Exploring Croatian - The Oldest Known Slavic Alphabet - Glagolitic

January the 2nd, 2023 - Did you know that Croatia once used the oldest known Slavic alphabet? The Glagolitic script can still be seen in various parts of the country, and souvenirs sold across Croatia still bear it to this very day.

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian. What about Glagolitic?

A (very) brief history

To start off, it's worth noting that the origins of the Glagolitic alphabet are disputed to an extent. This can be said for most ancient languages and linguists are known to squabble over such things, but it is generally accepted that the script was created back during the ninth century by a monk from Thessalonica (today's Thessaloniki in Greece) called Saint Cyril, as well as to Saint Methodius, his brother. The very first observed mention of the word ''Croatia'' in the Glagolitic script dates back to around 1100 AD.

Another interesting fact about Glagolitic is that the precise number of letters in its original form is entirely unknown, but what we do know is that it is likely that Saint Cyril and his brother Methodius created the script in order to facilitate the introduction of the Christian faith, and we can assume with some level of certainty that the initial number of letters would have close to a Greek model. That said, there are elements of a variety of different languages within Glagolitic.

Over the many years, Glagolitic evolved with the population of its users and the tumultuous times they faced. It is certain that during the twelfth century, as Glagolitic in its original form (even with its non-Greek sounds) began to lose its grip, more and more Cyrillic influence could be found. As the centuries rolled on, more and more original Glagolitic letters were dropped, seeing the original number of letters drop to less than thirty in the Croatian recensions of what was called the Church Slavic language.

The use of the Glagolitic script in Croatia

The first Croatian Glagolitic book to be printed was Missale Romanum Glagolitice from 1483, and if you somehow managed to obtain a fully functioning time machine and took a quick trip back to the twelfth century and landed anywhere in Kvarner, Istria, Dalmatia, or even in Medjimurje, you'd have come across the Glagolitic script more or less everywhere. It's true that Glagolitic was mostly found in the coastal parts of the country, with notable areas being islands such as Krk (the Kvarner area) and the Dalmatian islands which sit just off the Zadar mainland, but traces of it stretched to Medjimurje (far inland), Lika, and even in parts of modern Slovenia.

For a very long time, it was accepted that the Glagolitic script was used solely in the aforementioned areas, but when 1992 rolled around and Croatia was engulfed in some extremely difficult times in its fight for independence and against Serbian aggression, some fascinating discoveries were made in old churches situated along the Orljava river in Eastern Croatia (Slavonia). This rather remarkable discovery blew previous theories about the locations in which this ancient script was used out of the water, and proved that it was also indeed used in Slavonia, something that was simply not even considered before.

While the twelfth century was in some ways a form of peak for the old Glagolitic script in Croatia, it did survive beyond that as the nation's main script, and for some time, but after a while, the development (or indeed decline) of this script was very poorly documented for a variety of reasons. Just before the marauding Ottomans began sniffing around the area, and before the Croatian-Ottoman wars truly began, the use of Glagolitic was at its very peak, and in today's measure, the amount of people using it back then would correspond to the amount of people in Croatia who use the Chakavian and Kajkavian dialects (two of the main dialects which make up modern standard Croatian) today.

The Ottoman wars and the decline of Croatian Glagolitic

The Ottomans and their invasions in the surrounding areas sounded the death knell for Croatian Glagolitic, and its stability in the region began to slip severely, with more damage being done to the use of this old script in areas more devastated and culturally altered by the Turkish forces. While the Ottomans certainly laid the heaviest of the groundwork to put the nails in Glagolitic's coffin, the real blow which set the wheels in motion for Glagolitic to meet its fate came much, much later, more precisely in the seventeen century, and by a bishop from Zagreb, no less.

The Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy, the west and the Italians

You've likely never heard of this conspiracy, as it's known in Croatia by this title, but to others it is simply called the Magnate conspiracy. In short, this conspiracy was an organised attempt to remove foreign influences (read Habsburg) from both Croatia and neighbouring Hungary during the seventeeth century. This left the Glagolitic script entirely without secular protection, and its use was severely limited, seeing it used only in the coastal region of modern Croatia. One century later, in the very late part of it, western influence saw to it that Glagolitic was to be no more. The culture and the script crumbled under secular pressures from the west, and it relied solely on printed material. By the time the twentieth century had rolled around and Fascist Italy did its bit in many part of modern Croatia, the areas in which the Glagolitic script had managed to cling on to existence suffered tremendously, and these areas were scaled back even more.

Glagolitic in modern day Croatia

Many ancient buildings, such as churches, still bear the Glagolitic script to this day, and of course, items bearing it can also be purchased across the country. The brand new Croatian euro coins with national motifs on them also proudly bear this ancient script, and it can be found on the 2 and 5 cent coins minted here. The 1992 discoveries in Eastern Croatian churches also shed light on the script, and those churches are in Lovcic and Brodski Drenovac. Some of the oldest stone monuments with the Glagolitic script engraved on them have been found in Istria and on the island of Krk, and in February each year, Croatian Glagolitic Script Day is marked in an attempt to preserve the rich and rather mysterious history of this script for generations to come.

