Making Science Sexy: Igor Rudan's Incredible Video Series: Survival, the Story of Global Health

March 31, 2020 - Eminent Croatian scientist Igor Rudan has written some of the most authoritative and clear texts on COVID-19. Now watch him explain Survival, the Story of Global Health. Science IS sexy.

I wrote an article a couple of days ago in which I said that I was not in the habit of writing an article praising people I had never met, which is true.

And yet, here I go again... Maybe it is the cabin fever starting to show.

Croatia has many heroes at the moment, from the dedicated health workers on the corona frontline to those in power with the huge responsibility to keep Croatia safe and navigate the most unpredictable waters that the world has known in my lifetime.

And these heroes and heroines are more than rising to the task, and I think them sincerely on behalf of me and my family (and, I suspect, the rest of the country). We have already written about new Health Minister Vii Beros and the legendica that is Almenka Markotic.

And so we come to our third hero of the hour, whom I have also never met. Indeed - please don't tell him, as I am a little embarrassed to admit it - I had no idea who he was until my colleague Lauren starting translating and publishing his amazing texts about corona on TCN.

(Just like Alemka and Vili, Igor Rudan also makes the list of the current top 10 most positive people in Croatia)

And when I read the articles on corona by Igor Rudan, I felt even more embarrassed. They were the most detailed, clear and factual articles I have read since this madness began. His latest answers one of the questions that maybe people are asking, but nobody seems to know the answer to - but Igor does.

Igor Rudan Explains What Went So Wrong With COVID-19 in Italy

You can read more of Lauren's translations of Igor's corona masterpieces here.

I decided to seek him out for a TCN interview and was surprised to find that we were friends on Facebook. I have currently 3,546 FB friends, and I know about 200 of them, but many Croatians seem to like to connect with a fat Irishman living in and writing about their country, which is great.

As we were friends on FB, that made the communication easier, so I sent him a link to one of Lauren's translations and said we would be happy to do more, so that his wisdom could go beyond the confines of the svjetski jezik, hrvatski, and into English.

Not only did Igor agree, but he was happy to add his superstar name to the TCN team of writers, thereby tripling the TCN IQ in one fell swoop, insisting that the texts appear in English first on TCN, and then he hired Lauren to translate lots of his other work.

It is a marriage made in heaven, and I have not seen young Simmonds as enthused about translating since we first met 4 years ago.

An extremely funny man from our messaging exchanges, he is the person I am most looking forward to meeting after all this madness is over (as well as holding Mate Rimac to his promise to let me drive him around in his $2.75 million C2 electric wonder car - I have promised to drive slower than Richard Hammond).

And then THIS!

My wonderful wife sent me a link to a YouTube video yesterday - Igor Rudan presenting Survival, the Story of Global Health.

It is sensational! Beautifully filmed, calmly and intelligently presented by Igor himself, mostly shot in Croatia, as well as Edinburgh, where he is a Prof at the university.

We called the kids to watch it together as a family. Watching their initial lack of enthusiasm turn to fascination during the first episode was a joy.

For those of you watching reruns of NCIS and Law and Order, THIS is for you. Check out the full series below.

And the final bit of reassuring news for this article. Igor messaged us last night to apologise for a short delay in sending us an article update. He explained that he had spent most of the day advising the Croatian authorities on the response to corona.

Doesn't it make you feel just a little safer knowing that those tasked with keeping us safe are taking advice from the very best?

Igor Rudan: Cascade of Causes That Led to COVID-19 Tragedy in Italy and Other EU Countries

March the 29th, 2020 - Professor Igor Rudan is the Director of the Centre for Global Health and the WHO Collaborating Centre at the University of Edinburgh, UK; he is Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Global Health; a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and one of the most highly cited scientists in the world; he has published more than 500 research papers, wrote 6 books and 3 popular science best-sellers, developed a documentary series "Survival: The Story of Global Health" and won numerous awards for his research and science communication.

The perception of the COVID-19 pandemic in my homeland Croatia has been based on two main sources of information over the past three weeks. On the one hand, our Civil Protection Headquarters, as well as all of the experts and scientists to whom media space has been provided, called for caution, but without any panic. They emphasised that this was not a cataclysm, but an epidemic involving a serious respiratory infectious disease. The cause of this disease is the new coronavirus, for which we don’t have a vaccine. Therefore, it can be expected that the disease will be very dangerous for the elderly and to those who are already ill. So, it was an unknown danger worthy of caution, but our epidemiologists remained calm. They knew that they would be able to estimate the epidemic's development using figures, and then control the situation with anti-epidemic measures, and through several lines of defense.

On the other hand, we also followed the events in Italy. From there, day after day, apocalyptic news came, with incredibly large numbers of infected and dead people. Daily reports from Italy seemed completely incompatible with what the experts and scientists in Croatia were saying. Some have concluded that a scenario similar to that in Italy, if not worse, is inevitable for Croatia. The population was in a very confusing situation.

In this text, I will try to penetrate the very core of the "infodemia" that has been present in the media across many European countries, as well as on social networks, over the past three weeks. I will explain how that disturbing situation arose and offer a scientific explanation for it. This seems important to me at this point, because the Italian tragedy with the COVID-19 epidemic has, unfortunately, hindered the credible and scientifically based communication of the epidemiological profession to the population of Croatia.

In my article "20 Key Questions and Answers on Coronavirus" posted on the 9th of March, 2020 on Index.hr, in answer to question number 18, "With the effectiveness of quarantine in China, can we draw some lessons from this pandemic?", I stated:

"If the virus continues to spread throughout 2020, it will demonstrate in a very cruel way how well the public health systems of individual countries are functioning… These will be very important lessons in preparation for a future pandemic, which could be even more dangerous.’’

We’re now slowly entering a phase where many countries have been exposed to the pandemic for long enough. Thanks to this, we can make some first estimates of their results. From these days up until the end of the pandemic, we’ll see that COVID-19 will divide the world into countries that have relied on epidemiology and followed the maths and the logic of the epidemic, as well as those in which this isn’t the case, and many sadly, probably quite unnecessarily - will suffer.

An epidemic is a serious threat to entire nations, during which residents' interest in other topics may vanish quite rapidly. We could see that happening quite clearly in the past several weeks. The task of epidemiologists is to constantly have tables in front of them with a large number of epidemic parameters, reliable field figures and formulas to monitor the epidemic's development, and to know the ‘’laws’’ of epidemics, in order to organise the implementation of anti-epidemic measures in a timely manner and thus protect the population.

Now, let's look at the countries that we can already point out as being successful in their response to this new challenge. First and foremost, there’s China. It has completely suppressed the huge epidemic in Wuhan, which spread to all thirty of its provinces. In doing so, it relied on the advice of its epidemiologic legend, 83-year-old Zhong Nanshan. Twenty years ago, Nanshan gained authority by suppressing SARS. Although surprised by the epidemic, they managed to suppress COVID-19 throughout China through expert and determined measures. They did so over just seven weeks, with the death toll eventually coming to a halt at less than 5,000. By comparison, it would be as if the number of deaths in Croatia as a result of this epidemic was kept at around 14 in total.

Furthermore, if at some point you find yourself caught up in the uncertainty surrounding the danger of COVID-19, you will easily be able to find out the truth if you look at the state of things in Singapore. Despite intensive exchanges of people and goods with China since the outbreak of the epidemic, Singapore has a total of 732 infected people as I am writing this article, with two dead and 17 more in intensive care. This city-state has the ambition to be the best in the world in all measurable parameters. From this, it must be concluded that the developments in Singapore are a likely reflection of the real danger of COVID-19. However, this is true of countries that base their regulation on knowledge, technology, good organisation and general responsibility. The situation in Singapore, therefore, is an indicator of the effects of the virus on the population, to the extent that it is truly unavoidable.

Any deviation towards something worse than the Singaporean results will be less and less of a consequence of the danger of the virus itself, and increasingly attributable to human omissions. In doing so, human errors that can lead to the unnecessary spread of the infection are: (1) the epidemiologists' omission to properly understand the epidemic parameters; (2) decision-makers' reluctance to make decisions based on the recommendations of epidemiologists; and (3) the irresponsible behaviour of the population in complying with government instructions.

