it slowly (unfortunately, very slowly) calms the epidemic. Italy is also slowing the epidemic. Belgium has a terrible situation, but the curve is flat. The worst is the UK, which has barely evened the exponential curve. These countries, including Germany, have waited a long time without serious measures with few infected.

The second group responded quickly: Austria, Norway, Croatia.

Of course, Sweden cannot be said to have truly responded. This is a special case.

It can be seen that, although it had a very rapid expansion of infected, Austria reached an inflection very fast - sometime in the 30th day from the first case, and calmed the epidemic. So there are reasons to loosen the measures.

In Norway, the spread of the infection started very shortly after the first patient, but relatively slowly, and has an even better result than Austria. Germany is also calming down its epidemic, similar to Austria, but the inflection is only about the 62nd day.

Who is the best? Croatia. Importantly, Croatia imported its first patients from Austria and Italy. But it reacted before both countries, a far larger and economically more powerful country. So Capak, Beros and Bozicevic knew what they were doing just in time.

Italy only has an inflection for the 69th day! Had she instituted drastic measures at least 15 days earlier, her situation would have been significantly different.

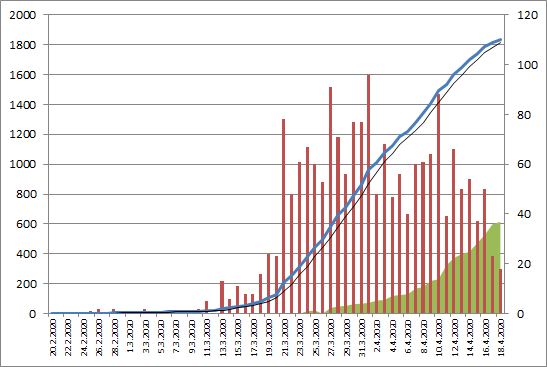

Number of patients in Croatia and trends

OK, this is known to everyone (I guess). The blue line is the total number of registered infected, the black thin line is a trend, the red columns are daily new infected and the green ones are recovered. It is important to know that Beros tells us every day how many recovered in hospitals and how many at home. This is very important. Many countries do not and have any idea how many (registered) patients have recovered at home.

But on the blue curve, it is very important that there are four areas. The first runs until March 21. when the epidemic started the way the epidemic started. From March 31 to April 1 are the results of the first measures to curb the epidemic. From April 1 to April 16 are the results of another set of measures. After April 16, though it is still too few days, something fourth is happening. Look at the slopes of the curve so you will understand.

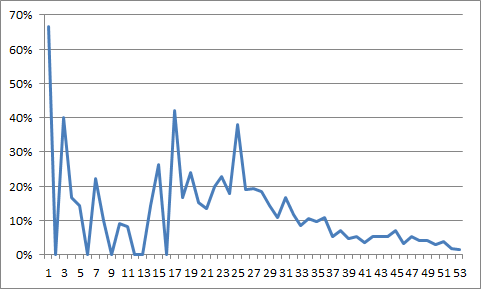

I do not know exactly how the Croatian Institute of Public Health calculates that epidemic spread rate. Here are two ways of looking at it. The first way is looking at how many newly-infected are compared to the “ironed out” total infected. What does “ironing” mean? Croatia is small. A bus from Turkey arrives or a virus enters a home in Split or because of an earthquake we do not process all test swabs that day. But compensate for the next big changes in the curves. That is why I “iron” the curve in two ways, so that such jumps do not significantly affect this coefficient. And here's what I get:

Ratio - how many newborns are compared to a little infested by then

The green curve is important. Not only has it been calm for quite a while (that's when they "leveled" the upper blue curve), but what matters is what has been going on in recent days. For the last six days, this green curve is below one, which means that the spread of infection is decreasing.

But there is one other curve, which is perhaps fairer: the relationship of the newly infected with the currently ill (thus, without recovered)! Here's that one (unironed):

Relationship of newly infected with currently ill (thus, no recovered)

And that's good.

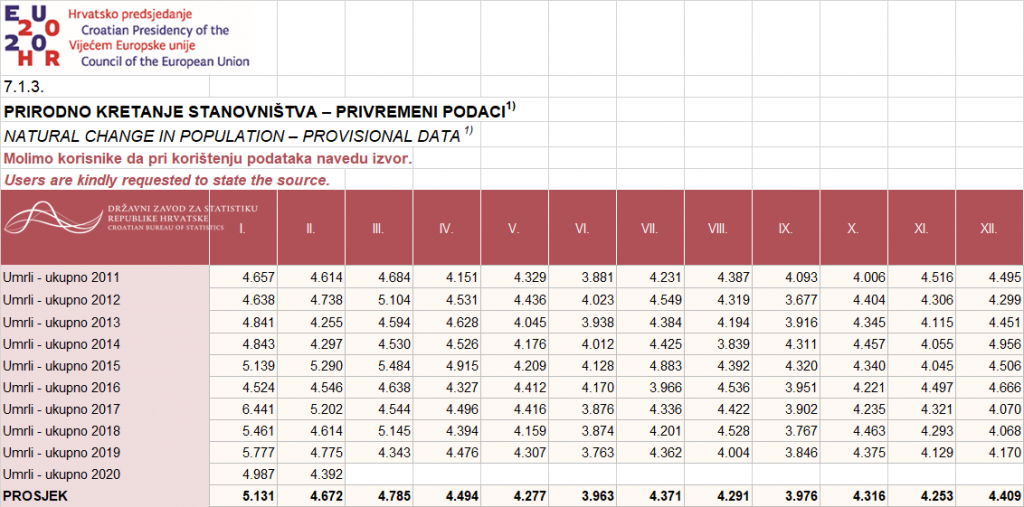

I received more contributions immediately. An excellent graphical representation of the testing ratio per million population and the percentage of positives shows who optimally tests and who does not. If you are about 10% positive you have found a good measure - Croatia is. Something ugly is coming to Brazil, only if the good weather saves them.

