Changing History: Which Innovations Had Make or Break Impact on Nations and Societies?

Interview with Mirko Sardelić, Ph.D, Research Associate at the Department of Historical Studies HAZU, Honorary Research Fellow of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions (Europe 1100-1800) at The University of Western Australia; formerly a visiting scholar at the universities of Cambridge, Paris (Sorbonne), Columbia, and Harvard.

Intro: The human species has a unique capacity in terms of abstract thinking and innovation. Our civilization has advanced as humans developed new creations. Now, we are living in times when the speed of innovation is faster than ever, when the reach and the adoption of every new technology is quicker and wider than ever before. Still, on the one hand we have small but very innovative countries; on the other hand, some countries are quite big in terms of size and highly populated, but still falling behind. In this interview, we will discuss which technologies and discoveries changed the course of history and the balance between societies and countries.

Q1: What were the first discoveries that happened at the dawn of our civilization? How long did it take for them to spread around the globe?

From today’s perspective when we think about technology, the things that come to our mind are often connected to electronics, robotics, or nanotechnology. But in order to get to these advancements, some simple yet fantastic discoveries shaped the way humans made the environment much more hospitable, or safer. If a community wanted to protect itself, its members needed fortifications such as walls and fortresses. If they wanted the fortifications to pose a serios obstacle, they made them of big blocks of stone; and this was not just in ancient times. How does one transport these huge blocks much easier? By rolling them on tree trunks, forming slides of some sorts, with humans or animals pulling ropes. Tree trunks are round, they roll nicely across the terrain; and if you cut just a piece of a cylinder, you get something which can be called a wheel. Four kinds of independent evidence for the use of wheel for wagons appeared across the ancient world between 3400 and 3000 BCE. The wheel has had an enormous impact in human history; however, there were some advanced civilizations, such as the ones in South America, that did not use it.

One tends to overlook the importance of the screw, the last of simple technologies invented, some 3000 years ago in Mesopotamia. Just check out modern machinery and you will see how bolts and screws keep those machines together. In Mesopotamia and ancient Greece screw pumps were used for irrigation, i.e. to transport water. One can also mention nails, a simple and yet a very important element that binds things together.

In terms of processes that are more complex, I believe that the development of metallurgy had a huge impact on these later stages of human evolution – it got us out from the Stone Age anyway. In order to be able to shape bronze, humans first needed to develop the technology of furnaces capable of maintaining the temperature around 1000 C. Arguably the oldest Bronze Age cultures were in the Balkans, around the Danube basin, some 6000 years ago. Bronze was a great asset when it comes to making tools and weapons. Bronze weapons were crucial in combat – many wars were won just thanks to this improvement. Around 1700 BC the people from western Asia called Hyksos used their bronze weaponry and chariots to conquer not just any kingdom, but the grand Egypt whose infantry was fighting the war while equipped with copper swords.

As far as the circulation of these inventions is concerned, resources of information, innovations and techniques accumulated in each region sooner or later found their way throughout the Afro-Eurasian zone. The exchange and transfer of knowledge in this vast continental mass was quite intense; however, it took up to several centuries for some technologies to get introduced to various places during the Metal Ages. Conversely, three other inhabited continents were left out of this flux.

Q2. Was there a discovery that helped our civilization to mature and form the concepts that we see today – countries and nations?

This is quite a broad aspect. Let us begin with agriculture and domestication of animals that are closely connected with sedentary cultures. Farmers started planting grains some 10-12.000 years ago, and not much later (probably some 10.000 years ago), sheep, pigs and cattle commenced their cohabitation with humans. Food surpluses allowed the creation of the first cities, in Mesopotamia and South Anatolia, before 7000 BCE. Requisites for agriculture were favourable climate and access to water; the latter was acquired through, among other means, irrigation, another great invention. In river valleys and swampy terrains of Egypt or Southeast Asia one could use digging sticks to create seed drills, but harder soil craved for the invention of ploughs.

Cities became centres of economic, political, and religious activity. Let us just remind ourselves that 55% of the world’s population today lives in urban areas, which is projected to be close to 70% by 2050.

As for spiritual activity, Christian and Buddhist societies of the Eurasian continent experienced the important invention of the monastic life. An order of men detached from quotidian social connections, eminently mobile, dedicated their life to specialization in the highest intellectual or spiritual discoveries that contributed significantly to their societies.

Nations are imagined political communities, mostly formed in the 19th century for various reasons; mostly aiming political stability that ensures all other activities to develop in what is perceived a safer, more homogenous environment. In principle, the institutions of national governments are trusted with nation’s defence, education, legislation, civil rights, foreign relations, transport infrastructure, and a whole set of tangible and intangible structures that enable complex social activities.

Q3. What were the main historical discoveries and innovations that started new epochs of development?

The first that comes to my mind is the one that marks the beginning of history: the invention of writing. It was invented in several different places independently, first in Mesopotamia and Egypt (ca 3200 BC), then in China (1500 BC) and Mesoamerican cultures. In the beginning, it was used mostly to record the most important information related to agriculture or taxation, but later on it developed into an indispensable tool to transfer ideas; in short, this included anything worth remembering and developing. Manuscripts were circulated across the Afro-Eurasian world for centuries, contributing to development of ideas and technologies. Writing is the embodiment of ideas, but it is much more than that: it has a cognitive and social function. Therefore, we all continuously practice writing, we contemplate, polish, and revise our texts, i.e. our ideas.

Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century made the written word the medium of mass communication and removed some limitations for the circulation of information. Books became more accessible, and more numerous: it is estimated that by the year 1600 some 200 million copies of various books were printed. One can only imagine how many more books eventually were printed over the four centuries that followed. A subsequent medium that appeared in the 17th century, the newspapers, shaped the world of information in the way that Internet and TV shape digital circulation today.

Q4. What technologies made the biggest changes in relations between the countries or continents, or changed their power relations?

The 18th century saw the invention of the steam engine. Its improvements in the 19th century gave birth to machines, which resulted in enormous advancements in industry, transportation, and agriculture. In turn, this gave base to the rise of superpowers such as Great Britain and the United States of America. High-pressure engines started setting ships, trains, cars, and eventually airplanes in motion. Steam engines powered the Industrial Revolution that shaped the world as we know it today.

Q5. With the development of new weapons, in the 21st century, the old ones are becoming increasingly obsolete. Tanks dominated in the last 100 years but are now becoming useless, mostly because of much cheaper drones. Was there a discovery or technology that empowered one country in war or a similar kind of conflict?

In one of our previous interviews, we mentioned that one who wants to win the war needs two requisites (to start with): the means to finance it and good logistics. In the present day, the development of new weapon technologies is more entangled with the financing of new ideas and related discoveries. But in the past, some very simple ideas lead to the creation of extremely powerful military units. Again, somewhat neglected from a modern perspective, chariots were a high-tech weapon some 3000 years ago. It is not directly connected to technology, but it is hard to overemphasize the importance of horses on warfare through at least four millennia of human history. Alright, some inventions such as the stirrup or the saddle made them more effective over time. Cavalry was a predominant force until the invention of reliable, fast, and powerful weapons at the beginning of the 20th century. For centuries European armies had difficulties confronting Eurasian nomads (the Huns, Magyars, Cumans, Mongols…) whose light cavalry used (composite) bows to launch thousands and thousands of arrows in a matter of minutes. Even one of the most successful military formations of ancient times, the Macedonian phalanx, needed cavalry on its flanks despite its 5-meter-long spears.

