Croatia’s Most Spectacular Vineyard: Sea, Stone and Sparkling Wine of Bakar Bay

March 4th, 2022 - For centuries, the steep slopes of Bakar bay have been covered in terraced vineyards built in dry stone. A look into the iconic sparkling wine Bakarska Vodica and the passionate local community that rekindled the tradition and saved the brand from oblivion

There’s a small town in the Northern Adriatic that once used to be three times as big as the capital. In terms of population, that is: at the turn of the 19th century, Bakar was the most populated town in Croatia.

A lot has changed since then, including the landscape of the once idyllic coastal town. In the 1970s, the Bakar bay was transformed into an industrial zone featuring a coke plant and a bulk cargo port, complete with an oil refinery in the nearby Urinj. The plant closed down in the late 90s, but it took a lot longer for the town tainted by decades of pollution to shake off the stigma and focus on brighter things ahead.

Bakar / TMaras, Creative Commons

Bakar / TMaras, Creative Commons

Looking at the remnants of Bakar’s industrial past lining the bay, you would never think that the area used to be known for prolific wine production. And yet it was, and even though the centuries-long winemaking tradition was briefly interrupted, the area is now regaining its fame thanks to the herculean efforts of the local community.

The story of Bakar wine begins in the 18th century, when Empress Maria Theresa granted Bakar the status of a free town complete with all related privileges. The empress encouraged the wine trade, going so far as to exempt those who cultivated the land for the purpose of grape growing from paying taxes for a period of five years.

The local populace jumped on the opportunity and the steep Bakar coastline soon turned into one big vineyard, but the specific traits of this geographic area meant that people had to get creative.

Praputnjak - kulturni krajolik Facebook

Praputnjak - kulturni krajolik Facebook

First of all, there’s bura. The mighty wind wreaks havoc in this part of the Adriatic to such a degree that it inspired a saying: bura is born in Senj, gets married in Bakar, and goes to Trieste to die. With a good part of the Bakar coastline fully exposed and facing the open sea, something had to be done to shield the grapevines from the wind’s destructive force.

There’s also the rugged karst terrain, not exactly the most favourable environment in terms of agriculture. The barren slopes had to be painstakingly cleared of stone and what little vegetation there was, followed by enrichment of the land with fertile soil brought over from the hinterland.

To ensure all of this stayed in place, the local population built dry stone walls, creating vast terraced vineyards that are known in Croatian as Bakarski prezidi. And while dry stone walling is a staple of traditional building in Croatia, rarely is it found in such a unique form: steep slopes criss-crossed with walls, running almost all the way down to the sea.

Given the challenging terrain, it took eight hours of work for one person to build 1,5 cubic metres of dry stone wall. Soil had to be brought over from the mountainous hinterland, either on foot or on carts, prolonging the construction process.