Comparison of the number of tests per million and the percentage of positive ones - by Milan Stevanović, April 18

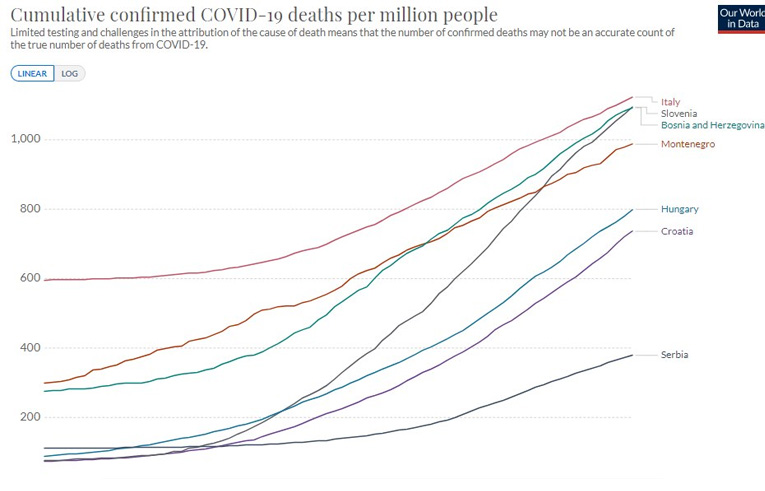

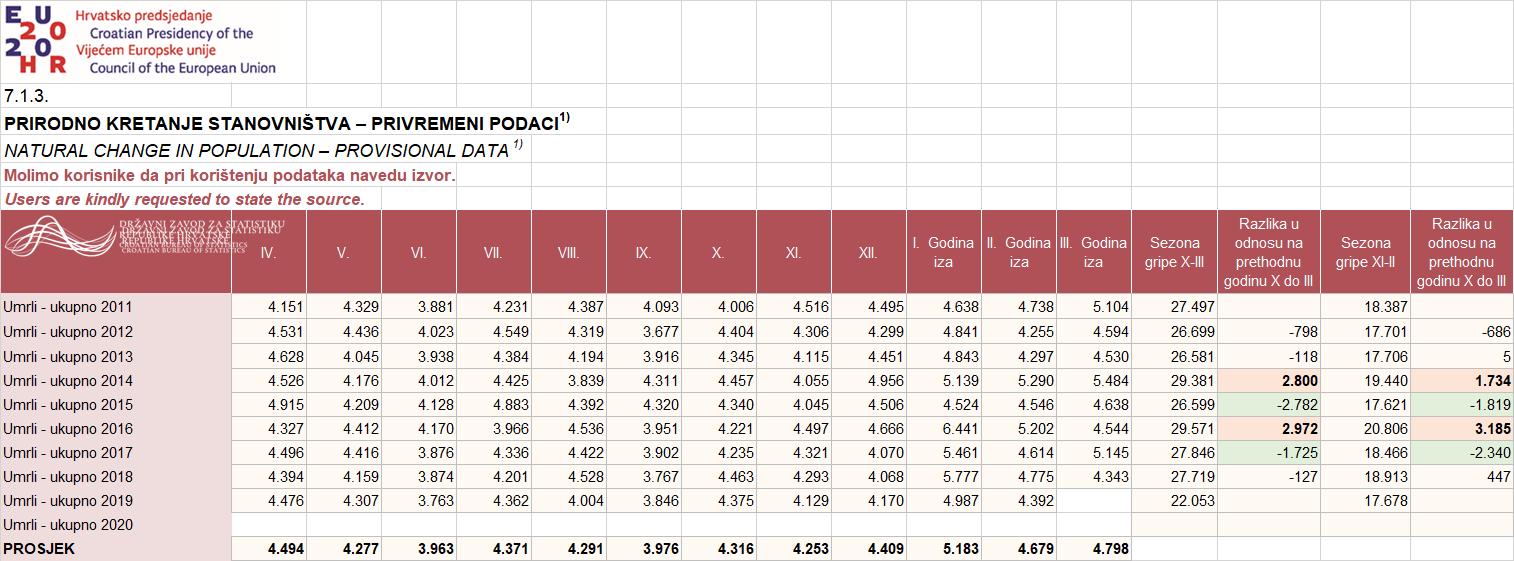

I was also bothered by what Zoran Milanovic told N1: “There are many things for which we have no answers, but we go over them and continue to live. In January 2017, it was calculated that the death toll was 6500 that month. However, a year earlier 4500 people. From what? 2500 people more. There were no car accidents, suicides. Two thousand people have died more than average. It’s a scary figure and we knew it and no one responded. This was probably an epidemic of more severe flu, because in this seasonal prolapse more and more die, and so it is calculated because we do not test for the flu. But when you see that 45 percent more people died in one period than normal in a 10-year average in that month, something happened, we don't know what. "

Some people wanted to interpret it as seeing nothing happens when 2,000 people die from the flu, life doesn't stop. But that's the point - if the measures had not been activated the number of dead would have been at least 2,000 to 4,000 more as they die due to strong flu seasons such as 2014/2015 and 2016/2017 - see the data.

DSZ data on deaths by months

Data on deaths compounded by flu season

If you want to play and check yourself, you can find great visualizations and country comparisons here.

Croatia's 3D Printers Ease Medical Supply Shortage

April 15, 2020 — The coronavirus crisis activated 3D printers across Croatia, with an impromptu unification of about 100 people all around the country providing medical professionals with much-needed supplies, according to Jutarnji List.

Among the more active are Osijek residents, who have printed about five hundred protective visors for medical professionals every week since the crisis began.

The whole initiative started virtually, via a Facebook group.

"We have a group called '3D print experts Croatia,' which is the largest gathering our kind in our country," IT expert Valent Turković told the paper. In addition to making visors, he and a colleague coordinate the collection and distribution of 3D-printed materials to area hospitals.

"The idea started from many directions, from all over Croatia. Medical visors of this kind are a new solution, recently created in the Czech Republic," Turković added.

In accordance with the huge demand for protective medical devices, the Czech company Prusa3D designed the mask and made its schematics public.

"This information immediately came to our group and people started printing, and some even optimized the design," Turković said, adding that Split's University was among the first to start production systematically.

People with 3D printers and enthusiasm for helping began to appear on all sides. Turković said the Facebook group created questionnaires for everyone and then grouped people together by region to bring together those with more and those with less experience.

One or two people were selected in each city to collect masks and deliver them to hospitals.

"Often, people often want to take the mask to the hospital as soon as they print the mask, but for security reasons, it is definitely a recommendation that they contact us from the group and allow us to make the delivery," Turković added.

The biggest challenge for them right now is getting plastic parts for visor masks, that is, films or resistant overhead films.

All the masks they make, he says, go to public health services for free. They receive inquiries from private clinics, which they reject.

The masks protect the whole face and covering the eyes, though doctors still wear surgical masks underneath them.

The solution, doctors said, is much better than plastic glasses, which blur their eyesight and often fog up. Turković the 3D printers cannot keep up with demand.

"We try our best to supply everyone, but we just need time," he said.

The electrical engineering school in Varaždin has designed how to print protective visors for doctors faster and cheaper on 3D printers.

The first model, created by a Czech 3D modeling company, required eight hours of printing for one visor, and the Varaždin residents reduced this to one hour per visor. This also reduced the production cost from HRK 40 apiece to about HRK 25.

Two doctors from Varaždin General Hospital suggested printing the visors when the school took the idea and ran with it.

Overall, the campaign, led largely by the student population, is attended by people from 45 cities with about three hundred 3D printers.

It all started at the FESB in Split and the Student Union of the University of Split got involved, who shared the student invitation on Facebook and the avalanche was triggered. In less than 18 hours after the announcement, 120 students and about a hundred 3D printers joined the action.

