RBA: Croatian Clients' Money And Assets Safe

ZAGREB, 3 March 2022 - Raiffeisenbank Austria (RBA) on Thursday underscored that the bank is not directly exposed nor is its business directed at the Russian or Ukraine markets, adding that its clients' money and assets in Croatia are safe.

Regarding Raiffeisen Bank International (RBI) and its exposure to the Russian and Ukraine markets and its connection with the local RBA bank in Croatia, "all RBA bank services, products, all domestic and foreign payments, with the exception of those covered by sanctions, are accessible to clients."

RBA Croatia is one of 13 banks within the Austrian Raiffeisen Bank International Group (RBI) operating in central and eastern Europe, RBI said and added that based on experience over the past years, it has developed a proven approach to protect its clients.

The approach consists of conservative management of business activities, preventing the exposure of clients to any significant risk on the Croatian market. It includes a high level of liquidity and capital, which is significantly above that required by European regulators, and a very strict strategy resulting in self-sustainability.

RBA management board president Liana Keserić said that while it is witnessing the destructive consequences of the current conflict for Ukraine's residents, the bank is doing everything to offer its clients what responsible bankers are required to provide - a secure bank and secure access to money, products, and services.

For more, check out our business section.

Mirko Sardelic PhD: The History of Money

July 13, 2020 - We live in the times of the fastest changes ever. The financial sector, although rigid and regulated itself, is also facing different changes. With rumours of upcoming recession even before the COVID-19 crisis, and especially with the number of concerns that we are facing at the moment, it seems a good time to immerse ourselves in the pool of historical review. Hopefully, this will give us a better perspective of our current situation, and maybe we will learn something useful for the future.

Interviewer: Aco Momcilović, psychologist, EMBA, Owner of FutureHR

Interview with Mirko Sardelić, Ph.D., Research Associate at the Department of Historical Studies HAZU, Honorary Research Fellow of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions (Europe 1100-1800) at The University of Western Australia; formerly a visiting scholar at the universities of Cambridge, Paris (Sorbonne), Columbia, and Harvard.

How did ancient societies exchange goods and services?

I would say that you have just used the keyword: exchange. When people meet, they exchange greetings, hugs, gifts – or, if it is not so friendly an encounter, they exchange fears, stereotypes, loathing, disgust. The history of exchange is inconceivably long and diverse. But no matter how friendly or hostile relations were, humans started to exchange goods and services a long time ago.

Everything started with barter: I give you my surplus of the fish I caught in exchange for the furs of the animals you hunted. This functioned for quite some time, although it was often problematic to negotiate ‘the exchange rate’ every time one wanted to exchange their fox fur for the other person’s grain, pearls, amber, tools, or weapons. With a limited number of items exchanged, this could be arranged without major difficulty, but once the number of objects and commodities rose, some new mechanisms needed to be established. This led to the creation of first currencies.

When were the first currencies created? Who created them? What were they made of?

First, people used standardised useful objects as currency, all most likely made from metal: it could have been an axe, a knife, a cauldron, or a ring. (Ancient non-metal objects very rarely survived intact to be discovered by modern-era archaeologists anyway). When discussing objects of ancient cultures, archaeologists and anthropologists often struggle to discern or analyse their (multiple) usages. This is because the same object could have religious, financial, and ornamental use at the same time.

Currencies that were not metal were mostly natural. In China, Africa, and the Roman Empire, salt had, by contemporary standards, unimaginable value. Maritime states used this, but continental states also gained amazing wealth from this precious product we all need daily. Take, for example, the oldest-known salt mine in history: the Halstatt salt mine (Austria); or one of the most famous medieval mines, Wieliczka, upon which the splendid city of Krakow (Poland) built its riches.

Animal skins were used widely: beaver or squirrel pelts, marten, bear, or buck. The names of some of these animals can still refer to money in some languages: in English people still use the term ‘bucks’, while Croatian currency is still kuna (marten). Aztec and Mayan cultures used cocoa beans for currency. They kept them in bags containing 8,000 or 24,000 beans. One bean could be exchanged for an avocado, while 100 beans could be exchanged for a turkey, or a slave, depending on the time period and the particular area of Central/South America.

