Rijeka City Museum Nominated for Title of European Museum of the Year

December 15, 2022 - The Rijeka City Museum has been nominated for the flattering title of European Museum of the Year. The competition is fierce, and the winner will be announced at the conference of the European Museum Forum in Barcelona in May 2023.

As Poslovni / HRT write, the Rijeka Museum will compete for the title of the best with 32 other European museums. This is the first nomination at the European level.

"This would be the greatest recognition and success, but being nominated is a success in itself. Even the nomination for an Oscar counts, and we already had two awards from the Croatian Museum Society," said Ervin Dubrović, director of the Rijeka City Museum. Those were for the exhibition of restored works by Gustav Klimt and Merika - an exhibition dedicated to emigration. The permanent display in the magnificent Sugar Refinery Palace also received awards. It covers two floors and thirty rooms.

In the museum, you can learn about the first torpedo in the world, the history of the theater, or the legendary rock music scene in Rijeka, which is only the beginning of the story. The home of the permanent museum exhibition has been attracting many curious visitors for two years since its opening.

"In two years, 32 thousand people visited the Palace. From the beginning, it was our fellow citizens who wanted to see the new city attraction; tourists came to the fore later," says Velid Đekić, head of public relations at the Museum of the City of Rijeka.

This is not an empty, lifeless space; quite the opposite! It breathes and lives alongside its fellow citizens; many find inspiration in the space. "The sugar refinery is a representative object that we found fits very nicely with our models, which will fit well into the space so that they can show all their beauty," pointed out Renata Štefan Barišić, a professor at the Rijeka Trade and Textile School.

The European Museum Forum will decide the best museum on our continent, and the winner will be announced in May next year.

For more, make sure to check out our dedicated Lifestyle section.

Between Two Periods of Waiting: Sisak Earthquake Aftermath Captured in Moving Photos

January 27, 2022 - Croatian photographer Miroslav Arbutina Arbe documented the aftermath of the devastating earthquake in a series of photographs currently displayed in Rijeka

It’s been a little over a year since one of the greatest tragedies Croatia has seen in recent times: the disastrous earthquake that hit Sisak-Moslavina County in December 2020.

Often referred to as the Petrinja earthquake after the town which suffered the worst blow, it ravaged other towns and villages in the area as well, affecting the lives of many.

Shortly after the earthquake, Croatian photographer Miroslav Arbutina Arbe was hired by the Ministry of Culture to document the damage inflicted on cultural heritage sites, specifically in the town of Sisak. The result is a series of 82 black and white photographs that have since been displayed in a moving exhibition commemorating the disastrous event.

While the primary purpose was damage assessment and the photos are thus documentary above all, as a skilled photographer Arbutina aptly captured moments that would have likely gone unnoticed by an average observer. A music school diploma on a wall ripped in half by tremor, handwritten notes tacked above the kitchen sink, a marital bed buried in rubble, and perhaps the most poignant, a calendar forever stuck on the fateful December 29th.

Devoid of colour, framed and displayed in a gallery setting, the photos are loaded with emotion and take on an artistic property. It’s an eerie sensation, recognising an aesthetic quality in images of devastation and loss, but this only seems to reinforce their emotional impact.

This is also reflected in the very title of the exhibition, ‘Between Two Periods of Waiting’, referring to the horrifying uncertainty that people affected by the earthquake have had to live with. As the author himself stated: ‘Those who haven’t experienced such a catastrophe probably believe that losing one’s home is the worst part of it, but it isn’t. To me, the worst was expecting the next earthquake to hit, that period of uncertainty between two quakes.’

The exhibition was conceived by the author and organised in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture, the City of Sisak and the Sisak City Museum.

The photographs were displayed in Zagreb and Sisak in late 2021, and are currently on display at the Rijeka City Museum (the 'Kockica' building). The exhibition is part of this year’s Museum Night programme in Rijeka, and will remain on display until January 29th. Entrance to the exhibition is free of charge.

