Analysis: Coronavirus in Croatia Compared to Other European Countries — April 21 Update

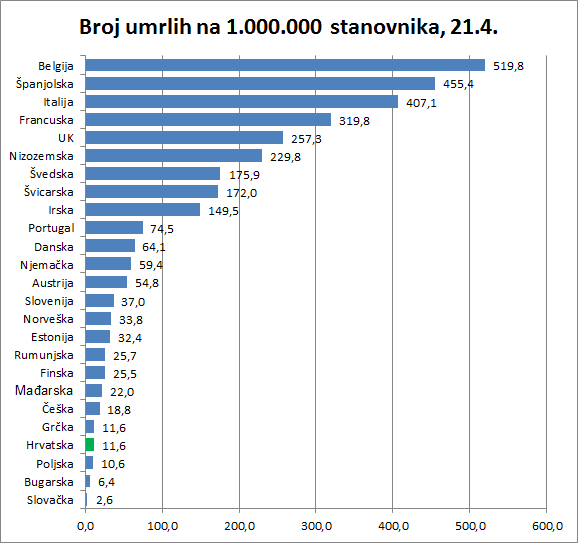

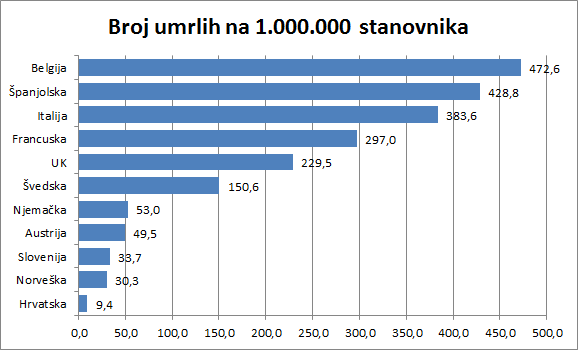

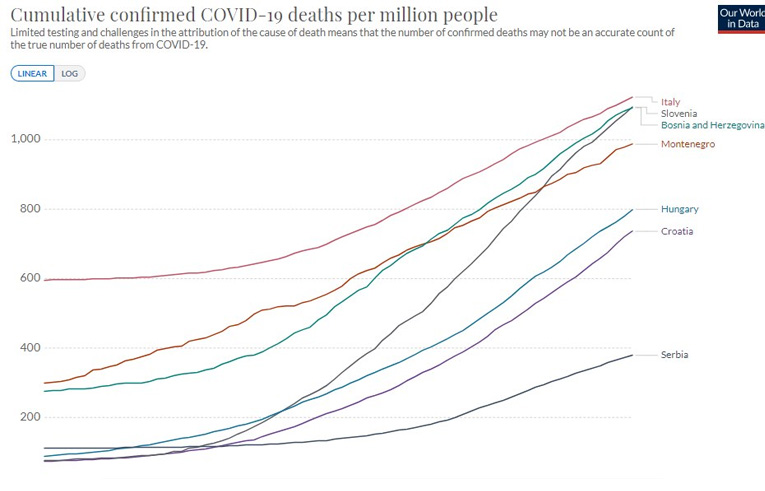

April 22, 2020 — A graph showing the number of deaths from or with the SARS-CoV-2 virus per million population per country places Croatia among the five best-ranked countries with the lowest proportional death toll, according to the Johns Hopkins coronavirus database. In addition to Croatia, there are Greece, Poland, Bulgaria and - according to the available data - Slovakia.

The next group includes the Czech Republic, Hungary, Finland, Romania, Estonia, Norway and Slovenia, with the worst situation affecting Belgium, Spain, Italy and France.

Compared to Croatia, often due to its access to measures to combat the epidemic, Sweden has about 15 times the death toll per million inhabitants.

Specifying only the absolute number infected persons or persons who died from or with the presence of the coronavirus does not give a true picture of the situation. There are huge differences in the population of individual states.

In this way, for example, for a very long time, the terrible situation in Belgium, with its 11.5 million inhabitants in absolute numbers (5,998), had seemingly far fewer casualties than, for example, Italy with its 60,5 million inhabitants (24,648).

It can also be said that Germany with 4,961 deaths has far more casualties than 1,765 in Sweden, which is not really the case. On the contrary, Germany with 83.5 million inhabitants is significantly more successful in fighting the epidemic than Sweden with 10 million inhabitants.

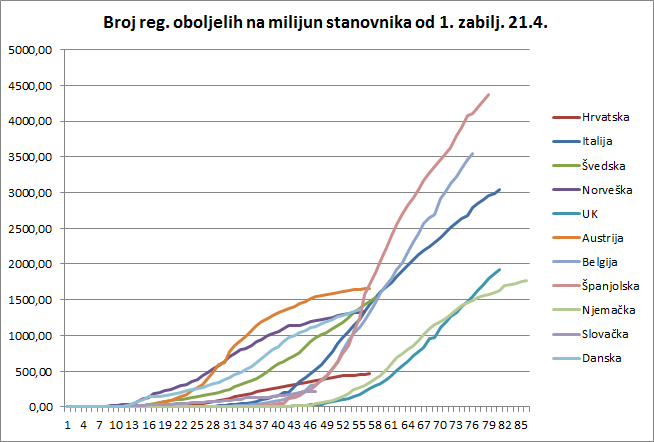

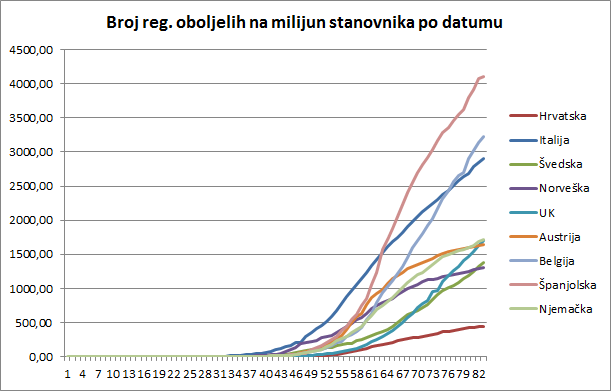

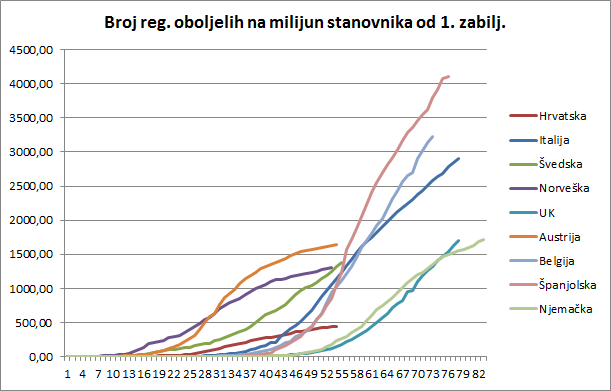

Likewise, it is difficult to compare the development of an epidemic by country in parallel if one looks at the number of confirmed infections persons at the same date, regardless of the outbreak of the epidemic in each country. Instead, we provide an overview for each country that starts on the date the infected person was first registered in that country. In this way, it is possible to compare the development and effects anti-epidemic measures both in dynamics and in relative numbers per million inhabitants.