To confirm the statements about Singapore, let's look at the current situation in other countries that rely on knowledge and expertise and have good organisation. They were also the most common destinations for the spread of the epidemic from China in the first wave: Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar. There were only 519 infected people in Hong Kong at the time of writing this article, with 4 deaths and 5 more people in a serious condition; in Japan 1,499 were infected, 49 were dead and 56 were in a serious condition; in South Korea, which had a severe epidemic behind its first line of defense, 9,478 were infected, 144 died and 59 were seriously ill; in the United Arab Emirates, 405 were infected, 2 died and 2 were seriously ill; and in Qatar, 562 were infected, 6 were seriously ill, and still no one had died from COVID-19.

Fortunately, Croatia is now up there with all of these countries, with 657 infected, 5 dead and 14 more seriously ill. As you can see pretty clearly from all of these figures, in countries that rely on knowledge and the profession and properly applied anti-epidemic measures, COVID-19 is a disease that should not endanger more than 1 percent of all infected people. This conclusion can be reached by considering that the information on the "https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus" page is based on positive tests, and not on everyone who is actually infected.

What, then, is happening in Italy, as well as in Spain, but to a good extent also in France, Switzerland, Belgium, Austria, Denmark and Portugal? I did not include Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States in this group of countries for now. This is because at least for some time during the epidemic, they have clung to the idea of intentionally letting the epidemic develop and infect at least part of the population, so I will refer to their strategies and their results in one of my following texts.

Given all of the previous examples of a successful epidemiological response, and what is now practically the coexistence of people with the new coronavirus in Asia's most developed countries, how is it possible for Italy to have nearly 85,000 infected people and over 9,000 deaths at the time of this article? How is it possible that Spain has 72,000 infected people and more than 5,600 deaths, and France has almost 33,000 infected people and 2,000 deaths? Or that even Switzerland, which everyone would expect to see among the most successful countries in any of these world rankings, could already have 13,250 infected people and 240 deaths, with 203 more critically ill people? The causes of all of this are, however, becoming increasingly clear to science.

First of all, there was probably a premature relaxation around the real danger of COVID-19 in Europe. The epidemic development by the end of February was already quite similar to the one seen previously with SARS and MERS. Even then, the primary focal point was suppressed, and in more than 25 countries, the virus was then stopped at the front lines of defense. By the end of February 2020, it was already clear in the case of COVID-19 that it would be successfully suppressed in its primary focal point - Wuhan. It was also already stopped at the front lines of defense in another thirty Chinese provinces and surrounding countries in Asia. Then, on February the 28th, the first estimates of death rates were published, saying that it was a disease with a death rate significantly lower than that of SARS and MERS. At that time, it was reasonable to expect that the epidemic could soon be

stopped. As a result, the World Health Organisation delayed the declaration of a pandemic until March the 11th, and the world stock markets increased by about 10 percent from February the 27th to March the 3rd. But for any unknown virus, premature relaxation is very dangerous, as will be shown later with COVID-19.

Secondly, several investigative journalists reported that it may be possible that the phenomenon of the mass immigration of Chinese workers to northern Italy may have contributed to the early introduction and spread of the virus in Europe. Tens of thousands of Chinese migrants work in the Italian textile industry, producing fashion items, leather bags and shoes with the brand "Made in Italy". Partly as a result of this development, direct flights between Wuhan and Italy were introduced. Some estimates say that Italy has allowed up to 100,000 Chinese workers, initially from Wenzhou, but later also likely from Wuhan and other cities neighbouring Shanghai, to work in those factories. Some of them may have been there illegally and worked in conditions where they were cramped together, which would help the virus to spread easily. Reporter D. T. Max wrote about this phenomenon in the New Yorker magazine back in April 2018. After their return from the Chinese New Year celebrations in mid-February, the Italian authorities rigorously checked these workers on their "first line of defense" at the airports. But rumours began spreading that some had begun to enter Italy but were bypassing Italian airports. Instead, they were going through other airports in the EU where controls weren’t as tight. So, the COVID-19 epidemic was likely triggered behind the back of the Italian "first line of defense", which remained unrecognised in the first few weeks.

Third, many infected people from northern Italy spent their weekends at European ski resorts. Although we don’t know if the arrival of the warmer weather will stop the transmission of coronavirus, what we can assume is that the cold helped it to spread. That is why European ski resorts became real nurseries of coronavirus in late February and in early March. In this way, more infected people emerged behind the front lines of defense in France, Switzerland, Belgium, Austria, Denmark, Spain and Portugal. Their first lines of epidemiological defense focused on air transport from Asia, not on their own skiing ‘’returnees’’, where indeed no one would expect a large number of Chinese people from Wuhan to be.

Fourth, although Spain may not have had as many skiers as other European countries in this cluster, the virus may have been introduced to them through a "biological bomb". On February 19th, a Champions League football match was held between Atalanta and Valencia. Atalanta is a team from a small city of Bergamo, Italy, which has 120,000 inhabitants. This was possibly the biggest game in Atalanta's history, as it progressed through group stages to the last 16 in the European Champions League. The local stadium was not large enough for everyone who wanted to attend the game, so it was moved to a large San Siro stadium in Milan.

The official attendance was 45,792, meaning that a third of Bergamo’s population, with around 30 busses, travelled from Bergamo to Milan and then wandered the streets of Milan before the game. Unfortunately for Spain, nearly 2,500 Valencia fans also traveled to the match. As Atalanta scored four goals, a third of Bergamo's population was hugging and kissing in the cold weather four times and spent the day closely together. This is likely why it became the worst-hit region of Italy by some distance. Unfortunately, at least a third of the Valencia football squad also got infected with a virus and later played Alaves in the Spanish league, where more players of that team got infected. This football game has certainly contributed to the virus making its way to Spain.

Fifth, it’s very important for the early development of the epidemiological situation in each country to look at which subset of the population the virus has spread among. Northern Italy has a very large number of very old people. In the early stages of the epidemic, the virus began to spread in hospitals and retirement homes. They didn’t have nearly enough capacities to assist in the severe cases. Among already sick, elderly and immunocompromised people, the virus spread more easily and faster and had a significantly higher death rate. In some other countries, such as Germany, most of the patients in the early stages were between the ages of 20 and 50, and were returning from skiing trips or were business people. Therefore, such countries have a significantly lower death rate among those first infected.

Sixth, and what the most important thing needed to understand the current situation in Italy is, must have been either the omission of Italian epidemiologists to monitor the mathematical parameters of the epidemic, or perhaps their lack of clear communication of the dangers to those in power in northern Italy, or the indecisiveness of those in power to adopt isolation measures for the population. It is difficult at this time to know which of these three causes is the most important, and a combination of all of them is entirely possible. However, I will explain the nature of the omission, as it largely explains the terrible figures on infections and deaths that are being reported from Italy on a daily basis.

To understand the story of this tragedy in Italy, we must first return to Wuhan. When the epidemic broke out, the Chinese first had to isolate the virus. Then, they needed to read its genetic code and develop a diagnostic test. It all took time, as the epidemic spread rapidly throughout the city. When they began testing for coronavirus, between January the 18th and the 20th, they had double-digit numbers of infected people. Those numbers apparently stagnated, so the epidemiologists didn't know what that might mean. But on the 21st of January, the number of newly infected people jumped to more than 100. On the 22nd of January, it jumped to more than 200. This was a clear signal to Chinese epidemiologists that an exponential increase in the number of infected people was occurring. At that time, they had nothing further to wait for, or to think about. If the virus breaks through the first line of defense - and the Chinese didn’t even have any, since the epidemic started there - then a quarantine measure needs to be triggered. This prevents the virus from spreading further and creating a large number of infected people through exponential growth.