Rags to Riches to Ruin: 200 Years of Hartera, Croatia’s Iconic Paper Factory

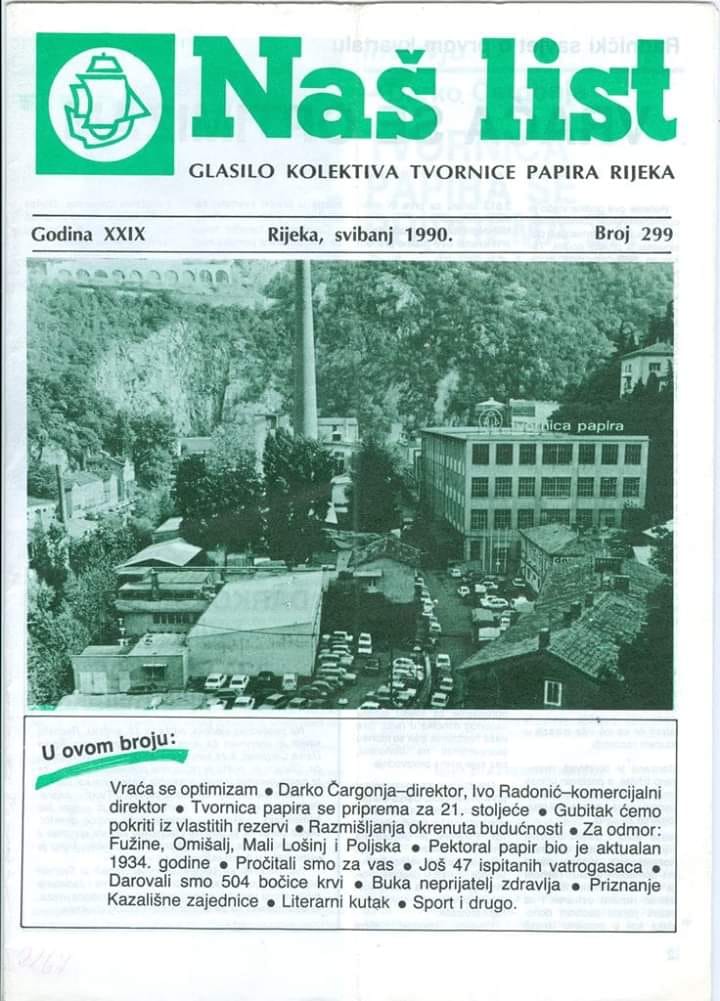

Did you know that the first steam engine in the Balkans was installed at a paper factory in Croatia? Or that the same manufacturing plant produced 7% of all cigarette paper in the world? It’s been 200 years since the foundation of the Rijeka Paper Mill, which grew into an industrial giant of international renown only to meet its demise in the early 2000s. A look at the legendary Hartera on November 29th, 2021

Better known by its nickname Hartera, the Rijeka Paper Mill used to be one of the focal points in the city renowned for its (former) industrial glory. Founded by a local industrialist in 1821 and further expanded by foreign investors, the factory grew into a wildly successful business over time. Hartera provided jobs to thousands of workers, its paper products were exported worldwide, and won medal after medal at international expos.

Alas, much like the majority of industry in Rijeka (and the rest of the country), the Paper Mill fell victim to the economic turmoil that followed after the war in the 90s. The factory ceased operating and the insolvency proceedings drew to a close in 2005.

This year marks the 200th anniversary of Hartera’s foundation, and the City Museum of Rijeka marked the occasion with an exhibition dedicated to the Paper Mill, its history and its workers. Named Hartera bez harte (paper mill without paper), the exhibition inspired this article as an homage to the legendary factory and its illustrious past.

Exhibition Hartera bez harte at the City Museum of Rijeka

The story of Hartera begins with rags.

Humble rags once used to be highly coveted goods: paper was predominantly manufactured from cloth fibers until 1886 when cellulose replaced fabric as the main substance used in paper production.