Printers have emptied domestic plastic material suppliers. Specifically, a special plastic material used in printing, costing up to HRK 200. Fortunately, all those who have the material who don't have printers donated their supplies and quickly returned production to full capacity.

Croatia's "Relaxed Restrictions" Debate Takes Shape

April 15, 2020 — While some EU member states have begun to open up their economies, Croatia remains quarantined. Despite the growing pressure from businessmen to begin the process of unfreezing the domestic economy as soon as possible, the Government is not giving up a millimeter of its restrictive “policy corona” as of now, according to Jutarnji List.

"There are pressures, we are aware of that," a source within the government told the paper. "However, we will only be able to consider abolishing certain measures and prohibitions when the epidemiological picture permits. So far this is not the case yet."

A process of gradual unwinding began on the European Continent this weekend. Spain allowed almost two million construction and industrial workers to return to work. Italy opened bookstores and children's clothing stores. Denmark opened schools for students. The clearest plan to exit the "corona regime" is implemented by the Austrian government, where all stores up to 400 square meters are open. If there is no significant increase in the number of new infections, they will open all other shops, shopping centers and some services such as hairdressing and beauty salons on May 1.

Does the Croatian Government have at least a preliminary plan for reopening the economy?

"It works on various models, but it's still too early to talk about it. There are no comparisons with Austria," the government source told Jutarnji. "Their curve of the daily number of newcomers has been going down for some time, and here the curve is oscillating.

"The number of new patients has to fall five to ten consecutive days to consider the phasing out of individual measures. While the number of new cases fluctuates between 40 and 70 per day, it is not yet time for that."

It leaves Croatia in the same precarious situation as many other nations — squeezed between keeping a pandemic at bay while also hurting an economy.

"It is important that we be careful when withdrawing the measures," Branko Kolarić, Head of the Public Health Gerontology Department of the NHIF “Dr. Andrija Štampar” told Jutarnji. "The measures are intended to preserve the life and health of people and prevent the collapse of the health system. In addition to physical health, there is also mental and social health. The economy and standard of living are also determinants of health and longevity."

While there is no clear answer from the government on how long the quarantine will last, economists Velimir Šonje said that the economy must be started immediately.

"From an economic perspective, irreparable damage has already occurred and the only economic sense is to start the economy immediately in order to try to return to the point we were in February this year in a year or two," he said. "Now that is still possible, with luck. As time goes by in this isolation, the likelihood of such a happy outcome will be less and less.

"If the Germans calculated that their economy could not withstand more than 11 weeks of such a regime, and we know what the German economy is and what the strength of their measures is, what do you think is the endurance limit for a weak economy like the Croatian one that operates with an indebted country?"

Šonje added it is necessary to open the now-closed section of trade and the service sector "with the necessary modalities to comply with anti-epidemic measures," as soon as possible.

The National Civil Protection Directorate has not said when — or whether — it will extend the restrictions on work and movement set to expire on April 18.

The headquarters passed the largest package of restrictive measures - from the ban on the operation of cafes, restaurants, hairdressers and beauty salons, through cinemas, swimming pools and gyms, until the ban on serving masses and operating a driving school - on March 19, with a 30-day deadline.

"Croatia is too small to recover as a closed economy, whereby I don't just mean tourism because this branch is hit hard anyway," Šonje said. "It is important to monitor data, harmonize measures, and integrate some information systems and protocols in the future because Central European economies are closely linked, and the flow of goods and services, which is vital for all these countries, depends on the people."

Kolarić warned against rushing through reopening the economy. "The world has never stopped this way," he said. "When we have already assessed the threat of this contagion to the global and significantly reduced personal freedoms and so-called a free market, it is important that when withdrawing measures we are careful not to spoil what we have done well."

Croatia's Islands: Few Coronavirus Infections Betray A Dark History

April 6, 2020 — The Bura swung then pummeled the island of Iž along its flank. “Bura de levantara,” as the elderly call it. The air was briny. The seagulls hung suspended in the sky, beaks piercing the wind.

The coronavirus yesterday claimed the life of a middle-aged, otherwise healthy man — the first such victim in Croatia. Yet on this island and many other bucolic, empty hideaways, you’d never know there was a pandemic.

The nation's islands have been spared the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic. Infections remain low, with Murter being the lone exception.

Locals admit their feeling of safety comes with a dose of guilt... and fear that every island's inoculation against this global pandemic is mere luck. Luck which may run out.

“Ne izazivaj vraga,” they say. Don’t tempt the devil. Indeed.

Women of a certain age still say, “Kuga te ubola.”

It loosely translates to “May the plague get you.” Depending on the context, it’s either a curse against an enemy or expression of delighted shock at inappropriate humor.

It’s still in use for a reason. Because Iž and other islands like it suffered terrible losses during previous pandemics. The Bubonic plague, cholera and Spanish Flu swept through these coastal hideaways like a tsunami.

COVID-19 is the outlier — for now.

Familiar with plagues

Virtually every deadly pathogen that hit Europe also swept across Croatia's islands. Anecdotes, church records and census numbers show odd demographic oscillations so precise, they can’t be the usual harbingers of death — war and famine. Process of elimination leaves only disease.

The Bubonic plague hit Zadar 20 times between the sixth and 17th centuries, according to late historian and Iž native Dr. Roman Jelić. The plague became so common, locals built churches, chapels and altars devoted to Saint Rocco, who protected against the illness (Mali Iž’s altar among them).

The island of Lokrum served as a lazaret for Dubrovnik during the Black Death. The innovation quickly spread.

As the plague hit over and over, Zadar’s islands coopted an efficient system of stopping the spread of the illness, one recognizable today and oft-attributed to Dubrovnik. Good ideas, like plagues, often spread quickly.

Confirmed infections on islands went to lazarettos, or infirmaries, built in the hinterlands or the uninhabited islets. This early form of the quarantine and forced self-isolation set the foundations for the current fight against COVID-19.

Still, the numbers were staggering.

The island of Ugljan at the end of 17th century lost nearly 10 percent of its population in a single year. Records suggest the plague swept through the island, end-to-end, with the neighboring islands Galevac and Ošljak serving as lazarettos for the ill.

A century later, Molat lost 141 residents — more than a quarter of its population — in the four years between 1772 and 1776.

Medieval medicine at the time included some isolation measures, but hygiene and knowledge of microscopic killers were non-existent. The islanders of lore were helpless to stop the viruses. A full-time medical professional on a Dalmatian island is a modern invention, arriving about the same time as electricity.

Other deadly pathogens followed the plague: diphtheria, smallpox, scarlet fever, typhus, dysentery, and the Spanish Influenza. The lazarettos built for Black Death sufferers remained, repurposed for every new disease.

No one to infect

The modern coronavirus pandemic in Croatia began around in the beginning of March. Not that anyone on the islands noticed a difference.

The newer houses built by foreigners sat dormant — as usual. The other homes grow quiet, one by one, every time the death bell tolls.

