Exploring Croatian - A Brief History of the Istro-Romanian Language

November the 28th, 2022 - Have you ever heard of any Balkan-Romance languages other than Romanian? Unless you happen to be a linguist, the term is probably somewhat alien to you, especially given the fact that the languages spoken across much of the region (but not all of it) are Slavic. Let's get better acquainted with the sparsely spoken Istro-Romanian language.

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian.

Istria in particular is full of culture, and its rather complex historic relationship with Italy and in particular with the formerly powerful Venice has a lot to answer for in this regard. That brings us to a language that actually has nothing to do with Venetian, and is only spoken by people who call themselves Rumeni or sometimes Rumeri. It can only now be heard in very few rather obscure locations and with less than an estimated 500 speakers of it left, the Istro-Romanian language is deemed to be seriously endangered by UNESCO's Red Book of Endangered Languages.

Who are the Istro-Romanian people?

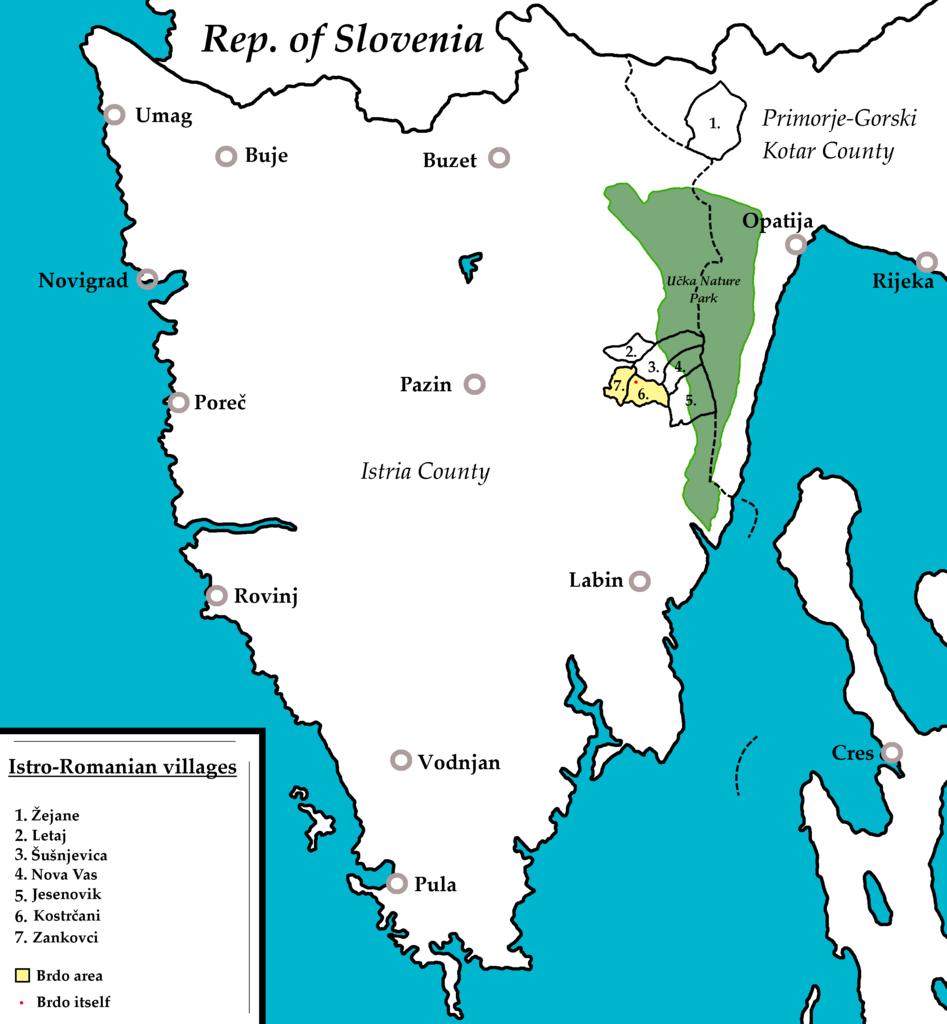

The Istro-Romanians are an ethnic group from the Istrian peninsula (but they aren't necessarily native) and they once inhabited much of it, including parts of the island of Krk. It's important to note that the term ''Istro-Romanian'' itself is a little controversial to many, and most people who identify as such do not use the term, preferring instead to use the names taken from their villages. Those hamlets and small settlements are Letaj, Zankovci, the wider Brdo area, Zeljane, Nova Vas, Jesenovik, Kostrcani and Susnjevica.

