Croatia Police Incident Not as The Guardian Reported - Nigerian Ministry

Abike Dabiri-Erewa, Chairman/CEO of the Nigerian Diaspora Commission for the government of Nigeria, responded to the allegations of two Nigerian students who came to Croatia to play table tennis and mysteriously ended up in Bosnia, after The Guardian article appeared on a local Nigerian portal.

Nigerian Minister of Foreign Affairs Intervened

“The Minister of Foreign Affairs is on this matter. It’s not as straightforward as you have reported, but the Mimster (sic) has personally intervened. We should give an update as the intervention continues,” she revealed in a tweet on Saturday, December 7.

The Guardian article titled “Police in Croatia deport Nigerian table tennis players to Bosnia” appeared on December 5. Since then the story has been picked up by DW, The Telegraph and others. And, then it appeared in TheCable, a Nigerian portal.

Croatian Police 'Kidnapped' Nigerians According to Žurnal

Žurnal, a portal based in Bosnia, broke this story on December 3 with the headline: “Croatian Police Kidnapped Nigerian Students and Took Them into Bosnia”. The Žurnal article also included a video interview with the students, Kenneth Chinedu Eboh and Uchenna Alexandro Abia, who alleged that Croatian Police apprehended them on a tram in downtown Zagreb. According to the students’ account they were brought to the police station on the evening of November 17, put into a van with other illegal migrants and forced at gunpoint by the Croatian police to cross the Bosnian border.

Žurnal Story Gets Picked Up by The Guardian

Writing from Tuzla, Bosnia - Lorenzo Tondo, a correspondent for The Guardian based in Palermo, Italy - referenced the students’ Žurnal interview in his December 5 article for the publication. He also interviewed Alberto Tanghetti, organizer for the Fifth World InterUniversities Championships in Pula, where the students had showed up without rackets and sports equipment, and competed in table tennis. Mr. Tanghetti confirmed that the young men had attended the competition and that he had identified them for volunteers at the camp in Velika Kladuša, where the men ended up.

However, Mr. Tondo’s December 5 article didn’t include the statement from the Croatian police which had appeared in Croatian media mid-day on December 4. Among other things, their statement disputed the students’ reported Zagreb travel dates and noted that another student in the group of five, had tried twice to cross the border to Slovenia and eventually applied for asylum in Croatia.

First Guardian Article Missing Police Statement

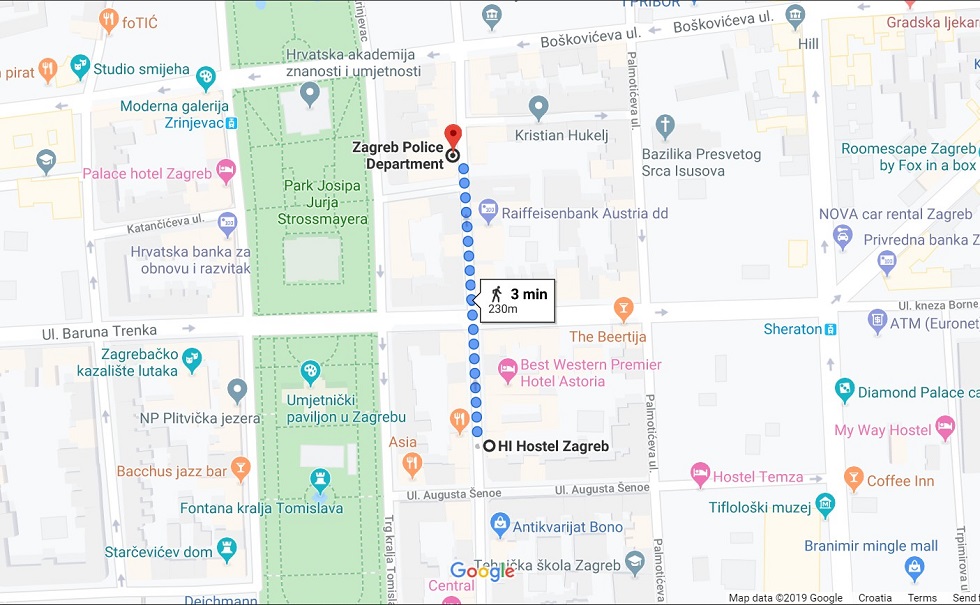

I contacted Mr. Tondo on the evening of December 5 to ask why he hadn’t included the police statement, which had appeared the day before and contradicted key details in the students’ allegations. I also pointed out that several Croatian media outlets had just interviewed the manager of HI Youth Hostel (also on December 5), where the students stayed. I added that the HI Youth Hostel is only 230m from the central police station on the same street, which calls into question why the police wouldn't have accompanied the students back to their hostel to verify their passports. According to the students’ allegations; the Croatian police brought them to the nearby police station instead.

Branimir Markač, the hostel manager, also disputed the students’ claimed check-in and check-out dates. The students stated that they checked in to the hostel on November 17, went for a walk in the city and were apprehended by police, who refused to allow the students to prove their identities and legal visas in Croatia, and took them in a van to Bosnia instead. The manager confirmed the Croatian police account that the students had checked in on November 16, rather than November 17, and checked out with their passports and belongings on November 18.

Mr. Markač also disputed the students’ account that an unidentified “friend” came to his hostel (the name of which the students couldn’t remember), retrieved their passports, and sent them to Bosnia, where local sources confirmed their arrival on November 25. The manager confirmed that no one came to his hostel in search of the Nigerians’ passports. He also emphasized that he would not have handed them over to a stranger.

Second Guardian Article Missing Hostel Managers’ Account

Mr. Tondo maintains that he didn’t obtain a police statement until 6 hours after his first article was published. In fact, he would have had that information the day before if he had been following Croatian media. He also didn’t include the hostel managers' account in his second article, written in Split, and titled “Croatia and Bosnia play political ping-pong over table tennis players”. That article, which appeared in The Guardian on December 6, quotes the Croatian police statement and refers the other Nigerian who attempted to cross the Slovenian border. However, it makes no reference to the hostel manager, even though I had provided him with this information and sources on the evening of December 5.

My correspondence with Mr. Tondo continued December 6, when I asked him the following:

- Did you read articles from any of the Croatian media outlets beforehand?