The coronavirus’s great gift to Dalmatian islanders was its timing. It arrived during the annual stretch of ghoulish emptiness that leaves one wondering if anyone lives here at all. Had it hit two months earlier or later — New Years or the summer — and the situation would look bleaker.

The few who live here all year emerge from their homes every morning. Some split olive wood to prepare stoves for the single match that’ll heat their house at sunset. Others wait in line for a loaf of bread.

All have routines to survive early March: the temperature fluctuations and bitter wind sweeping down from the Velebit Mountain make it a torturous time. That signature March Bura. The “healthy” wind which pseudo-scientists around here claim is a panacea for many ailments.

It clears humidity out of the air, they say. Dries the sinuses, leaves a crust of salt on doors and windows. It cuts through the thickest of jackets.

Winter life will keep us safe, they say. Here, the winter sun is medicinal. (From April onwards, it’s a menace.)

Social isolation doesn’t need a mandate here either. At this time of year, it’s the norm.

If COVID-19 found its way to islands like Iž, it’d lack hosts. The regulars on the island keep a safe distance from each other — blame water-saving over hygiene, emotional suppression, and the disinterest that comes with seeing the same faces at the same time every day. Attempts at physical contact betray a too many drinks… or fair-weather friend trying to make good with the locals. We know better.

When a biting wind sweeps across your face and sends a chill to the base of your skull, a hug or a handshake feels ridiculous. Head nods and grunts are enough.

No well-wishers, family members, weekend visitors, or preparations for summer flings. Save a weekend bacchanal for carnevale, or perhaps a funeral, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone visiting Iž or any of the other smaller islands before Easter.

Still Following Protocols

Make no mistake: people here follow the rules with aplomb. The store only allows one patron at a time, each greeted with a squirt of hand sanitizer at the door. The others wait outside in a haphazard line, with each new arrival pointing a questioning finger to see who’s ahead of them.

This rationing and pseudo-caution that comes with assuming everyone is a vector for a virus is familiar. The history of population-wide illness left a mark on many island norms.

In a long enough conversation, someone will mention a distant ancestor known to have died of… something. Those tales still circulate, along with the centuries-old quack medicine for combatting the illnesses.

Locals also used to fumigate their houses with burning juniper bushes to oust the plague. While nobody smokes themselves out of their own home, islanders still have an immeasurable fear of drafts — a well-documented phenomenon that dates back to the era when tuberculosis, common colds and pneumonia were death sentences.

It’s still customary for a visitor to shout your name a few steps before they arrive at your door — a bit of common courtesy predating doorbells but also a chance to be sent away without getting too close.

Folk medicine remedies are still common. Every bodul (islander) shoveling spoonfuls of honey into their gullet to combat a cough can thank their ancestors, who did the same to survive tuberculosis and pneumonia. Ditto to inhaling the vapors from sage or chamomile tea, a centuries-old remedy for pulmonary illnesses.

Some islanders even continue to pile on layers of clothing and blankets to treat a fever, believing it helps the body cook out the pathogen. These treatments are still being suggested to young islanders with the fervency of Gospel.

Perhaps the closest the islands saw to today’s pandemic was the cholera outbreak of 1855, which hit every settlement on every island in the Zadar archipelago. The incomplete records from the time show 7,770 people were infected, 2,690 of them died. A 34 percent mortality rate. (It should be noted Patient Zero arrived from Italy.)

The author's home: devoid of people whether there's a pandemic or not.

Offering An Escape

During past the pandemics, those fearing death often fled to the Dalmatian islands. It may happen again.

Already detached from societal epicenters, the potential for an island becoming a pandemic hotbed disappeared over the last century, as islanders emigrated to the generous shores of Canada, Australia and the United States. Even Murter, now a hotbed, had its COVID-19 allegedly imported by tourists who wanted to get an early start on "The Season."

That's not to say the islands like Iž and others are immune to nasty pathogens and the ornery nature of life on this planet. But maybe the four-mile gap between these shores and the mainland is just enough to keep the inhabitants safe.

That sense of detachment and self-sufficiency fuels the people living here year round. But the longer this pandemic lasts, the supposed-faults of island life will slowly become appealing to The Crowd. Those who often shun a quiet existence to be at the vibrating center of modern civilized life. Their norms are now poisoned.

Isolation, solitude, peace, and detachment from the throngs, shopping centers, cultural institutions and a quiet social life... are now luxuries. And potential life-savers.

A parade of fresh faces uprooting their homes to these islands is inevitable. They’ve already made calls, promising to be here soon. They’ll join a long and storied tradition: escaping to the Dalmatian islands for refuge.

It’s something those of us with roots here all share: there is no native bodul. Everyone came here to escape from something: fights between Venetians and Ottoman Turks, famine… plagues.

This pandemic will end. The sun will continue to rise just behind the neighboring island of Ugljan and settle in the west behind the church steeple at the top of the hill. Like it always does.

Those still alive when this is all over will tell their kids and grandkids what it was like to watch fraction of the world suffer even though the illness touched nearly everyone.

And those who passed the time on Croatia’s bucolic little islands will hopefully shrug and say, “Nothing really changed for us. A few more people showed up and, when it was over, they all left.”

Don't tempt the devil.

Croatia's Entrepreneurs Use Guile, Luck To Fight 'Coronavirus Economy'

April 4, 2020 — Runner, entrepreneur and tourism innovator Berislav Sokač saw the early warning signs when governments called off punishing 24-mile races.

“Oh, I knew when things were going to be bad… when the Tokyo Marathon was canceled,” he said.

The founder and head of Run Croatia, a platform focused on sports tourism, is used to the pain-gain logic which binds suffering and improvement. He is, after all, one of the country’s most-accomplished runners.

But his Zagreb-based business hasn’t encountered a challenge like COVID-19. The ban on public gatherings and large groups put the kibosh on all scheduled events and runs. More than a cough and fever, the virus cut the legs off the nation’s largest running platform.

It puts Sokač and many other members of the Glas Poduzetnika (Voice of Entrepreneurs) in the unenviable position of trying to keep their companies afloat with zero revenue. The organization of small business owners, artisans and self-employed emerged in March to advocate economic measures meant to ease the pandemic's effect on entrepreneurs.

Business owners in a series of interviews with Total Croatia News expressed a mix of uncertainty, grit and hope in the face of fluctuating conditions. Despite a daily drumbeat of new infections and deaths.

For some, vital agreements fell through, reverting them to a one-man-show operation. Others shut down operations, kept workers on the payroll and are negotiating with landlords and creditors.

They, like Sokač and many others, expect pain with no promise of gain.

They welcome early interventions by the government and hope for further action. Quick thinking and a bit of luck have them predicting survival and even long-term renewal — whenever this grim period ends.

Inadvertently prepping for government help

Orlando Lopac ordered equipment for his fitness company, but it ran late at the end of February.