Composite bows and longbows were the light artillery for millennia. The mentioned steppe nomads dominated battlefields of Eurasia using exactly those kinds of weapons. English longbows were the equivalent in Western Europe in the Late Middle Ages (12th-15th centuries). Its ‘mechanic’ cousin, the crossbow, was so powerful and lethal that Pope Innocent II (1139) forbids its use against Christians.

Great wars of the 20th century significantly improved the weaponry, created nuclear powers and lead to the development of rocketry.

Q6. It is expected that much of the future warfare will be cyberwar. Many countries are developing their cybersecurity as a response. Has something similar to that process happened in history?

Technology made everything more accessible, which means not only physical protection is needed, but virtual protection has increasingly gained importance. One can use your credit card from another continent, skilful hackers can turn off the electricity to a block or even part of some remote town. It is a perennial question of access to information and those skilful enough to (ab)use it.

One of my main interests are nomadic empires, so I will draw two examples from the rise of the Mongols. Once they had established the empire, they realized that they should use all skilled workers they encountered and captured in their campaigns. The Chinese had very capable engineers who could build impressive structures or produce war-machines, the Persians had experienced administrators (…) – all those were used to do the things nomadic peoples were inexperienced in. I believe this is a great example of being aware of one’s own limitations and knowing exactly who is the most apt to compensate for those.

Also, one of the most reliable allies of the Mongol army commanders was intelligence. During the Black Sea campaigns, the Mongols gained precious information from traders (mostly Venetian) on European geography, armies, castles, population, the relations between rulers, supplies, and everything else useful on a campaign. Therefore, when they invaded Eastern and Central Europe in 1241/42, they knew exactly where to go, what to do, whom to attack or avoid, what the most vulnerable points were. The result was that they crushed several very strong European armies, pillaged several countries, and made them pay tribute.

Q7. What were, in general, the most fruitful areas of influence, where we can observe overwhelming changes? Was it in transportation, in weapons, communication, knowledge management, construction, energy, medicine, economy? And can we single out one or two dominant areas?

The Romans had exquisite mastery of construction: just take a look at their buildings all around the Mediterranean basin and beyond. It was as late as the early 20th century when the construction improved significantly. For example, the formula for Roman concrete is still sought for: its durability, resilience to saltwater, and longevity have not been surpassed to this day. All major civilizations were aware of the importance of roads and communication. On the other hand, the concept of economy is quite complex: even the best experts have troubles predicting many aspects of its development.

I could single out the change that happened to humankind with the invention of electricity. Also, the Internet contributed to unimaginable access to all sorts of information and dissemination of knowledge. Last, but certainly not the least, medical advancements need to be mentioned. Ancient civilizations had quite capable physicians. I remember a note from Greek historian Herodotus (5th ct. BC) in which he gives an account, and was quite surprised, that the Egyptians had doctors who were specialized for eyes, internal organs, etc. – just as we have today. The Chinese have had quite rich tradition in medicine as well. But what the field has achieved so far, with personalized medicine and with all the technology at our disposal, is just to become even more impressive. After all, the fear of non-existing (even of just being ill) is one of the most potent incentives known to humankind.

Q8. Today we have polarization between the USA and China, and the EU in some segments regarding technology innovations. Was there a country that was famous as a technology leader or an expert in one field?

Throughout its rich history, China was well-known for its innovations. The compass (12th ct.) made the oceans a less hostile environment, the paper money (11th ct.) made the trade and financial transactions easier, while the invention of gunpowder (11 ct.) changed the warfare of the second millennium AD. Of course, it is only through the transfer of knowledge in the late Middle Ages that most of these inventions got improved – e.g. the Venetian and Genoese merchants made significant strides to advance the financial instruments invented either by the Chinese or by the merchants in the Islamic world; gunpowder-based weaponry, such as cannons and rifles, were also improved across Eurasian continent.

In ancient times the civilization that lived in Mesopotamia was famous for its inventions. We have mentioned some: the wheel, cities, writing. However, there were dozens more, such as administration, accounting, mathematics, astronomy, sailing, production of bricks, cartography, and maybe the most interesting one: the concept of time. Based on their sexagesimal system, our hours have 60 minutes which are subdivided in 60-second intervals.

Q9. Most importantly, what can we learn from those who missed opportunities and didn't advance on time? Which civilizations collapsed or became irrelevant? What can we advise modern states, and warn them if they miss current opportunities in AI development, genetics, or any new technology that will emerge soon? Our time to react is getting shorter, and the consequences are getting bigger.

The rise and fall of civilizations were in focus of historians for many centuries. They happened mostly as a combination of several factors: ecological, economic, social, technological, richness or depletion of crucial resources such as timber, oil, or ore deposits. The system of nation-states is arguably the invention of the 19th century, and it is the best humankind has available for the moment.

One can conquer a land with a military machine, but one of the things that might have changed the world, even more, is a relatively simple invention: private property. Indigenous peoples of Australia, the Americas or Africa, who considered themselves guardians of the land they lived on, were deprived of the space they took care of. It certainly was one of the game-changers in the evolution of humankind. History gives many examples of those who were not resilient enough, not sufficiently developed or just different in terms of economy, social organisation, or technology; in the end, they no longer exist. Or at least, their way of life no longer exists. Does that mean we need to be constantly alert and improve so we do not get surpassed by rivals, or should we redefine our existence altogether? This is our dilemma. (Certainly, for a long period of history we needed the former.)

The proper globalization that started in the 20th century has demonstrated how entangled all the aforementioned factors can be. We have all witnessed what small yet provident nations such as Singapore or Norway are capable of. We are all witnessing how China has managed to multiply its industrial and financial output although it seemed that technologically it was quite behind some superpowers in the domain, only a few decades ago.

In the 21st century technological advancements in biomedicine, nanotechnology, rocketry, the AI (…) will enable people to create fabulous things. Already now pretty much anything can be produced; it is just a matter of how much money and effort is invested. There are two key questions: ‘What are we interested in?’ and ‘Who are we?’ And here I refer to a nation-state, a multinational corporation, an elite of some kind, a group of conscious individuals. As ever, it will be a combination of factors, but it seems that the least problem will be inventions of new technologies. There will be new battlegrounds of the political, social, and ethical challenges trying to answer the questions how to use the technology, and how accessible it will be.

Finally, I believe you are painfully right about the reaction time, the pressures, and the consequences. Most of us receive in one day the amount of information a single person in the Renaissance (just 15 generations ago) received during their lifetime. Shall we succumb to all sorts of internal and environmental pressures? The paradox is that humans can be very fragile, yet highly resilient. With everything happening so fast and with so much at stake, we all need to learn new things, learn more, and, as ever, adapt to crucial changes in our environment.

More interviews with Mirko by Aco on TCN:

Mirko Sardelic PhD: A Brief History of the Most Devastating Earthquakes

Mirko Sardelic PhD Interview: History of Pandemics: Lessons to Apply to Corona Crisis

Mirko Sardelic PhD: A Brief History of the Most Devastating Earthquakes

April 30, 2020 - Last month, Mirko Sardelic PhD gave an excellent interview for TCN - A History of Pandemics: Lessons to Apply to the Corona Crisis. Today, a brief history of the most devastating earthquakes.