Rag trade thus became quite a prolific commercial activity in these parts. Peddlers called cunjari visited small villages and went from door to door, collecting used linen and hemp cloth which they later resold to bigger buyers. Rags were in demand worldwide, and so tonnes of old cloth sourced in all parts of Croatia got exported to Trieste, London, Liverpool and New York via the harbour in Rijeka.

Andrija Ljudevit Adamich, a trader, industrialist and one of Rijeka’s best known historical figures saw an opportunity in the booming rag trade. He purchased a mill on the river Rječina in 1821, repurposing the existing facilities into a paper mill which soon employed 21 workers.

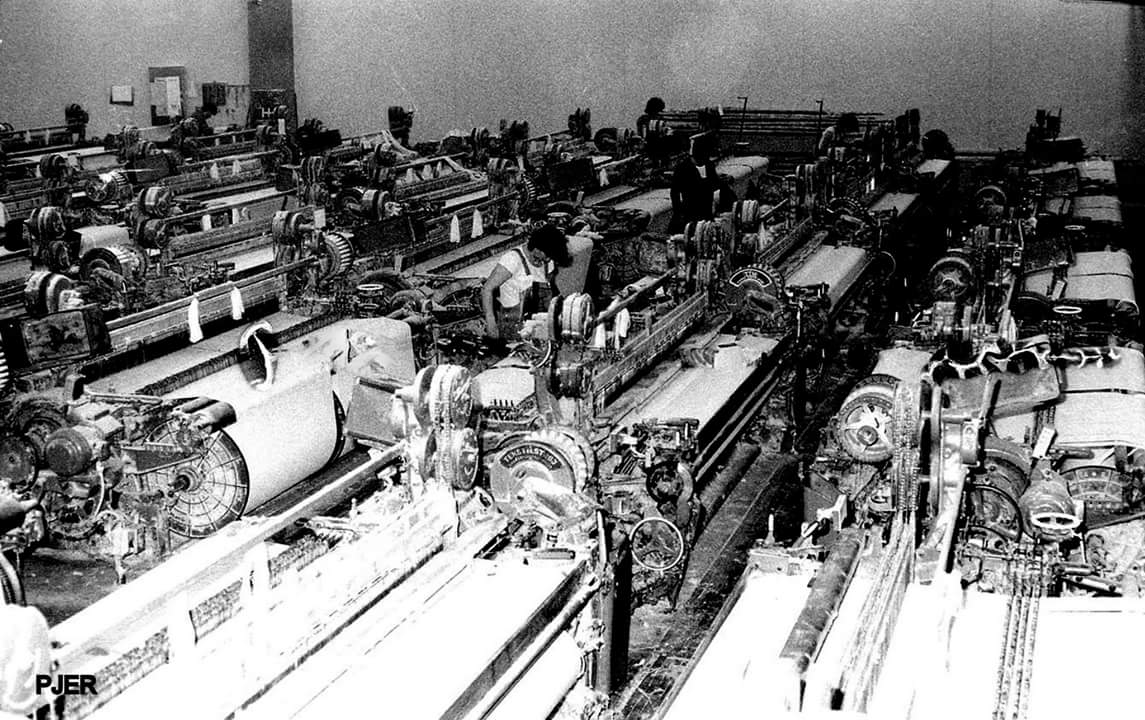

The Rijeka Paper Mill in the 20th century / Nova riječka enciklopedija - Fluminensia

The business turned out to be more of a headache than a success for Adamich. It was a time of general economic hardship, and manufacturing was made more difficult due to high production costs and procurement issues. A few years later the company was sold to foreign investors, namely Charles Meynier and Walter Crafton Smith who turned the struggling business into one of Rijeka’s industrial giants. They expanded and modernised the manufacturing plant and promptly installed a Foudrinier, the best paper making machine available at the time. Oh, and…

The first steam engine in the Balkans

Business picked up quickly after Meynier and Smith took over, and it wasn’t long until the factory employed 250 people to meet the production demand. As the output increased, manufacturing required more power, leading the owners to obtain a steam engine for the factory in 1833 - the first one in the Balkans.