In Babylonia, metals (such as silver and copper), and barley grains were both used as currency. The value of one shekel was 180 barley grains. Hammurabi’s Code, more than 4000 years old and one of the most fascinating legal codes in the history of humankind, regulated the payment of field workers in grain, while surgeons, brick-makers, and artisans were paid in silver currency. Seeds of carob (Greek keratos, or Italian carato) were used to relate to the fineness of gold – even today we use the same word, carats (as in 24-carat gold) for the same purpose. Amber, ivory, jade, rice, eggs, sheep, goats, camels, seashells, coconuts, and many other natural products were used as currencies.

How was the exchange between different currencies undertaken? What were the first exchanges?

Throughout history, humans often set, in customary law or in legal documents, items that could be exchanged for something else and in what circumstances. Many societies even had a fixed price for human life: if a person killed someone, they could (or were obliged to) pay the sum to make up for this offence. In early Germanic societies, it was called weregild: blood money. It was prescribed how much human life was worth, depending on the deceased person’s social status. There was even an amount for killing the king, which suggests that it had happened. Even the root of the word ‘pay’ comes from Latin pacare – to pacify or make peace with the creditor or the one you offended by killing their kin.

As we can see, Western civilisation owes so much, in terms of etymologies and financial traditions, to the Greco-Roman world, as well as to late-medieval Italian merchant states. Words such as ‘money’, ‘mint’, and ‘monetary’ have the same root. They all come from ‘Moneta’, the nickname for the Roman goddess Juno. Traditional etymology tracked its root from the verb monere – ‘to warn’. It is likely that the etymology of the word ‘cash’ is again Latin (from capsa – ‘(money) box’; Italian cassa), although some derive it from Tamil word casu – ‘copper coin’, via Portuguese caixa. Salary comes from Latin word salarium, which was a Roman soldier’s allowance to buy salt (sal in Latin).

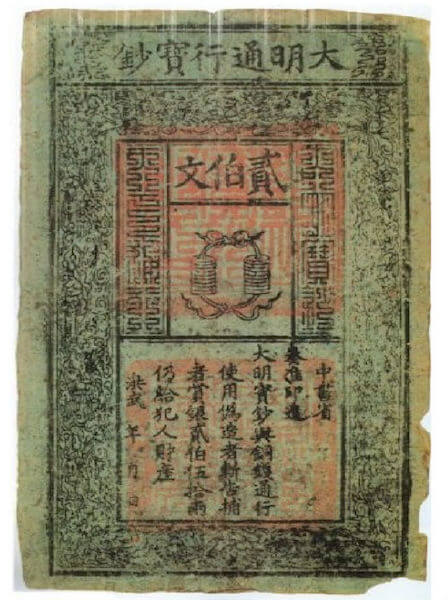

Italian city-states, such as Venice, Genoa, and Florence, had trade networks and outposts throughout the Mediterranean world and the Near East and developed quite sophisticated financial tools and means of exchange. The same can be said of Arab merchants of the period. When studying monetary history, one should also look into the financial traditions of China, where first paper money was put into circulation, more than a thousand years ago. Among these nations, a lot could be learned about the exchange between currencies. However, the first exchange offices as we know them in the Western world today were probably established by the Dutch and the British, who became global (financial) powers in the 17th and 18th centuries.

FIAT money is an invention of the late 20th century? What was the monetary base in the past?

Not everyone will know what ‘fiat money’ is. This is money not linked to physical reserves (of precious metal, for example), but its value is arbitrarily defined by governments or rulers. In short: gold coins can be worth exactly their weight, while a full bag of paper notes is worth as much as the authority that has issued the currency agrees on its value. The other type of money is the mentioned ‘commodity money’, whose value is intrinsic, i.e., its value comes from the value of the commodity from which it is made, such as silver or gold. The last type is ‘representative money’, which is usually a piece of paper representing the worth of the sum, or the intent to pay.