Interviewer: Aco Momcilović, psychologist, EMBA, Owner of FutureHR

Interview with Mirko Sardelić, Ph.D., Research Associate at the Department of Historical Studies HAZU, Honorary Research Fellow of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions (Europe 1100-1800) at The University of Western Australia; formerly a visiting scholar at the universities of Cambridge, Paris (Sorbonne), Columbia, and Harvard.

In the aftermath of the Zagreb 2020 earthquake, many questions have arisen, and to answer some of them I again turned to history experts. It seems that earthquakes claimed millions of lives only in the last 100 years, and surprisingly unlike in many other areas, improvements in technology “have only slightly reduced the death toll”. They are dispersed around the world in critical areas, and they did force us to build in a smarter way. In the past, we attributed their causes to many different things, and today we have much clearer scientific information about their origins, yet, it seems they still make us feel helpless. How did our ancestors deal with all those questions? Hopefully, we will get some answers in my interview with Mirko Sardelić.

What were the strongest earthquakes in the Balkan region that history can remember?

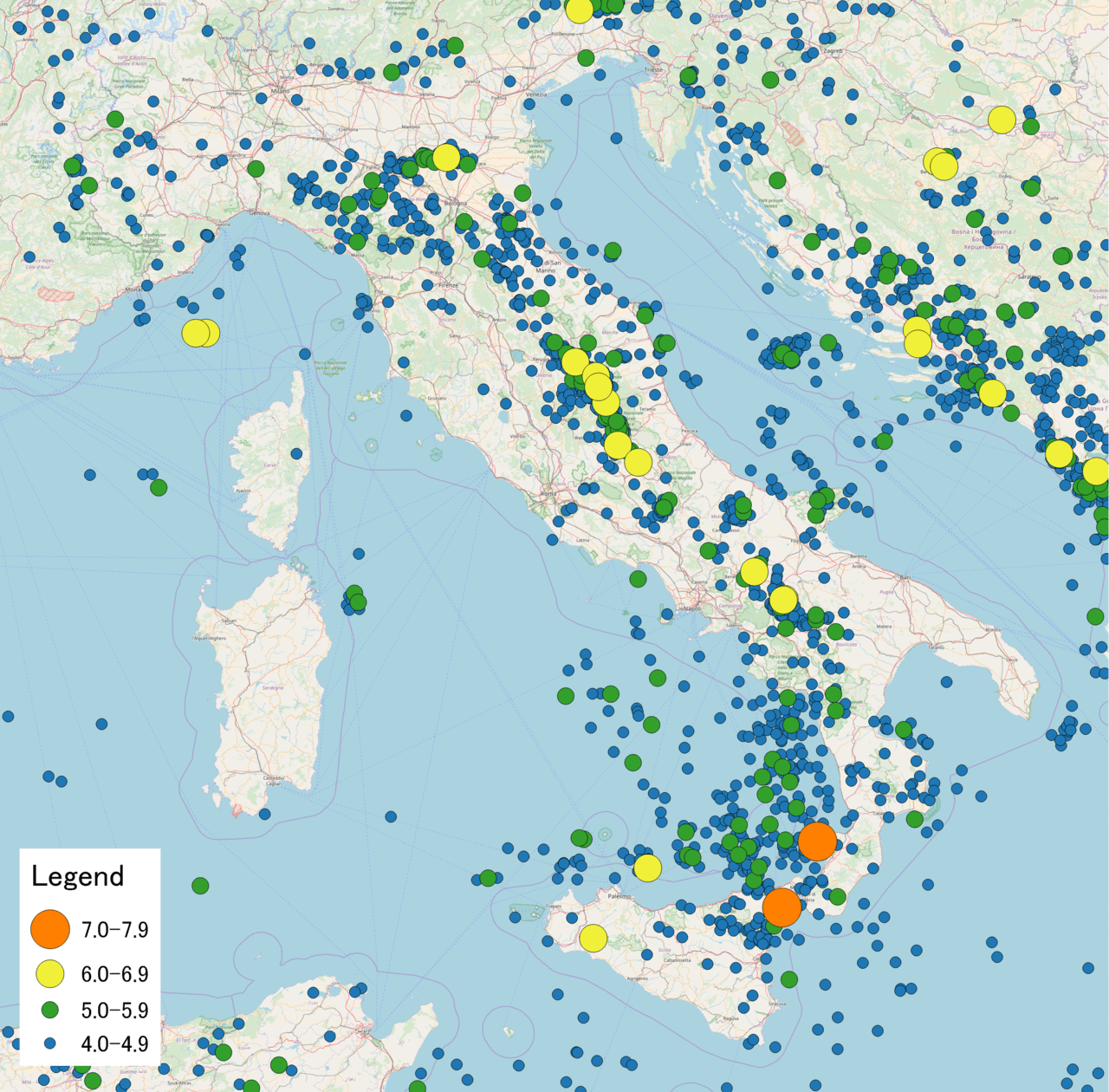

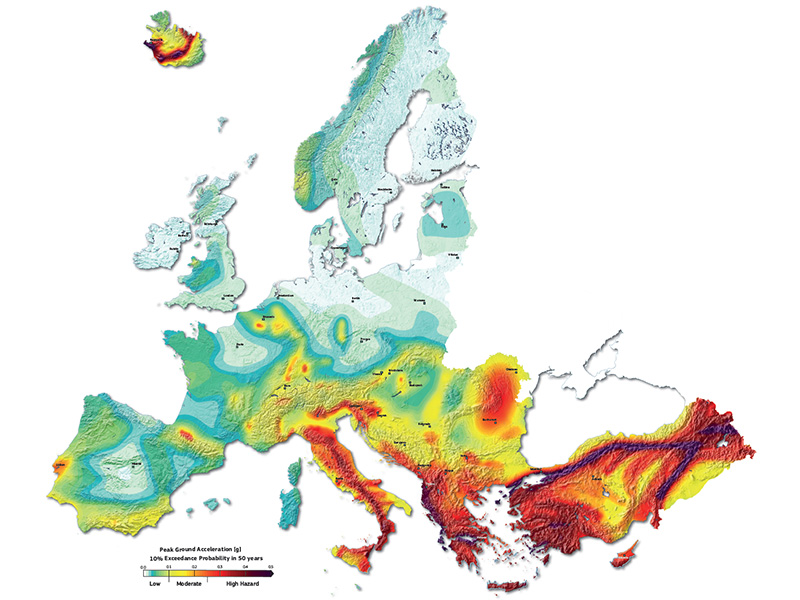

When it comes to earthquakes, the most powerful ones, higher than 7 (even 8) of magnitude, were recorded in Greece, especially Crete. Greece also has the highest number of strong earthquakes in our region. It is enough to mention the Thera (the island of Santorini) earthquake of 1500 BC and eruption that changed the history of Minoan civilization. When compared to other world regions, it can be said that the Greek quakes are quite moderate in terms of human casualties, numbering hundreds, rarely thousands. In relatively recent history, when it comes to changing the way earthquakes were perceived in former Yugoslavia, the milestone was the Skopje earthquake (6.1 of magnitude, causing more than 1000 deaths) from the summer of 1963. It has lifted the construction standards in the region significantly. Quite destructive was the Montenegro earthquake of 1979 (over 7 in magnitude) which left its mark on the architecture of Montenegro, Albania, and South Croatia.