The founder and owner of Zagreb’s ubiquitous Orlando Fitness Group knew delayed shipments from US-based companies often betray a bigger problem in the production chain. A few phone calls to suppliers in Taiwan and talks with colleagues in Italy confirmed the worst.

“That’s when I understood the seriousness of the whole situation,” the 48-year-old said.

The equipment at Orlando Fitness now sits untouched.

The ensuing weeks included whirlwind preparations, all-hands meetings and planning: provisions made in case of forced closures; financial plans drawn if clients couldn’t go to one of OrlandoFit’s three Zagreb locations.

Communications strategies — bulletins, social media posts, emails — drafted in late-night writing sessions, laying out in plain language how memberships would be prorated to a later date.

“We always tried to be three days ahead of the virus,” Lopac said. “People have put a lot of trust in us.”

Then, on March 19, the government ground public life to a halt, closing all businesses that didn’t sell food or medication.

Lopac’s fitness centers would be dormant indefinitely.

The prepared social media posts and emails were met with understanding by customers.

Lopac and his crisis team laid out a financial strategy to keep the company’s employees on the books. It called for painful cuts in wages. Then, an all-hands meeting to break the news.

“We told them what’s coming is very hard,” Lopac said. “We told them our cash flow would dry up.”

Byzantine bureaucratic labor rules meant just one worker’s dissent would topple the plan, setting off a daisy chain of ugliness which would kill the company.

His 30 full-time employees would need to annex their contracts and become minimum wage workers. Then, stay at home and hope the pandemic wouldn’t last longer than the two months-worth of salaries the company could cover.

Lopac spent more than an hour presenting the plan to his workers, explaining the maths and answering their questions.

“Because we made the presentation face-to-face, and spoke directly and took the time to answer questions, they all accepted,” Lopac said. “If I sent it all in a long email, I wouldn’t have a company right now.”

Then, a stroke of luck.

The Croatian government on April 2 unveiled a second set of economic measures designed to prevent massive private sector layoffs.

Prime Minister Andrej Plenković said all minimum wage employees’ salaries would be covered, while raising the minimum to 4,000 HRK. The plan also added three months of tax breaks for qualifying businesses.

Lopac’s two-month lifeline and pay cut became a great idea.

Business owners greeted the government’s measures with open arms. Labor Minister Josip Aladrović said within days 69 employers signed up, keeping over 410,000 employees on their books for March.

Most applicants were from the catering and service industries, Aladrović added, reflecting the 53 percent drop in overnight stays last month. The nationwide shutdown of hospitality businesses also forced a 90 percent drop in turnover in the industry at the end of March. Croatia was emptying.

The measures offered some leeway for the marathon runner Sokač and fitness guru Lopac. Both will use them to their full advantage.

“It wasn’t easy giving someone pay while they sit at home and do nothing,” Lopac said.

By reducing employees’s compensation to minimum wage, they avoided layoffs. With the Croatian government covering wages, they can shift that loss off their books.

“Now, we aren’t saddled with any large expenses and production costs,” Sokač said.

Equally important for both, they feel the small business community became the fulcrum of public policy at the national level for the first time.

“The government was ready to listen,” Sokač said. “The entrepreneurial establishment was heard. That’s a lot of small gears holding up the economy.”

Lopac expressed a more befuddled view.

“What angers me the most… were we really supposed to come to a pandemic to get to a normal level of communication between the government and entrepreneurs?” he asked. “Did it have to come to this?”

Guessing government’s next pool of measures has become a favorite parlor game for economic watchers and business owners.

Some belt-tightening already began this week.

Plenković put a moratorium on new public sector hires within his government. He also froze the second search to buy fighter jets.

Even the seemingly recession-proof local Croatian public sector experienced cutbacks. City administration employees in the City of Pag, for example, will see 20 percent pay cuts. Ditto workers at city-owned companies.

What’s left to cut? Many eye the mandatory fees charged to business owners every month — forests, water, radio and television frequencies, among others. Early rumors suggested the government would scuttle the levies. They remain for now.

How bad can it get?

Events around Europe and rest of the world develop the contacts and stories his bundle of media companies churns out at a substantial clip. The gatherings are all on hold or canceled outright — as Tomić expected.

“Those who understood anything about virology knew that the virus would leave China,” he said.

Worse than the conventions, the photography and video gigs garnering additional revenue have all fallen through, leaving an immeasurable hole in his company’s finances.

“If someone asks me what’s my revenue now, I have no idea,” he said. “Some jobs were already agreed upon. Some were in the works. Some are renewed every year. Some were a head nod and promise to get something done. They’re all on hold now.”

For Sokač, Run Croatia’s numbers are grim. He forecasts a 70 percent drop in revenues this quarter, and a 40 percent drop if the crisis lasts into autumn.

A blow to the tourism industry would be devastating. He pointed to a race organized in Novalja, where 70 percent of registered runners would come from outside the country. Closed borders would leave him reliant on the 30 percent of Croatian participants — if they show up.

A continued moratorium on public gatherings would cancel the race — a 100 percent loss.

“Worst case scenario, we’re looking at an 80-90 percent drop,” Sokač said.

Holding onto employees

Tomić’s company relies heavily on him, one full-time employee and eight others working in a freelance capacity.

That circle is tightening.

“I have a small firm,” he said. Halting isn’t an option. “In this company, a lot of things rely on me. I either work or I don’t work.”

He doesn’t expect layoffs.

Sokač first reached out to the social media influencers and people he outsources to, telling them the races earning them money may be canceled. Then came the “crisis meeting” with employees, a common response with nearly all the business owners interviewed.

He told his workers they’d weather the pandemic using whatever measures were available, keeping Run Croatia alive in some iteration.

“I’m not prone to panic,” Sokač said, adding his employees share his demeanor. “I’m lucky that the people who work for us also live for what we do.”

He knew the run-friendly business would likely fall off significantly. Luckily, he created an alternative stream of revenue.

Smart Planning and a Dash of Luck

On Jan. 15, Sokač added another wing to the Run Croatia ecosystem he’s built since founding the company in 2015.

“It’s important to create a platform. The stronger the platform, the higher your immunity to crisis,” he said.

That addition was a web shop — exactly the sort of operation exempt from the restrictions put in place to fight the pandemic. Traffic to the site jumped in March, as soon as people were told to stay at home.

Suddenly, Run Croatia had a lifeline.

“It was totally by accident,” Sokač admitted.

Lopac said now that wages are off his mind for the short term, he’s trying to renegotiate deals with his financiers and landlords, using the same transparent approach he took with his employees. Early signs show promise.

“The things I am not doing: complaining, crying and waiting with hands outstretched looking for help,” he said.

But just in case, Lopac spent the better part of last week developing a promising alternative revenue model — one he’s keeping to himself.

“At this moment, OrlandoFit will be alive as long as I can keep working at the same tempo,” he said. “This will survive the same way it has over the last 30 years.”