This chart does not show all the countries that were in the previous one, not only because such a view would become completely opaque, but also because of the abundance of data to be monitored.

At first glance, two groups stand out from the countries observed. The left group is one in which the epidemic developed relatively quickly after the first registered infected person in terms of population: Austria, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Croatia and Slovakia. Of course, these are smaller countries. The right group is one in which more time has elapsed since the first registration of the infected person, and these are countries with a larger population.

In the first group, there was a rapid increase in the number of people infected in Austria, but also a very rapid response that reversed the epidemic as early as the 32nd day, and even without "leveling”, a consistent reduction in the number of new infections was achieved. The epidemic has calmed down after about 50 days in that country, which of course has a great impact on deciding what to do next.

The epidemic in Norway, with an even sharper start, had a similar course. The rapid reaction of the authorities reversed the trend around the 32nd day as well and achieved a calming epidemic around the 45th day.

In Denmark, the epidemic started very similar to that in Norway, but the epidemic’s spread slowed quickly but soon increased again. Currently, the curve is linear.

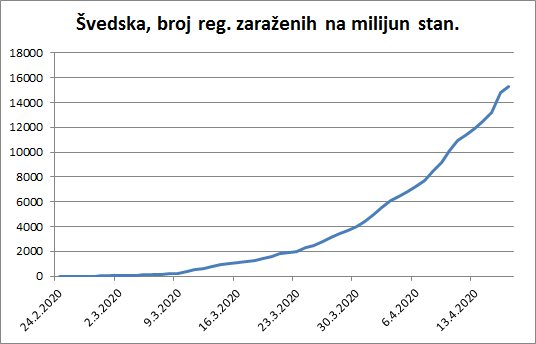

The same group is followed by Sweden, which initially did not have rapid growth but, by the 55th day, has grown in the number of registered infected persons and Denmark and Norway, and there is no sign of a slowdown.

Viewed in this chart, Croatia and Slovakia have maintained a very low slope linear curve since the beginning and have the lowest number of registered infected persons per million inhabitants.

The group of larger countries shows the worst situation is in Spain, which after exponential growth until the 56th day of the epidemic in its territory, was able to achieve a linear growth. Then from around the 62nd day, a slightly milder but still large slope with no indication that the epidemic would soon begin to subside.

It is similar in Belgium, which straightened the curve around the 54th day but has since maintained a steady but high (relative) increase in new infections with no indication of calm.

Italy, whose exponential curve started about a week before the one in Spain, reached a more moderate slope of the linear part of the curve around day 49 and shows a slight calming of the epidemic.

Germany, with some time lag compared to the first registered infected person, has achieved a curve similar to Austria, with a change in trend around the 68th day.

After exponential growth, the United Kingdom was able to straighten the curve around day 70, but without a stronger indication of calming.

Let’s look closer to Sweden. We can see a form of exponential growth in the number of infected.

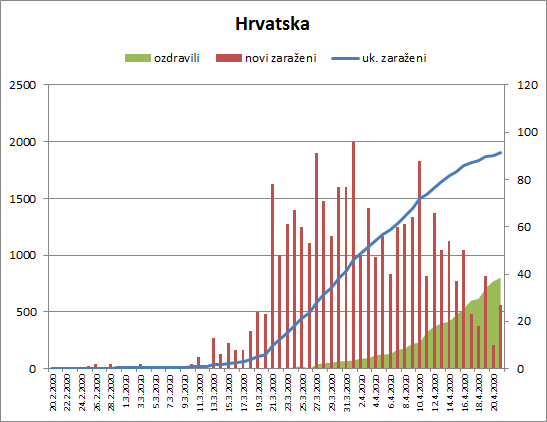

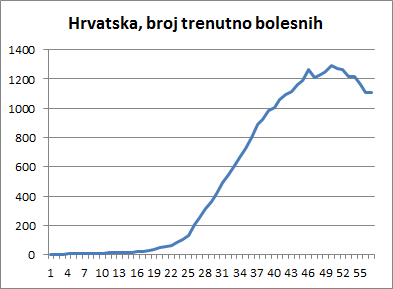

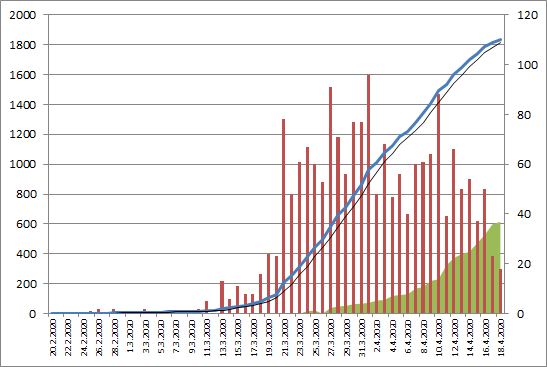

If we take a closer look at Croatia, we will see that linear growth has already been achieved around March 22 (just after the earthquake in Zagreb). An even better curve was achieved after April 1, and that from April 16 it can say it has stifled the epidemic.

Croatia's excellent result can also be seen in the chart showing the number of patients affected.