- Do you follow Croatian media?

- Do you read/speak Croatian/Serbian/Bosnian?

- Do you have an understanding of politics in Croatia?

- Did you contact anyone in Zagreb (besides the Croatian police) where this alleged incident happened?

Mr. Tondo declined to reply and responded that he was going to send my email to his lawyer. To my request for his editor’s name and contact information, he responded that he had already forwarded my emails to his editor and I could seek out that information by myself.

Does Lorenzo Tondo Know Croatian?

Upon contacting The Guardian by phone on December 6, I obtained the contact information for Tracy McVeigh, Editor of The Guardian’s Global Development Desk. I included my correspondence with Mr. Tondo and asked if The Guardian has a dedicated correspondent in Croatia who can follow news in Croatian/Serbian/Bosnian. I also indicated that Mr. Tondo would have a difficult time following the news developments in Croatia if he can’t read or speak the language. And, surely, there is a considerable pool of capable journalists living in Zagreb.

The Guardian Cannot Afford Croatia-based Correspondent

Ms. McVeigh declined to confirm whether Mr. Tondo knows Croatian/Serbian/Bosnian, and indicated that The Guardian, an international publication with over 8 million Facebook followers, cannot afford to keep a permanent correspondent in Croatia. Instead, she assured me that The Guardian has highly-skilled and experienced correspondents who travel to many different countries to write for their “British audience”.

According to the Croatian portal MojaPlaća (My Salary), the average monthly full-time salary for a journalist in Croatia, after taxes, is 4792 HRK (541 GBP, 644 EUR). So, it appears that The Guardian chose instead to assign this story to Mr. Tondo, a correspondent based in Palermo, Italy - who has not indicated whether he knows the local language. And he also appears to have accepted the Nigerian students’ story, reported by Žurnal, as fact.

No Witnesses to Students’ Alleged Zagreb ‘Kidnapping’

Other than contacting the Croatian police for a statement, which was already available to the public on December 4, there’s no evidence that Mr. Tondo made any other attempts to confirm the details of the students’ story. He apparently did not contact the manager of HI Youth Hostel, nor is there any evidence that he was following Croatian media as this story developed. There’s also no evidence that he made any attempts to reach out to the other Nigerian student in the group, who applied for asylum status in Croatia, and is currently being housed at the center for asylum seekers in Zagreb.

“I always knew there’d be a back story to this!” read one response to Abike Dabiri-Erewa’s tweet on Saturday.

“There is. But whatever the circumstances, the most important thing is to get them back,” the senior Nigerian government official replied.

Follow our Politics page for updates on this developing story and the migrant crisis in Croatia.

Croatia Police Allegations: Zagreb Hostel Disputes Nigerian Students' Story

Did the Croatia police (MUP) really abduct two Nigerian students who were legally at a sports competition in Croatia, on a tram just steps away from their hostel in the middle of Zagreb, and banish them to Bosnia?

Kenneth Chinedu Eboh and Uchenna Alexandro Abia, two Nigerian students who came to Pula to compete in table tennis, claim that that is exactly what happened, while MUP claims in a statement that they had checked out of their hostel, the name of which has now been revealed. They allegedly departed the HI Youth Hostel in Zagreb with their passports on November 18 and arrived in Bosnia illegally. However, MUP claims that they still do not know how the students got to Bosnia.

Over the past two days, this alleged expulsion has captured the media attention of Croatia and neighboring states. And, the story has now reached the rest of Europe after it was published in The Guardian yesterday.

Croatia Police and Nigerian Students Not Telling Whole Story

Based upon what is known so far, neither MUP nor the Nigerian students are telling the whole story, according to Gordan Duhaček/Index on December 5, 2019.

It has been confirmed that Nigerian students have obtained a visa for Croatia at the embassy in Pretoria and that they entered the country legally. They stayed at the Veli Joze Hotel in Pula while competing in table tennis at the 5th World InterUniversities Championships. However, their version of events regarding their alleged detention and forcible expulsion from Zagreb to Bosnia have not yet been corroborated.

The Nigerian students ended up in a migrant camp in Velika Kladuša in Bosnia, but were they really expelled by the Croatian police under the threat of violence? That cannot be confirmed, because the claim is based solely on the testimony of two students and has not been substantiated with evidence. And did the Croatian police really abduct them on a Zagreb tram, in front of other riders, in the middle of the city? That allegation has not been confirmed either, but MUP could easily inspect surveillance cameras on Zagreb trams and inform the public of their findings.

Nigerian Students' Story Conflicts with MUP and Hostel Account

The most suspicious part of Eboh and Abijah’s story is that they do not remember the name of their hostel in Zagreb. Then, as they claim, a friend from Croatia sent them their passports, which he collected at the hostel reception desk. Those passports arrived by mail in Velika Kladuša on November 25, which has been confirmed by independent sources from the field. How did that friend know which hostel to go to if they couldn’t tell him the name? Did he stay with them in the same hostel? And what is the name of the friend who sent them their passports?

According to Vecernji List and other sources, the students stayed at the HI Youth Hostel on Petrinjska Ulica 77. That hostel is a mere 230m, or a 3-minute walk, from the MUP central office on the same street at Petrinjska Ulica 30, which casts doubt on the students' claim that the Croatian police wouldn't be bothered with confirming their travel documents at the HI Youth Hostel. According to their allegations, they were taken instead to the MUP central station 230m away.

Students Took Their Passports and Luggage Upon Check-out

Hostel manager Branimir Markač confirmed in an interview with Dnevnik Nove TV that the students spent two nights at his hostel in Downtown Zagreb, checking in on November 16 (rather than November 17 as the students claim) and noted that they spent some of their time in the hostel lobby. They asked the front desk for some information; like the location of the nearest exchange office. After spending their first night and day at the hostel and taking side trips around town; the two Nigerians decided to extend their stay another night, which they did at 22:23h on November 17. Markač says he has their bill as evidence. They checked out of the hostel on November 18 at 11:00h and didn’t leave anything behind. This conflicts with the students’ claim that they were abducted by Croatian police on the evening of November 17, and sent to Bosnia, with their travel documents and luggage remaining at the hostel.

"Absolutely no one came to the hostel for their travel documents, nor would we ever hand over anybody else's belongings," Markač emphasized.