Many of them left to begin their lives in either larger Croatian cities or indeed in other countries as the industrialisation of Istria in the then Yugoslavia progressed at a rather rapid pace. Following Istrian modernisation which had enormous amounts of resources pumped into it by the state, the number of Istro-Romanian people began to dwindle rather significantly, until they could only really be found in a handful of settlements.

The origins of the Istro-Romanian people are disputed, with some claiming they came from Romania, and others claiming that they arrived originally from Serbia. Regardless, they have been present in Istria for centuries and despite efforts from both the Romanian and Croatian governments to preserve their culture and language - the Istro-Romanian people are still not classed as a national minitory under current Croatian law.

Back to the Istro-Romanian language

Like many dying languages, the Istro-Romanian language was once much more widely spoken across the Istrian peninsula, more precisely in the nothwestern parts near the Cicarija mountain range. There are two groups of speakers despite the fact that the language spoken by both is more or less absolutely identical, the Vlahi and the Cici, the former coming from the south side of the Ucka mountain, and the latter coming from the north side.

Back in 1921, when the then Italian census was being carried out, 1,644 people claimed they were speakers of the Istro-Romanian language, with that figure having been deemed to actually be around 3,000 about 5 years later. Fast forward to 1998, the number of people who could speak it was estimated to stand at a mere 170 individuals, most of them being bi or trilingual (along with Croatian and Italian).

The thing that will be sticking out like a sore thumb to anyone who knows anything about language families - the fact that this is called a Balkan-Romance language. While it is classified as such, the Istro-Romanian language has definitely seen a significant amount of influence from an array of other languages, with approximately half of the words used drawing their origins from standard Croatian as we know it today. It also draws a few from Venetian, Slovenian, Old Church Slavonic and about 25% or so from Latin.

Istro-Romanian is very similar to Romanian, and to anyone who doesn't speak either but is familiar with the sound, they could easily be confused. Both the Istro-Romanian language and Romanian itself belong to the Balkan-Romance family of languages, having initially descended from what is known as Proto-Romanian. That said, some loanwords will be obvious to anyone familiar with Dalmatian, suggesting that this ethnic group lived on the Dalmatian coast (close to the Velebit mountain range, judging by the words used) before settling in Istria.

Most of the people who belong to this ethnic group were very poor peasants and had little to no access to formal education until the 20th century, meaning that there is unfortunately very little literature in the Istro-Romanian language to be found, with the first book written entirely in it having been published way back in 1905. Never used in the media, with the number of people who speak it declining at an alarming rate and with Croatian (and indeed Italian) having swamped Istria linguistically, it's unlikely you'll ever hear it spoken. Some who belong to this ethnic group who live in the diaspora can speak it, but that is also on a downward trajectory.

This language has been described as the smallest ethnolinguistic group in all of Europe, and without a lot more effort being put into preservation, the next few decades to come will almost certainly result in the complete extinction of the Istro-Romanians and their language.

For more on the Croatian language, dialects, subdialects and history, make sure to check out our dedicated lifestyle section.

Smuggling for Survival: Contraband Trails of Učka Mountain

February 19th, 2022 - In the 1930s, villages in northeastern Istria made a living running contraband over Učka mountain from a duty-free zone on the coast. The fascinating story of smuggling for survival is just part of the local history presented in the Ecomuseum Vlaški puti in Šušnjevica

At the foothill of Učka mountain in Istria lies the village of Šušnjevica. It’s not a destination to make headlines or get a mention on a must-see list. And yet, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better place to visit if you happen to like going off the beaten path.

Šušnjevica packs so much to discover, including a history of smuggling, stories of survival, and a dying language. The many facets of this incredible little place are presented in an interpretation centre named Vlaški puti (Vlach paths), introducing visitors to the social history and cultural heritage of the area.