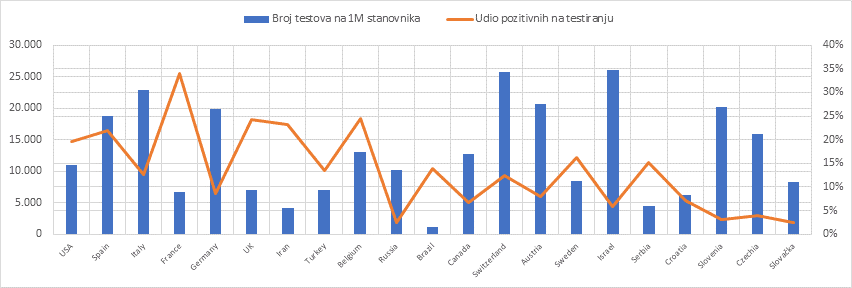

These topics often raise the question of what is a good test measure and whether we are testing enough. An excellent graphical representation of the testing ratio per million population and the percentage of positives shows who optimally tests and who does not. If you are about 10% positive you have found a good measure - Croatia is. Something ugly is coming to Brazil, only if the good weather saves them.

Comparison of the number of tests per million and the percentage of positive ones - by Milan Stevanović 2104

Comparison of the number of tests per million and the percentage of positive ones - by Milan Stevanović 2104

From everything I think it can be concluded how useful it is when policies are established on the basis of scientific knowledge and data. Scientific knowledge, in comparison to the usual political ones, is neither conservative nor radical; they are simply as they are and should be trusted. But these lessons are not exclusively health, but equally political, especially when we talk about loosening up measures.

Of course, any country may be asked what its long-term prospect is in these new circumstances that will not go away. Some countries, which have curbed the epidemic in the sense that they have ensured that their health care system can control the situation, may be far more comfortable developing a further strategy than those who still have to put all their efforts into maintaining the health system's functionality.

And finally - is coronavirus more dangerous than the flu? Yes, but as far as we may know, in just a few months, we learn something new every day. The important difference is that we do not have vaccines and that the virus can mutate more often in a large number of patients.

Krešimir Macan is a public relations professional and political analyst specializing in crisis communications. He has advised two Croatian Prime Ministers, including current Prime Minister Andrej Plenković. He also runs his own PR consultancy, Manjgura.

Krešimir provides TCN with regularly-updated analysis of coronavirus data, helping put Croatia's pandemic response into context.

Richest Town in Croatia Keeps Travel Restrictions, For Now

April 21, 2020 — A tourism hub on the island of Pag opted out of loosened travel restrictions to prevent a surge in new COVID-19 infections during the coming Mayday holiday, which it fears could have repercussions on its profitable summer season.

The decision comes as the rest of Croatia tosses aside an ePass system which created an administrative — if not literal — barrier between municipalities and counties during the first month of Croatia’s lockdown.

A drop in new infections gives local directorates a chance to ease back on restrictions. Novalja said, “No thanks” and received an exemption allowing it to maintain stricter policies.

The head of Novalja’s Civil Protection Directorate Marijan Suljić reportedly told HINA the town will keep the ePass regime, preventing weekend visitors from returning to second residences and vacation homes.

“It may be a case of thousands of people who would come to their apartments when no catering facilities were working,” Suljić said. “Everyone would go out to the waterfront and that's dangerous. With this unpopular decision, we are protecting ourselves and them.”

Novalja made waves with an ad campaign asking tourists to stay at home, a jarring message for a town whose economy relies almost exclusively on a booming tourism season.

The comparatively affluent municipality helped local businesses weather the lockdown’s economic plunge, covering state-mandated social safety net contributions for every worker in the hospitality industry.

Suljić acknowledged the continued lockdown would anger the owners of summer homes and apartments. He said Novalja will welcome back weekenders, eventually, but not at the cost of progress made containing the coronavirus.

To date, the small town had only two cases of COVID-19, a married couple reportedly recovered ready to be declared healthy on Sunday, 28 days after testing positive.

The municipality will probably open to outsiders when hospitality and food service companies resume business.

“We just have to endure a little more because it would be pointless to give up and ruin everything now,” Suljić added.

Analysis: Coronavirus in Croatia Compared to Other European Countries

April 21, 2020 — I received some great observations from a colleague, so I asked him for permission to share them with you. He says that he is getting a little nervous about all sorts of things, and has started to keep his statistics for some European countries that are of interest to him. The statistics end on 04/18/2020.

Otherwise, click here for daily detailed visualizations of coronavirus data in Croatia, and for all our texts on this topic, see the keyword “koronavirus”.

The following are quotes and charts from a colleague.

The point in all the charts is that it makes no sense to express the absolute number of infected or dead or whatever by country because we mix potatoes and locomotives. It does not matter that Germany has over 80 million inhabitants, Belgium 11 million and Croatia 4 million. So I reduced everything to a million inhabitants and then you see things differently than what is said in the media.

Coronavirus deaths per million population

This is the number of deaths from/with coronavirus. Of course, we don't know if all these figures are correct (the source is Johns Hopkins' coronavirus database), but let's say they are accurate enough to see the proportions.

So there is no doubt how good Croatia is relative to the others in terms of deaths. Comparing this with Sweden, the situation is 16 times worse than in Croatia. And we can't compare Sweden to Croatia in any way, and especially not to the strength of the health system or GDP.

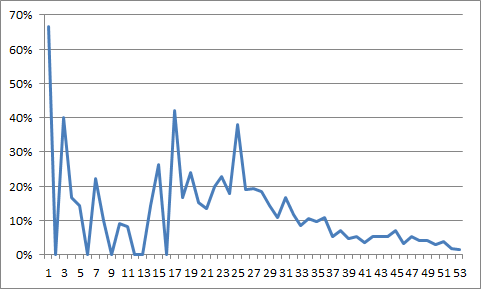

This is a comparison of the number of confirmed infections (the actual number of infected people we do not know) again reduced to one million inhabitants. All start on day 1, even though the first patients registered in different countries on different dates. Here you see too much of the forest to make out the trees. In any case, one can see here who has straight curves, whose grew exponentially, and who has inflected. Who is the best? Croatia.

Number of registered patients per million population, on the same dates, regardless of the fact that the first patients registered in different countries on different dates

This to me is a far better overview. The curves here are not on the same date, but each begins on the date when the first diseased was registered in that country. Here you can see when who reacted and how.

Number of registered patients per million people, on the dates when the first patients were registered

Of course, Spain has the worst curve in terms of relative numbers, but it slowly (unfortunately, very slowly) calms the epidemic. Italy is also slowing the epidemic. Belgium has a terrible situation, but the curve is flat. The worst is the UK, which has barely evened the exponential curve. These countries, including Germany, have waited a long time without serious measures with few infected.