MUP has also claimed that Eboh and Abia left the hostel for an unknown destination, after checking out, taking their passports and paying their bills.

Who sent their passports to Velika Kladuša?

Is the friend who sent the Nigerian students their passports by mail (allegedly after retrieving them from the HI Youth hostel) their colleague from Nigeria? He also stayed in Croatia after his six-day visa expired and requested asylum with his passport at the MUP central station (230m from the hostel) on November 27, after reporting his passport lost at the same station on November 18. The police know his name but have not yet published it. He is likely being housed Hotel Porin, a reception center for asylum seekers in Zagreb, but police have been silent regarding his identity and whereabouts.

Were Smugglers involved?

According to Gordan Duhaček/Index; there is only one scenario in which the Croatian police might not be guilty of expelling Eboh and Abijah. Suppose that the Nigerian students went to the sports competition in Pula with the sole intention of staying illegally in the European Union after their six-day visa expired. Like most migrants, they don’t want to stay in Croatia, but want to go to one of the larger and more economically successful EU member states, so they paid smugglers, who are undoubtedly working throughout the region, to transfer them to Italy or Slovenia, i.e. to the Schengen free movement zone in the European Union.

Sources have confirmed that the students' arrived at the competions without rackets or sports equipment and lost every match. However, Hajdi Karakaš/Jutarnji List reports that other competitors considered them to be good-natured and pleasant to be around.

Smugglers Often Deceive Migrants

As Duhaček points out, there have been many reports of smugglers deceiving their "clients" and not taking them to the destinations they had promised. In that context, it's possible that the Nigerian students paid smugglers to take them to Slovenia or Italy but were tricked and brought to the Bosnian border. There the smugglers told them to walk through the forest where they would reach Italy or Slovenia.

Of course, Eboh and Abia followed instructions, and only when they came across migrants at Velika Kladuša did they realize that they had been duped and taken to Bosnia instead. There, they heard stories from other migrants about the aggressive pushback policy implemented by the Croatian police. That policy, as reported by The Guardian and other media outlets, involves bring migrants in vans back to the Bosnian border and illegally expelling them there under the threat of violence. With that information, they theoretically constructed the story they have shared Bosnia portal Žurnal and other media outlets.

Apparent Lack of Border Control

But even if that’s what really happened, it remains unclear how it was possible for a smuggler to take the Nigerian students to the Bosnian border, a border monitored 24 hours a day by drones, thermal cameras and thousands of police officers, and remain completely undetected.

In other words, the only scenario in which the Croatian police are not guilty is the same scenario in which the Croatian police are utterly incompetent, according to Duhaček.

Another Scenario Which Implicates Both Parties

Another possible scenario, which would involve wrongdoing by MUP and the Nigerian students, has the Nigerian students leaving their passports somewhere (or with their unidentified friend) after checking out of the HI Youth Hostel and setting off for Slovenia or Italy without travel documents. Croatian police intercept them somewhere outside of Zagreb and take them for illegal migrants, particularly after they were not able to furnish their travel documents. The Croatian police then put them in a van with other illegal migrants and forcibly expel them at the Bosnian border.

According to this second scenario, Eboh and Abia understand that admitting that they had set out for Slovenia or Italy without travel documents would identify them as illegal migrants regardless of the conduct of the Croatian police, perhaps compromising their chances of being granted asylum. Their unidentified friend (perhaps their Nigerian colleague in Zagreb) held on to their travel documents and sent them to Velika Kladuša after learning that things had not gone as planned.

Regardless of circumstance, if Zagreb police randomly pulled two people of color off of a tram, in the middle of Zagreb, and in an area frequented by tourists from all over the world; Croatia has a much more serious problem to contend with.

For updates on this story, the activities of the Croatian police (MUP) and the migrant crisis in Croatia; follow our Politics page here.

Croatia MUP and Nigerian Students: Questions Emerge in Alleged Expulsion

Allegations of the abduction and forced expulsion of two Nigerian students to Bosnia by the Croatia police (MUP) has received wide attention in the Croatian media since the Bosnian portal Žurnal broke the story on December 3. More details have emerged, which have led to even more questions, and credibility issues are muddying the narrative.

After yesterday’s official statement from MUP regarding the alleged incident, additional details are emerging, some of which may contradict MUP claims. While the story is being covered extensively in Croatian media, most of the basic questions about this alleged incident haven’t even been addressed.

There are possible credibility issues with a member of the Nigerian group and proven credibility issues with MUP. No witnesses have come forward to corroborate the Nigerian students’ allegations. One member of their group claimed asylum in Croatia on November 27, which may help support the MUP claim that people from third countries are using sports competitions to enter the EU.

However, several world news organizations have disproven MUP’s repeated denials of an aggressive pushback policy toward illegal migrants. Here’s what we still don’t know.

What was the groups’ actual flight itinerary?

According to MUP, the group of five Nigerians, one leader and four students, arrived in Croatia on November 12. The leader and one student departed Croatia via the Zagreb airport on November 17. The students claim that their return flight departed on November 18, which meant that they had arrived on the same flight with the others but wouldn’t be returning to Nigeria on the same flight.

What Zagreb hostel did the students check into?

MUP has not provided the name of the hostel and the students claim that they don’t remember the name, as they had just checked in, before setting off on a stroll through the city.

What date did the students check into that unidentified Zagreb hostel?

MUP claims they checked in on November 16, rather than November 17, as the students claim. Alberto Tanghetti, the organizer of the 5th World InterUniversities Championships in Pula supports the students’ claim and indicated that the students left Pula for Zagreb on November 17 to make their November 18 flight.

Are there any witnesses to the students’ alleged abduction by Croatian police on the Zagreb tram?

The sight of police removing the students from a tram in a large busy city for no apparent reason (they weren’t disturbing the peace) would have produced witnesses. So far no one has come forward.

Who sent the students their passports?

In yesterday’s statement, MUP claimed that the students checked out of their Zagreb hostel on November 18 and took their passports and belongings with them. However, sources now confirm that the students didn’t have their passports with them when they entered Bosnia. An unidentified friend from the competition sent the students’ passports from the unidentified Zagreb hostel to Bosnia. The students received their passports on November 25, nine days after their alleged abduction and expulsion from Croatia.