For three thousand years, the monetary base has consisted of reserves in (precious) metals: in ancient China the standard was copper; in Assyria lead; while in later centuries the standard has become silver and eventually gold. Gold could never have been a sole monetary reserve, as there would never be enough of it. It is a fabulous metal that is literally out of this world. It cannot be produced on Earth, although alchemists put so much effort into attempting its production during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. All gold deposits on Earth that have been blended into our planet’s core and crust were created by explosions of distant stars. One should bear in mind how rare and heavy gold is. The total amount of gold that has ever been mined or discovered on Earth throughout history is estimated to be between 200 and 400 thousand tons, which equates to the volume of four to eight Olympic swimming pools. This is because the specific mass of gold is 18.6 kg/litre. Just for comparison, a regular airline cabin bag (standardised at 50x40x25 cm) has a volume of 50 litres. If you packed it perfectly with gold bars, you would end up ‘carrying’ a staggering amount of 930 kg of gold!

Today, we have a new revolution with cryptocurrencies. How did money revolutionise societies before?

Money cannot buy everything, but it certainly provides the owner with a high dose of security and freedom. The most important characteristics of modern money are its durability, portability, divisibility, uniformity, limited supply, and acceptability. Metal coins, especially the ones issued by strong and rich monarchs, had all of these. They first appeared some 2,600 years ago.

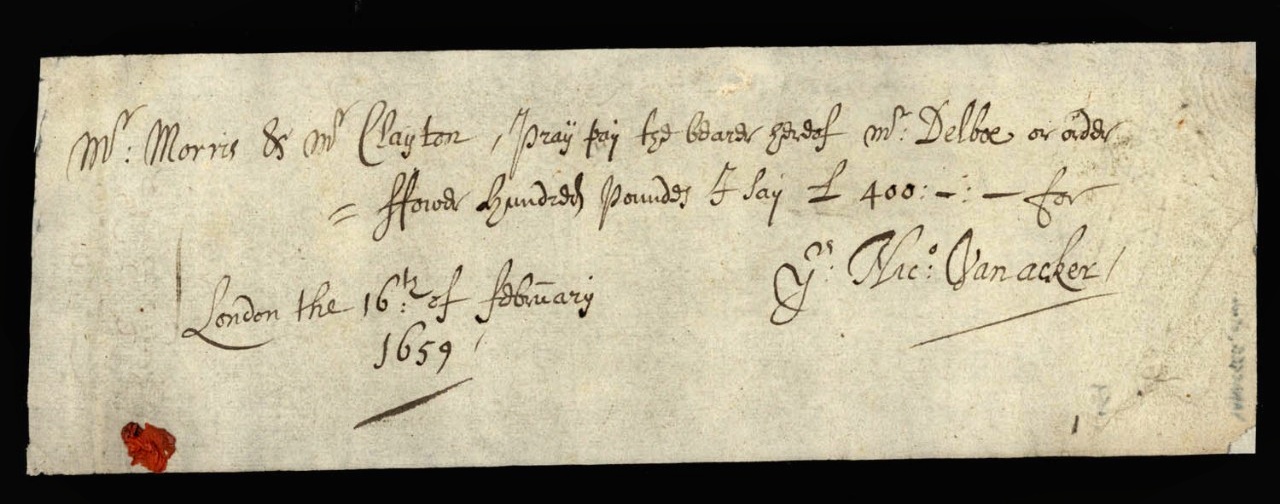

The introduction of cheques was quite an interesting and useful change in the money market. In the Western world, the history of cheques can be traced to the very successful Republic of Venice, ruled by a merchant capitalist elite. In the 13th century, the Republic issued cheques that were used in international trade – replacing huge amounts of silver – which was much more practical, not to mention safe, to transport by ship. Nonetheless, this was not an entirely new invention. Some forms of cheques were used in Mesopotamia, only to be improved upon by Muslim merchants in the Middle Ages. Merchants could exchange silver coins for a piece of paper in Baghdad, one of the most prosperous cities in the world (before it was conquered by the Mongols in 1259), and cash that piece of paper (cheque) in Cordoba (Spain), more than 5,000 km away.