The second group responded quickly: Austria, Norway, Croatia.

Of course, Sweden cannot be said to have truly responded. This is a special case.

It can be seen that, although it had a very rapid expansion of infected, Austria reached an inflection very fast - sometime in the 30th day from the first case, and calmed the epidemic. So there are reasons to loosen the measures.

In Norway, the spread of the infection started very shortly after the first patient, but relatively slowly, and has an even better result than Austria. Germany is also calming down its epidemic, similar to Austria, but the inflection is only about the 62nd day.

Who is the best? Croatia. Importantly, Croatia imported its first patients from Austria and Italy. But it reacted before both countries, a far larger and economically more powerful country. So Capak, Beros and Bozicevic knew what they were doing just in time.

Italy only has an inflection for the 69th day! Had she instituted drastic measures at least 15 days earlier, her situation would have been significantly different.

Number of patients in Croatia and trends

OK, this is known to everyone (I guess). The blue line is the total number of registered infected, the black thin line is a trend, the red columns are daily new infected and the green ones are recovered. It is important to know that Beros tells us every day how many recovered in hospitals and how many at home. This is very important. Many countries do not and have any idea how many (registered) patients have recovered at home.

But on the blue curve, it is very important that there are four areas. The first runs until March 21. when the epidemic started the way the epidemic started. From March 31 to April 1 are the results of the first measures to curb the epidemic. From April 1 to April 16 are the results of another set of measures. After April 16, though it is still too few days, something fourth is happening. Look at the slopes of the curve so you will understand.

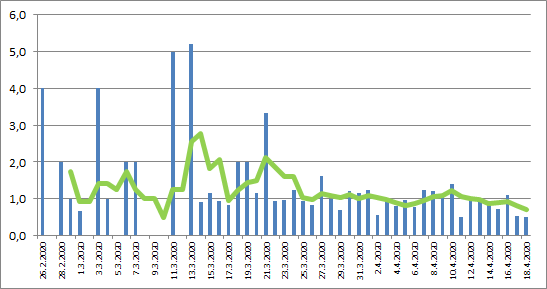

I do not know exactly how the Croatian Institute of Public Health calculates that epidemic spread rate. Here are two ways of looking at it. The first way is looking at how many newly-infected are compared to the “ironed out” total infected. What does “ironing” mean? Croatia is small. A bus from Turkey arrives or a virus enters a home in Split or because of an earthquake we do not process all test swabs that day. But compensate for the next big changes in the curves. That is why I “iron” the curve in two ways, so that such jumps do not significantly affect this coefficient. And here's what I get:

Ratio - how many newborns are compared to a little infested by then

The green curve is important. Not only has it been calm for quite a while (that's when they "leveled" the upper blue curve), but what matters is what has been going on in recent days. For the last six days, this green curve is below one, which means that the spread of infection is decreasing.

But there is one other curve, which is perhaps fairer: the relationship of the newly infected with the currently ill (thus, without recovered)! Here's that one (unironed):

Relationship of newly infected with currently ill (thus, no recovered)

And that's good.

I received more contributions immediately. An excellent graphical representation of the testing ratio per million population and the percentage of positives shows who optimally tests and who does not. If you are about 10% positive you have found a good measure - Croatia is. Something ugly is coming to Brazil, only if the good weather saves them.

Comparison of the number of tests per million and the percentage of positive ones - by Milan Stevanović, April 18