Clandestine activities always seem to draw the most attention, so it only makes sense to start there: the unassuming village is located in the area where illicit trade thrived in the early 20th century.

For a bit of historical context, the Italian-ruled Kvarner Province at the time encompassed the wider Rijeka area, including a chunk of Slovenian territory in the north, and all the settlements lining the Opatija riviera in the south.

In 1930, the coastal part of the province was declared a duty-free zone by the Italian government (zona franca). The economic crisis left a mark on these parts as well, development of tourism was stalled, and so the decision to abolish customs was meant to shake things up a bit and give Rijeka and Opatija an edge over other popular destinations in the Northern Adriatic.

Naturally, consumer goods suddenly became much cheaper in the duty-free zone than in the rest of the province, and the local population was nothing if not resourceful. Living conditions were tough at the time, especially in rural areas, and any opportunity to make a living was seen as more than welcome.

And so the people of Šušnjevica and other villages in the area started running contraband, smuggling inexpensive goods out of the duty-free zone. They sold their produce and poultry in seaside towns, and in turn mostly purchased sugar, coffee, textile and petroleum. The illicit goods were transported on foot over Učka mountain and resold for profit in the rest of the region.

It was a dangerous business, both in terms of scaling rugged mountain slopes and avoiding the unforgiving customs officers who monitored the area. It should be mentioned that contraband goods were not smuggled out of greed for profit, but solely to ensure survival in times of scarcity.

Učka mountain

Učka mountain

If you’re up for a hiking adventure, you can now retrace the steps of smugglers past. Three hiking trails have been established in the territory of Učka Nature Park to introduce visitors to the lively history of contraband in the area. A mobile app was launched, containing detailed information about the hiking routes, along with a list of accommodation providers and restaurants in the area. It’s available to download on GooglePlay and AppStore - look for Kontraband thematic trails.

All three are demanding routes and vary from 6 to 10 kilometres in length, but are well worth the effort - the trails are scenic, feature wonderful views, and you’ll get to see a few historic sites along the way. Among them is the abandoned village Petrebišća, a place of importance in regards to Slavic mythology. Another stop commemorates a young smuggler who tragically died aged 12 when he got struck by lightning on Učka mountain; following his death, every smuggler in passing would lay a stone at the memorial site, which in time grew into a massive pile of stone, the so-called gromača.

The shortest trail (KB1) starts in Šušnjevica, and those who opt to take this route should really use the opportunity to discover more about this fascinating place at the Ecomuseum Vlaški Puti.

Director of the interpretation centre Viviana Brkarić is more than familiar with the subject, having had family members who dealt in the contraband trade. Viviana speaks of her grandmother, born in 1901; times were tough, she had to support her family, and was known to make the trip to the duty-free zone and back 3-4 times a week. She’d occasionally get caught smuggling goods over Učka which landed her in prison, but she didn’t mind as it meant ‘she’d get to rest for a while’.

The prison guards soon realised she knew how to sew, and would have her sew clothes and mend bedding. According to Viviana, grandma didn’t mind as they treated her as a guest and gave her better food than to an average prisoner. Apparently, the guards were quite happy to see it was her every time she was apprehended, and were known to say ‘she’s here, she’ll now mend everything that needs mending’. (Agroklub/Blanka Kufner)

These days, Šušnjevica is home to about 70 people, most of whom are Istro-Romanian in origin and are some of the last living speakers of Vlashki (vlaški), one of the two existing varieties of the Istro-Romanian language. The other variety is called Zheyanski (žejanski) and is spoken in the Žejane area on the northern side of Učka mountain.

Once spoken in a much larger part of northeastern Istria, Istro-Romanian is now listed as ‘severely endangered’ in the UNESCO Red Book of Endangered Languages, and is inscribed in the list of protected intangible cultural heritage of Croatia. In the mid-20th century, the language was reportedly spoken by up to 1500 people, but the numbers dwindled as the harsh living conditions drove people to move to bigger urban areas in the country or emigrate to the US and Australia.