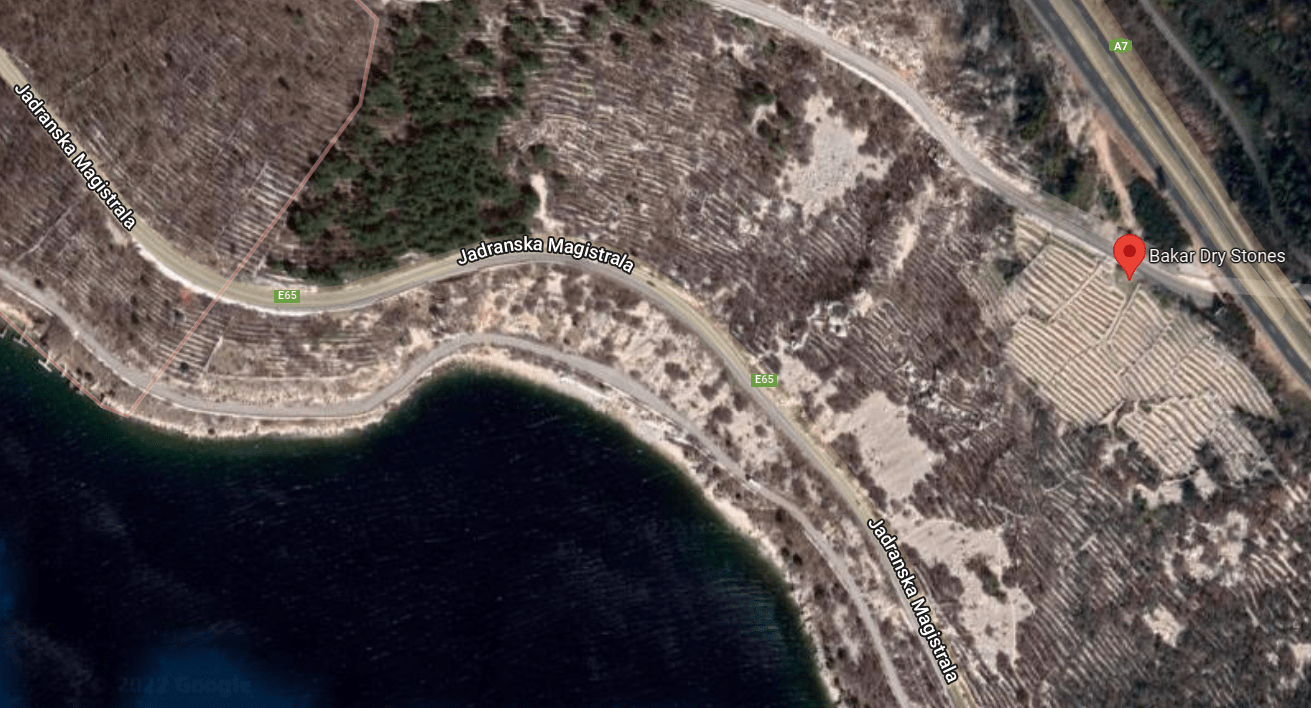

And yet, by the end of the 18th century, dry stone terraces covered 42 hectares of land on the Bakar coastline, entirely cultivated with grapevines. As seen from above, minus the grapes:

The dry stone walls of Bakar, with the most recently restored area seen on the right

The dry stone walls of Bakar, with the most recently restored area seen on the right

The local population, mostly that of the nearby village Praputnjak, grew the belina grape variety used to produce a renowned sparkling wine named Bakarska Vodica (Bakar Water).

It’s speculated that the methods of sparkling wine production were introduced in this region by French soldiers during the Napoleonic era, or perhaps by Bakar shipowners who at the time did business with France. Either way, it didn’t take long for winemaking to become one of the main sources of livelihood in the area. All the families in the region took part in the grape harvest, and the tricks of the trade were taught to children from an early age.

With most men employed at the local shipyards or out at sea for a good part of the year, women took on a lion’s share of the work and were proficient in every part of the wine trade, from cultivation to winemaking. Men typically took on the more physically strenuous tasks such as the construction and maintenance of the dry stone walls.

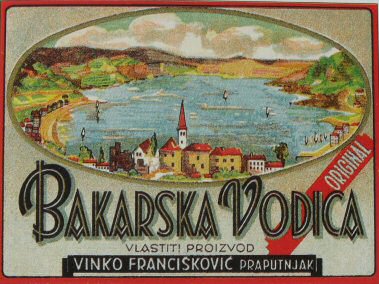

A vintage label design for Bakarska Vodica / Public domain

A vintage label design for Bakarska Vodica / Public domain

For centuries, Bakarska Vodica was produced in the Bakar region using the ancient method known as méthode rurale, which involves bottling the still-fermenting young wine so it would produce CO2 in the bottle without the need for a second fermentation process. It was made of indigenous white grape varieties, belina for the most part, as well as žumić, vrbić, verdić, žlahtina, gustošljen, brankovac and white muscat.