After such a sudden declaration of quarantine in Wuhan, the huge epidemic wave of the Chinese had actually just begun to show. Everyone who was already infected began to develop the disease in the next few days. The maximum daily number of new infected cases was reached on the 5th of February. On that day alone, as many as 3,750 new patients were registered in Wuhan. Remember, this means that the jump from about 125 to about 250 registered newly infected people signals to epidemiologists that we should expect an epidemic surge in 14 days, with as many as 3,750 newly infected people in one single day.

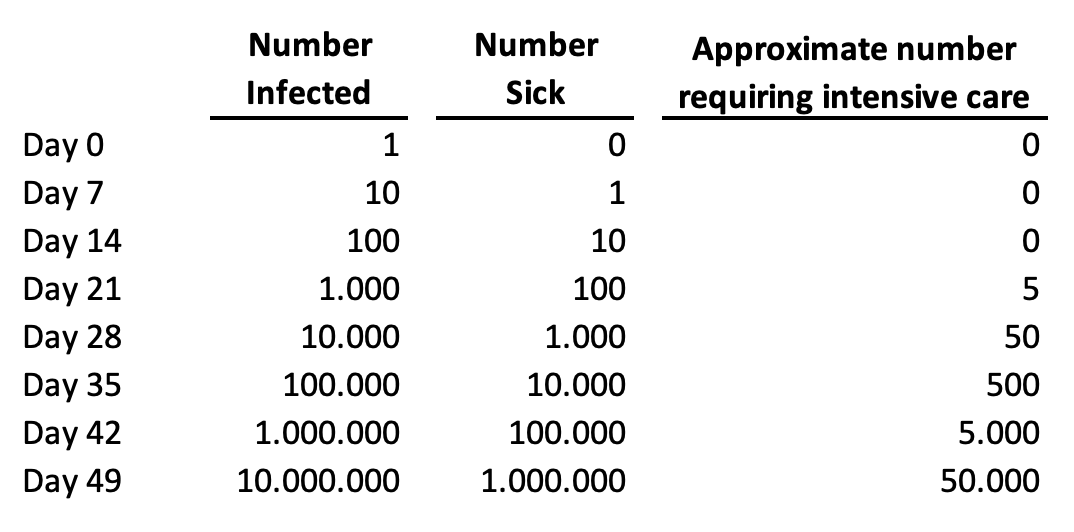

Let's now explain this "time delay" between people getting infected with the virus and the health system being able to detect all those infected people based on their symptoms. The new coronavirus kills primarily because it spreads incredibly quickly among humans. As a result, it creates a gigantic number of infected and sick people in a very short time period. Among those who are sick, about 5 percent will require hospital care. If all of them could receive optimal care, we'd be able to save nearly everyone. But if they all get very sick at the same time, we can't offer them adequate care and nearly all of the critical cases will die. This is the primary way in which this virus kills so many people. It is illustrated in a very simple way in this table, based on day-to-day growth in a number of cases by 26 percent, which was a very realistic scenario for most EU countries:

TABLE ONE: The dynamics of the epidemics of COVID-19 in any given country, based on a realistic scenario of about 26 percent of day-to-day growth of the number of cases:

With this in mind, let's now look at the Italian reaction to their own epidemic. In the early stages of infection spreading in a country, one or two infected persons are usually detected daily. Personally, I advised the Croatian authorities and public to start seriously thinking about social exclusion measures when they noticed the first notable shift from the first 10 confirmed infections towards the first 20 infected people.

On March the 12th, I posted a Facebook status entitled "Contrast is the mother of clarity", which was viewed and shared by many thousands of my fellow Croatians who have been following my popular science series on the pandemic - "The Quarantine of Wuhan". This status has also been shared by many online and printed newspapers and media, including radio stations. In that status, I suggested that Croatia should consider a large quarantine because we had already jumped from 14 to 19 infected people the day before, but to also weigh this against the economic implications and their expected effect on health. The very next day, a decision was made to close the schools.

That meant that, up to that point, Croatia completed two of the most important tasks in this pandemic. The first task was to hold its first line of defense. This was being achieved through the identification of infected cases imported from other countries and their isolation, and that of all of their contacts. Croatia completed this first task better than the other EU countries did, based on an average percentage increase of cases between the 3rd of March and the 17th of March. Then, from March the 13th, Croatia also began to introduce social exclusion measures at the right time, thus successfully carrying out the second key task in controlling its own epidemic. Many credits go to its epidemiologists who work at the Croatian Institute for Public Health.

But, what went wrong with these two measures in Italy? On the 21st of February, their number of confirmed infected cases jumped from 3 to 20. As Italy is a more populous country than Croatia, it might have still been too hasty to send all of Lombardy into quarantine based on this. But on the 22nd of February, the jump was from 20 to 62 cases, and they already needed to think very seriously about it. A couple of days later, on the 24th of February, they reached a situation very similar to that in Wuhan as the number of confirmed infections jumped from 155 to 229. This was particularly worrying because they didn't seem to be performing many tests proactively at that time, either.

That "jump" from 155 to 229, in combination with the Wuhan experience, should have suggested that they would have at least 50,000 infected people under the predicted curve of the epidemic wave and they were just seeing its early beginning. And that many infected people would mean that about 2,500 affected would require intensive care units. At the time, Lombardy had only about 500 such units in government/state facilities and another 150 in private healthcare facilities. As early as 24th of February it was clear that there would be many deaths in Lombardy weeks later. With epidemics, everything goes awry because the infected get sick a week later, and some of the patients then die ten to twenty days later, so the time delay is always an important factor that needs to be taken into account.

However, even then, the Italians didn’t declare a quarantine. They didn’t do so on the 29th of February, either, when the total number of infected people rose from 888 to 1128. Those figures implied that in mere days they would be having about 15,000 newly infected people each day. Moreover, they didn’t declare quarantine on the 4th of March, either, when the number of infected people exceeded 3,000, and when the world stock exchanges started to fall again. It had then become clear to most epidemiologists who have been advising global investors that an unexpected and major tragedy was about to unravel in Italy and this was now inevitable. At that point, Italy already had at least 30,000 infected people spreading the infection. The quarantine was declared for Lombardy on the 8th of March. The day before, the number of cases had already risen, and exponentially so, to as many as 5,883.

To appreciate the problem with epidemic spread in the population behind the first line of defense, this is similar to borrowing 1,000 Euros from someone on the 29th of February with an interest rate of 26% each day, meaning an interest rate of 26% on top of that the next day, and so on. Furthermore, there didn’t seem to be enough clear and decisive communication with the public. The news of the quarantine for Lombardy was, in fact, leaked to the media before it was officially announced. This led to a quick ‘’escape’’ of many students to the south of the country, to their homes, carrying the contagion with them. As a result, a day later all of Italy had to be quarantined.

In an already difficult situation, where every new day of delay meant another thousand or more people dying, as we can all notice these days, there were numerous media reports warning that the population may not have taken those measures as seriously as the Chinese when they introduced orders to their population in Wuhan. Any indiscipline under such grave circumstances could have allowed the virus to take yet another step quite easily. With each new step, another 26% of interest was added to everything before that, and then 26% on everything on everything before that again. That is the power of exponential growth, characteristic of free spread of the virus in the population.

Many Italians and then Spaniards, as well as residents of several other wealthy countries in Europe, had their lives cut short by their lack of recognition of the dangers of exponential function during the spread of the epidemic. Delaying quarantine for a week made the epidemic ten times worse than it should have been. Delaying it for two weeks made it a hundred times worse. And after two weeks of it being finally proclaimed, all those who may have not taken the orders seriously enough would have made the epidemic several hundred times worse. This means that, in Italy, and possibly in Spain, too, we are now observing the COVID-19 epidemic that is more than a hundred times worse than it should have been in a country that was much better prepared for the response, such as Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong or the United Arab Emirates.