Sometimes, the nature of the business works in one’s favor, according to the journalist Tomić.

“It’ll be hard to survive the next few months,” he said. “Thankfully, this journalism bit has strict controls on expenditures.”

The low overhead and high amount of news means Tomić’s “stay at home” lifestyle remains uptempo. He admitted to sometimes hammering away close to 17 hours a day.

“At this moment, the volume of available content hasn’t been greater,” Tomić said joylessly.

Looking Ahead with Hope

Tomić knows that this pandemic, like most calamities, will pass. The real challenge, he said, will be the recovery. A wrong turn or lackadaisical response could lead to “an economic death spiral.”

“When we come back, it can’t be at 90 percent. Or 100 percent,” he said. “It has to be at 150 percent.”

Lopac’s forecast for his company is somber: between two and three years to be back at full force. He admits fitness centers grow quiet during summer months. Many members disappear until autumn.

The bigger problem is the economic aftermath. A downturn leaves people clutching their wallets. Luxuries like personal trainers and fitness center memberships are among the first expenses discarded.

There’s also the nagging caricature of gyms as dens of bacteria and sweat.

“I know our fitness centers have the highest level of hygiene you can image,” Lopac said, spelling out the protocols and culture of cleanliness at his gyms. “I can tell you it’s cleaner than any grocery store. But the perception and thinking of the public might be different.”

Sokač, the marathon runner, admits to being an optimist. His kids, he said, are a testament to the positives this coronavirus has wrought.

“I see on this digital schooling a lot of attention is being given to physical fitness,” he said, pointing to new online courses and curriculum. “These are all changes we can keep.”

The pandemic? It’s just another challenge.

“You have people who are negative and depressive and they can’t function,” the 45-year-old said. “No matter how hard things get, you have to find something that works."

Korona & Corona: Eponymous Virus Doesn't Stop Tiny Croatian Village

April 4, 2020 — Idyllic scenes of the picturesque Istrian hills, the waking nature, and the chirping of birds on a sunny day, and in the middle of it all - Korona. No, not the virus that has changed our lives from the ground up these days, but a village. Reporters from 24sata visited the enclave on a hill between Motovun and Buzet, home to only five people.

Life in this small Istrian village continues unabated, while the world around it toils and struggles with a pandemic. Its only tie to the virus, fortunately, is its name.

"Get out of here, don't come near me, move on," an elderly woman Marija warned the journalists with a smile, sweeping the yard and appreciating the sizable distance between herself and the visitors.

Marija, one of five residents, lives alone in her house. Her son's house is close by, with three of them living there. The reporters knocked on the door for them too, but there was no one there. Marija says they’re all busy planting potatoes.

Not dropping the broom, she shows crates full of small potatoes for planting. These are, she says, the ones you don’t need to cut. They go to the ground.

Asked if she fears the coronavius that threatens everyone.

“We have nothing to fear, there will be a story to tell,” she replied. “I’m not going anywhere. Where can I'll go?”

Marija’s age and stature suggest she’s seen a bit of the world and experienced life’s highs and lows. “It's good while we have something to eat, that's why we in the countryside work all the time. She complains that the virus has the same name as the village she married into and has lived in from an early age.

She is old, she says, and has to die of something, by grace or force, and that coronavirus is the least of her problems compared to anything she has gone through in her life.

Born during the reign of Italy, she felt what war, hunger and poverty were like. She had been married for sixty years, now a widow. Pressed for her age, she keeps telling the reporters she’s 100, then letting out a laugh.

"They to laugh better than to cry,” she said, as the reporters went on to her neighbor Milka.

She warns the reporters not to come closer than a few meters. Milka lives alone, but lively farm work hummed all around her. Milka’s son-in-law just arrived, and with his plow he prepared the ground.

"We've been fighting the corona as long as we’ve been here, and we're still alive," he yells, laughing. Milka says she has a real son-in-law, and she wouldn’t trade him for anything.

These days there are few who come to Korona, and Milka likes it that way.

"I'm afraid and staying at home,” she says. “I’m not going anywhere, and my legs are hurting, too," adding it's better to be alone while all this is going on.

They have enough to survive, Milka said. They struggle and work because, as she herself says, "if you don't do it, there is nothing."

Beroš to Young Dalmatians: Stay the F at Home

April 3, 2020 —Croatia’s Civil Protection Directorate earned kudos for its response to the coronavirus crisis and strict measures seemingly followed by everyone — except, apparently, Dalmatians.

The Civil Protection Directorate wanted to deliver positive news, with 48 new infections showing a steep in the virus’s spread yesterday. Instead, Health Minister Vili Beroš and other officials chastised young folks in Croatia’s coastal region for reportedly flouting social distancing measures and restrictions on movement. Data released by Google later in the day confirmed not just Dalmatians, but Croats in general are flouting the rules.

Locals and officials claim many young adults in Zadar, Split and Šibenik continue to congregate in cafes with tinted windows, drinking and socializing. Footage also emerged of Split locals enjoying a casual game of their traditional take on volleyball.

Various reports from around the country suggest social distancing and self-isolation measure have met their match in Dalmatia’s traditional contrarian spirit and self-assurance.

“This is not acceptable behavior,” a visibly irate Beroš said during a press conference yesterday. “In doing so, they endanger themselves, their families and the health of the nation. I would like to tell everyone to be patient and wait for this epidemic to end. There will be time to socialize and relax. Until then, we must be disciplined and extremely cautious.”

Zadar’s Mayor Branko Dukić, a medical doctor himself, is baffled.

“I understand everyone who has a hard time being indoors, I have not spent as much time in my entire life as I have in recent weeks,” he reportedly said in a statement. “But I cannot understand that we are playing so easily with the health and lives of ourselves and our loved ones. Whichever state and whatever city tried the ‘it won’t happen to me’ tactic ended in disaster.”

As the directorate was holding its press conference, locals in Split publicly defied orders to stay at home by continuing to play “picigin,” a local beach-volleyball variant that favors banana hammocks and shallow water.

One day later, police promised to put the kibosh on all games of “picigin.”

“Had police officers found themselves at the ‘picigin’ game, they would have certainly warned the participants to disperse. You can walk, but ‘picigin’ cannot be played under these circumstances,” Split police reportedly said in a statement.

Workers in Dalmatian hospitals took to chastising their neighbors as well. One sent a plea to Dalmacija Danas, with a video of his hospital ward.

“Do you want me to send footage of a man choking and begging to be intubated?” he wrote. “Or are you waiting for the next one to be one of you ?! Hello?! Are we going to do anything?!”

Stipe Čogelja, Head of the Department for Tourism and Maritime Affairs of the Split-Dalmatia County, said in an interview some locals are exploiting the situation to build illegal piers and other structures on the maritime commons, a protected strip of land where the sea meets soil with strict limits on construction.

The head of the Civil Protection Directorate and Interior Ministry Davor Božinović said he won’t introduce stricter police measures or regular patrols, as some neighboring countries have.