It didn’t take long for Hartera paper to start amassing accolades at major industrial expos. It won a silver medal at the First industrial exhibition in Vienna in 1835, followed by awards won in Paris, Munich, London, Barcelona and Melbourne.

Interestingly enough, the company only launched its products domestically in 1878. For the first 50 or so years of operation, paper products made in Hartera were only sold on foreign markets: Italy, England, USA, Brasil, East India, and the eastern Mediterranean from Greece and Turkey to Jordan and Egypt.

Poor working conditions

While the factory might have had the best manufacturing equipment money could buy at the time, and operated with such success that its workforce expanded significantly with each passing year, working conditions were far from ideal.

At the end of the 19th century, the company employed some 600 people; the factory operated around the clock, with everyone working 12 hour shifts with a single one hour break. No workwear or protective gear was provided to employees, leading to frequent injuries on the floor.

Workers at the rag sorting hall

Hygiene standards weren’t a thing either, the rag sorting facility being the worst offender in this regard. The workers had to sort through mounds of dirty used fabric riddled with bacteria (again, without any protective gear), leading to a slew of infectious diseases.

Considering that some diseases were not yet studied or had no known cure at the time, they were often referred to by alternate names. Anthrax was widely known as the woolsorter’s disease, or in Hartera’s case, cunjavica - the ragpicking disease. In the late 1880s, a particularly severe outbreak of anthrax resulted in the tragic death of 22 women workers.

On labour rights

Fed up with the poor working conditions, workers from several factories in Rijeka got together in 1906 and staged a mass strike. All 600 of Hartera’s workers joined the strike with a few demands: they called for shorter shifts, a day off on Sundays, and a 20% raise. Additionally, they asked for an employee board to be established, composed of eight workers who would serve as intermediaries between the company owners and the rest of the workforce.

The management responded by firing them all.

Things started to look up in the following few decades, though. Several syndicates negotiated with the management, leading to a collective agreement in 1938 which saw quite a few improvements to the working conditions at the paper mill. Employees were to work eight hour shifts, six days a week, and get paid every Saturday. Men earned 5 dinars per hour, whereas women got 4,5. After two years of employment, all workers earned a right to six vacation days a year. The company was also finally required to provide protective workwear and washing facilities with cold and hot water.

Why ‘Hartera’?

The Rijeka Paper Mill was officially named Tvornica papira (paper factory), but the enterprise has more often been referred to as Hartera to this day. Where does the nickname come from?

The Croatian word for paper is papir, but is called harta in the local dialect - which soon resulted in hartera, a logical name for a place where harta was made.

Pero Lovrović Pjer / Nova riječka enciklopedija - Fluminensia

Paper production

A wide range of products was manufactured in Hartera ever since the factory first started operating, mostly various types of writing and packaging paper.

Cigarette paper was first made at the factory towards the end of the 19th century, and over time became one of the company’s most popular products. Quality was of utmost importance, and the factory even procured a tobacco blend called harman to test the rolling paper on the particular blend it was made for.

In the 1980s, Hartera accounted for 7% of global cigarette paper production.