Where is the students’ luggage?

If the students weren’t allowed to return to the unidentified Zagreb hostel, the hostel would have had their luggage as well as their passports. They would have packed for a five-day trip. Where is their luggage now?

Why would the Croatian police expel the students to Bosnia, when it would have been much easier, and legal, to allow them to catch their return flights to Nigeria?

It would have been very easy for the Croatian police to physically go with the students to the unidentified Zagreb hostel and confirm they were registered there. In addition, by law, every traveler visiting Croatia must furnish their passports to the front desk (or host) of their accommodations upon arrival, as part of the registration process. That information is reported to MUP, so they should have been able to confirm where the students were staying. Why would the Zagreb police detain the students for hours, for no apparent reason, and allegedly send them in a van to Bosnia? Furthermore, in an interview for Index, Željko Cvrtila, an experienced criminologist, emphasized that the Croatian police could have only legally deported them back to Nigeria, as they had valid visas for their stay in Croatia.

If MUP has no record or evidence that the students crossed the Bosnian border, what does that say about the effectiveness of the MUP effort to control the border?

If MUP has no record of the students’ whereabouts and was not able to intersect the students’ illegal and forced expulsion into Bosnia, it would seem to suggest that Croatia still lacks effective tools, surveillance and manpower to monitor and control illegal movement across the border.

Are there any witnesses who can corroborate the students’ arrival and length of stay in Bosnia?

According to the students, they were abducted by Zagreb police on November 17 and taken in a van to the Bosnian border with a group of illegal migrants. That also means that they have allegedly been in Bosnia for 2 ½ weeks.

Is there additional information on the fourth student who sought asylum in Croatia?

According to MUP, the group leader and one of the four students returned to Nigeria on November 17. Another remained in Croatia and tried to enter Slovenia twice, but was denied entry because he did not have a Schengen passport. MUP claims that he reported his passport lost on November 18 and refused an alleged offer from the MUP central station in Zagreb to contact the Nigerian embassy on his behalf. On November 27, the student returned and filed a claim for asylum and is currently being housed in an asylum center in Zagreb.

Did the students perform competitively at the 5th World InterUniversities Championships?

Zoran Ničeno, Director of Border Security, claims in an interview with Dnevnik Nove TV that they had confirmed with organizers that the students fared very poorly at the 5th World InterUniversities Championships and lost every match. He then implied that they may not have been professionally trained for the sport and were simply using the competition as a way of entering the EU. While varied resources and levels of training can produce performance gaps among contestants in international competitions, videos of the students at the event might reveal their proficiency in the sport they flew to Croatia to compete in.

What about MUP’s claims that the students may have been involved with illegal smugglers?

In the same interview, Ničeno claimed that they have information that the students may have been involved with illegal smugglers. What evidence do they have to support that claim?

Did Bosnian officials offer to help the students return to Nigeria?

Ničeno also claimed that Bosnian officials offered to help the students return home to Nigeria, but they allegedly refused and expressed a desire to return to Croatia and apply for asylum. Did this help offer include buying them one-way tickets home? Bosnian official have not confirmed Ničeno's claims.

Follow our Politics page here to stay updated on this story, MUP activities, and the migrant crisis in Croatia.

Croatia MUP: Deported Nigerians are Lying According to Police

Croatia MUP representatives released a statement today regarding the Nigerian students who had reported to the Bosnian portal Žurnal that they were arrested by Croatian police in Zagreb, forcibly taken to Bosnian border and then left there.

Police Claim They Didn’t Act on Skin Color

Croatian police have dismissed those allegations, according to their statement as reported by Index on December 4, 2019.

"Claims that Croatian police acts and condemns individuals on the basis of their skin color are unacceptable and we strongly reject them! The police have verified the accusations of the alleged treatment of the Nigerian nationals in Zagreb on November 17. On November 18, they properly checked out of their hostel in Zagreb with their documents and left," they claim.

The police also announced what they have learned about the case so far.

"The Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Croatia have reviewed the allegations made publicly on the Bosnian portal Žurnal, and have determined the following through their research:

- On November 12, five Nigerian nationals entered Croatia, legally and according to proper procedures, to participate in an inter-university competition in Pula. The group consisted of a team leader and four participants.

"The team leader and one participant legally left the Republic of Croatia via the Zagreb Airport, after competing," MUP reported.

Conflicting Accounts of Documents Loss and Dates

Police also say Nigerians checked out of the hostel a day later than they were allegedly expelled from the Republic of Croatia.

"The two Nigerian nationals, who are being mentioned in the Bosnian media, left for Zagreb a day earlier than the rest of the group, and stayed in Zagreb. Therefore, they checked into the Zagreb hostel on November 16 of this year. On November 18, they checked out of their hostel and went to an unknown destination, after paying their expenses and taking their travel documents and personal effects with them.

Therefore, its entirely inaccurate, and we reject the allegation that their documents remained in the hostel, and that police officers of the Zagreb Police Department had acted inappropriately against them. We call attention to the contradictions in their statements and their allegations about how the police officers allegedly dealt with them on November 17. The fact is that they appropriately checked out of their Zagreb hostel on November 18 (a day later). The police had no record their legal departure from the Republic of Croatia, nor did police officers working in the field of illegal migration deal with people with these names," MUP added.

Fifth Participant Tried to Enter Slovenia Twice

MUP also wrote about the group's fifth participant, whose visa expired while he was in Croatia. He received a judgement to leave the European Economic Area (EEA) within 14 days.

"Regarding the fifth participant in the group, it was determined that he left his accommodation in Pula on November 17 of this year. He tried to leave the Republic of Croatia and enter Slovenia at two separate border crossings. On both occasions, Slovenian border police officers denied him entry because he does not possess a Schengen visa. Following these two attempts to cross the border, the Nigerian national arrived at the Central Zagreb Police Station on November 18 and reported the loss of his travel documents. He was offered the option to contact his embassy but refused.

Then He Applied for Asylum in Croatia

Given that his visa had expired on 17 November of this year, he was issued a judgement to leave the European Economic Area (EEA) within 14 days, following an administrative procedure. However, the Nigerian citizen did not leave Croatia, but returned to the Central Police Station in Zagreb on November 27th and expressed his intention to seek international protection in the Republic of Croatia. He was granted protection status and is currently in the Asylum Seekers' Asylum Reception Center in Zagreb. It is important to note that, on this occasion, he presented the travel document which he had previously reported lost," they added.