“I did not know about young people gathering in cafes, but it does not surprise me,” he said, adding local police forces will be instructed to monitor local cafes and bars. “Young people are often unaware of this and when they do not see and feel that there is an enemy that we all fight together, they think that it is not there.”

Director of the Infectious Diseases Clinic "Dr. Fran Mihaljevic” Alemka Markotic also denounced the relaxed attitude, pointing to the growing number of patients on ventilators. New figures from the United States and other western countries offer a grim forecast for any critically-ill patient requiring a breathing machine, with a majority dying anyway.

Markotić said it’s best to limit any situation that might spread the virus.

“I am sure that Split may be the first in everything, but that it does not want to be the first in the corona,” she said. “Please show the citizens in the south that you are better than others and do not allow the corona to expand.”

The chastising runs against the overall compliance shown by Croats around the country — something reiterated with a trove of data showing Croats have cut back on their movement significantly.

The online giant released a trove of data showing users’ movement during restrictive measures in comparison, showing Croats cut back their outdoors excursions by some 82 percent from Feb. 26 to March 29, compared to Jan. 3 and Feb. 6, before restrictions took force.

Google users cut back their trips to work by 50 percent across the country, while people are overall spending 16 percent more time in residential areas.

But the most telling statistic: visits to parks, which in an era of “stay at home” should be close to zero. Overall, Zagreb County, Varaždin County and Lika saw the biggest drop in visits to the park.

Dalmatians didn’t follow suit. Residents of Šibenik-Knin County curtailed their visits to parks by only 12 percent. Not far behind were Osijek, Karlovac, then Zadar.

Croatian Public Health Institute Director Krunoslav Capak criticized the reports from Split and Zadar, warning the consequences of their nonchalance would come back to haunt them.

“Today, there are half as many new cases as yesterday, which is an extremely favorable situation and we want this trend to continue,” he said at the press conference.

Coronavirus in Croatia Has an Added Symptom: Social Stigma

April 2, 2020 — The coronavirus often causes spikes in body temperature and a prolonged, dry cough. It also leaves some patients with a social stigma that’s hard to shake in the midst of a pandemic.

Complaints of lost jobs, finger-pointing and passive-aggressive condemnation are common, making an already-difficult situation worse, according to various reports.

Nenad Katić, 40, his wife Ivana, 38, and their son and daughter all have tested positive for COVID-19. The Nincevići residents remain in isolation at home, while Katić’s mother is in hospital. They claim they’ve been ostracized by neighbors and blamed for the virus’s rapid spread within the village.

While Katić cannot pinpoint where exactly they were infected, he suspects a mass on March 19 for the feast of St. Joseph, held in violation a prohibition on public gatherings.

“No one speaks about this mass in public, as if it was not even held and as if the church was not nearly full,” Katić told Slobodna Dalmacija. Instead, he says locals have labeled his currently-hospitalized mother Finka as “patient zero.”

Even the local priest, Ante Matesan, reportedly told another news portal that the infection was transmitted by a parishioner who helped clean the church — alluding to Katić’s mother, who volunteered to tidy up along with other parishioners.

The town now has an outsized number of confirmed cases, mostly people who attended the mass.

“Some members of the church congregation were infected. The faithful who were in the church were also in mortal fear, yet only the story of us spread,” Katić told the paper. “We were neither at mass nor did we transmit the coronavirus; we most likely received it from my mother.”

Father Matesan told Slobodna Dalmacija he had a fever lasting over a week, and was awaiting test results. He claims he did not know about the ban on public gatherings and did not wish ill upon the Katić family.

A new scarlet letter

Others have seen news a positive spread almost as quickly as the virus itself.

A list of COVID-19 test results began circulating the island of Murter, the only locale in the country to be in full quarantine, according to ŠibenikIN. Sources told the news site a full list of those tested, along with their results, circulated the small island via text message. It was later confirmed by local police.

ŠibenikIN’s source reportedly found out he had coronavirus via the list — not a medical professional.

“The names were […] sent all over the place and all over the island, possibly even further, which is a violation of the right to privacy and the right to confidentiality of patients' data,” the source said. “This is something really disturbing from a moral point of view; that the entire village will know before the families of those tested as well as the patients; that it must be known who are ‘the infected' them in order to stigmatize them.”

Testy Reactions

Some have a hard time getting tested at all. After they do, treating the symptoms becomes just one of a growing list of problems.

Goran Radulović had a random selection of COVID-19 symptoms: the telltale cough and a mild fever barely crossing the 37℃ threshold. He called all the prerequisite numbers: the epidemiologists and Croatia’s coronavirus dedicated number. No luck.

He went to the Infectious Disease Clinic Dr. Fran Mihaljević, the clinical heart of the nation’s coronavirus response, only to be sent home, he told Vecernji List. He was told his symptoms didn’t merit testing; to call his doctor.

“Ninety-nine percent of people would give up seeking further medical help,” he told the paper. “Thanks to my neighbor, I was able to [get a] test at half past ten in the evening.” The results the next morning came back positive for COVID-19.

Later testing showed his wife and two children were infected as well. The kids are asymptomatic, Radulović said, and his wife has a mild case, with only one feverish day.

Radulović can’t say for sure where he was infected. There were no skiing trips. No family members who were abroad.

The reaction of some neighbors and acquaintances hit as hard as the virus itself. Some asked if they can help. Others called Radulović and his family “irresponsible” and worried they would infect others. One neighbor, he said, even asked for a copy of his positive test results to include in a request for sick leave.

The illness itself, he said, is bad enough. “The cough is deadly, something indescribable.”

As the virus progressed, the asthmatic Radulovic grew worried and called emergency services. He hoped for a lung x-ray at the hospital and perhaps some oxygen. He ended up in a tent in a parking lot and was told to sit on a bench.

“While I was waiting, a hundred people passed by,” he said. “Some were certainly negative, but after their stay there it was very possible to ‘collect’ the virus.”

Doctors measured Radulović’s blood’s oxygen saturation and pulse and told him within an hour that he had no need for hospital treatment, he said. Given Radulović’s asthma, doctor’s suggested he call an ambulance if he began feeling shortness of breath or choking.

All that was bad enough. Then Radulović and his wife were both laid off. She a hairdresser, he a driver for ride-sharing services like Uber and Bolt. Tenants, their landlord has extended their stay — but that’ll only last for so long.

“So if you get sick, no one cares and you're left alone,” Radulović said. “I do not know what would happen to my wife and me, would anyone in this society care for our children?”

Judge: Croatia's Coronavirus Response Violates Constitution

March 31, 2020 — The Croatian government’s response to the coronavirus outbreak includes several violations of constitutional rights, according to Judge Andrej Abramović, who sits on the nation’s top court, according to Jutarnji List.