To appreciate what is happening in Italy, it is enough to think of this sentence alone: at least 100 times fewer people would die each day if quarantine had been declared 2 weeks earlier and had the population stuck to the recommendations. During those fourteen days between 23rd of February and 7th of March, they unnecessarily allowed the virus to spread freely and infect a huge number of people - maybe even up to a million, or perhaps more, it is very difficult to know at this point. This would mean tens of thousands of people in need of intensive care, with about ten times fewer units available nationwide. About half of those who fall seriously ill will not survive without necessary support. At this point, whenever we hear that 1,000 people died in Italy in one day, we should know that the casualties would only add up to 10 had the quarantine been declared just a couple of weeks earlier. I appreciate that it seems implausible that the delay of a political decision like the introduction of quarantine by just two weeks may mean the difference between 100 deaths and 10,000 deaths in the 21st century, but I’m afraid that is unfortunately the reality of the exponential growth of the number of infected during an epidemic.

What does this mean for the public in countries like Croatia, who were confused and in awe of the events in Italy? They should know that they didn’t observe what the COVID-19 epidemic should actually look like in a country where the epidemiological service and its communication with those in power works well, as it does in Singapore, Taiwan or South Korea. In Italy, we have unfortunately noticed the consequence of an omission of epidemiologists and those in power to protect the people from the epidemic. Such a development was not predictable at all. The biggest surprise of this pandemic to date is undoubtedly the lack of response by the Italian authorities to the apparent spread of the pandemic at an exponential rate for two weeks, leading to a very large numbers of infected people in a very short time. But, it is even more surprising that, although the Italian example exposed the lack of capacity of their healthcare system to provide care to all those in need, a similar scenario is now happening in several other European countries in this group, that I initially singled out.

How and why could something like this happen in Italy and then in other countries in the European Union (EU)? I will try to offer at least some hypotheses. First, EU countries have been living in prosperity for decades, focused mainly on their economies. Aside from the economic questions, they haven’t had any challenges that they’ve had to answer to swiftly and decisively, that would measure up to this one. Back in the 1960s, vaccines were introduced against most major infectious diseases, especially childhood ones. Malaria is no longer present in Europe and tuberculosis has been treated similarly for decades. The challenge of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s is now being successfully controlled with antiretroviral drugs. Liver inflammation is treated mainly by clinicians. The impact of influenza is controlled through vaccination while rare zoonoses are resolved with immunoprophylaxis. Even sexually transmitted infectious diseases (STDs) are no longer as significant since the vaccine for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) was licensed.

The last real epidemic that concerned Europe was the Hong Kong flu, which occurred back in 1968 and 1969. The broad field of biomedicine offers such a wide range of exciting career paths to all those students who study it these days, but the epidemiology of infectious diseases is certainly not one of them, at least it has not been in Europe for a very long time. It has probably begun to seem as an archaic medical profession to the large majority of students and young medical doctors. It seemed to belong to the past for the European continent, which made it one of the least attractive things to specialize in. Even the rare epidemiologists who specialized in infectious diseases have begun retraining for chronic non-communicable diseases, due to the aging of Europe's population, which is particularly the case in Italy and Spain. It seems that at least some EU countries may have fallen victims to their own, decades-long success in the fight against infectious diseases. They faced this unexpected pandemics with few experts that could have had any experience in these events. Asian countries, as well as Canada, have had enough recent experience with SARS and MERS, but some European countries seem to have forgotten how to fight infectious diseases. If it were not for the legacy of the great Croatian epidemiologist and social medicine expert and global public health pioneer Andrija Štampar, and the relatively recent war in Croatia, it is difficult to say whether or not Croatia would be as ready as it has proven to be.

Another thing that likely undermined the Italians response was that no one before Italy, in fact, could have seen how fast COVID-19 was spreading freely among the population. The absolute greatest danger of COVID-19 is its accelerated, exponential spread when it breaks through the first line of defense. However, no-one had the opportunity to study this thoroughly before it reached Italy. Previously, only the Chinese in Wuhan and the Iranians had experienced the free spread of the infection. After five days of monitoring the number of infected, the Chinese had to quarantine Wuhan, and further 15 cities a day later, in order to contain the virus. They did not know how many infected people were outside of their hospitals. For Iran, however, no one knew exactly what was happening there, as that country is significantly isolated internationally due to political reasons. The Koreans, however, had a limited local epidemic but not an uncontrolled free spread - they caught the virus using their first line of defense.

That’s how the Italians ended up becoming the first country in the highly developed world to monitor their epidemic spreading uncontrollably among the population. The only estimate of the rate of spread of the virus to date has been in the scientific work of Qun Li et al. from the 29th of January, published in the New England Journal of Medicine. However, it was difficult for them to subsequently determine R0 parameter on the first 425 patients in Wuhan. Their estimate of the R0 for COVID-19 was 2.2, but with a very wide confidence interval - from 1.4 to 3.9. It's a bit of tough luck again that they calculated the lower bound of the confidence interval to be 1.4 exactly, because this figure is well known to all epidemiologists. It's the rate of the spread of seasonal flu in the community. It should come as no surprise that many epidemiologists would guess that, with more data, R0 for COVID-19 would start converging more towards 1.4. Unfortunately, the more recent data suggests that R0 is more likely to lean towards 3.9, implying an incredibly fast spread. Thus, the greatest danger of COVID-19 remained unrecognised in Italy until the 8th of March quarantine measures. At least 100 times fewer people would be dying in Italy these days had they declared a quarantine for Lombardy two weeks earlier than they did.

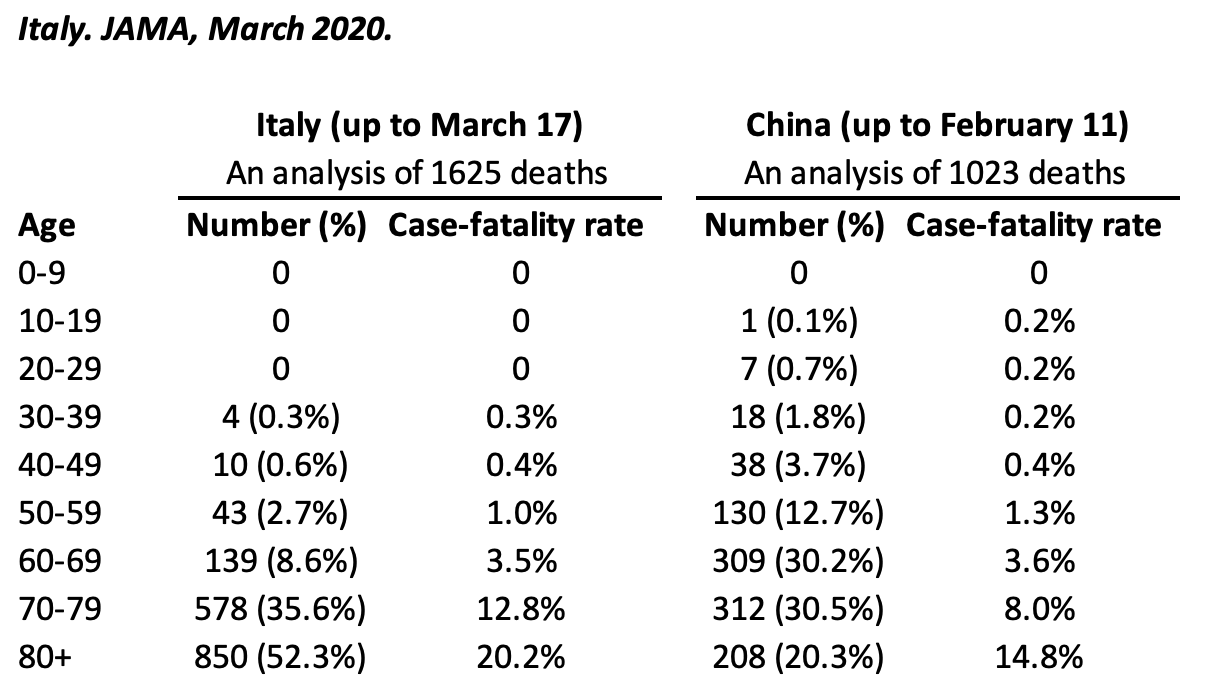

Just a few days ago, the JAMA journal published another extremely useful piece of scholarly work, authored by Odner et al. Their contribution finally provided answers to three great unknowns about COVID-19. Many myths about the situation in Italy have been present in the media since the very outbreak of the epidemic, but thanks to just one simple table, today we can finally dispel them all.