Police claim that third-country foreign nationals are using legal entry into the Republic of Croatia to attempt to move further to the EU after participating in the activities for which the permits were obtained.

Using Sports Competitions to Enter EU Illegally

"All of the Nigerian nationals had their return tickets for November 17 of this year. Two of them used their air tickets and left Croatia on that day, while the remaining three missed their opportunity to leave Croatia legally. This fact casts real doubt on the intent of their arrival and stay in Croatia.

Police officers had been encountering abuses of alleged and real participation in sports competitions in Croatia during their elevated campaign in the fight against illegal migration. Entering Croatia legally and participating in an approved sports activity is one way for foreign nationals from third countries to continue their journey illegally to their target destination countries in Europe.

The Republic of Croatia has refused entry to nine Nigerian nationals at border crossing this year due to non-compliance with conditions for entry.

Police officers will continue to investigate the allegations and review available facts in this case to determine whether this is another case of abuse of sports competitions for the purpose of illegal migration," MUP concluded.

Follow our Politics page here to keep updated on the migrant crisis in Croatia.

Croatian Identity Theft: Documents on Black Market Due to MUP Chaos

Croatian national security is at stake because criminal organizations have infiltrated the MUP identity document issuing system, which stores the personal information of Croatian citizens and residents, according to Željko Cvrtila, a national security expert and former police chief.

"Low wages, lack of internal oversight, political recruiting, and the interference of politics and money within MUP (Croatia Ministry of the Interior) are the main reasons for the appearance of Croatian identity documents on the illegal market," he added during a brief interview to Renata Škudar/Nacional on November 29, 2019.

Is Croatia's national security at stake?

“This is endangering national security, because Croatia’s document issuing system has been infiltrated, and a lot of original identity cards and passports have fallen into the hands of criminal organizations. The system has been penetrated because the intelligence and security networks in our neighboring eastern states are connected to criminal organizations in these countries and with criminal groups in Croatia. All of this is happening on Croatian territory and that is our biggest problem."

How did so many Croatian documents appear on the illegal market?

"The MUP system is intertwined with various political lobbies and people who are not subject to internal oversight. Procedures are not being properly implemented and the people in charge of these systems are not doing their jobs. There is a lack of oversight regarding employee resources and criminal organizations can easily exert their influence in such a permeable system. The system only works when corrupt politicians and the mafia aren't interfering in politics and business, or providing and returning favors. Otherwise, we’ll have chaos where crime reigns,” concluded Cvrtila.

Read an EU national’s account of MUP abuse here. Find out how to change your address at MUP here. Follow our Lifestyle page here and our Politics page here for updates on MUP and the activities of other branches of Croatian government. The MUP website can be accessed here.

Responsible Member State? Emotional Abuse by MUP Towards EU National

November the 7th, 2019 - Croatia has been a member state of the European Union since July 2013. Some growing pains were expected throughout the following year, maybe two. The new system which allows ease of access to life and work in Croatia for other EU nationals of course takes a little time to implement, MUP's administrative staff need to be updated, and so on.

Mistakes happen, and misunderstandings occur. EU law, however, is not complicated, and if you're employed in a position which demands you know it, and keep up to date with it, it's quite unexpected to be told, as an EU national (Netherlands), who was a former Croatian national on top of that, that you have ''no rights''. Amazing, no? Welcome to Croatia, the country set to preside over the EU at the beginning of 2020.

We at TCN do our best to help out foreign nationals (be they from the EU or outside of it) when it comes to residence and citizenship matters, and it's always amazing how many comments and emails we get from various people stating how their experience was very different to what both EU and Croatian law prescribe. We've read tales of nothing less than abuse, and while all such stories are utterly unacceptable, one such example among the thousands (literally), was from a former Croatian national, who is now a Dutch national, who had recently moved back to Zagreb - and it stood out from the crowd for all the wrong reasons.

The Dutch citizen in question wanted to get her Croatian citizenship back, but of course, she first sought legal residence, and as a Dutch national, she had every right to do so and have it all done and dusted without much fuss. However, she was instead belittled, demeaned, shouted at like a child, reduced to tears, told she had no family and also that she has no rights. We're keeping this woman's identity anonymous as per her perfectly understandable request after such an inexcusable experience at the hands of the Croatian authorities, but thanks to her unwillingness to just conform, SOLVIT, an EU body which helps mistreated EU nationals got involved, and not long after, so did the European Commission.

Here is her story of psychological abuse and public shaming by MUP. The disgraceful treatment she received at the hands of administrative clerks at the foreigners' department at Petrinjska police station, in the very heart of Zagreb has attracted the attention of the EC.

''I’m a foreign Croatian national who migrated to the Netherlands 13 years ago. After completing my masters and PhD in Amsterdam, I moved to the UK to do my postdoc at the University of Oxford, and went on to work for the London office of a large multinational company. I’ve recently returned to Croatia with the intention of staying permanently.

On the day after my arrival, I went to the Ministry of Interior Affairs (MUP) in Petrinjska to inquire on how to apply for temporary residence. As a Dutch citizen, I am technically not obliged to do this for the first 3 months of my stay, but it’s necessary for a whole host of practical reasons, e.g. I can’t register or drive my car without it. Because I’m well familiar with the fact that the documents required by the clerks can (and often do) differ from what is stated on the website, I went to Petrinjska in person to obtain a list of documents needed to apply. After an hour and a half long wait, I obtained the following list (which differs from what is on the website indeed, and I’m copying in its entirety in case it’s helpful to anyone):

- Form 1b

- Copy of a passport

- Proof of funds or a work contract

- Proof of health insurance

- Rental contract certified by a notary, or a landlord’s declaration signed at PUZ (can also be certificate of ownership)

I later found out only three of the above documents are required by law (passport, proof of funding, and proof of health insurance). Also, it struck me as bizarre that I had to wait 1.5 hours to obtain information that should so evidently be provided on MUP’s website. It made me wonder how much of the (enormous) queue was caused by the fact that zero of the process is digitised at the moment (my bet is almost all of it). But I went home and prepared all the documents listed above.