Interestingly, nowadays there are more native speakers of Istro-Romanian living in New York than in Croatia. It’s estimated there’s a community of some 300 people keeping the language alive in the diaspora, whereas the latest count from 2019 put the number of Vlashki speakers in Croatia at about 70.

The language is not passed from generation to generation anymore, and so the youngest people who actively speak Vlashki are about 50 years old.

Preserving this priceless heritage for future generations is one of the goals of the ecomuseum. The interpretation centre is designed to introduce visitors to the local history and traditions, while the media library contains materials in Vlashki and Zheyanski languages, as well as digitised publications about the language and other topics of regional importance.

Website: Ecomuseum Vlaški puti

Working hours: Monday to Saturday, 10 AM - 2 PM

Oxford University Invites Speakers of Istro-Romanian to Join Research Project

ZAGREB, 13 Aug 2021 - Researchers from the Oxford University Faculty of Linguistics, Philology and Phonetics have invited the remaining speakers of the severely endangered Istro-Romanian language to help them translate and understand the collected audio recordings of that language in a project called ISTROX.

This interdisciplinary project was launched in 2018 and is based on sound recordings made in the 1960s by Oxford linguist Tony Hurren during field research in the areas of Croatia where Istro-Romanian is spoken. The recordings were donated to the Taylor Institution Library in Oxford.

During the first stage of the project, the audio recordings were described in detail and catalogued, and the content of Hurren's notebooks was matched to the recordings. In the second phase, the less intelligible recordings were uploaded on the citizen science web portal Zooniverse.

The remaining speakers of Istro-Romanian who live in Croatia and those who live abroad have been invited to register with the platform and help researchers clarify the problematic linguistic elements.

All of the data resulting from the research and all other materials that are currently part of the Hurren donation will be uploaded on the Internet to make them available to the scientific community and public, the ISTROX research team has said.

This material has never been published, and its existence has hitherto been virtually unknown to the wider world. Hurren used it for his doctoral thesis.

"The recordings, which include folktales, accounts of local traditions, and autobiographical remarks and stories, are not just of crucial interest to linguists, but also contain unique documentation of the history of the community that spoke, and still speaks, the language," the researchers said.

Hurren worked with a large representative sample of speakers of all ages and covered nearly all the villages in which Istro-Romanian was spoken, thereby capturing material for a description of the major linguistic subdivisions (there are two major dialects), the researchers said.

Istro-Romanian is possibly the least-known of the surviving Romance languages and its phonology, morphology, syntax, and lexicon are of enormous interest to linguists generally, and to Romance linguists in particular, the researchers said.

Istro-Romanian is a Romance language and is historically descended from the Latin of the Roman Empire. The language is most closely related to the one surviving major Romance language of Eastern Europe, namely Romanian.

It is one of four major branches of what linguists call 'Daco-Romance', which refers to the surviving Romance (Latin-based) languages of south-eastern Europe, continuing the Latin assumed to have been spoken in the Roman province of Dacia.

It is not known when exactly Istro-Romanian broke away from the ancestor of modern Romanian, but the separation may go back as much as a thousand years.

The place of origin of the language, and the question whether it branched off from varieties spoken in Romania or from other varieties spoken in the Balkans, or whether it represents a dialect mixture, are still controversial.

The language is still spoken in Žejane, northwest of Rijeka, and around the village of Šušnjevica on the western slopes of Mt Učka in Istria. The speakers in Žejane call the language Žejanski and those in Istrian villages call it Vlaški. An estimated 250 inhabitants of those villages are believed to still speak that language as do those who emigrated to bigger cities or abroad.

The Croatian Culture Ministry in 2007 included Istro-Romanian on its list of protected intangible cultural heritages.

Those who speak or understand Istro-Romanian can help preserve a record of this disappearing language by going to www.istrox.uk. More info about the project: https://istrox.ling-phil.ox.ac.uk/. Both platforms are bilingual (English and Croatian).

Istriot, Arbanasi, Istro-Romanian: 3 Dying Languages in Croatia, Just 1200 Speakers

December 28, 2019 - Croatia regularly makes top 20 lists around the world, from football to tourism. But did you know is it is also in the top 20 list of most endangered languages no less than 3 times? Meet Istriot, Arbanasi and Istro-Romanian, spoken by just 1200 people combined.