The first is the question that has plagued us all for a long time - how dangerous is COVID-19 for younger age groups? It is clear that the media will tend to single out individual cases of death in younger people, as they are of most public interest. However, it’s interesting that until recently, we didn’t have decent data on this. The first reason was that the Chinese Centre for Disease Control reported all deaths in Chinese epidemic using age group structure that contained a very large age group of "30-79 years". It only separated children up to 10 years, then adolescents up to 20 years, then 20-29 year-olds, then this huge group, and then those who were 80 years of age or older. That’s why the work of Odner and colleagues is commendable, as they made an effort to divide this large group into 10-year age groups. This finally allowed a comparison between the first 1,023 deaths in Wuhan (up to the 11th of February) with the first 1,625 deaths in Italy (up to the 17th of March). The comparison is shown in the Table 2 below. It gives us some very important insights.

Firstly, in Italy, more than half of the deaths initially were among people who were older than 80 years of age, and a total of 88% of the deaths occurred among the persons over 70 years of age. So, contrary to the impression that individual media reports can easily make, COVID-19 is a very dangerous disease mainly for the old people. Moreover, a study by A. and G. Remuzzi in the March 2020 issue of Lancet showed that, among 827 deaths in Italy, the vast majority of those people were already severely ill with underlying diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and malignancies. This is what epidemiologists expected, because a more severe flu would have had a similar effect if there was no vaccine available. However, I doubt that the general public have the proper insight into this issue from many media reports.

Secondly, it was suggested in the media across Europe that the virus in Italy may have mutated and become much more dangerous. However, Table 2 shows that death rates by the age of 70 are practically the same in China and Italy. Then, although the case fatality rate appears to be about 50% greater in Italy than in China for the age group 70-79, this does not suggest that the virus may have mutated. It is known that in Wuhan, many of the affected with a severe clinical presentation of COVID-19 could rely on the two newly built hospitals and respiratory aids that the military had brought in from other parts of China. They also had medical teams coming in from other provinces. In Italy, however, there were not enough respirators for this age group, and there weren’t enough doctors either, as many of them themselves became infected. For those two reasons I would, in fact, expect even a larger difference between Italy and China than the one we’re seeing, so I would not attribute this observed difference to the impact of the virus itself. And finally, the reported difference in case-fatality rates for the oldest age group should also not be attributed to the virus. It is more likely a consequence of the fact that Italians of Lombardy live, on average, longer than the Chinese of Wuhan. Therefore, there are significantly more people in the oldest age group in Italy, ranging to much higher ages, so the two oldest groups are not really comparable. The average age of the Italians in the age group "80 years or older" is significantly greater than the average age of the oldest Chinese age group. Therefore, the table shows practically equal death rates across all age groups, on sufficiently large samples, meaning that the virus didn’t mutate in Italy from the virus we see from Wuhan, at least not until the 17th of March, 2020.

TABLE TWO: Adapted from: Graziano Onder et al. COVID-19 Case-Fatality Rate and Characteristics of Patients Dying in Italy. JAMA, March 2020.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly - this chart has now made it quite clear that COVID-19 does not, in fact, kill people under the age of 50 unless they have some sort of underlying disease, or some unknown "Achilles heel" in their immune system that makes them particularly susceptible to the virus. There are such cases with every infectious disease. They are also present during the flu epidemics, but they are extremely rare. This suddenly gives us another possible quarantine strategy, where children and those under 50 years of age could first emerge if they don’t have any underlying illnesses. Here, after this table, it already seems like we are beginning to have an increasing number of options to get out of quarantines and learn to live with this virus until the vaccine becomes available. However, at least a few more studies need to be carried out to confirm that this age group can be substantially protected, to provide reassurance that the virus is not becoming more dangerous for those younger than 50 years old, too.

There is another strangeness to the situation in Italy that will not be intuitive to the general public. The actual number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 in Italy will not be possible to estimate for several months after the epidemic finally ends. Namely, at present, due to the sole focus on the epidemic, all of the cases of death of very old people who have been diagnosed using a throat swab have been attributed to COVID-19. However, once the epidemic is over, it will be necessary to compare the deaths in individual areas of Italy with the average for the same months in the previous few years. It could be shown that a part of the already ill would have died in the same month or year even without being infected with the new coronavirus, and that COVID-19 accelerated this inevitability by a few weeks or months. In this case, the so-called "reclassification" of causes of death will need to be carried out. The deaths observed during the epidemic in Italy will be attributed to underlying diseases in accordance with expected levels, and only those above expected levels will be attributed to COVID-19. This could ultimately reduce the number of Italians who actually died of coronavirus and otherwise would not have passed away that year.

This article provides an explanation from the epidemiologist's point of view for everything that has happened so far in Italy, and then followed in Spain and other European countries where COVID-19 has expanded through ski resorts and football games. Simply, a combination of an early relaxation, a possible inexperience in the management of infectious diseases, a systemic lack of expertise in the field, a possible evasion of immigration regulations, and a series of further misfortunes and human omissions have all led to the late withdrawal of Lombardy into quarantine. This allowed for a large number of people to be infected and severe illnesses led to death due to respiratory failure. In 88% of cases, people over 70 years of age died, who, in the vast majority of cases, had underlying illnesses already. But this is an analysis based on the first 1,625 deaths in Italy, and by the time of this writing, there are now more than 10,000 dead. Given the size of the population, this would correspond to 670 deceased in Croatia, which means that in Italy it is more than 100 times worse than it is in our country. This difference may be attributable almost entirely to a two-week quarantine delay.

These days, the people of Italy, Spain and other European countries are suffering large losses because of the problem that the human brain simply cannot intuitively grasp the power of exponential growth, nor that two weeks of delay could make the difference between 100 and 10,000 deaths. Any physics enthusiasts will know that the great Albert Einstein once warned us about this - he said that interest rates, which lead to exponential growth, are "arguably the most powerful force in the universe," to which no black hole is equal.

This text was written by Igor Rudan and translated by Lauren Simmonds

For rolling information and updates in English on coronavirus in Croatia, as well as other lengthy articles written by Croatian epidemiologist Igor Rudan, follow our dedicated section.

Igor Rudan: How Can We Move from Defence to Attack in Coronavirus Fight?

Why does the director of the World Health Organisation keep repeating: "test, test, test"? How are the conditions for quarantine created, how might coexistence with coronavirus look, and how can the virus be attacked?

As Igor Rudan/Vecernji list writes on the 26th of March, 2020, Croatia has become a major quarantine - temporarily. This prevents the new coronavirus from spreading too quickly. As a result, the number of serious COVID-19 cases in our country shouldn’t increase too rapidly. This will enable our healthcare system to help anyone who develops a more severe form of the illness. Our healthcare professionals will save many lives in the coming weeks. If we all adhere to the quarantine provisions, our health care system will continue to be able to help those with other illnesses in need of intensive care. By staying in our own homes, we’re all now protecting our health care system from overloading, which could otherwise occur under the pressure of too many coronavirus patients.

After all of us found ourselves in such an unusual situation, many people have been asking me questions over recent days. The most common of these are: "What will happen next?"; "How long will this last?"; "Why didn't we test a lot more and avoid quarantine, like some Asian countries did?" Many people are also wondering if we really have to threaten the economy this way in order to, as they say, "extend the lives of those among us who are already the oldest and the most unwell?"

It isn’t even clear to many why societies have created a climate that stops people's "right to die from COVID-19"? By comparison, about eight million people worldwide die directly from smoking annually. Nearly one million of those deaths are of non-smokers, who smoke their household members’ cigarette smoke. Why aren't the deaths of all these hapless "passive smokers" tracked in the same way? Furthermore, more than one million people die each year in road accidents. All drivers are exposed to it, but not everyone survives it, nor are they always guilty of it. Why is exposure to coronavirus different from driving exposure? Finally, about one million people die of AIDS a year. However, even with the total of ten million deaths per year, nobody is stopping people from smoking, driving cars, or having sex among their population. And now, because of COVID-19, we're all in our houses at once. We are also at risk from viruses and economic catastrophe, and obviously from earthquakes.