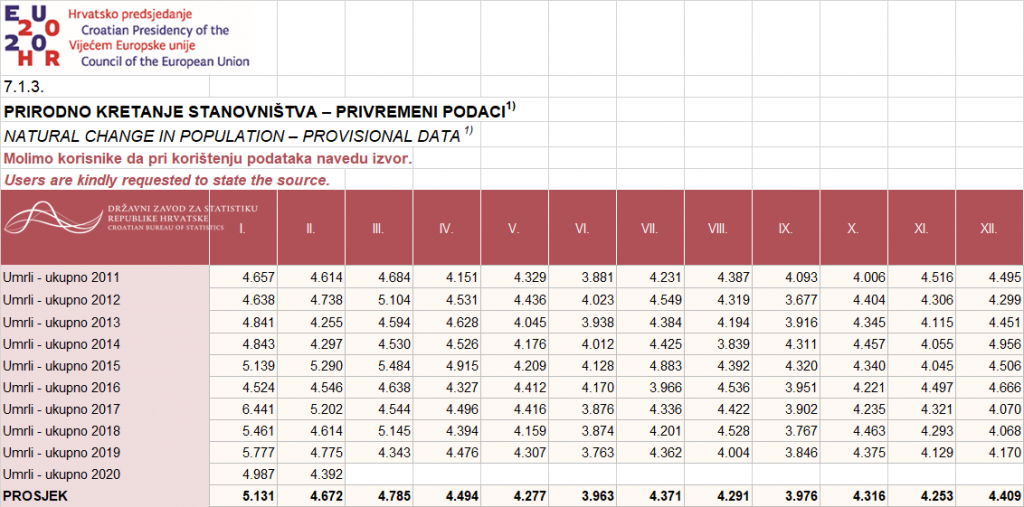

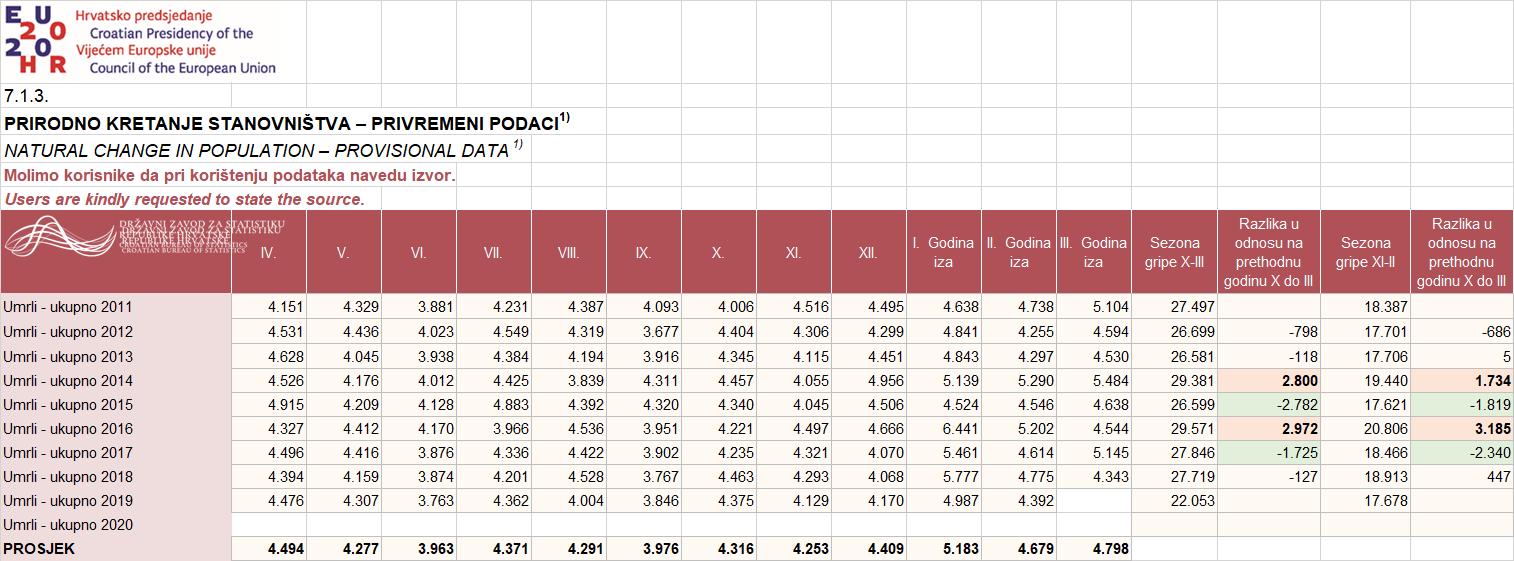

I was also bothered by what Zoran Milanovic told N1: “There are many things for which we have no answers, but we go over them and continue to live. In January 2017, it was calculated that the death toll was 6500 that month. However, a year earlier 4500 people. From what? 2500 people more. There were no car accidents, suicides. Two thousand people have died more than average. It’s a scary figure and we knew it and no one responded. This was probably an epidemic of more severe flu, because in this seasonal prolapse more and more die, and so it is calculated because we do not test for the flu. But when you see that 45 percent more people died in one period than normal in a 10-year average in that month, something happened, we don't know what. "

Some people wanted to interpret it as seeing nothing happens when 2,000 people die from the flu, life doesn't stop. But that's the point - if the measures had not been activated the number of dead would have been at least 2,000 to 4,000 more as they die due to strong flu seasons such as 2014/2015 and 2016/2017 - see the data.

DSZ data on deaths by months

Data on deaths compounded by flu season

If you want to play and check yourself, you can find great visualizations and country comparisons here.

Murter and Betina Quarantine Ends

April 19, 2020 — The first and only quarantine in Croatia is over.

Šibenik-Knin County announced there were no new positive cases of COVID-19 yesterday, and lifted quarantine measures for the Murter and Betina settlements.

The island of Murter was effectively cut off from the world on March 25, after an outbreak of the virus spread across the island. All told the island had 28 confirmed cases of COVID-19, with 14 residents ordered into self-isolation and 162 others undergoing medical checks.

Epidemiologists tested two random groups of people on Murter on April 15 and 16, looking for signs of community spread. The tests came back negative.

"Epidemiologists have concluded that there is no need to extend the quarantine measures for Murter and Betina," the county's Civil Protection Directorate said in a statement. "The quarantine measures for the settlements of Murter and Betina, which have been in force since March 25, 2020, are being abolished as of today."

According to epidemiologists, the current situation in Murter is good. There are still 12 currently in self-isolation. The last new COVID-19 diagnosis came nine days ago.

"Health recommendations are still in place," the directorate said. "All health care measures and guidelines must continue to be respected responsibly. That is why we appeal to all citizens again, stay in your houses, maintain hygiene and respect physical distance."

The virus's arrival on the otherwise secluded island miffed many. Local authorities suggested an asymptomatic tourist visiting earlier in the season may have brought the virus in early-March.

Escapes To Croatian Islands Fall, Association Hopes It Stays That Way

April 19, 2020 — Within days after Italy's country-wide coronavirus lockdown, a few of the country's boat owners sailed for Croatia's coast to avoid the infection in their own country. They arrived in marinas, on island harbors and spent a week galavanting around Zadar's archipelago while local police responded to reports of unregistered foreigners. Some even escaped via ferry to their weekend homes off the Croatian coast, before the government prohibited non-residents from going to islands.

Those days appear to be over. For now.

The early trickle of new arrivals did not become a flood, according to the head of Zadar's Civil Protection Directorate, Šime Vicković. In fact, the number of new arrivals — nautical or otherwise — has fallen close to zero, he told Zadarski List.

The problems first began with boats sailing under Italian flags arriving at Dugi Otok in the first half of March, in some cases overnighting in the Telascica Nature Park before locals reported them to police.

Tensions grew as several Italians and Slovenes took up residence in summer homes on the Dugi Otok. Neighboring islands reported a similar influx of locals during the early stages of Croatia's coronavirus response. Their compatriots did not follow them.

"All these reports are controlled by the Maritime Police, and our headquarters had a report on boaters coming to Sali, but since then we have no more reports," Vicković told Zadarski. "Those who have entered our waters are monitored by the police, warning them that they are obliged to check in if they remain here in their property and, of course, to go into self-isolation."

Croatia's islanders, or boduli, expressed dismay over the unexpected arrivals. Many were not registering with Croatia's eVisitor system, living off the radar of authorities and giving a rosier picture of the state of the islands.

Locals also worried about their population, which skews towards pensioners and those most susceptible to the virus.

The situation is, however, much different now, especially since the number of those infected is in a slight decline. The national Civil Protection Directorate's decision to prevent non-residents from traveling to islands prevented Croats, Slovenes and Italians fleeing to their vacation homes. The move may have prevented outbreaks on islands.

The president of the Croatian Islands Association, Denis Baric, appealed to the authorities to continue to protect islanders as the government mulls loosening restrictions.

"Following the situation, we must appeal to the competent authorities to do everything possible to protect our islanders, who, due to their age, are the largest crisis group," he wrote in a statement. "We are aware that every day that business owners do not work has a direct impact on their survival, and presents a direct threat to their employees. We are all anxious today for our future existence, but we are determined that we will put the life and health of every individual first."