It needs to be mentioned here that in our vicinity Italy has the most horrifying history of earthquakes. The most devastating one was the 1908 Messina earthquake that killed almost 100.000 people, razing the cities of Messina and Reggio Calabria. In the Richter scale, it was 7.1 in magnitude, however, on the Mercalli intensity scale, it was the level XI (Extreme) of destruction. Most of these earthquakes happen along the ‘spine’ of the Italian Boot, and especially in the Tyrrhenian sea between the tip and Sicily. Every several years Italy experiences quake higher than 6.0 in magnitude, the most recent ones being the Umbria one in October 2016 (6.6 in magnitude) and the Lazio/Umbria quake in August 2016 (6.2 in magnitude).

The Zagreb earthquake of 22 March 2020 was a 5.4 in magnitude on the Richter scale and VII (Very strong) on the Modified Mercalli intensity scale. Although the number alone (5.4) does not suggest terrible consequences, the hit wave had quite a strong impact on the historical city center. Late 19th century buildings didn’t handle the shock well and thousands of buildings in the heart of the city have been declared as inhabitable.

One of the two most terrible earthquakes in Croatian history was the Huge shake of 1667 that almost destroyed Dubrovnik. The city lies in the seismically most active part of Croatia and it is the most vulnerable in that aspect. The Quake was qualified as X (Very Strong) on the Mercalli scale. It killed more than 5.000 people and a big fire that raged for days followed. Also, the tsunami badly damaged the port and flooded parts of the city. The only two buildings that did not collapse were two palaces: The Sponza and the Rector Palace.

Several contemporary reports depict the horrifying situation just after the quake. One of these is the 20-canto epic Dubrovnik ponovljen (Dubrovnik rebuilt) by Jaketa Palmotić Dionorić, Dubrovnik envoy to Turkey, who lost his wife and four children to the earthquake. The letters of Frano Bobali offer a quite vivid and dramatic reconstruction of some events that followed. The Rector (mayor) of the city, alongside several governing officials, were killed, so the subsequent state of anarchy produced some nasty human-made trouble to town, such as shameless pillaging of both the rich and poor. This was, in fact, a whole package of sorrow, caused by both natural elements and humans. The fire and the dust from collapsing buildings made it a living hell for the inhabitants of the city who even thought of completely abandoning the place and establishing a brand-new town. Luckily, they had decided to stay and rebuild the city in a baroque fashion which has become world-famous for its beauty.

Do we have any data about the world’s most devastating earthquakes? How serious were their consequences, considering the number of people, and the differences in the complexity of architecture/engineering?

I am a big fan of desk globes. They are colorful, shiny, and give you an impression you understand the world. They mislead in another way: just by looking at them, one can not even imagine how fast the planet travels around the Sun (107.000 km/h) and rotates around its axis (1600 km/h). Beneath the surface there is no less action: tectonic plates collide, form trenches, layers break, magma fills the cracks; all those fuming and sizzling sounds, fortunately, remain unheard.

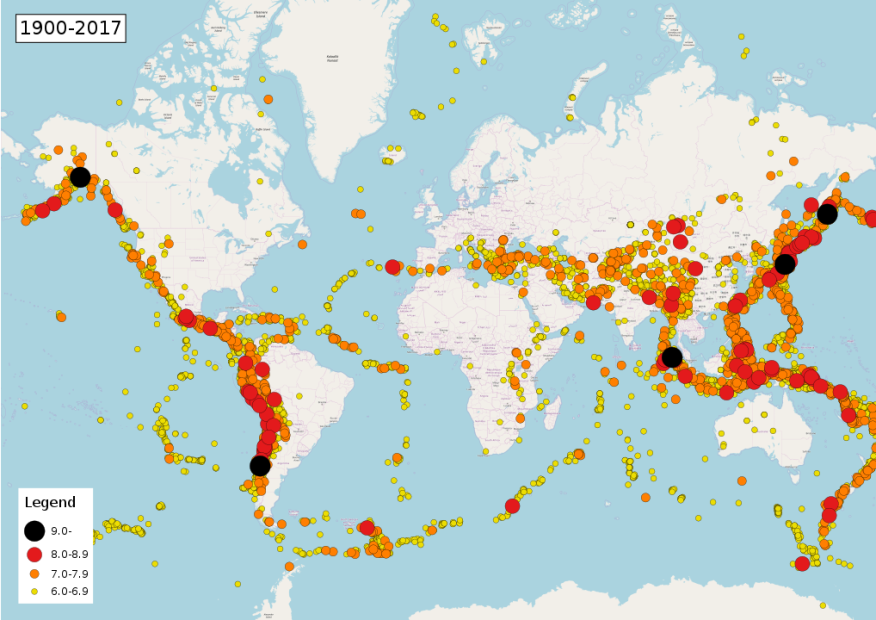

There are several scales that express the energy of the earthquake in numerical values – the most famous (albeit outdated) one being the Richter scale – developed upon the research made by Charles F. Richter and Beno Gutenberg. The numbers give quite precise ideas of how strong an earthquake is; nonetheless, the impact of each earthquake depends on several factors combined. The modern records show that the most powerful quake was a 9.5 magnitude earthquake in Chile (Valdivia) in 1960. The quake and the tsunami that followed killed some 6.000 people combined.

Some of the most horrible quakes – in terms of human victims – were recorded in Asia, which is the most vulnerable if we consider geology and population density factors combined. The Kanto earthquake in Japan (in 1923, magnitude 7.9) killed close to 150.000 people. A very powerful earthquake of Sumatra (in 2004, magnitude 9.1) killed 230.000 people and displaced close to 2 million people. The earthquake of Tangshan, China (in 1976, magnitude 7.5) killed more than 300.000 thousand people, making it one of the top three deadliest in human history. From the data, it is obvious that it is not all about the magnitude. Like the high body temperature, it indicates that there is a disturbance, but does not offer the full picture of the impact.

Since humans up until recently didn’t have the science to explain the causes of the earthquakes, to what forces were they attributed to? What are the most interesting fables created in connection with the earthquakes?