The ‘step zero’ of globalisation is also related to financial issues. What we mean by globalisation today is that I can prepare myself a delicious breakfast from Australian avocadoes, Colombian bananas, Spanish lemons, Irish butter, and Italian prosciutto – but access to such a wide range of products in our households has been mostly a 20th-century standard. What I mean by ‘step zero’ is the moment when the world became connected for the first time. (Of course, in history, one always needs to be careful with ‘first times’, but I use it here just for the sake of journalism, as there is no place to elaborate contested theories). In the 15th and 16th centuries China had paper money and experienced a monetary crisis mostly due to a shortage of silver. Japan was the biggest exporter of silver before Spain took control of huge silver deposits in the Americas. China needed silver and Spain was a major provider, across the Atlantic. However, in 1571 Manila was founded in the Philippines and overnight became a major transit port. The silk and commodities from China were transported east towards America, while the silver cargo went the other way, over the Pacific Ocean. This ‘silver ring’ connected the Americas with Europe and Asia and the world became more and more financially entangled.

Introducing new ideas or technologies into monetary policies is a matter, as ever, of compromise, and it is often a result of embodied interest. There are always advantages and downsides: do we prefer practicality over security issues; or do we favour transparency over the privacy of citizens. Security and privacy issues often change the tune.

We are facing risks of inflation. Today, some countries have enormous inflation. Did it happen before? What were the biggest ones?

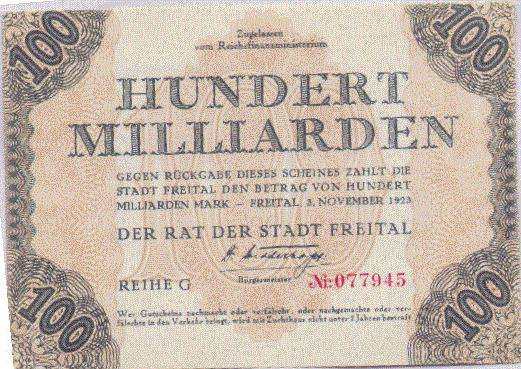

Arguably the most shocking inflations happened in the 20th century. The World wars contributed to those significantly: we can mention Greece and Hungary as examples in the immediate post-WWII period. Nonetheless, Germany’s inflation of 1923 was also terrible – prices doubled every three to four days. WWI reparations were merciless to the German monetary situation. Yugoslavia’s inflation in the early 1990s was also epic. Mementos of these hyperinflations – apart from the terrible trauma of the population who lived through them – still remain in the banknotes of the period: sometimes it can be very hard to count all of the zeroes, e.g., a ten-billion notes were common at the time.

In the Roman Empire inflation could be measured through the quantity of (precious) metals in the coins issued by imperial mints. The coins in a strong economy contained a decent amount of gold. This was slowly replaced by a higher percentage of silver, then copper. In ancient times therefore if one wanted to pump more money into the market (or, more often, into financing troops), one could either issue coins of smaller diameter or reduce the percentage of more precious metals in the coins.

One of the most famous monetary reformers of the Roman Empire, Emperor Diocletian, tried to restrain galloping inflation by fixing standardised gold and silver coins, introducing bronze coins of smaller value, and issuing the Edict of Maximum Prices. This important document regulated maximum prices for some 1,000 articles across the Empire. The most valuable commodities of the time, according to the document, were one pound of purple-dyed silk and a lion – both items valued up to 150,000 denarii. It was an admirable effort, but these measures were both helpful and detrimental. Nobody has managed to save an empire alone anyway.

Could a country become bankrupt in recent centuries?

Humanity has spent a lot of time in the war. Wars bring so much devastation that our first thoughts are most often related to arms, casualties, displacements, refugees, hunger, and suffering. Nonetheless, those who want to win wars first think of how to finance them and how to deliver provisions. Financing wars is always a tremendous effort. It was a huge challenge for rulers who often owed a lot of money to rich individuals. They usually found a way to pay them back through other means: giving them land; trading privileges; monopoly over certain commodities; etc. Many rulers lost their thrones (even heads) because their debt was unbearable or other contenders to the throne had more financial means at their disposal.