For now, only persons residing on the islands are allowed to purchase ferry tickets to go to islands, as well as those with ePasses. The latter has become a point of contention for some, as newer faces with tenuous connections to islands show up.

Barić said the islands had a strong network to help the elderly, benefiting from the sort of small-town environment where everyone knows everyone. The Islander association said allowing non-residents to migrate to islands at this moment is akin to allowing COVID-19 to spread on Croatia's islands.

The perception of a Croatian island as an oasis against COVID-19 remains true, with the exception of Murter. Infections along the Adriatic remain relatively low, compared to larger urban centers.

"We cannot help but look back and urge the authorities to do everything possible to protect our islanders, who are the largest crisis group because of their age structure," Barić said.

Croatia's 3D Printers Ease Medical Supply Shortage

April 15, 2020 — The coronavirus crisis activated 3D printers across Croatia, with an impromptu unification of about 100 people all around the country providing medical professionals with much-needed supplies, according to Jutarnji List.

Among the more active are Osijek residents, who have printed about five hundred protective visors for medical professionals every week since the crisis began.

The whole initiative started virtually, via a Facebook group.

"We have a group called '3D print experts Croatia,' which is the largest gathering our kind in our country," IT expert Valent Turković told the paper. In addition to making visors, he and a colleague coordinate the collection and distribution of 3D-printed materials to area hospitals.

"The idea started from many directions, from all over Croatia. Medical visors of this kind are a new solution, recently created in the Czech Republic," Turković added.

In accordance with the huge demand for protective medical devices, the Czech company Prusa3D designed the mask and made its schematics public.

"This information immediately came to our group and people started printing, and some even optimized the design," Turković said, adding that Split's University was among the first to start production systematically.

People with 3D printers and enthusiasm for helping began to appear on all sides. Turković said the Facebook group created questionnaires for everyone and then grouped people together by region to bring together those with more and those with less experience.

One or two people were selected in each city to collect masks and deliver them to hospitals.

"Often, people often want to take the mask to the hospital as soon as they print the mask, but for security reasons, it is definitely a recommendation that they contact us from the group and allow us to make the delivery," Turković added.

The biggest challenge for them right now is getting plastic parts for visor masks, that is, films or resistant overhead films.

All the masks they make, he says, go to public health services for free. They receive inquiries from private clinics, which they reject.

The masks protect the whole face and covering the eyes, though doctors still wear surgical masks underneath them.

The solution, doctors said, is much better than plastic glasses, which blur their eyesight and often fog up. Turković the 3D printers cannot keep up with demand.

"We try our best to supply everyone, but we just need time," he said.

The electrical engineering school in Varaždin has designed how to print protective visors for doctors faster and cheaper on 3D printers.

The first model, created by a Czech 3D modeling company, required eight hours of printing for one visor, and the Varaždin residents reduced this to one hour per visor. This also reduced the production cost from HRK 40 apiece to about HRK 25.

Two doctors from Varaždin General Hospital suggested printing the visors when the school took the idea and ran with it.

Overall, the campaign, led largely by the student population, is attended by people from 45 cities with about three hundred 3D printers.

It all started at the FESB in Split and the Student Union of the University of Split got involved, who shared the student invitation on Facebook and the avalanche was triggered. In less than 18 hours after the announcement, 120 students and about a hundred 3D printers joined the action.

Printers have emptied domestic plastic material suppliers. Specifically, a special plastic material used in printing, costing up to HRK 200. Fortunately, all those who have the material who don't have printers donated their supplies and quickly returned production to full capacity.

Croatia's "Relaxed Restrictions" Debate Takes Shape

April 15, 2020 — While some EU member states have begun to open up their economies, Croatia remains quarantined. Despite the growing pressure from businessmen to begin the process of unfreezing the domestic economy as soon as possible, the Government is not giving up a millimeter of its restrictive “policy corona” as of now, according to Jutarnji List.

"There are pressures, we are aware of that," a source within the government told the paper. "However, we will only be able to consider abolishing certain measures and prohibitions when the epidemiological picture permits. So far this is not the case yet."

A process of gradual unwinding began on the European Continent this weekend. Spain allowed almost two million construction and industrial workers to return to work. Italy opened bookstores and children's clothing stores. Denmark opened schools for students. The clearest plan to exit the "corona regime" is implemented by the Austrian government, where all stores up to 400 square meters are open. If there is no significant increase in the number of new infections, they will open all other shops, shopping centers and some services such as hairdressing and beauty salons on May 1.

Does the Croatian Government have at least a preliminary plan for reopening the economy?

"It works on various models, but it's still too early to talk about it. There are no comparisons with Austria," the government source told Jutarnji. "Their curve of the daily number of newcomers has been going down for some time, and here the curve is oscillating.

"The number of new patients has to fall five to ten consecutive days to consider the phasing out of individual measures. While the number of new cases fluctuates between 40 and 70 per day, it is not yet time for that."

It leaves Croatia in the same precarious situation as many other nations — squeezed between keeping a pandemic at bay while also hurting an economy.

"It is important that we be careful when withdrawing the measures," Branko Kolarić, Head of the Public Health Gerontology Department of the NHIF “Dr. Andrija Štampar” told Jutarnji. "The measures are intended to preserve the life and health of people and prevent the collapse of the health system. In addition to physical health, there is also mental and social health. The economy and standard of living are also determinants of health and longevity."

While there is no clear answer from the government on how long the quarantine will last, economists Velimir Šonje said that the economy must be started immediately.

"From an economic perspective, irreparable damage has already occurred and the only economic sense is to start the economy immediately in order to try to return to the point we were in February this year in a year or two," he said. "Now that is still possible, with luck. As time goes by in this isolation, the likelihood of such a happy outcome will be less and less.

"If the Germans calculated that their economy could not withstand more than 11 weeks of such a regime, and we know what the German economy is and what the strength of their measures is, what do you think is the endurance limit for a weak economy like the Croatian one that operates with an indebted country?"

Šonje added it is necessary to open the now-closed section of trade and the service sector "with the necessary modalities to comply with anti-epidemic measures," as soon as possible.

The National Civil Protection Directorate has not said when — or whether — it will extend the restrictions on work and movement set to expire on April 18.