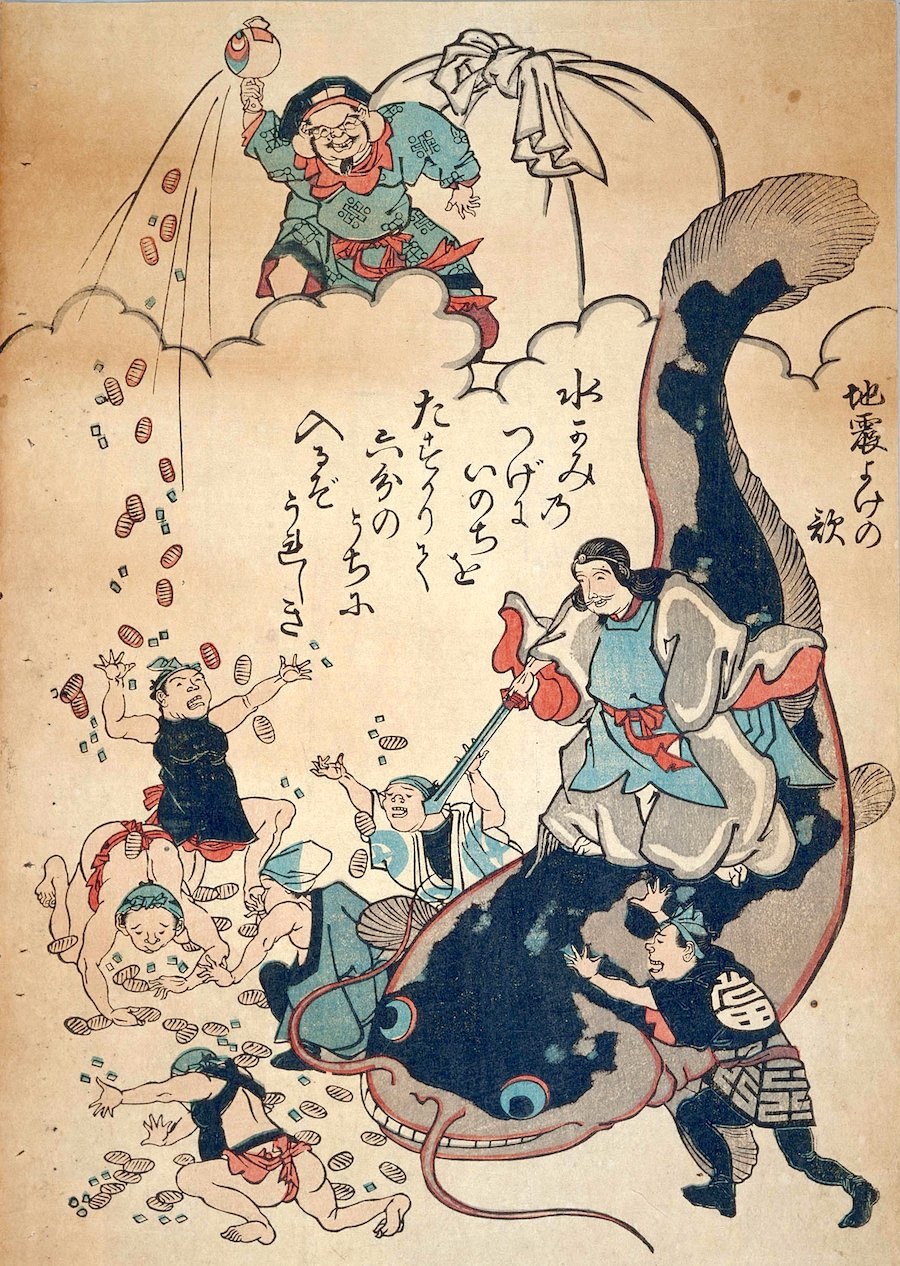

In Greek mythology, Zeus is arguably the omnipresent god, but when it comes to the earth and the sea most of the action was attributed to Poseidon, nicknamed the Earth-shaker. With his trident, he could provoke quakes that could destroy city walls, or just make the cliffs crack sufficiently enough to make a lovely spring appear in the landscape. Legend has it that when Nordic trickster god Loki starts trembling due to the snake venom that drops on his face, humans feel that as an earthquake. Traditional Japanese culture blamed the monster catfish named Namazu for causing their earthquakes by trembling. God named Kashima, therefore, holds the catfish down with a huge stone. (One of the possible explanations of the myth is that fish, like birds, can detect the tremor and subtle early signs of the incoming quake).

There are many animals involved in historical world depictions of different cultures. Animals’ movement, for one reason or another, is known to explain the origins of quakes. For example, in Hindu cosmology there are four elephants on the back of a turtle that stands on the snake and they all support the world. On the other hand, in East African legends, there is a giant fish that carries a cow on its back; the cow balances the Earth on its horns, and earthquakes happen when the cow occasionally moves the Earth from one horn to another, because of its aching neck. In the far Northeast, Siberian god Tuli carries the world on his dog-pulled sleds. When the dogs who have fleas stop to scratch, the Earth shakes.

In Maya mythology, gods destroyed the first two generations of people through a flood, and the third through the hurricane and the earthquake. On a related note, do you know that the Australian natives ‘sing the landscape’? – They connect their special places and journeys in song cycles. By singing and incorporating them into geocultural maps they can navigate their space like with the GPS: words of the song become locations of landmarks waterholes, changes in the landscape by elements and disasters. Aboriginal legends lead some Australian scholars to the locations where ancient earthquakes and meteor craters changed the landscape. Some African traditions connect earthquakes with the spirits of some famous leaders that have recently gone to the Underworld. The terrible sound of tremor is the iron gate closing or the spirit’s anger with some recent misbehavior of their people.

One of the most famous oracles in the ancient world, Pythia, resided at the Temple of Apollo at Delphi that was built directly on the fault line – a crack in the Earth’s crust. There were natural springs, and even more importantly, gas fumes from underground reservoirs. Some of these gases, such as methane and ethylene affected the priestesses putting them into a state of euphoria. This, alongside some other natural substances (such as laurel leaves), carried them into a state of trance that enabled communication with gods. In 373 BC the Temple was destroyed – by an earthquake, naturally – but it was rebuilt on the same spot. The ancient Greeks did not have anything against the tectonic activity, on the contrary. It provided them with several really important features: freshwater, hot water for baths, fertile pockets of land, terrain suitable for natural defense.

How did people deal with the damage they caused? Did any country/empire or ruler undertake some actions to help the victims?

The help for the victims of the Messina earthquake of 1908 was quite international. Russian, French, and English battleships and cruisers that joined the relief, as well as sailors of the US Great White Fleet, joined relief efforts. The high extent of the grave situation was evident in the measures imposed by Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti. The martial law dictated that all looters (even if it had been just for food, to survive) were to be shot.

There are differences in the response towards hardening structures after the quakes. Italy has been hit by dozens of quite strong earthquakes in the last fifty years. Still, the majority of the renovated buildings, unfortunately, does not comply with anti-earthquake standards. This can be analyzed from several angles, including the profile and age of Italian traditional architecture. Infrastructure approaches and the cultural heritage protection standards are somewhat different than, for example, in Japan, a country which is proverbially shaken quite often. Furthermore, the anti-seismic regulation in Italy dates from the 1970s, while the same regulation in Japan started in the 1920s.

The Great Hanshin earthquake, known also as the Kobe quake of 1995, saw some quite positive aspects of responding to the second-worst earthquake in Japan in the 20th century. Firstly, there were more than a million volunteers helping the relief efforts in the first 90 days following the disaster. There were more than 120,000 structures that fully or partially collapsed – it took three full years to completely remove the debris. Secondly, a relatively poor response to the catastrophe on the national level was significantly improved; for instance, the government can hold the emergency meeting of its crisis management team in 30 minutes nowadays. Some other urban, political, and social measures were taken, and one can expect a quite better response in the future. Nonetheless, the merciless chthonic strength that in 1995 ashamed Japanese engineers, arguably the world’s finest still poses questions that pend over the heads of the government.

Did laws adapt to the possibility of earthquakes, and when did people start to think about the insurance?

Earthquake insurance is a quite complex issue, so governments and insurance companies deal with it in different ways. The complexity lies in the nature of this disaster – it strikes almost indiscriminately all structures in a particular area. On top of that – which is a problem for both homeowners and insurance companies – the quakes are very often accompanied by other elements, such as fires and floods, largely due to problems with gas or water pipes. Unfortunately for everyone, the earthquake rarely comes alone, but rather with some several nasty companions.