In peacetime and modern times countries go bankrupt as well for various reasons, but it rarely happens as modern times developed mechanisms to give loans to those in financial trouble. Long before money appeared, there was debt. Debt is all around us: citizens of all countries have personal and business loans in banks. Almost all countries in the world have loans; the US national debt reached USD24 trillion (24,000,000,000,000) in April 2020. This is more than the debt of the so-called Third World countries combined. It is a debt towards banks, domestic and foreign investors, and others. One can buy and trade with fractions of national debts. However, the connections between indebted governments, their liabilities, and creditors can be rather complex – it is a good topic for another interview by a more competent analyst.

Who were the richest people and how much was their worth?

The richest people are those who feel they have enough. You may say this is a philosophical answer and a pretty dull one, and I cannot agree more. Then again, many essential human achievements require so much of ‘dull’ work. No wonder there are many cartoons and movies that imagine a pill that can skip some thousands of hours of dull training and make (some of) us experts within minutes. There is so much hard work behind pretty much any useful physical or intellectual activity. (Apologies for this red herring, I am often keen to remind my students of Hercules at the crossroads).

Back to the richest people in history: pharaohs, emperors, kings, entrepreneurs, bankers – so many who were both incredibly wealthy and influential. In the Mediterranean world, for many centuries there was a saying ‘wealthy as Croesus’. This unimaginably wealthy Lydian king (6th century BC) arguably was the first ruler to have issued gold coins with standardised purity. Croesus was defeated by another extremely powerful and rich king, Cyrus the Great, who established the Persian Empire, the largest in the world at the time, stretching from the Indus river to the Mediterranean.

In the Roman world, I could single out two figures: Emperor Augustus, and General Marcus L. Crassus who financed Caesar’s ascent, and died when Augustus was a young boy. Crassus was notoriously rich, and he accumulated his riches “by fire and war” (as Plutarch, one of the finest historians, so nicely put it). He was a military commander and entrepreneur who traded in real estate, among other things. He even had his own fire brigade that extinguished fires in Rome depending on Crassus’ interest, i.e. whether or not he planned to buy that estate.

In the common (AD) era, one can mention Emperor Shenzong of the Song Dinasty (11th century); Genghis-khan, the ruler of the largest empire in history (13th century); Mansa Musa I, the King of Mali (14th century) who controlled a considerable cut of the world gold reserves of the period; or Emperor Nicholas II of Russia, whose personal wealth in 1916 is estimated up to 300 billion of today’s US dollars.

Jakob Fugger (1459-1525), merchant, banker, and mining entrepreneur was arguably one of the richest people in history. Some estimates suggest his net worth was several hundred billion in today’s US dollars. This is more than twice as much as today’s wealthiest person, Jeff Bezos, whose wealth has been estimated between USD100 and 200 billion. Of course, this is subject to change, and as early as next year we might be talking about different ratios or the new richest person on the planet.

Three contemporaries John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and Henry Ford, made their fabulous fortunes on oil, steel, and cars, respectively. Their fortunes were more than USD100 billion, each. Carnegie gave an amount equivalent to one billion of today’s US dollars just for building public libraries in the United States of America. Rockefeller made huge donations to the church, and for educational and health purposes. At the turn of the 21st century, Bill Gates was for the wealthiest person in the world. He also donated huge amounts to social, educational, and health projects. He has been interested particularly in eradicating poliomyelitis, a disease that weakens muscles, and many have been saved from diseases as a direct consequence of his donations to research on viruses and vaccines.

Enormous amounts of money very often give birth to greed. Financial reports suggest that eight of the wealthiest people today have accumulated the same amount of money as the poorest half of humanity (which is almost four billion people). Two billion people live on several US dollars a day, and reports estimate that, due to the COVID-19 crisis, another half a billion will be pushed into poverty. These differences, which have deepened over the last couple of decades, could be a big challenge to the global society.