For more on the modern Croatian language, dialects, subdialects, extinct languages, and learning Croatian, make sure to check out our dedicated lifestyle section.

Az, Buki, Vidi: 5 Things to Know About the Glagolitic Alphabet

February 22nd, 2022 - In honour of the Croatian Glagolitic Script Day, we bring you five facts about the old Croatian alphabet, from medieval graffiti to the first printed Croatian book

If you’ve been to Croatia, you must have seen it someplace: the Glagolitic script, the oldest known Slavic alphabet, was used in Croatia from the Middle ages all the way to the 20th century.

The script was mostly used in liturgy and in administrative law. Linguistic experts (and enthusiasts) aside, you’d be hard pressed to find someone who can read or write the Glagolitic alphabet these days.

Nevertheless, it’s an immensely important part of our cultural heritage, deserving of its own official day that’s observed each year on February 22nd. To mark the occasion, here are five - hopefully interesting - facts:

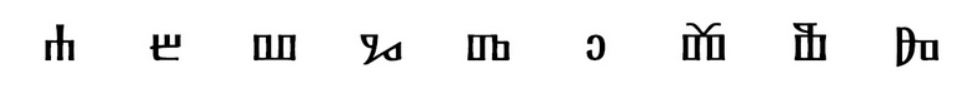

1. Each character in the Glagolitic alphabet is a letter, a word, and a numeral in one.

For example, the first letter of the Glagolitic alphabet is Ⰰ: A. It also signifies the word az, which means I. And finally, it stands for the number 1 as well.

When the characters were meant to represent numerals, they were written with the grapheme ~ at the top and dots on the sides.

It only gets better from there. String together the first nine letters of the Glagolitic alphabet, and you get an actual sentence: Az buki vidi glagole dobro est živjeti zelo zemlja. Loosely translated into English: I who know letters say that it’s good to live on Earth.

Or, in Glagolitic script:

Language is amazing.

2. Medieval worshippers were known to vandalise chapel walls with Glagolitic graffiti.

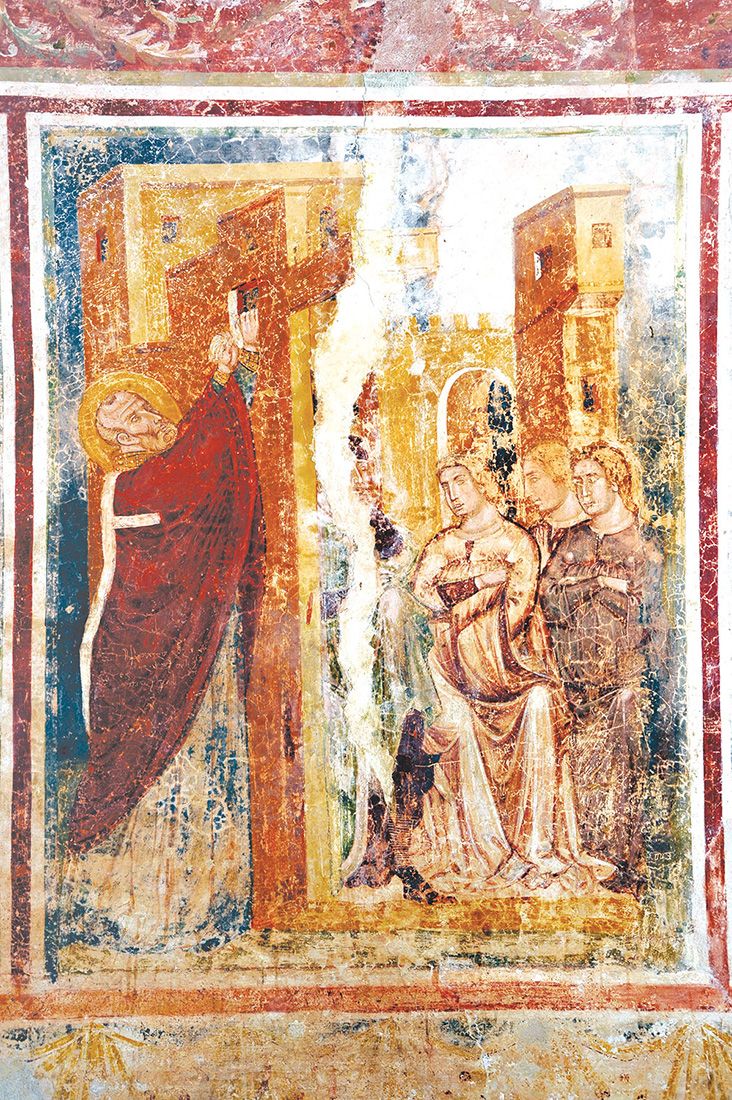

Countless medieval chapels in Istria are adorned with gorgeous frescoes, but if you take a closer look, you’ll often find small inscriptions in the Glagolitic script scratched into the surface.

Bishops and priests were prone to carving their names into the walls, so it’s no wonder that the common folk followed suit. The graffiti of medieval Istria speak of common social issues: famine, disease, poverty, war.