The following day I came back at 9:30 and waited for two hours, in which the line moved only by 10 numbers (I was 60 numbers away). Realising that I would not be up before the end of the working day, I left and decided to get up at 6 the following day so I can come back to Petrinjska at 7:45 to take my place in the queue. There were 50 people in the line before me when I got there, but thankfully they were not all waiting in the same counter and I did not have to wait too long. I handed over all the documents required above.

The clerk inquired why I needed the residence card. Assuming the meant what my immediate need for the card was, I replied that I needed to register my car. She said that was not a valid reason to reside in Croatia. Realising her original question was why I was in Croatia, not why I needed a card, I briefly stated why I was here (not expecting to be asked as it’s not on the above list, and not really knowing what aspects of my stay were relevant – is it relevant that I’m getting medical treatment in a private clinic, is it relevant that I’m following some courses, is it relevant that I’m planning to stay permanently?).

I inquired for a list of valid reasons to apply. The lady at the counter raised her voice and demanded that I left. I wasn’t really inclined to do that after having spent 7 hours on this up to that point, especially while knowing that information provided on websites often differs from what the clerks actually ask for. Several pieces of information I managed to gather from the clerk’s yelling that ensued were, for example, that some of the valid reasons to apply included family reunification, studying, or selling a property. Since the latter two reasons didn’t apply to me, I asked whether family reunification could somehow be applicable to me.

They asked what family I had here. With dozens of other people within hearing distance, I shared with her that I lost both my parents and my brother, and that I have a cousin whose family I am very close with. The clerk replied that I cannot reunite with family, since I don’t have one.

Throughout the whole process, I found it very odd that I was being asked for a reason of stay, since a) it was not told to me upfront (despite me making a dedicated trip the day before for that very purpose), b) I’m an EU citizen and I’d never had that problem with any other EU country. I found it especially odd that the rules communicated to me by the clerks seemed a lot like regulations for third (non-EU) country citizens. After repeatedly asking for a list of valid reasons to stay (at this point we’d already spent 15 minutes on this, with dozens of other people waiting in line), the only advice I managed to get was to read the Croatian Law for Foreign Nationals.

This is what I did; as initially expected, the law was very clear: I should be able to apply for temporary residence very easily and with minimum red tape. I spotted the following five inconsistencies between the law and the information communicated to be at MUP:

MUP: I was already once granted residence under ‘other purposes’, and I cannot reapply.

Law: I can apply under ‘other purposes’ multiple times.

MUP: If I had a valid reason to apply (which according to them I do not), I could only apply to reside in Croatia for a year.

Law: I can apply for a 5-year temporary stay, after which I can apply for permanent residence,

MUP: If I had a valid reason to apply, I could in theory apply on the basis of undergoing medical treatment, family reunification, or study.

Law: there are 4 valid categories of reasons to apply: work, other purposes, study, or reunification with an EU family member residing in Croatia (note: this is different to reunification with Croatian family members that the clerks listed).

MUP: I need to provide the five documents listed above.

Law: I only need to produce a copy of my passport, proof of funds, proof of medical insurance, and a filled-out form.

MUP: I was obliged to register a tourist stay on the day I landed in Croatia. Law: This fundamentally does not apply to EU nationals.

After this initial interaction with the clerks (and before reading the Law on Foreign Nationals) I left the counter really shaken; I’m not used to being yelled at and found the whole experience really distressing, especially as I remained polite throughout the interaction despite the clerk’s attitude. I started to think about things more calmly and realised that perhaps my ongoing medical treatment could be a valid reason to apply; I went back to verify and got confirmation. After contacting the clinic I am being treated in and getting a nurse, a doctor, and a lawyer involved in producing a document for me, I found out I was mis-informed by MUP and that medical treatment is not on the list of reasons to apply for EU nationals.

The highlight of the day occurred after I had read the Law and returned to the counter with correct information at my disposal (this was already 6 hours into that day’s visit to MUP).

I told the clerks I had read the Law as advised, and tried to tell them that the information I was given by them was inconsistent with the Law on several points, and that according to EU regulations I appeared to be entitled to submitting a residence application. What followed can only be described as verbal abuse. The clerks did not let me finish; instead, one of them suggested I wrote a complaint, which would then be rejected (“you can put all this in a complaint, and we will reject it”).

The other pointed out to people in the queue behind me that I was returning for the fifth time that day, and taking up time that should be theirs. They referred me to their superior (which witnessed our first exchange and was unfortunately unfamiliar with the law as well; he supported the clerk throughout our conversation). I waited for this gentleman for 45 minutes, and he then informed me that I was wrong and am not entitled to apply. I pulled out my mobile phone and showed him the relevant section in the Law on Foreign Nationals.

He was still not convinced, but luckily two of his co-workers had entered his office at that point, and he asked them to stay while I present my case to them. I did, and both of them immediately said I was right and am entitled to submitting a residence application.

At this point I started to cry; I was overwhelmed by everything that had happened that day and in the two days before. I told them I was not sure how to actually submit my application, as they would not accept it at the counter. One of them walked me to the counter and explained to the clerks that they needed to accept my application. After a 12-hour process spread across three days, I had finally managed to submit my application. The waiting time for resolution is 5-6 weeks (during which I cannot drive, and living on a hill without public transport this practically means being trapped at home).

While waiting at MUP, I reported the whole case to European Commision’s SOLVIT system (and I strongly encourage other EU nationals to report similar violations; the system was designed to address exactly these type of situations: 'Unfair rules or decisions and discriminatory red tape can make it hard for you to live, work or do business in another EU country.' https://ec.europa.eu/solvit/).

I also inquired with the clerks about who oversees their work, but the only response I got from them was ‘Madam, we’re the Ministry of Internal Affairs’, implying that they don’t report to anyone. I believe there is a large-scale problem in Croatia with adherence to EU laws (I was persistent enough and spoke the language so was ultimately able to get the application accepted, but many are not lucky enough). This is a systemic problem and is highly prevent in the Ministry of Internal Affairs, as evidence by the fact that even the senior supervisor on the floor denied me the right to submit a residence application.