What’s going on here, then? Why are half a million people who end up dead from the flu every year completely uninteresting to the general public, but any deaths from COVID-19 are interesting to the point that country after country in the developed west sees this as economic suicide? Or, why aren’t the six million deaths of poor children worldwide interesting to the public? It seems that it would be even more reasonable to save the victims of all the aforementioned diseases than the predominantly retired, elderly and sick people around the world who are now at risk of being infected with COVID-19.

These are not simple questions at all and I'm not sure I have clear answers to them. I’m pleased, however, that the first clear plans, scientifically based ones, are finally coming out, on how to get out of this situation relatively quickly with minimal human casualties and avoiding the complete collapse of the economy.

The first step of all these plans is always to quickly and decisively close the pathways of further spread off to the virus. This avoids creating the situation of having too many infected people too quickly. The health system is then protected from complete collapse and many human lives will be saved. After that, there is a very wide range of further options. The author Tomas Pueyo recently outlined the currently most sensible coronavirus strategy and called it "The Hammer and the Dance." I expect that over the next few weeks, the governments of many developed countries will resort to some variant of this solution, because it’s reasonable. It protects people's lives and it protects the health system, but it also protects the economy. The ‘’hammer’’ is an intensive and not too long of a quarantine that reverses the flow of the epidemic and reduces the number of infected people. The ‘’dance" is then our coexistence with the virus, much like the escalation of Muhammad Ali-style strikes, where we must never again allow it to spread quickly to a large number of people.

Therefore, once this unusual situation is over, the assessment of each country's performance in dealing with the coronavirus crisis will be based on the following five questions:

1. How long and effectively did the "first line of defense" manage to prevent the free spread of coronavirus among the population? In the case of Croatia, we were practically the best in Europe.

2. When the virus broke through the "first line of defense" and began to expand exponentially throughout the population, how quickly and decisively was a strict quarantine measure activated? In the case of Croatia, the activation measures started at the right time, with the plan being not to have the number of infected people reach more than a few thousand and for the number of serious cases to reach only a few hundred. Were it not for the earthquakes and the fleeing of many from Zagreb down to the south, these figures would probably have been reached, but we’ll see in a few days just where the number of infected people will peak.

3. How closely did the population adhere to quarantine? We’re now dependent on the discipline of all of us, so that the problems that the Italians and the Spaniards now have because of their indiscipline don’t happen to us. So stay, if you can, inside your houses.

4. How fast and active was the state in mobilising its capacities and human resources, as well as creative and innovative solutions, to develop a concrete plan for quarantining and coexistence with coronavirus as quickly as possible? This is the next urgent task for Croatia. This will include the empowerment of technological capabilities and human resources for virus testing, innovative ideas on social removal measures, effective virus control measures, the use of technologies to understand human contacts and the spread of viruses, and other things.

5. How effectively, after quarantine, has the state allowed its inhabitants to move into a relatively normal life situation and preserve their economy from collapse, with permanent control over the spread of the virus? This is our fifth task, but it isn’t one that is unsolvable either.

How are we going to achieve this over the next month, and how can we continue after that? I will try to explain this with this simple story, which will explain our current situation to you, and the options at our disposal.

Let's first imagine the whole of Croatia as a group of one hundred people. Working on their computers, the group works a night shift at an office on the ground floor near Maksimir forest.

You can enter this ground floor through a rather long corridor. In Maksimir forest, as we know, there is a zoo. It is also said that a vampire wanders through the forest at night. Due to the proximity of wild animals and these rumours of a vampire, these one hundred office employees created a round ‘’net’’ made of very tough rope. They also tied one hundred bricks around the round edge of that net.

One night, a tiger escaped from the zoo. We heard about it on the radio and hoped it wouldn't come right to us, but we still pulled that net out of the closet. A moment later, the tiger walked right into our office. We threw the net at it and then each one of us firmly gripped those bricks on its edge and pressed the net down against the floor. As strong as it was, the tiger was now pressed down by the net thanks to the joint action of all of us one hundred people.

The tiger can't really do us any harm as long as each of us presses their own brick firmly against the floor. This is our current situation with coronavirus, this is quarantine.

However, all the tiger wants to do is take away just one of us and eat that person somewhere in the woods. He would leave everyone else alone and return again in a year. The oldest and most unwell people sit next to the hallway door, so the tiger would probably drag one of them away. To protect one of us, all one hundred must now hold their respective bricks pressed against the floor. It is not only tiring but it’s also boring. Nobody wants to live like that. But what else could we do? Some begin to slowly look at the old men among us, wondering if they’re really worth so much to us. Does it make sense to sacrifice the quality of life for ninety-nine of us just to save one of our old men? It is amazing that this virus has placed this type of doubt in front of us in the 21st century. Our response to the crisis will, in fact, reflect the value system of our society.

Still, everyone wondered how long we should keep this tiger pressed under the net and how to get out of this situation. Someone then remembered that vampire. If the tiger was accidentally bitten by the vampire on the way to the ground floor, then at sunrise, the tiger could simply disappear when it was illuminated by the sun. This is analogous to the disappearance of coronavirus when the warmer weather arrives. So, it seemed reasonable to endure it for at least some more time. Then one of us asked the person next to them to press down their brick with their free hand, while they try to load their rifle, with which they could simply kill the tiger. That would be an analogy for the discovery of a vaccine for this virus. Another, however, also freed himself and began to develop a fluid that would kill any appetite the tiger had. Then the tiger would leave us all alone and just walk away outside. This would be an analogy for the COVID-19 drug, which would reduce the need for respirators for the seriously ill and relieve the pressure on the health system.

Suddenly, there seemed to be as many as three options - the disappearance of the tiger at sunrise, the loading of a rifle, or the development of a fluid that would kill the tiger's appetite. The problem is, there can be no certainty that any of those measures would work. During this time, the people are less and less attached to the net. If only two or three loosen their grip in the same place, the tiger will crawl out from there, and then it would once again need to be caught in the net. However, more and more people, eager for a normal life, are beginning to wonder whether it’s better to gamble with the 99 percent chance that the tiger will not grab them than to live like this, crouching down on the floor and pressing the net against the floor with everyone else. This is especially the case for younger, faster and more adept people.

But suddenly, an engineer comes up with something else. He teams up with the miner next to him. They ask those next to them to hold down their bricks with their free hands, and they go out into the hall. The engineer instructs the miner to dig a tunnel under the corridor, which would lead back into the forest. During this time, he places ten tiles instead of the hall floor, each of them with a sensor. He installs a laser beam on the ceiling, which alternately illuminates one of these tiles. If the beam is directed at the tile sensor and the sensor doesn’t register the beam, it means that there is probably a tiger sneaking onto those tiles. Then the tiles will collapse and the tiger will fall down into the tunnel, and will have to go back into the woods and he’ll need to sneak up on us again from scratch. If the tiger ever manages to get through such a security system, we still have a rope with a bell at the end of the hall. It will alert us to the fact that he has broken through that defense and then we will catch it once again in the net. But in the meantime, we will at least be able to live more normally and continue to do our work, regardless of the fact that there is a tiger outside our building. When the system is installed and tested, we will push the tiger out together with our net, then allow it to keep falling through the floor tiles, let it fall into the tunnel again, and then return to the forest. That's how coronavirus testing works, roughly.

There is only one thing to remember in any epidemic: we need to do everything we can to find out who is infected and who isn’t, and then physically separate the infected people from the healthy ones. This should be done among the population, but especially in hospitals, where the virus poses the most danger if it can enter them. Since coronavirus has entered several of our hospitals, anyone considering the complete relocation of all COVID-19 infected people from all hospitals to reception centres, to new hospitals, which is what was done in Wuhan, has my full support. Every action of separating the infected from the rest of the population makes it impossible for the virus to spread further. The most important thing is to prevent it from spreading to uninfected hospital patients who are most at risk.