It is a sad reality that many traditions and much cultural heritage is dying out around the world, as the traditions of the older generations are embraced less and less by the younger generations in this modern, digital era. Among the things being lost is language. Globalisation has played its part in the rise of languages such as English, while at the same time local languages are not taken up as much by the young, and so many languages have become extinct. Indeed today there are some 7,111 languages around the world, but just 23 languages account for half of the world's population, and some 40% of languages today are endangered, many with less than 1,000 native speakers remaining.

On the list of the most critically endangered, I was surprised to find which country featured the most - Croatia. No less than three languages spoken in Croatia which are in danger of extinction - Istriot, Arbanasi and Istro-Romanian. While I had heard of Istro-Romanian (why else would the world's first vampire, Jure Grande, come from Istria...), the other two were new to me, and I decided to look into things with a little research.

And this being the Balkans, baby, it didn't take me long to learn that Nikola Tesla was not a Serb at all apparently, but had Romanian roots and was an Istro-Romanian speaker... But let's not veer off topic.

Let's begin with Istriot.

Istriot is a Romance language spoken by about 400 people in the southwestern part of the Istrian peninsula in Croatia, particularly in Rovinj and Vodnjan. It should not be confused with the Istrian dialect of the Venetian language. It is a Romance language related to the Ladin populations of the Alps. Its exact classification has long been unclear, but in 2017, the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History with the Dalmatian language in the Dalmatian Romance subgroup.

Historically, its speakers never referred to it as "Istriot"; it had six names after the six towns where it was spoken. In Vodnjan it was named "Bumbaro", in Bale "Vallese", in Rovinj "Rovignese", in Šišan "Sissanese", in Fažana "Fasanese" and in Galižana "Gallesanese". The term Istriot was coined by the 19th-century Italian linguist Graziadio Isaia Ascoli.

Similiar in the geography of its speakers is Istro-Romanian, a Balkan Romance language, which is still spoken in a few villages and hamlets on the Istrian peninsula. While its speakers call themselves Rumeri, Rumeni, they are also known as Vlachs, Rumunski, Ćići and Ćiribiri. The last two, used by ethnic Croats, originated as a disparaging nickname for the language, rather than its speakers.

And could it be that the most famous speaker of Istro-Romanian was the most famous inventor of them all? Romanian inventor Henri Coanda seemed to think so...

a scientist who was personally acquainted with Tesla, said he had a neo-Latin appearance and did not looked like a slav (in fact Nicola Tesla in the picture above looks like a typical Venetian citizen, as many I have known myself with very similar appearance in the Veneto). Coanda even wrote that Tesla spoke in "Istro-Romanian": I invite the reader to read http://istro-romanian.com/news/1999_0111tesla-rom.htm (unfortunately in Romanian) about this language knowledge. How could Nicola Tesla speak a language (the Istro-Romanian) that was not taught in school in those years and that was only spoken by a few thousands people in Istria and in nearby Lika? Of course, only if he had learned it from his family as a child.

Moving further down the coast to Zadar and a third endangered language, whose roots are Albanian via Montenegro - Arbanasi.

Originally Albanian Catholics from Skhoder in northern Albania, the Arbanasi fled to Croatia with the help of the Archbishop of Bar between 1726 and 1733, eventually setting in the Zadar region, where they have remained ever since. They no longer see themselves as Albanians, but as Arbanas Croatians.

Due to the fact that there has been a long history of interaction with other tribes and nations, there are many external influences on the Arbanasi language today. Originally based on a unique Gheg Albanian dialect, the years have embraced influences from Croatian, Italian and Venetian, and there are many loan words in the language today. Additionally, a large number of Chakavian speakers settled among them and left their influence. Back in 2016, an initiative was launched to keep Arbanasi alive in one school in Zadar.

Are you a speaker of Istriot, Arbanasi or Istro-Romanian? We would love to hear from you and feature your story and language in more detail on TCN. Contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Subject Rare language.

But perhaps there is something even linguistically rarer than these three languages in Croatia - foreigners who speak Croatian well. A look at 25 of the most common mistakes foreigners make when learning Croatian.