The judge claims the National Crisis Directorate did not have the legal right to limit citizens’ movement, forcing them to stay place in their legal residences. The Law on the Civil Protection System, as well as its amendment adopted by Parliament on March 18, did not give such authority to the National Directorate, he argues.

Abramović presented his arguments in “Constitutionality in the Age of Virus,” on iusinfo.hr.

Measures to combat the spread of coronaviruses are necessary but should deployed using existing procedures and laws in the Croatian constitution, the judge writes. An amendment to the Civil Protection System Act cannot delegate to the Civil Protection Directorate the powers of all government bodies because it means the suspension of democracy, the de facto dictatorship.

Abramović argues that the purpose of his text is not to polemicize the measures that are being taken but "to warn who is taking them,” arguing bypassing the constitution could cost “those values that are even more important than human lives in a democratic society."

Abramovic, in the published text, also argues against the way the island of Muter was put into quarantine. The decision was made on March 25 by the Civil Protection Staff of Šibenik-Knin County.

"Physical barriers were put on the access roads. Like during the war,” the judge writes, warning that the decision is illegal on several levels.

According to the Law on the Protection of the People from Infectious Diseases, quarantine, according to the judge, can only be forcibly accommodated individuals, not entire areas. In addition, the quarantine can be determined only by the Minister of Health. Also, those forcibly placed in quarantine are due compensation, he adds.

"None of the above," Abramović points out, "is the case here. If necessary, [the measures] must first be provided for by law and then introduced in the manner prescribed by law. This is how residents are at the mercy of activism of some kind of directorate."

The Constitutional Court judge also discusses the way in which the authorities determine the measure of self-isolation defined by the Law on Infectious Diseases Treatment as "isolation and treatment in the apartment".

It is quite questionable to the judge whether one's constitutional rights can be restricted when it is beyond doubt that there is a test that confirms or denies infection.

"Detaining people in their own homes without testing puts them in a precarious position: neither healthy nor sick, they are stigmatized to the extent of being threatened by most."

By problematizing the way in which the concrete measures were enacted, Abramović seeks to draw attention to the essential constitutional issues raised by the COVID-19 pandemic and the measures taken by the authorities to suppress it.

In his article, he raises doubts that the ruling majority in Parliament deliberately avoids applying constitutional and legal norms, in order to allow itself to manage the crisis by means of laws passed by a simple instead of a two-thirds majority.

He analyzes the maneuver that the governing have resorted to in order to avoid the automatic activation of Article 17 of the Constitution relating to emergency situations, whose activation of all decisions affecting constitutional human rights would have to be approved by the Parliament by a two-thirds majority, as long as that legislative body can meet.

Abramovic clarifies the amendments to the Civil Protection System Act that was passed by Parliament on March 18, introducing the concept of "occurrence of special circumstances" even though the description of "special circumstances" is identical in substance to the state of "catastrophe" that the law already contains. "Why did the government not declare the disaster foreseen by law?”

Abramovic suspects that by this maneuver, the government sought to avoid the obligation to seek a two-thirds endorsement of the parliament for measures that encroach on constitutional human rights.

Abramović also chastised his fellow constitutional judges. “The Constitutional Court systematically, using lack of an explicit constitutional norm, refuses to participate in interpreting the Constitution in the a time of crisis, insists on deciding post-festum, when the eventual determination of the disproportionality of the measures taken will no longer mean anything to anyone."

The judge says that as a layman he does not know, nor does he dare to predict, what the consequences of such treatment will be to combat the pandemic. But the consequences will be bad in relation to guaranteed human rights - he is quite sure of that.

"There is no such necessity that justifies acting beyond the laws and the Constitution because both the Constitution and the laws regulate the state of emergency,” he wrote. “In the long run, the damage to democracy is greater than the damage caused by any virus. "

There is no doubt for this constitutional judge that Croatia is in a state of emergency as defined in Article 17 of the Constitution. "Where will you find a greater state of emergency than the global pandemic, the cessation of human and commodity circulation, quarantine and isolation of all kinds and every step of the way?”

Abramovic points out that it is frighteningly widespread that Parliament is no longer acting in the event of a state of emergency. "This is a wrong assumption,” he explains. Article 1 of the constitution states that it does not act only if it cannot meet. "Such a false perspective that the Parliament is not functioning in a state of emergency offers the wrong answer: if the legislature is no longer Parliament, then it will be someone else, possibly also a body that manages the crisis on behalf of the Government. And then it is a coup.”

Coronavirus to Cost Thousands of Jobs, Steep Drops in Wages

March 31, 2020 — The coronavirus’s first non-medical victims are 8,000 workers facing unemployment, as well as 300,000 others facing steep paycuts down to minimum wage, according to Vecernji List.

The stark The Tax Administration yesterday said it received 39,047 requests from companies and craftsmen to delay their payment of taxes; one-third of the requests came from the hotel and catering industry.

In addition to companies and entrepreneurs who are banned from working, others with a drop in income of more than 20 percent, including the self-employed can count on government assistance in paying wages.

Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovic’s government met on Monday to create a new package of measures to alleviate the problems of entrepreneurs during the coronavirus epidemic. The measures reportedly include a freeze on administrative fees and compulsory contributions to the Ministry of Economy. Officials expect the plan will be adopted this week.

Under the proposal, oft-lamented fees would not be charged over the next three months, with an option to extend the measures if necessary. The cutback on compulsory payments would also include government fees for water usage, radio frequencies, and membership fees for the Croatian National Tourism Board, among others.

Sources told Vecernji some fee cancellations experienced headwinds, particularly the compulsory charge for Croatian Radio Television (HRT) service.

The Economic Ministry says some of the benefits now being discussed will be permanently abolished, in line with the plans for administrative relief already in the works before the crisis.

There are also rumors from Brussels that the minimum support given by the European Commission will be raised from the current €200,000 will be raised to €1 million.

In the two weeks of isolation, the number of unemployed citizens registered with the Employment Service increased by more than 6,000, but also information that three thousand workers had found a job. The fees cancellations would come as many small businesses worry for their future.

Croatia has approximately 100,000 active legal entities and about 80 thousand craftsmen. Already in the first week of implementation of the coronavirus measures, every fourth craftsman and every fifth company requested a tax deferral.

The hospitality and tourism sector had 12,804 requests, the most of any. More than 800 entrepreneurs from the health and social care systems, 762 from information and communication activities, and 639 from real estate businesses are also seeking a delay.

There is a lot of focus on public sector salaries as well. The Institute for Public Finance calculated that reducing public sector salaries would do more harm than good at the moment.

Cutting the salaries of employees in institutions and companies where the government is the predominant employer would bring relatively modest savings of 0.38 to 1.22 percent of GDP annually, while the negative consequences would be much greater.

The negatives include a fall in citizens' living standards, a fall in spending, a loss of staff, the collapse of public institutions, and an even greater decline in GDP. However, the authors of the analysis do not dispute that, when the crisis is over, public sector wage cuts will eventually come to a head.