If we can be that active in finding infected people and isolating them and their contacts, we will significantly slow down the spread of the virus. This virus is currently spreading at a tremendous pace as each infected human can transmit it to two, three or even four healthy people with their next step. But if, by taking an active approach to finding infected COVID-19 spreaders who don’t yet have symptoms, and by constantly separating them and all of their contacts and putting them into self-isolation, then we manage to get to a situation in which one infected person manages to infect, on average, less than one healthy person, then we are all pretty safe. The epidemic will slowly go away on its own, and the vast majority of us will be able to live relatively normally. The minority, on the other hand, will constantly rotate in isolation.

With proactive testing, for example, by small epidemiology teams that will go to the households of everyone who reports having symptoms and test them and then isolate them and their contacts if they’re positive for the virus, we will allow the vast majority of the population to live safely with the virus. I would definitely recommend the daily testing of all staff at hospitals, dispensaries, health centres, as well as people employed in retirement homes, as there will also be an enormous amount of damage if a COVID-19 epidemic develops in those places.

In addition to actively seeking out, testing, and then isolating infected people and their contacts, there are two other elegant ways by which we can further protect ourselves. The first is to build some kind of "safety net". We could define a very representative sample of Croatia's population of about 10,000 people, and test them once a week. In this way, we would make sure that the virus isn’t "sneaking" behind our backs and escaping into exponential growth in some part of Croatia.

Namely, when we quarantine, it will be possible for mini-epidemics to break out anywhere in Croatia. They, as we’ve seen in Italy and some other European countries, can grow very quickly to very large numbers of infected people. With this "network" that we would regularly monitor, we’d know that our virus isn’t spreading anywhere in Croatia, and we’d also know how many Croats are infected. Another approach we could take is to start looking for people with antibodies, who apparently have become infected with coronavirus, even though they aren’t aware of it, and then issue them passes and include them in normal life in important roles. However, we will still have to wait for solid scientific proof that immunity against this new coronavirus is indeed permanent.

Virus testing is somewhat comparable to counter-espionage in war. We’re confronted with an enemy who is invisible, and we only become aware of the effects of its actions a week later. In the meantime, we don’t know where the virus is and what it is doing behind our backs. SARS and MERS were significantly easier to control because the infected didn’t transmit the virus before the onset of coughing and other symptoms. With coronaviruses, the infection spreads during the incubation period, while the infected don’t have any symptoms yet, which is a big problem for us. But we can at least resolve it, somewhat, with more active testing.

If we allow it to, the virus will jump from the first infected person to two or three more people, then from each of them to two or three people again, and then do so again. That way, if the first infected person is drawn at the bottom of a piece of the paper, the wider and denser ‘’canopy’’ of infected people is constantly spreading over them, step by step. Through active testing, we’re able to find those who are infected among us. So, we constantly prune that "canopy" to make that situation as rare as possible. If the canopy ceases to spread from step to step because we constantly cut branches wherever we reach, then we’re in coexistence with the virus. We slowly get vaccinated, we treat the seriously ill, and there are fewer and fewer people who don’t have immunity for the virus to be able to jump on.

This way, one can live with the virus present in the environment and thus control the epidemic. What the Director of the World Health Organisation, Dr. Tedros Adhan, tells us is that we must not constantly be on the defensive, in quarantine, and wait for people with symptoms to report for testing. That would mean we're constantly behind the virus. The enemy will then constantly surprise us and strike us from somewhere. That's why it's important to test people as much as possible, but cleverly and reasonably so, and with clear goals.

Quarantine, simply, cannot be a longer-term solution to fighting the virus in Croatia. Initial estimates suggest that about half of Croatian private sector companies cannot withstand this situation for more than a month, and another 43 percent won’t manage for more than three months, which is a terrifying fact. Their exhaustion will also see the end of the filling up of the budget through corporate income taxes, so, there will be no funding for public sector wages either. This will mean that most people now sitting in their homes will no longer be able to buy food, and soon there will be no food to buy, either.

In addition to testing, there are a number of innovative approaches that we may need to resort to in order to be as safe as possible from the virus and escape the Italian scenario of exponential growth. For example, we might initially switch to a work week where people living in house numbers ending in 1 or 2 work on Mondays, those with 3 or 4 on Tuesdays, those with 5 or 6 on Wednesdays, those with 7 or 8 on Thursdays, and those with 9 or 10 on Fridays. This would turn the Croatian population into a so-called "metapopulation", that is, they’d be divided into five smaller non-contact populations. This is similar to a ship or submarine that is internally divided into bulkheads, so they can protect it from sinking if the hull breaks somewhere. That way, we would protect ourselves if the virus somehow triggered an epidemic within one of these populations, it couldn’t then spread to the other four fifths. Perhaps a two-day Monday-Friday work week for everyone would work in an even better way, as it wouldn’t allow the virus to spread day by day, and would still allow us to return to having nine working days a month, with additional work from home where possible. Perhaps even a "one week work, three week quarantine" option would be effective and safe.

The combination of all of these measures: (i) the continuous, active detection of infected persons and their separation; (ii) a "safety net" of 10,000 people for continuous nationwide testing; (iii) splitting the whole of the population into fifths, or working twice a week, on Mondays and Fridays; (iv) various measures to avoid social contact, such as banning large public gatherings, recommendations on wearing masks and gloves, and restrictions on travel and quarantine for arrivals from abroad; and (v) various innovative technological solutions, such as applications that inform all residents of the status of infection of people they have in their contact list, all of which seem feasible. This would probably protect us enough from the virus and allow the vast majority of people to continue, more or less, with normal life as much as possible. Because we need to get out of this quarantine situation as soon as possible and we need to make plans now.

Perhaps this unusual situation will be a historical reminder to both countries and individuals of the importance of self-sustainability and independence from others. It may be that many people in the world left without work because of the economic aspect of this crisis are encouraged to consider moving to cottages or to villages. Now that wireless internet can be accessed everywhere, it doesn't matter where the person on Earth actually lives. But if he has his own garden and his own well, at least he won’t get into the kind of awkward situation that many are now finding themselves in recent times. Perhaps one of the consequences of this crisis will be some new idea of organising the lives of individuals and countries, based on self-sustainability. This would also make Croatia, in general, a more robust country in the face of a number of possible new challenges of the 21st century.

Coronavirus will cause losses for humanity in 2020 on the one hand, but it will reduce those same losses on the other. For example, it will reduce the number of traffic accidents, the number of victims of violence, and deaths from polluted air. In addition, until yesterday, spears were breaking around every percent reduction in fossil fuel use, and now all of a sudden this reduction is forced and massive. In a rather improbable way, this pandemic at least helps combat humanity's climate change problem. In Zagreb, however, self-isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic saved perhaps tens of lives of people who would have perished during the earthquake. If I paid for a ticket to watch a movie with such a scenario, i.e. an earthquake that affects people who are quarantined by a pandemic, so they can no longer be outside or inside, I would feel cheated. But, as the Chinese proverb goes, "There are countless things that cannot be imagined, but there are none that can’t happen.’’

This text was written by Igor Rudan and translated by Lauren Simmonds

For rolling information and updates in English on coronavirus in Croatia, as well as more articles by Igor Rudan - follow our dedicated section.

Igor Rudan: Why We All MUST Stay Home for At Least One Month

As Igor Rudan/Vecernji list writes on the 23rd of March, 2020, if we don't go into quarantine, our healthcare professionals will not have to worry about a few dozen or several hundred people who are suffering from coronavirus more severely, which our system can handle, but several thousand of them, which it can't. All of those differences are now our responsibility.

I have joined forces again with our renowned mathematician, Toni Milun, to explain through this text and the accompanying video why we now all have to stay in our homes for at least a month and strictly adhere to the quarantine guidelines.