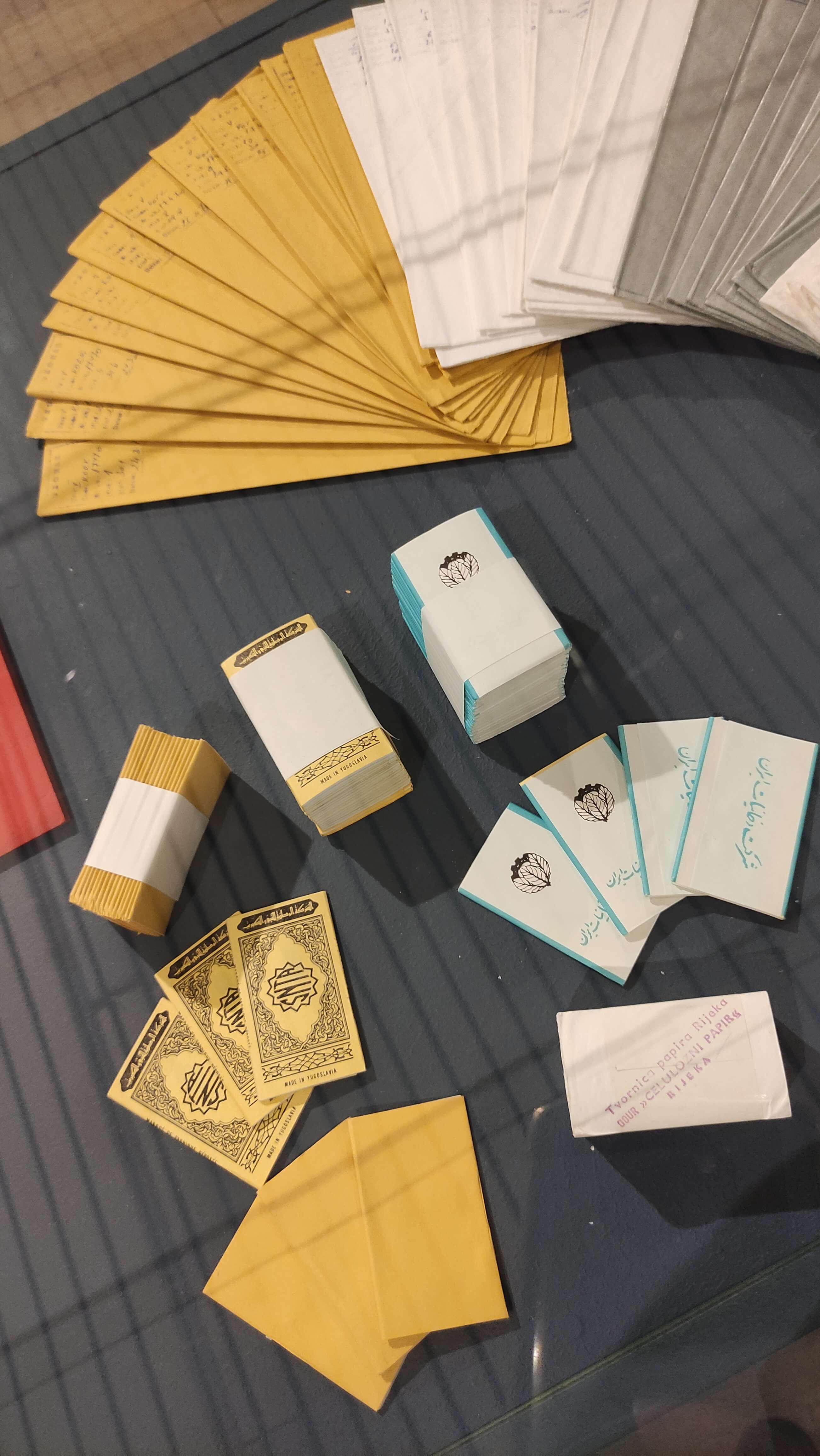

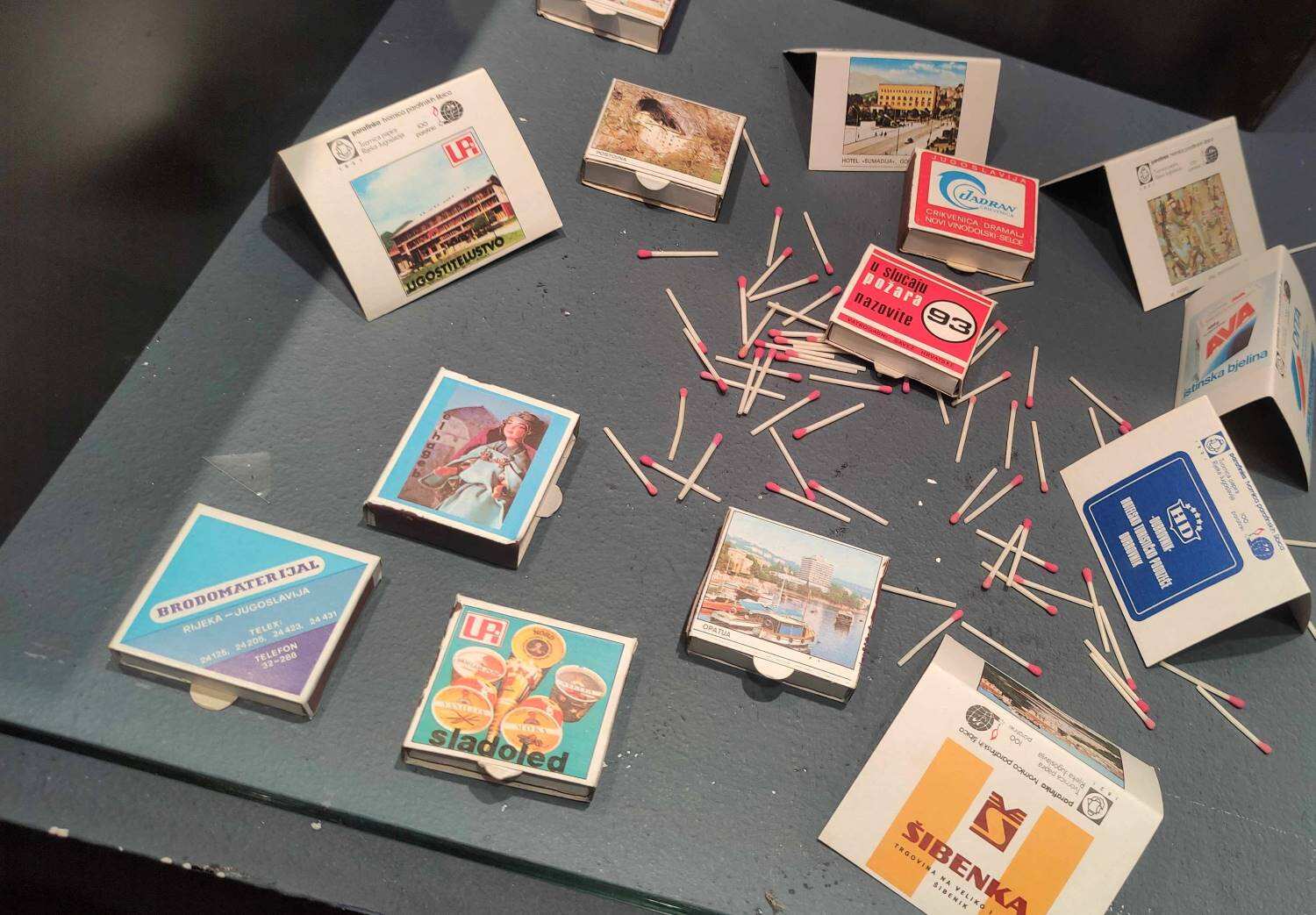

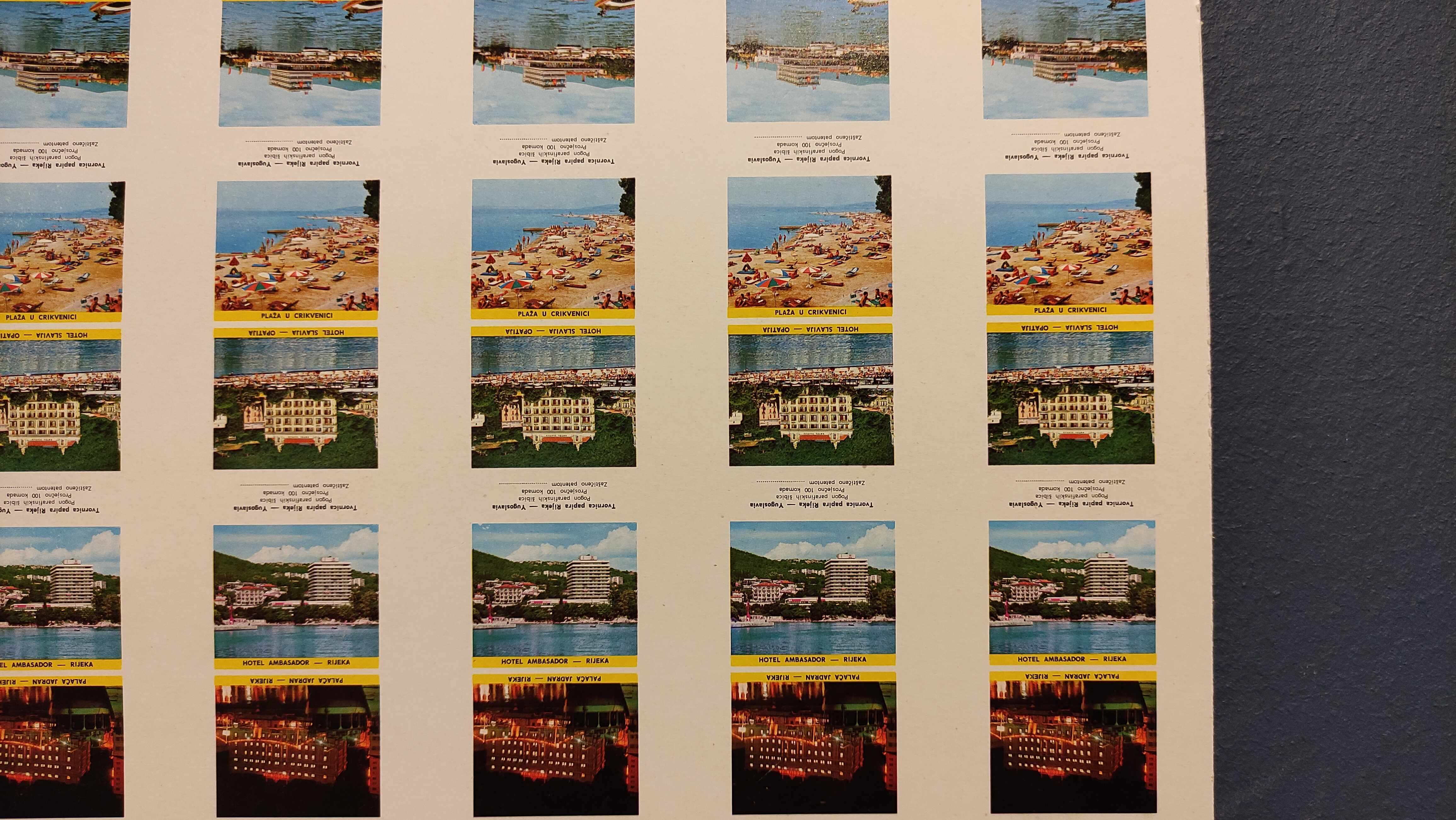

4 billion matches a year

In 1971, one part of the Hartera plant was repurposed into a match factory named Parafinka. It was the only paraffin match factory in former Yugoslavia and became immensely successful within a decade: a report from 1981 shows that Parafinka produced around 48 million matchboxes that year, each box containing 80 matches. That’s close to 4 billion matches! If the figure is hard to grasp, let’s put it this way: if you were to arrange all those matches in a single line, it would circle the Earth three times.

Matches were made of Hartera’s thin, tightly rolled paper and then dipped in paraffin, resulting in a product which was thinner and shorter than wooden matches. The packaging was quite attractive, with colourful prints announcing major events and manifestations, advertising businesses, or promoting the region’s natural beauty and cultural heritage.

Parafinka matches were exported worldwide, including Libya, Egypt, USSR, Hong Kong, Austria, Switzerland, Belgium and the Netherlands.