The headquarters passed the largest package of restrictive measures - from the ban on the operation of cafes, restaurants, hairdressers and beauty salons, through cinemas, swimming pools and gyms, until the ban on serving masses and operating a driving school - on March 19, with a 30-day deadline.

"Croatia is too small to recover as a closed economy, whereby I don't just mean tourism because this branch is hit hard anyway," Šonje said. "It is important to monitor data, harmonize measures, and integrate some information systems and protocols in the future because Central European economies are closely linked, and the flow of goods and services, which is vital for all these countries, depends on the people."

Kolarić warned against rushing through reopening the economy. "The world has never stopped this way," he said. "When we have already assessed the threat of this contagion to the global and significantly reduced personal freedoms and so-called a free market, it is important that when withdrawing measures we are careful not to spoil what we have done well."

Croatia's Historic Quarantine: The "Lockdown" of the Ottoman Empire

April 13, 2020 — Croatia is earning plaudits for its handling of the coronavirus. But not many realize it has plenty of practice throughout history — besides Dubrovnik’s invention of the quarantine. Just thank the Habsburg Monarchy.

The sanitary cordon, corralling whole nations to mitigate the spread of disease, was first implemented on Croatian territory. The Habsburg Monarchy used it first, placing 10,000 guards along a 1,900-kilometer border to prevent the plague from entering via the Ottoman Empire, according to historians.

Although there have been many examples of sanitary cordons in various parts of the world before, in the 18th century the Croatian-Slavonian military landscape was the most extensive and one of the most permanent systems of permanent land quarantine protection in the entire history of humanity, historian Hrvoje Petrić told Jutarnji List.

A sanitary cordon, or “lockdown” in modern terms, is a system of measures around an infected area preventing the transmission of disease. It consists of checkpoints, stations and places where health check-ups are carried out. People and animals are isolated, and all items that can transmit the disease from an infected to an uninfected area are disinfected.

Due to the frequent spread of plague and other infectious diseases from the Ottoman Empire, the Habsburg Empire’s Military Frontier has also become a sanitary cordon. The border was initially organized as a defensive zone against the Ottomans, extending from the Adriatic Sea to the Carpathian Mountains. The area has since grown into a separate political, military, economic and social phenomenon.

Various anti-epidemic measures have existed on the border with the Ottoman Empire since the end of the 17th century, but the foundation for the development of continuous protection is the Imperial Patent on the Protection of the Plague of 1709, says a historian at the Faculty of Arts in Zagreb. He noted that the patent is a response to the plague epidemic which had broken out two years earlier. It included quarantine measures at specific points at the border.

The Sanitary Council, which was initially a body of the lower Austrian authorities, eventually took over the anti-epidemic defense of other Habsburg countries and became a Court Health Commission in 1719. The commission had the authority to send surgeons and physicians in epidemics to vulnerable areas and to direct anti-epidemic activities through regulations.

The Habsburg Monarchy was an absolutist force capable of reviving orders from above. It is therefore not surprising that the patent of Charles VI. October 22, 1728, prescribed the creation of a permanent sanitary cordon as continuous anti-epidemic protection on the border zone of the Habsburg Monarchy, says the historian Petric. The belt stretched from the Adriatic Sea to the Carpathian Mountains for a total length of 1900 kilometers.

Quarantine in Practice

The sanitary cordon relied on quarantines and permanent cordon guards, but also on the system of collecting health information in the Ottoman Empire. The first containment stations, modest wooden barracks where suspected passengers were isolated and goods were disinfected, were erected around 1730–1740 along the Una and Sava rivers.

The prescribed quarantine lasted 42 days, and sometimes up to 84 days. This, however, led to problems in trade between the two empires. Therefore, the Habsburg authorities in 1768 allowed the establishment of neutral zones, where trade could occur since neither the buyer nor the seller came in direct physical contact, Petric said.

The Venetian Republic also established a permanent sanitary cordon towards the Ottoman Empire after the signing of the Peace of Pozarevac, 1718. It extended from the Habsburg-Ottoman-Venetian tribe to Neum.

It took about 4,000 soldiers to guard the cordon. However, if an epidemic were to occur in Constantinople, 7,000 men would be sent on guard duty, leaving 11,000 men to stand guard against the plague. For all who came from the Ottoman Empire, the quarantine lasted 21 days in 1770 but could be increased to 28 and 42 days, if necessary.

The guards were at a safe distance from the passengers because otherwise they would be subjected to quarantine measures themselves. Contact with people from the Ottoman Empire who did not pass quarantine was strictly forbidden.

The goods traders carried were conserved. The new arrivals were examined by doctors in a separate room in which people were separated by a double row of narrow beams, spaced about two meters apart.

They were also questioned by the account manager, to assess the risk of spreading the infection. In doing so, he also collected other information about the health of the area they came from. In some places rested huts, each with four compartments. One section was a living space, a small kitchen and a fenced yard with a water closet, and as a rule, it housed one passenger. Otherwise, care was taken to accept as few individuals as possible, and those who would show signs of illness were immediately returned to the Ottoman Empire, Petrić said.

The Quarantine Life

There is some evidence of life in quarantine. Traveler Savior Lusignan wrote, “I arrived in Zemun yesterday. After the quarantine doctors examined me as well as my clothes, a gentleman from Smyrna received me at the apartment because all the hostels were occupied… ”

On the other hand, in the area under Venetian rule, the experience of a certain John Howard has a more fun anecdote. In a book from 1789, he states that “the Lazaretto in Herceg Novi in Dalmatiaæ is ”located on the coast, about two miles from the city."

“A beautiful hill rises in the background of the lazaretto. Quarantined people are allowed to go there after a few days and enjoy hunting and the like.”

However, it was clearly not so good for Jakob Mušinović from Kutina. In 1775, he escaped from quarantine and hid in the courtyard of the Franciscan monastery. He was soon arrested and quarantined. The monastery’s chronicle notes, “We have managed to preserve our health. Otherwise, if he had found the monastery door open, he would have entered either the bakery or the barn, and the monastery would surely have been closed."

The sanitary cordon has reduced the spread of epidemics, but not entirely. The plague managed to get past the cordon at least five times.