In the church of St Nicholas in Rakotule, on a fresco depicting St Nicholas leaving a bag of gold on the windowsill of a poor family's house, a note is scribbled: Give me a coin or two as well, Nico, so help you God.

A fresco in the church of St. Nicholas in Rakotule

A fresco in the church of St. Nicholas in Rakotule

On the other hand, not all the messages are tragic, some being more reminiscent of third-graders scribbling on classroom desks. Such as the one in the Pazin parish church, where a certain worshipper noted:

I, Ivan Fraščić, came to Pazin and wrote…

The note abruptly stops here, but someone else was kind enough to finish it:

...wrote that I'm a beast and a worthless trinket.

We really haven’t evolved much since.

Learn more about the Glagolitic graffiti in Istria in our dedicated feature.

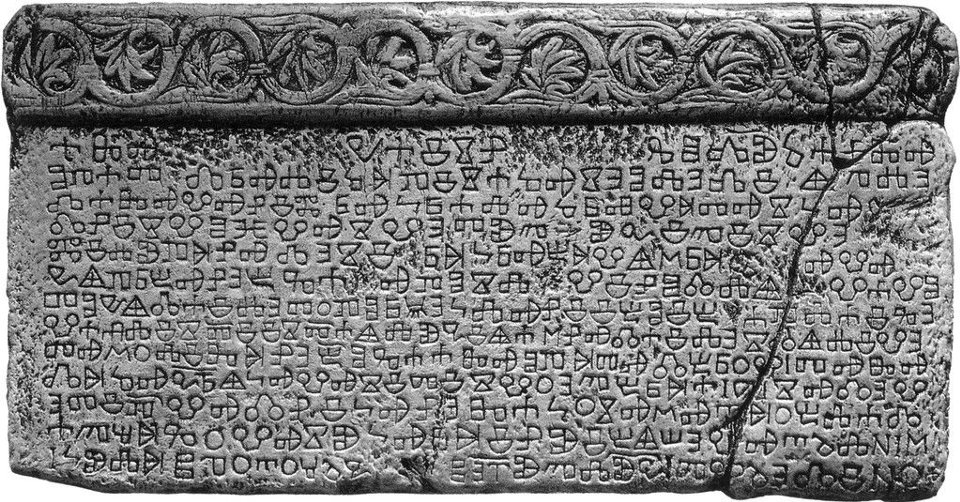

3. The first mention of the name Croatia, in Croatian, is set in stone in the Glagolitic script.

And a hefty chunk of stone at that: the Baška tablet, discovered in the church of St. Lucy on Krk island, is almost two metres wide, one metre tall, and weighs 800 kilograms.

It’s almost as if they knew that we as a nation would collectively obsess over it one day.

Dating to the early 12th century, the monument is a record of King Zvonimir’s donation of land to the Benedictine order, with the text inscribed in the massive limestone slab written in the Glagolitic script.

The crucial part of the text reads:

I, abbot Držiha, wrote this regarding the land which Zvonimir, the Croatian king, gave in his days to St. Lucy.

Further down, the abbot adds:

Whoever denies this, let him be cursed by God and the twelve apostles and the four evangelists and St. Lucy. Amen.

That’s a lot of ill fate to take on. The abbot’s claims remained undenied, and the original Baška tablet is now displayed in the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Zagreb. A replica was installed in the church of St. Lucy.

Church of St. Lucy in Jurandvor, Krk island. Replica of the Baška tablet installed as the left altar partition / Image by Roberta F, Creative Commons

Church of St. Lucy in Jurandvor, Krk island. Replica of the Baška tablet installed as the left altar partition / Image by Roberta F, Creative Commons

4. Some special exceptions were made for the Glagolitic script.

Croats were the only nation in Europe to have been granted special permission to use their own language and the Glagolitic script in liturgy instead of Latin. We love feeling special.

Pope Innocent IV first extended this courtesy to the bishop Philip of Senj in 1248. A few years later, he also allowed Benedictine monks in Omišalj on Krk island to use the Croatian Church-Slavonic liturgy and the Glagolitic script.

It’s also worth mentioning that the Senj cathedral in Croatia is the world’s only Roman Catholic cathedral where Mass was celebrated in a language other than Latin up to the 1960s, when the Second Vatican Council finally allowed the use of vernacular languages in liturgy.

Baška Glagolitic Trail, the letter A. Sculpture by Ljubo de Karina / Image by Roberta F, Creative Commons

Baška Glagolitic Trail, the letter A. Sculpture by Ljubo de Karina / Image by Roberta F, Creative Commons

5. Croatia’s first printed book came off the press on this day in 1483.

That's a long history of publishing! Seeing that it was written in the Glagolitic script, it doesn’t come as a surprise that it was a liturgical book - the only missal in Europe that wasn’t printed in the Latin script.

While the printing location remains undetermined, we know the exact date: the first copy was printed on February 22nd, 1483.

It only makes sense for the official day of the old alphabet to be observed on the very same date. It’s a relatively new occasion, as the Croatian Parliament voted for the date to be declared the Croatian Glagolitic Script Day in 2019.