In Turkey, for example, earthquake insurance is compulsory. In Japan, there is an Earthquake Reinsurance scheme (started in 1966 and revised several times) through which the government helps the insurers with billions of US dollars (up to $ 40 billion in a single year). In the US not many people buy earthquake insurance, even fewer in Italy where less than 1% of homeowners are insured for earthquakes. Italy has quite an unpleasant tradition of being uninsured for natural disasters. Attempts to introduce it failed for two main reasons: the costs involved and the difficulties in assessing the risk.

Is there a difference in the cultures that differently approach the explanation of earthquakes?

As I mentioned in our previous interview, there are cultural variations in ways how people experience and express emotions. Nevertheless, some constants have been described across cultures. For example, when it comes to disgust, members of all cultures react to the following: bodily excretions (feces, vomit, blood); something rotten, diseased or dying; filthy places; sexual intercourse with the members of one’s family; heavy injuries. Disgust protects us from pathogens and other harmful influences.

Similarly, fear protects us from dangers. There are so many noted phobias, such as acrophobia (fear of heights) or pyrophobia (fear of fire), but they all could be categorized in just several groups, shared by all cultures. The ultimate fear that can provoke terrible anxieties is of existential nature or simplified: the fear of death, of no longer being. Secondly, there is a fear that something will happen to our body, that we’ll lose a limb, or it will be invaded by a foreign matter/agent; this provokes the fear of snakes, insects, bacteria. The third fear relates to the loss of autonomy: that we’ll get trapped, immobilized, confined (claustrophobia in all forms). The fourth is the fear of loss, abandonment, rejection; while the fifth is the fear of ego-death – i.e. the collapse of our constructed sense of all the elements (often not palpable) that make us the persons we are.

In this sense, it is obvious that there are elements of several fear categories connected to earthquakes (seismophobia). Humans fear for their life, there are serious threats that the falling debris will provoke injuries to their bodies, or trap them beneath the rubble. This might be an explanation of why we all feel a state of shock after a serious earthquake, and why people may display questionable behavior just after the disaster. A cocktail of very unpleasant emotions leaves traumas on everyone.

Do we have earthquakes mentioned in literature or other forms of art?

From the Greco-Roman traditions, I can remember only short but powerful references to all sorts of ‘shakings’ attributed to gods and their activity. The London earthquake of 1580 was so powerful that it found a reference in, among other literary works, Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. The Nurse (Act 1, scene 3) takes it as a milestone, dividing the time before and after: “Tis since the earthquake now eleven years”. Gentleman Arthur Golding, who famously translated Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the work that inspired Shakespeare and so many others, wrote a Discourse upon the earthquake, just one of three of his original writings.

Approximately once every 200 years, a powerful earthquake wreaks havoc on Lisbon, Portugal. After terrible shakes of 1321 and 1531, the 1755 earthquake (one of the most destructive in history) was well documented in visual depictions and documents. This earthquake is also important because of the questionnaire created by the famous Portugal statesman Marquis of Pombal. This document was sent to all parishes of the country, asking information about the direction in which buildings collapsed, the change in the sea level, fires, and some quite intelligent details which were very useful for scholars to reconstruct the nature of the earthquake and the extent of the damage. This was indeed the first attempt to describe an earthquake with a scientific method and the Marquis was considered a proto-seismologist.

There is a quite impressive collection of 19th-century Japanese woodblock prints that allegorically depict earthquakes and the abovementioned giant fish Namazu who causes them. One can clearly contrast those with realistic images of late 18th-century paintings and engravings of the Portugal earthquake. In the collection related to the Great Nobi quake of 1891 one notices some elements of a cross-cultural ‘tension’. Namely, one of the favorite motifs of Japanese artists was the destruction of Western imports, such as railroads, telegraph wires, and brick buildings in earthquakes. Japan opened to the West in 1853 and many of these features of contemporary engineering and technologies were brought to Japan. They were regarded as supreme until nature challenged these achievements of civil engineering.

In more recent history, I read about Christina McPhee and Susan Norrie, artists who created a video and digital representations of quakes associated with memory and emotional response such as fear, traumas, and anxieties. They explored correlations between seismic activity and the human mind, the triggers, and reactivations of traumatic memories. Performance artists can quite interestingly represent and interpret the intertwining of all these phenomena such as the tremendous activity and the power of nature, the fragility of humans, and all the triggered psychological states – the immediate and those lingering for weeks, months, years.

When it starts shaking, there are a lot of these seismic waves that truly play with our bodies and minds, in various ways. The energy unleashed by the most powerful earthquakes is sometimes beyond imagination, it could power whole countries for months. An earthquake was recorded that slightly changed the rotation of our planet. More probable ones, those in the magnitude of 6.0, have the energy of a nuclear bomb. There are earthquake simulators – at the Natural history museum in London, for example – that can give some ideas of how terrifying they can be. Hopefully, that will be as close as you will ever get to experience one of these devastating quakes.

Mirko Sardelic PhD Interview: History of Pandemics: Lessons to Apply to Corona Crisis

March 29, 2020 - A look at the history of pandemics and what we can learn and apply to the current coronavirus pandemic. TCN's Aco Momcilovic interviews Mirko Sardelic PhD.

Interviewer: Aco Momcilovic, psychologist, EMBA, Owner of FutureHR

Interview with Mirko Sardelic, PhD, Research Associate at the Department of Historical Studies HAZU, Honorary Research Fellow of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions (Europe 1100-1800) at The University of Western Australia; formerly a visiting scholar at the universities of Cambridge, Paris (Sorbonne), Columbia, and Harvard.

Intro: The world is facing one of the biggest global crises of our lifetime. Many individuals are feeling that this is an unprecedented event that will have a major impact on their lives and society. And we are definitely on the verge of a new era; the future will be quite challenging. Therefore, this is a good time to reflect and observe this current situation in the historic context. How much do we know about similar situations, and is there something we can learn and apply to this situation? Some of the answers and comments will hopefully be provided by my friend and history expert – Dr Mirko Sardelic.

Q1: In written history, do we have records of similar pandemics? How many of them were on a comparable level to this Coronavirus situation?

Human history is quite rich when it comes to pandemics. The one we are experiencing today – from what has been known so far (though we must be aware that the pandemic has just started) – may arguably appear as a much milder version of what must have been happening during medieval and early modern plague epidemics. The Justinian plague (541-542 AD) killed millions of people in the Mediterranean zone and beyond. The plague of 1340-50s (known as the Black Death) killed more than 100 million people worldwide, reducing the world’s population by one quarter, and cutting the population of Europe in half. For the next several hundred years deadly outbreaks and epidemics of plague-ravaged helpless humanity in every decade. The last recorded plague in Europe was in 1815. In no time, the first recorded major cholera pandemic started in 1817, and by 1823 had killed millions spreading from India to Southeast Asia and towards Turkey and south Russian lands. There were five major pandemics of cholera in the 19th century alone. In short, every generation has experienced or at least heard of terrible deaths by microbiota. (the Croatian language keeps the phrase used for horribly filthy places one should avoid by all means: ‘kuga i kolera’ – meaning plague and cholera: our folk immortalized the two in this superlative of the adjective ‘filthy’.) Nonetheless, the fact that there were so many horrifying epidemics does not mean we should underestimate this one, as it looks quite serious.