The clerks’ abusive attitude is a separate problem and I believe it needs to be thoroughly addressed as well. Sadly, the vast majority of Croats are accustomed to this kind of treatment and consider it standard; I think it is very important that they understand it is not, and that they are entitled to fair treatment and correct information. I would encourage anyone who has experienced a similar treatment to come forward, whether to the media or to relevant EU institutions.

Update: SOLVIT quickly responded with the following:

''Dear ___,

Thank you for your message. My apologies for all the distress you have experienced. Indeed it sounds like they have treated you unfairly. Unfortunately since you have managed to submit your residence application and have it accepted, you do not have a concrete problem anymore. This means that we are unable to intervene, because we can only help when there is a concrete problem for the applicant. Since we believe it is important that you notify the treatment you have experienced, we would like to suggest to hand in a complaint through the European Commission. You can find out more information through (a link they provided).

They are able to look into complaints concerning situations that have already occurred and have already been resolved.''

As per their advice, I forwarded my complaint to European Commission, who is now looking into it. In the meantime, after nearly a 5-week wait and having to submit another document not formally required by law (proof of ownership of my apartment, which under Article 161 of the Law on Foreign Nationals is not required), I got my temporary residence approved. I now need to wait an additional three weeks to get my residence card. After noting to a clerk at MUP that this seems quite long, he informed me I was “very lucky”, as “people often wait 2 months”.

I sighed and noted that Croatian bureaucracy is quite bad, adding that this was not his fault personally. He responded that after I got my citizenship (which I have no intention of applying for, but I guess he assumed this was something I wanted to pursue) I would be able to complain. I replied saying that EU nationals have rights, too. His response was: “No, you don’t”.

Can you believe that, just think about it for a second. A public servant in an EU country tells an EU citizen that they have no rights in Croatia.

I will quote here Article 153 of the Law on Foreigners: ''(1) A national of an EEA Member State and members of his or her family, whether or not they are nationals of an EEA Member State and who have the right of residence in the Republic of Croatia, shall be equal to the citizens of the Republic of Croatia under the provisions of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.''

I did not explain the law to the gentleman, because given his position he should have known it (at least the basics; this is the first article of the section on EU nationals in Croatia); I just told him that we still have rights, despite what the MUP's staff think.''

If you are an EU national and you have experienced similar issues or feel you have been mistreated, given the incorrect information by MUP, publicly, verbally abused or shouted at, we at TCN urge you most strongly to report the issue to SOLVIT and to the European Commission.

SOLVIT deals with unresolved cases and you can click here to report your issue.

The European Commission investigates such issues which have already been resolved, and you can report your issue here.

If you'd like us to tell your story, email us at: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. We have been collecting experiences across various expat groups and beyond, and we intend to write an article including all of them. The response was overwhelming, and the stories of abuse, misinformation and mistreatment are rife. As stated, we intend to publish them all and forward the article to the European Commission, who is now investigating the case described in this article.

For more information and help on residence and citizenship, follow our dedicated lifestyle page.

MUP to Place More "Super Cameras" Along Croatia's Roads

As Poslovni Dnevnik writes on the 30th of September, 2019, the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MUP) will acquire sixteen new fixed cameras and speed control devices, 28 cases/cabinets, 24 manual, and 18 stationary speed measurement devices next year, Vecernji list reported on Monday.

This year, the Croatian police installed 59 new fixed cameras to monitor the speed of vehicles and 122 cases/cabinets in which these devices are installed. In addition, in 2019, 76 manual and 32 stationary devices for measuring the speed of movement of vehicles were purchased, which, according to MUP, will also submit images to the central server and process them through the OEP application, as stated by the aforementioned article from Vecernji list.

Back in 2010 and then five years later in 2015, the Ministry of Internal Affairs acquired 28 fixed speed monitoring devices and placed them at 62 locations, also with their accompanying cases/cabinets, meaning that 87 speed monitoring cameras and 184 accompanying cases (which will have their cameras replaced) have been installed along Croatian roads to date. The sixteen new devices which MUP will introduced along Croatia's roads next year, that figure will reach 103 fixed cameras and 212 cases/cabinets.

The brand cameras set up by MUP, in addition to catching speeding offenses, can catch drivers in other offenses such as the improper use of mobile phones, not using a seatbelt, and improper overtaking.

The system operates as a Doppler radar, so the devices measure two oncoming traffic lanes and two leaving lanes at the same time. They also have the ability to automatically read the vehicle's license plates, as MUP explained.

According to the police, by September the 19th this year, around 50,000 traffic violations were detected by road cameras along Croatia's roads, and they typically related to improper or illicit speed, Vecernji list reports.

Make sure to follow our dedicated lifestyle page for much more. If you're interested in the rules and regulations of driving in Croatia, as well as learning a few tips, check out our dedicated page on the matter.

Expats in Croatia: How to Change Your Address at MUP

September the 27th, 2019 - Croatia doesn't like change. It doesn't like the idea of being dragged into the 21st century either. If you're wondering how to go about respecting the law and altering your address, read on.

I've written many articles on residence permits, citizenship through descent, marriage, naturalisation and special interest, work permits, Croatian and EU immigration law - basically bureaucracy galore.

In this beautiful country full of outdated websites and unelected government officials (the women are ''affectionately'' known as šalteruše) who can't keep up with the constantly changing laws or even manage a smile on the best of days, it's no wonder that Croatia's increasing number of foreign residents need a little helping hand from time to time.

Changing your address should be a simple affair, and in just about everywhere else, it is. You can likely do it online in a few clicks or you don't even need to do it at all. Ah, freedom. Not in Croatia, however. If you're a foreign national and you hold a valid residence permit (either temporary residence/privremeni boravak or permanent residence/stalni boravak), and you've moved house, you'll need to notify the police.

Sarcasm aside, there has been a helpful little system set up called e-Građani (e-Citizens), which allows you to undertake many of the mundane tasks which used to always involve going to various offices in person armed with an array of personal documents and petty cash for tax stamps. But, of course, this doesn't work for everyone, so you'll need to do it in person.

If you have approved legal residence in Croatia and you move to a new city, you'll need to notify the police in your new city (at the administrative police station responsible for your area), of your arrival, and register your address there if you intend to stay there for more than three months consecutively.

In Croatia, you can have two addresses (yes, let's complicate things for no reason even more), one of them is called a boravište, and the other is called a prebivalište.