Bakarska vodica was historically held in high regard and was seen as a brand of the region. A wine law passed in 1930 reads:

The name Bakarska Vodica can only be used for natural sparkling wine produced in Bakar and its environs from grapes grown in the area and using the traditional method.

And:

Bakarska Vodica is a natural sparkling wine from the Croatian Littoral. The fermenting young wine (mošt) is bottled and stored in a cold environment.

Speaking of branding, the Bakar wine was talked about as early as 1910, with a state decree saying:

The name 'sparkling wine' is to be featured on bottle labels, printed in large and easily legible letters that draw attention. The label is to be affixed in such a way that it can only be removed from the bottle by being soaked in water.

Bakarska Vodica was not to be messed with. And so it went on until WWII, when production came to a halt for a number of reasons varying from grapevine diseases to legal regulations.

Its real fall from grace began in 1960, when the company Istravino adopted the name Bakarska Vodica for a low-quality sparkling wine made by carbonation and bastardised the poor historic brand. Over time, they reached an output of 2,5 million bottles a year, made possible by low manufacturing costs and partially outsourcing production to Slovenia. The faux Bakarska Vodica is still available on the market, nowadays produced by Mladina in continental Croatia.

This could have been the end of Bakarska Vodica, were it not for a passionate community of Praputnjak locals who decided to roll up their sleeves and reinstate one of the region’s most recognisable brands. In 2000, the Agricultural Cooperative Dolčina from Praputnjak (Poljoprivredna Zadruga Dolčina) launched an initiative to restore the old vineyards and save the belina variety from extinction.

Praputnjak - kulturni krajolik Facebook

Praputnjak - kulturni krajolik Facebook

It made perfect sense to start at Takala, a location east of Bakar that the Ministry of Culture declared a protected cultural landscape (ethno zone) in 1972. Takala was historically cultivated by the people of Praputnjak, and the land plots are owned by the locals to this day. In the local dialect, the name Takala means ‘poured downhill’ - very appropriate in this context.

By 2002, eight dry stone terraces were restored, the land cleared after decades of neglect, and the first 280 belina seedlings ceremoniously planted before a delighted crowd. Little by little, the vineyard grew in size, soon yielding a large enough harvest for the famous bubbly to be reintroduced under the name of Stara Bakarska Vodica (Old Bakar Water).

Stara Bakarska Vodica / Kašetica

Stara Bakarska Vodica / Kašetica

Fueled by unrelenting enthusiasm, the project marches on. It was made part of the Rijeka 2020 - European Capital of Culture programme as an initiative entitled Praputnjak - Cultural Landscape.

Together with the Dolčina association and the Dragodid project dedicated to preservation of dry stone masonry, the Praputnjak crew organise wall restoration workshops, with eager volunteers gathering to help rebuild the dry stone terraces. It’s all done by hand, as mechanisation isn’t an option given the specific terrain.

Praputnjak - kulturni krajolik Facebook

Praputnjak - kulturni krajolik Facebook

Nowadays, the Takala vineyard yields some 1,000 bottles of sparkling wine per year. There are no plans for mass production and the wine is not meant to become commercially viable; it’s purely an effort to rekindle the old tradition and save the heritage of the Bakar area.

Praputnjak - kulturni krajolik Facebook

Praputnjak - kulturni krajolik Facebook

With Bakar eager to shed its industrial image, efforts are being made to restore the charming town to its former glory. There’s been a noticeable shift towards tourism in recent years; significant investments are being made in public infrastructure, the historic Hotel Jadran is reopening later this year as a four-star facility, and tourism professionals are developing new attractive ways to showcase the vibrant heritage of Bakar. The iconic sparkling wine, together with the spectacular stone vineyards, is just the cherry on top.

Quotes featured in the article were translated from a feature on the dry stone walls of Bakar written by Vjekoslav Tićak and published in Sušačka Revija.