Q2: First scientific data indicates that COVID 19 is more lethal than ‘ordinary’ flu, and estimations of the death rate range between 1 and 3.5% usually. While still counting the number of infected in hundreds of thousands, and the number of dead in tens of thousands, it is clear that numbers are going to be high. But again, it seems that they were nowhere close to the devastating epidemics that raged before. What were the deadliest diseases we had in the past?

What the world knows by the name of Spanish flu (that had very little to do with Spain) infected ca 500 million people – which means almost every third inhabitant of Earth was infected – and it took approximately 50 million lives. One might estimate that the death rate was ca 10%, although this number varied, e.g. some native American communities were almost completely wiped out, most probably because they had never been exposed to similar viruses to which Eurasian populations have acquired some resistance. The Bubonic plague’s death rate was approximately 50% and many contemporary sources claim it was more merciless with younger people. One should, however, bear in mind that the diet, hygiene and overall standard of 14th-century people was quite modest and inadequate, by any contemporary criterion. Very recent Ebola outbreaks had mortality rates ranging from 20 – 70%, but have never developed into a pandemic, due to the nature of the virus that can survive for only a short time outside bodily fluids. It seems that there is often a kind of balance between the contagious and deadly aspect of a virus – but it is epidemiologists who should be explaining this.

Q3: Modern science, and the context of the world in the 21st century, will, fortunately, limit the damage of any disease. It seems that it is very hard for us to imagine the context in which people lived before, without modern medicine, scientists and other tools that we use today. Can you picture that for us?

As the Black Death raged, in October 1348 King Philip VI of France required the medical faculty of the University of Paris to provide an explanation of the plague and its origins. Their response in the Paris Consilium was that the plague had been “caused by a conjunction of the planets Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars at precisely 1:00 pm on 20 March 1345.” In words of a contemporary, Belgian astronomer Simon de Couvin (also called de Covino), who first used the term Black Death: “For Saturn is excessively cold and dry, and as a result is a corrupter of human life”. Once the ‘celestial’ cause was determined, the second step followed: getting rid of the bad air. Ancient scholars Galen and Hippocrates had warned of dangers associated with bad air. It could be the product of swamps, piles of corpses, decaying animals and vegetation, human and animal waste, and stagnant air. Medieval towns had laws against anything that stunk, believing that stink kills. The physicians made a good observation: the dreaded disease transferred through “contagious conversation with other people who have been infected”. Also, objects there were ‘infected’ by the sick were also marked as dangerous.

Imagine this: the Black Death creeps into a town, taking away ca 50% of the population. The only prevention available are staying away from bad air, strict isolation, and prayers. No effective cures are available, even more, no hopes of a non-celestial cure. There is some hope that it would eventually go away though, but there is no reasonable expectation that scientific institutes might come up with vaccines or new-generation drugs. There is no real-time news with epidemiologic advice, no electricity, no running water, no trained medical personnel (in the modern sense), no respirators. On the contrary: there are scarce amounts of food (if any), of light, of heating. Deaths – often quite violent – were omnipresent, even without pandemics. People were cut by sabers of invaders and pirates, factions of social and religious strives carried on brutal executions of their adversaries. In the 16th century, German medical student Felix Platter reports that he rode past a place where “pieces of human flesh hung from the olive trees”. People quite often transposed verbal fights into cutting flesh in duels or violent pub brawls. On top of that, the plague had such disgusting symptoms: the bubonic variant had terribly swollen lymph nodes in the neck and armpits, while the septicemic variant saw its patients vomiting, bleeding from the mouth, nose, and rectum; the extremities got black. All that produced more decaying and more bad air – horror for all senses!

Physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, but also many self-proclaimed healers came up with advice and dozens of remedies, with hundreds of ingredients. In major cities, a stuffed crocodile once hung from the ceiling of best apothecaries in Europe: a symbol that they do something extraordinary and that they have the best-imported ingredients. On the other hand, in the country, the rural folk put more trust in their ‘healers,’ ‘root-wives,’ ‘cunning women’. Most of them had an elementary knowledge of natural processes and wide experience, which meant they could help much in certain matters. Authorities tried to forbid the practice of folk healers – some say it was hard to distinguish between the healer and the witch. Nonetheless, most of these women had an important role as midwives, especially in the times of plague.

Q4: Surprisingly but even today we have anti-vaxxer movements, and other groups who believe in ‘weird’ remedies for illness, like vitamin C or garlic. Is it fair to assume that this way of thinking was standard in the past centuries? What did people then believe it would cure them?

One should have respect for ‘folk’ remedies and prophylactics, such as garlic, lemons (ie. the vitamin C-rich foods), honey, brandies, ginger, and a range of others – as accumulated experience shows they are helpful to an extent. My great-grandmother always mentioned chicken broth as a sort of universal healing concoction. The ancestors taught her that – many generations cooked bone broths. Nutritionists’ analyses showed that those broths rich in calcium, magnesium, collagen, and gelatine are indeed beneficial for some processes in our organism. The tradition has preserved what the collective experience considered as good, and this should be respected. Nonetheless, what should also be very much respected is that there were individuals and groups of scientists who dedicated a lot of their time to research the causes of human illnesses, their treatment, and improvements in the standard of human life. The same is with technology: not only can we indicate the presence of a certain virus/bacterium, but also their size, structure, and weaknesses are known.

You have mentioned the anti-vaxxer movement. As a psychologist, you are well aware of what the fear of the unknown can trigger among people. Emotions are often wonderfully helpful. They direct attention to key features of the environment, optimize sensory intake, tune decision making, prepare behavioural responses, facilitate social interactions, and enhance episodic memory. However, emotions can be quite counterproductive as well, especially when they are of the not-adjusted type, intensity, or duration for a given situation. Because of their nature, vaccines – being fluid with an invisible portion of ‘germs’ that we should rather be exposed to in a controlled environment – might produce fear in some. However, we are also aware that many things that are seemingly invasive help us and save human lives on a daily basis: surgical removals of malign tissue or insertions of coronary stents are just some examples. Fear of death is another tremendously powerful drive: it paralyses reasoning and makes people take otherwise unthinkable actions.

Fear is a mechanism of alerting oneself that the danger is present and that protective measures need to be taken. Fears come in all shapes, sizes (intensities), and durations. Plague (with a good reason) triggered the fear of death, the one that is horrific and that lingers. What were medieval people prepared to do to cure the plague? As one can imagine: everything, literally. One of the most prescribed drugs for preventing and curing the plague was called theriac, the monopoly of which was in hands of Venetian apothecaries. Many variants were known, but it usually took some 60 ingredients and 40 days to process. The key component was roasted viper flesh. ‘Common’ ingredients included honey, the meat of wild beasts, and dried scorpions. Nonetheless, some special ingredients could include nothing less but a ground mummy. And, like good whiskey or rum, the best theriac had to age 12 years. A literary image finds buboes as representations of death literally attached to life. Those would burst on their own in the second week of infection, or the surgeons would drain them.