A boravište is a place where a person will be staying temporarily, but has no intention of permanently staying there. In that case, you don't need to register your boravište if you don't plan on staying there for more than three months in a row (as mentioned above).

A prebivalište is a place where a person plans to stay permanently, to live their lives (this includes exercising their rights, working, having a family, etc etc). If you've changed your prebivalište, then you'll need to report it to the police at the administrative station responsible for the area your address is in.

If you live in Croatia legally, you're obliged to report any changes to your address to Big Broth...sorry, I mean MUP.

The law states that you need to report your change of address within fifteen days, however, if you hold temporary residence, you need to register your new address within three days of you having arrived there. If you hold permanent residence then you need to do it within eight days. Is this law always followed? Honestly - no, it isn't.

More often that not, you won't be asked about when you arrived at your new place, particularly if you're an EU citizen. I'm not advocating that you break the law, but this stipulation is difficult to come by if you don't speak Croatian, so just don't volunteer that information if you realise you've unknowingly gone over that time period, unless you're specifically asked.

If you have a rental contract which stipulates specific dates, then simply make sure to report your change of address within the time period prescribed, so as to avoid any potential headaches or even fines from the police.

THE PROCEDURE:

You'll need to fill in an ''application form'' to change your address (yes, really, it's called form 8a) for foreigners which you'll be given when at the police station responsible for your area.

You'll need to provide the correctly filled in form with your new address on it.

You'll need to provide your passport and/or your government issued ID card, as well as your Croatian ID card.

You'll need to provide a rental contract (notarised) or a certificate of ownership, a purchase contract, a gift contract, or have your landlord/the person legally responsible for your address come with you to the police to sign a document confirming the whole situation is indeed real.

The administrative clerk will then stamp your filled in application form.

You'll then need to have a new ID card made with your new address on it. So, that will involve having a new photo taken and paying the small administrative fee of (what is currently) 79.50 kuna. Your new ID card will typically be ready in about three or four weeks. Oh, and you'll need to come and pick that up in person, of course.

It's worth noting that some people have been told that they don't need to update their ID cards. This is a grey area, with some administrative police stations asking you to do this, and some not. In any case, it is what MUP in Zagreb prescribes and you absolutely should have an updated address on your current ID card so as to avoid administrative issues, and indeed issues with the police.

Please note that changing your address is not a new residence permit application, but the requirement for a new residence card to have your current address on it is simply a formality and its validity will remain the same.

Don't be surprised if the police come to check that you really do live at your new address. However, this is happening less and less frequently, especially for EU citizens.

While it seems extremely outdated to many that time often needs to be taken up by visiting MUP in person and filling in forms as opposed to the wonderful digital process (which Croatia isn't a fan of) of doing it all online, it's worth knowing the ins and outs of what should be a very simple formality.

We hope this helps you if you've changed your address and aren't sure what steps to take next to stay on the right side of the law.

Follow our dedicated lifestyle page for more.

Unsatisfied and Underpaid Croatian Police Ready to Strike?

There is a lot to be said about the taxes in Croatia, and how much net income is reduced when taxes and contributions are taken off it. This is a burden not only for the employee, but for the employer, who must add on an eyebrow-raising amount when paying an employee in order to make sure they get their negotiated net amount every month.

The need for a general raise in wages for all sectors, as well as the lowering of taxes, are two of the very few things almost everyone in Croatia can actually agree on, and some are making a stand and taking things into their own hands. The Croatian police included.

As Poslovni Dnevnik writes on the 27th of August, 2019, Croatia's nurses, doctors, teachers, and police officers are not happy with the wages they're taking home every month, and they are ready to strike in order to drive their message home and finally create some change, at least that's what the Police Union announced, which celebrated its twentieth anniversary just recently.

Appearing on RTL Direct (Direkt), the one man who has been the president of the Union for all of those long twenty years, Dubravko Jagić, said that a wage increase for Croatian police officers as of January 2020 has been tentatively agreed with the Government of the Republic of Croatia. But, there is, as always - another but.

"If we don't manage to stick with that agreement, then there's always the possibility of going on strike. We would like to avoid that because it could have untold consequences and I'm sure that the government will be understanding.However, we can strike in a slightly different way from our colleagues from other ministries," said Jagić, explaining that he was referring to a white strike or an ordinary strike, and concluded that the Ministry of the Interior (MUP) had the least problem of all in organising some form of strike within a mere 24 hour period, that would cause total chaos.

Make sure to follow our dedicated lifestyle page for much more.

Lika Entrepreneur Partners Up With Croatian Ministry of the Interior

As Poslovni Dnevnik writes on the 27th of August, 2019, when asked what the secret of his success is, the well known Lika hospitality entrepreneur replied: "I have no objections, these are good people and they're good guests."

The most well known and successful tourism and hospitality entrepreneur from the Lika region - Željko Orešković Macola, has turned his talented hand to a new business.

To be more specific, last year, a campsite with a swimming pool and fourteen bungalows was opened, as were about twenty campsites intended for guests from all over the world.

Macola soon turned to no less than MUP (Ministry of the Interior), in whose tender he received accommodation for their border guards. Another two houses in Korenica house sixty of MUP's border guards, and next week, Macola is all set to launch a new tourist settlement located in Vranovača, near Korenica, which will also be filled up with police officers.

Macola doesn't want to talk about the numbers, as he doesn't want to bring any discomfort to his partners, who in this case are MUP.

"Oh, forget about the numbers, they pay per police officer, I don't know how much they pay exactly, but they do pay fairly," Macola told Jutarnji list briefly.

However, if his capacities are summed up, the number of MUP officers he receives can easily be reached, and soon that figure could increase to as many as 200 of them.

Police vans bring them all year long, which is why Macola, after all, went to the MUP to enter the public tender in the first place.

They got a good home in Grabovac, because they've been there almost the whole year. They spend their daily breaks in the pool and the restaurant next to it.

It was at this camp that Minister of the Interior Davor Božinović, together with the chief of police Nikola Milin, recently boasted of an operational location for coordinating the work of police forces, presenting equipment and techniques used in the daily surveillance of the state border, ie, dealing with and the detainment of illegal migrants.

Make sure to follow our dedicated lifestyle page for much more.