Pandemics, like the world wars, are dynamic events with an uncertain outcome. In these times, things can quickly change from stage to stage. When encountering a new, unknown and invisible opponent such as this coronavirus, surprises are always possible. That's why one should be careful, but one shouldn't panic. Only those with ''cold'' heads can make all of the important moves and respond to challenges at the right time, based on reliance on science and proven information.

On the one hand, the virus can always surprise us with its mutation. Random mutations of its genetic instructions can change the severity of the symptoms it will cause when causing an infection. They can also change the rate of its spread among the population. On the other hand, there are several lines of defense at our disposal that, depending on the behaviour of the virus, can be activated at the right time. Compared to the situation only three weeks ago, today, I have to make it clear that the epidemiology profession has significantly changed its perception of the danger of this new coronavirus.

By constantly collecting information from many countries, we now have a better understanding of the way it threatens us. I will try to explain here why the attitude of the profession has changed and why everyone now really MUST stay disciplined in their homes for at least a month.

I've written before that this is already the seventh coronavirus to try to adapt to the human species. The first four cause common colds and have been harmless to humans. The fifth, the SARS epidemic, however, was terribly dangerous. It killed as many as 10 percent of the people it infected. It expanded in 2002 from the Chinese province of Guangdong to more than 25 other countries, but was stopped everywhere on the front line(s) of defense.

The sixth one, the MERS epidemic, was even more dangerous. That killed as many as a third of those infected. It spread from Saudi Arabia to more than 25 other countries. But even then, it was stopped by the front lines of defense. These lines of defense include the isolation of patients and all of their contacts. When the epidemic of the seventh coronavirus, with COVID-19 as its causative agent, erupted in Wuhan in January 2020, it isn't surprising that the epidemiologists' interest was primarily focused on the death rate among those infected.

The reason is that previous death rates for SARS and MERS were so terribly high - 10 percent and 35 percent, respectively.

It was soon realised that the death rate among the most severe cases and hospital patients in Wuhan was about 5-10 percent when it came to this new coronavirus. However, it was only valid for the most severe cases that came to the hospital there, but not for anyone infected in the community. Infected doctors, like most patients in the population, had significantly milder issues. Therefore, it was necessary to determine as soon as possible the rate of death among those infected.

We got our first idea of the actual death rate of infected people when the work of Z. Wu and J.M. McGoogan was published in JAMA back at the end of February. It was based on a major report by the Chinese Centre for Disease Control, based on 44,672 COVID-19 positive patients in all Chinese provinces.

The authors showed that the death rate in the Hubei province was 2.9 percent, but they knew it was unrealistically high. This is because, at the earliest stage of the epidemic, the overwhelmingly severe cases that came to hospitals were tested, and there was no time at the height of the epidemic to test many in the community. A much more realistic estimate, therefore, was among those who tested positive outside the province of Hubei, on the front lines of defense of all other Chinese provinces. This death rate was 0.4 percent.

This means that for every 200 people with COVID-19, if given adequate medical care, only one person would die, or even less than that. Confirmation of that came from South Korea, where an unusual incident occurred. A community epidemic happened there, behind the front lines of defense. The authorities there went forward with en masse testing. Thus, the path of the virus among the population was constantly monitored and all the infected were isolated.

For such a very deep first line of defense, South Korea also had enough money, experience and all the other necessary facilities. 10,000 people were tested daily. Based on the first 140,000 tests, the rate of deaths in the community was estimated to be about 0.6 percent, again - one in two hundred, and quite similar to the estimate for all Chinese provinces outside of Hubei. These two figures are also very close to the estimate I made on March the 1st, that is, when spread among the community, COVID-19's death rate should be between 0.5-1 percent.

In addition to the death rate among all those infected, it was also important for epidemiologists to know what the chances of a cure for all those who end up in hospitals are. It's important to evaluate these prospects when the patients aren't treated in the face of a booming epidemic and during an overload of local hospitals, and the situation in which entire medical teams are infected, but in conditions of being well prepared.

We learned these outcomes from the work of W. Guan et al., Published in the NEJM magazine. On February the 28th, they released a series of 1099 patients with laboratory confirmed COVID-19 infections from 552 hospitals in 30 provinces in China. This was a representative pattern of hospital treatment outcomes for China, in an environment where adequate care could be provided to all those infected. The estimated mortality rate of those with COVID-19 who end up in hospital was 1.4 percent, which was indeed much less than the first experiences in Wuhan.

Based on these two key pieces of information about COVID-19 - that is, in the community, it can lead to the death of only one in 200 infected people and that it kills one in 50 to 100 hospitalised people in hospitals - the epidemiology profession had its breath taken away. It no longer seemed to anyone that we were dealing with such a dangerous infection here. This is evidenced by the reactions of the world stock exchanges: Dow Jones was at 24,720 points on February the 28th, and jumped to 27,087 points by March the 3rd, meaning that it gained 10 percent on the total value in just five days after mortality rates became clearer.

The reason is that stock market investors have been in constant contact with leading epidemiologists over recent days. They were interested in how the situation was developing hour by hour. The view of the epidemiology profession during those five days was that we were likely to suppress the COVID-19 pandemic soon. These were exactly the days when I found myself in Zagreb and gave my first estimates to the Croatian media, after the first COVID-19 patients were recorded here.

The epidemiological profession's view at the time was that the primary epidemic, in the City of Wuhan and in the province of Hubei, had been in continuous decline from February the 8th until the end of February; that the first lines of defense were able to stop the virus in thirty Chinese provinces, each with tens of millions of inhabitants; then that the virus was successfully halted on the front lines of defense in Japan, Taiwan and Singapore, the countries that have the highest human traffic with China.

In addition, even in South Korea, where an unforeseen epidemic occurred in the community, it was managed by intensive testing, with as many as 10,000 tests carried out per day.

The developments were then completely similar to the scenario already seen with SARS and MERS. The same scenario was repeated during the transition from February to March and with the third coronavirus, caused by COVID-19. There was also a primary focal point in the City of Wuhan in the Hubei province. It was suppressed by a large and strict quarantine, as the ultimate line of defense. All secondary foci were controlled by primary lines of defense. None of the epidemiologists thought at the time that EU and US countries wouldn't be able to stop it in the same way.

The epidemic then seemed practically to be extinguished, and even the World Health Organisation delayed declaring COVID-19 a pandemic at all. It did it only about ten days later, that is, on March the 11th, because things had changed to such a dramatic extent. What, then, changed so much between the period of February the 28th and March the 3rd, when the epidemic seemed practically overpowered, and March the 11th, when the World Health Organisation declared a pandemic and the need for the absolute highest degree of caution?

According to the current understanding of the situation that the epidemiology profession can offer, after celebrating the Chinese New Year on February the 12th, about a week later, a number of Chinese workers employed in their textile industry, in northern Italy, returned to Italy. They were tested and recorded at the Italian airports by "first line of defense" measures. However, this seemed to be heard among the Chinese, so many began avoiding direct flights from China to Italy, returning via other European airports that didn't exercise such strict controls. The Italians, however, didn't control flights from the EU. Because of this, an epidemic that no one knew about began to quietly spread in the smaller cities of Lombardy, where many Chinese workers live, and behind the Italian line of defense.

There are many people living in northern Italy who went skiing in late February and early March. Across European ski resorts, they spread the infection enormously to the Swiss, French, Austrians, Germans and Spaniards, as well as citizens of many other countries in northern and western Europe. This is probably also because the spread of coronaviruses is generally favoured by lower temperatures. The current picture of the spread of the epidemic and of the hardest hit countries is in line with these developments.

As I described above, from March the 3rd to the present in many EU countries, most notably in Italy, which was one week ahead of the others, the number of infected people started to increase at an incredible rate. If the virus breaks through the first line of defense, we know that its growth will be exponential, but the human brain can hardly understand what that really means. In linear growth, anything added in the fifth week of expansion will represent one fifth of all cases so far. In the tenth week, a tenth. We know that and it is logical.

But when it comes to exponential growth, everything added up in each coming week will account for the vast majority of all cases, and anything that has happened before will seem irrelevant compared to just one week previously. This is what Tony Milun explains in today's video.