Surgeons also let blood from their patients, either by incisions on their veins or using leeches which were unpleasant but painless. On their own, the patients tried aromatherapy, eating gems crushed in powder, smeared themselves in in numerous creams, balsams (some of which contained even feces), vinegars, onions, animal parts – no need to elaborate, just use your imagination. One remedy for bubonic plague was quite popular at least from the times of the legendary Islamic physician and philosopher Ibn Sina (in Europe known as Avicenna) from the early 11th century. Live chicken, with some feathers plucked, was held against buboes. It was believed that in this way the chicken would pull the poisons from the buboes into itself. If a chicken died in the process, it had to be replaced with another, which was repeated until one survived the procedure. This ‘live chicken treatment’ was practices for several hundred years, well into the 17th century.

In medieval and early modern Europe doctors knew that there was not a definite cure for the plague, and therefore many of them did not even want to get near the infected. There were priests who refused to give absolution to dying plague victims. This led to the appearance of the plague doctors, hired by cities, and covered in raven-like masks with long beaks. The masks ‘protected’ not only from bad air – which was the heart of disease – but also from the deadly gaze of the dying, which was also feared. For that purpose, there were herbs, spices or vinegar in the beak. These doctors cared for the sick, coordinated the removal of corpses, and registered deaths. One of the most notable was Michel de Nostredame, later called by the Latin variant of the name, Nostradamus – who lost his first wife and both their children to the plague of 1534. Apart from these who could not do much, miracles were expected from St Rocco and St Sebastian, patron saints against the plague.

Q5: After every major event of this kind, there were smaller or bigger shifts in the societies. Usually, it got better in some way. What were the changes after the biggest historical epidemics? What were the economic and political consequences?

Societies learn – or, I would rather say – experience things for themselves. Everyone learns better from one’s own experience. During this pandemic, we will remind ourselves what it means to take prophylactic measures (prevention), how efficient quarantines are, and how (un)disciplined people can be in the times when extreme measures are needed. People are often reckless, which can prove costly. Also, coping with the fear of the unknown can lead to either paralysing effects or, on the other hand, ignoring the threats. This is the moment where experts need to guide and create balance.

Late medieval plagues led to improvements in the way medicine is practised and perceived. ‘Remedies’ provided by alchemists proved to be inefficient, even dangerous and lethal. Mediterranean coastal cities started using lazarettos – specialized complexes of buildings where the quarantine was performed. (The word quarantine came from the Venetian word for the number forty, as that was the number of days after which it was considered safe to bring out goods or people without fear of some latent incubations). The first quarantine was established by the maritime Republic of Dubrovnik (Ragusa) in 1377, as a result of a need for safer continuation of trade.

The 19th-century epidemics caused big leaps in medical science. One of the fathers of epidemiology, English physician John Snow, traced the source of a cholera outbreak in 1854 in London. Cases of chicken cholera and anthrax led Louis Pasteur, French biologist, to promote several life-saving practices in disease prevention. He created the first vaccines for rabies and anthrax, and is credited for many other important discoveries. What was known as the third plague pandemic (that began in Yunnan, China in 1855, and was active till after WWII), that killed dozens of millions of people in China and India alone, attracted bacteriologists who sought after the causes of the disease. In 1894 Swiss-born French Alexandre Yersin and Japanese Shibasaburo Kitasato isolated the bacterium (named after the former, Yersinia pestis). The cause of plague finally got identified.

Therefore, I would say the medical and technological discoveries have made a huge difference. It took humanity thousands of years to learn how to prevent and treat plague; then, starting from the 19th century, it took a century, then decades to make some breakthroughs. The HIV virus took many millions of lives, but it took decades to be put under control. In the 21st century, one may count that vaccines and successful treatments for new diseases will be available within several years, possibly even less, which is a tremendous improvement. One can see the progress in real-time!

As far as the economic consequences are concerned, I am sure that the likes of Joseph Stiglitz experience difficulties when it comes to global prognosis. From a historian’s point of view – in the long-term, humankind recovers, in all its activities – no doubts about that. When it comes to Croatia in the short-term, things could be worrying though. Many things look quite gloomy now: businesses struggle already, and we are not even in the peak of the pandemic; 20% of the GDP is tourism-based; one of the crucial trade partners, Italy, is on her knees, and so on. These challenges will need to be addressed by economists and politicians in the coming months and years. Both short-term and long-term strategies are much needed.

Q6: What was the response of people and rulers/governments during epidemics? What do you think we could use from past experience and implement in today’s way of thinking?

It is important to avoid the negative sides, i.e. abuses in channelling fear. For example, during the Black Death in some Northern European countries, people noticed that Jewish communities (due to their good hygiene practices) had fewer deaths than others. This led to antisemitic movements in some countries; many Jews were persecuted, even massacred, in spite of the efforts of Pope Clement VI who tried to protect the Jews against allegations that they had their hands in the plague outbreak. In our times many Chinese must have experienced quite unpleasant situations. As far as rulers and governments are concerned, history does record protective measures concerning the economy, public health and safety. On the other hand, again, there have always been (more or less successful) attempts of rulers to seize more power – as extreme situations require extreme measures. We should all be aware of what happens to our civic freedoms during, and especially after, the pandemics. Even more importantly, we all need to do our best to keep the fear down. History has shown that unleashed fear can sometimes be as dangerous as the initial danger itself.

In my opinion, one thing is for sure: there are no limits. The dimension of viruses is measured in nanometres (10-9), while the distance from Earth to Sun, for example, is measured in gigametres (109). There are so many worlds in-between these 18 powers of scale, and this is not even half of the spectrum. The same is with history – history has seen pretty much everything: millions of years, the evolution of animals and societies; projects that fell victim to greed, fear or egoism; achievements that were built on hope, bravery, enthusiasm, joint efforts. History can teach a lot, but often, for various reasons, it does not put its lessons into full effect. Maybe this is because it’s huge and inert, while our brains prefer swift stimuli, quick(er) solutions, and palpable outcomes. Nonetheless, one important lesson is that nothing is impossible, and that things can go in uncountable directions. They have led us this far, to this scenario, out of gazillion possible ones, (among other factors) thanks to people who invested their time, resources, and lives into making our existence enjoyable, interesting, and way safer than they have ever been.

An ordinary human couple experiences everyday struggles in decision-making, let alone those of societies. Generally, most of them want to be healthy, enjoy personal freedom and experience economic prosperity. We have seen that humans can achieve pretty much anything they want. There are just two questions (to start with): At which rate? And at what cost? There were some ethical dilemmas behind the curtain: should one ‘sacrifice’ the lives of the old and immunocompromised (who are the most likely victims of the present pandemic) in order to recover the economy more quickly? The pros were suggesting that the damaged economy would lead in numerous job cuts, which again leads to poverty, depression, ‘killing-us-slowly’ scenarios. On the other hand, what can be more human than taking care of the most vulnerable members of our society: the young, the elderly, the sick, the fragile? These are the times when solidarity, unselfishness, and caring come in.

Finally, can it be done respecting the equilibrium of our eco-system? Let us not forget: humans are unique eco-systems as well: our viruses, bacteria, and fungi live in our cells, in our gut, on our skin. Their number is measured in trillions (a million millions). We might have affected them significantly, but it is still hard to say what would be the long-term result of tampering with what has undergone millions of adaptations, millions of mutations. Exposure to some viruses resulted in some of the most fascinating animal and human mutations, and evolutions. The story of humans and viruses continues: we have gone through so much together.

For the latest on coronavirus in Croatia, visit the dedicated TCN section.