Crises, disasters and the final blow

In almost two centuries of operation, the paper mill faced economic crises, wars, and a few natural disasters. The river Rječina was the main source of power for the factory, but also a destructive force. One severe flood damaged the plant in 1852, and the entire mill had to close down for several months after another disastrous flood in 1898. Flooding wasn’t the only threat: various parts of the plant burned down on four occasions at the turn of the 20th century.

Hartera survived all the hardships and - save for a few hiccups - continued to thrive until the war. In 1991, the company was at the height of its power: it employed over a thousand people and was the second biggest paper manufacturer in Europe.

Rijeka Paper Mill bulletin from 1990 / Nova riječka enciklopedija - Fluminensia

Unfortunately, the war times and the economic turmoil that followed turned out to be the only hardship Hartera couldn’t survive. Substantial losses led to the factory closing down and the company declaring insolvency in 2005.

Uncertain future

After the paper mill ceased operating, the factory turned into a unique venue for a music festival. Named after the location, the Hartera Music Festival took place in the derelict factory halls until 2016, when the ruinous objects were declared unsafe and the festival moved to another location.

Hartera Music Festival in 2008. Source: Tim Ertl / Flickr

The Hartera festival was part of an initiative aiming to revitalize the area and preserve an important part of Rijeka’s industrial heritage. The City initially expressed interest, but the plans fell through due to lack of funding and a bureaucratic wall; the same happened a few years later after another initiative was devised to transform the Hartera complex into a socio-cultural centre which was supposed to breathe life - and business - into the largely abandoned area.

It remains to be seen if anything will come of the plans to revive the rundown factory. The outlook isn't hopeful, but one thing is certain: the Hartera paper factory and its workers are an integral piece of Rijeka's history and will always remain a part of the collective memory of its citizens.

The content of this article is largely based on the information displayed at the exhibition Hartera bez harte at the City Museum of Rijeka (author of the exhibition: Kristina Pandža). Unless noted otherwise, photos were taken by the author of the article.

Torpedo Discovered Near Opatija Given to Rijeka City Museum

A torpedo which has been lying on the Adriatic's seabed near Opatija since the Second World War finds a new home thanks to the efforts of its finder and the local police.

A few days ago, the Primorje-Gorski Kotar police received two reports of the discovery of explosives left behind from the Second World War, which were found in local forested areas and during a dive in the sea in the Cres archipelago.

These bombs were taken by local police officers from the explosion detachment division of the Primorje-Gorski Kotar Police Department and will be disposed of properly in strict accordance with the rules of the profession according to a report from Morski.

The police have extended their thanks to the conscientious people who found these explosives for the report and on this occasion have appealed to all other citizens not to touch any explosives they might come across, but instead to immediately call the police on the number 192.

The police also urge citizens who still hold unregistered weapons or explosive devices to voluntarily surrender them to the police as part of the implementation of the "Less weapons - less tragedy" campaign without fear of sanctions. Neither misdemeanor nor criminal proceedings will be instituted against persons who voluntarily surrender the said weapon(s) or any other explosive devices they have in their possession.

The police would also like to thank and ask citizens not to dispose of explosives or weapons anywhere, such as in forests, seas, lakes, rivers or landfills due to the risk of their activation. They also ask that people don't bring any of these dangerous items themselves to police stations, but to call the police in order for experts to come and safely remove any explosives. Following a call, police officers in civilian vehicles and clothing will come and deal with the items.

As Morski writes on the 22nd of October, 2019, Opatija police received a report Monday from a citizen who spotted a torpedo-like object in the sea in the wider Opatija area.

In addition to the staff of the Opatija police, others who are competent in assessing and handling such potentially delicate situations were also quickly dispatched to the scene.

The find was determined to be a torpedo air tank, albeit without a warhead, and there is thankfully no possibility of its unwanted activation. The torpedo was recovered and removed from the sea and transported to Rijeka, from which the torpedo draws its roots. It is being housed at the Rijeka City Museum, where it is likely to stay.

Make sure to follow our dedicated lifestyle page for more.