Jet Set Social Distancing: Croatian Chartered Plane Turned Back in France

April 10, 2020 — A Croatian businessman wanted to treat friends to a holiday in France’s Côte d’Azur, chartering a private jet from London last Saturday then pulling the tried and true practice of “calling connections” to get around a ban on travel. Pandemics, travel restrictions and social distancing rules be damned. French police greeted the group with a resounding “non”, cut short their holiday and sent the group back to the United Kingdom, according to the Guardian.

The nixed vacation comes just as Croatia’s own restrictions on movement and social isolation policy incrementally unravel. Various reports claim cafes and other shops operate around the country in clandestine fashion, religious ceremonies are green-lit despite epidemiological dangers, and even the bureaucracy meant to restrict movement creates loopholes for itself.

Seven men, ages 40-50, and three women, ages 23-25, took the charter flight to Marseille-Provence airport, with three helicopters waiting to fly them to a luxury villa in Cannes. A Croatian businessman who works in finance and real estate chartered the flight, the paper reported. The group was made up of several nationalities, including German, Romanian and French.

Authorities forbade the plane’s arrival while it was still in the sky, but the pilot landed anyway. The group then took nearly four hours to leave.

“They tried to make use of their connections and made a few phone calls,” a source in the police told BFMTV.

“They were coming for a holiday in Cannes and three helicopters were waiting on the tarmac,” a border police spokesperson told Agence France-Presse. “We notified them they were not allowed to enter the national territory and they left four hours later.”

The helicopters were sent away and fined for ignoring lockdown rules, which banned all non-essential travel since March 17.

The Croatian businessman might have taken a cue from his homeland, where good figures have created a sense of security and an increasingly-lax attitude after weeks of successfully “flattening the curve” through strict isolation measures and limits on travel.

The decision to re-open Zagreb’s open-air market in Dolac drew crowds for the first time since an earthquake sent residents rushing out onto the streets. The government-sanctioned travel system, which uses “e-passes” to allow citizens to travel across municipal borders has become a leaky dam. And authorities let a Catholic Church tradition be an exception to requests everyone stay at home despite the Easter holiday weekend.

Croatia's Liberalized Travel System Hits Bureaucratic Speed Bump

April 9, 2020 — Vera Blažek from Cakovec biked five kilometers to a supermarket yesterday afternoon, preempting pensioners and the crowds that come with them. The 68-year-old technically broke the law.

It takes about half an hour to get around the bike path. But reach the Čakovec shop from her Čakovec address, she needs an "e-pass,” she told Jutarnji List. The Municipality of Šenkovec dips into Čakovec a few kilometers along the main road. The bizarre shape and lack of continuity has made Croatia’s e-pass system a confounding mess for local authorities wanting to grant some mobility to citizens, while still preventing the virus’s spread.

Croatia’s multi-tiered municipal and county governments are clashing over loosening restrictions on the movement of healthy residents via the e-pass system. The government has issued 700,000 such passes to residents claiming a need to leave their neighborhood.

Some local authorities want free movement, others fear undoing keep the current system’s effectiveness against the coronavirus. The countries convoluted delegation of government duties doesn’t help.

Oddly shaped municipalities and cities overlap and puncture each other at odd angles. Stand on one street corner, and the opposite side may follow a different bureaucratic regime. Crossing any of these haphazard borders requires a legal document. Which makes Blažek’s casual trip to the supermarket, technically, illegal.

No one thought about the territorial borders, nor did they seem important until the emergence of coronavirus spurred travel restrictions. Now a trip to buy provisions requires a government pass.

“Well, I don't need a pass to go to Čakovec,” Blažek told the paper. “I’m from Cakovec.”

Josip Zerjav has a pass to get to work in Varaždin County — a 15-minute trip through several commuter municipalities. “My pass is worth the exact route,” he said. His grandparents live two kilometers off the route. “I need a pass to get to them,” Zerjav said. “That doesn't make sense.” Not that authorities are enforcing the rules.

Police officers monitor the entry points to Međimurje County, but not the municipalities which make it up. The government has yet to approve the Međimurje County’s proposal combining its constituent Civil Protection Directorates, turning all of its smaller parts into one large, pass-free zone. But Međimurje and police officers are tacitly already implementing it.

The National Civil Protection Directorate hasn’t approved territorial mergers of local civil protection authorities, other than in Istria. Several local leaders are backing away from the idea, worried it’ll undo Croatia’s carefully executed and, so far, successful nationwide lockdown.

The leaders of several local civil protection directorates have refused mergers, worried large numbers of people will come into their territory overnight and, potentially, expand the epidemic.

The effects of the loosening restrictions are already showing. More residents and cars are on the streets. Long lines now form in front of shops, some ignoring the mandated social-distancing rules.

The city of Duga Resa, for example, has a population of 12,000 and covers an area of 58 square kilometers. If the proposal to "merge" four neighboring municipalities - Bosiljevo, Barilovic, Generalski Stol and Netretic - were adopted, the number of residents traveling without e-passes would increase by about 10 thousand, while the free-travel area would increase to about 500 square miles.

Interestingly, many "agricultural counties" do not want the liberalization of the e-Pass regime. The Vukovar-Srijem, Požega-Slavonia and Virovitica-Podravina counties, for example, will not submit proposals for enlargement to the National Headquarters. The same is true in Varaždin County.

"When the national headquarters, based on current figures, conclude that the time has come for the loosening, we will certainly support it," Varaždin County Civilian Protection Chief of Staff Robert Vugrin told Jutarnji.

He also believes that with such decisions, one must also take responsibility if the plans backfire: the large number of people traveling will make the virus will spread faster.

“I understand that there are specific spaces, but it should then be clearly defined which and why exactly. Because like this, with more and more requests, this is no more an exception than a rule,” said Vugrin, noting that he does not like the current situation because it 'creates a mess'.

In that county, they believe the current model of e-passes needs work. Among other things, pass holders do not specify their route, which loses control over the movement of residents once inside another city’s borders.

The City of Varazdin wants to merge the city area with 10 neighboring municipalities, even though Varazdin County opposes the rule.

The mayor of Varaždin, Ivan Čehok, on his FB profile, commented on the city proposal, but also on those who consider it dangerous, including Vugrin in Varaždin County.

“I have seen counterarguments, however: we do not encourage this to travel anymore, it is an area of otherwise daily migration,” Čehok wrote.

The debate has yet to reach a head, and with many mayors and county heads balking at the chance to unite, e-Passes may continue to be in high demand.