Exploring Croatian - The Oldest Known Slavic Alphabet - Glagolitic

January the 2nd, 2023 - Did you know that Croatia once used the oldest known Slavic alphabet? The Glagolitic script can still be seen in various parts of the country, and souvenirs sold across Croatia still bear it to this very day.

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian. What about Glagolitic?

A (very) brief history

To start off, it's worth noting that the origins of the Glagolitic alphabet are disputed to an extent. This can be said for most ancient languages and linguists are known to squabble over such things, but it is generally accepted that the script was created back during the ninth century by a monk from Thessalonica (today's Thessaloniki in Greece) called Saint Cyril, as well as to Saint Methodius, his brother. The very first observed mention of the word ''Croatia'' in the Glagolitic script dates back to around 1100 AD.

Another interesting fact about Glagolitic is that the precise number of letters in its original form is entirely unknown, but what we do know is that it is likely that Saint Cyril and his brother Methodius created the script in order to facilitate the introduction of the Christian faith, and we can assume with some level of certainty that the initial number of letters would have close to a Greek model. That said, there are elements of a variety of different languages within Glagolitic.

Over the many years, Glagolitic evolved with the population of its users and the tumultuous times they faced. It is certain that during the twelfth century, as Glagolitic in its original form (even with its non-Greek sounds) began to lose its grip, more and more Cyrillic influence could be found. As the centuries rolled on, more and more original Glagolitic letters were dropped, seeing the original number of letters drop to less than thirty in the Croatian recensions of what was called the Church Slavic language.

The use of the Glagolitic script in Croatia

The first Croatian Glagolitic book to be printed was Missale Romanum Glagolitice from 1483, and if you somehow managed to obtain a fully functioning time machine and took a quick trip back to the twelfth century and landed anywhere in Kvarner, Istria, Dalmatia, or even in Medjimurje, you'd have come across the Glagolitic script more or less everywhere. It's true that Glagolitic was mostly found in the coastal parts of the country, with notable areas being islands such as Krk (the Kvarner area) and the Dalmatian islands which sit just off the Zadar mainland, but traces of it stretched to Medjimurje (far inland), Lika, and even in parts of modern Slovenia.

For a very long time, it was accepted that the Glagolitic script was used solely in the aforementioned areas, but when 1992 rolled around and Croatia was engulfed in some extremely difficult times in its fight for independence and against Serbian aggression, some fascinating discoveries were made in old churches situated along the Orljava river in Eastern Croatia (Slavonia). This rather remarkable discovery blew previous theories about the locations in which this ancient script was used out of the water, and proved that it was also indeed used in Slavonia, something that was simply not even considered before.

While the twelfth century was in some ways a form of peak for the old Glagolitic script in Croatia, it did survive beyond that as the nation's main script, and for some time, but after a while, the development (or indeed decline) of this script was very poorly documented for a variety of reasons. Just before the marauding Ottomans began sniffing around the area, and before the Croatian-Ottoman wars truly began, the use of Glagolitic was at its very peak, and in today's measure, the amount of people using it back then would correspond to the amount of people in Croatia who use the Chakavian and Kajkavian dialects (two of the main dialects which make up modern standard Croatian) today.

The Ottoman wars and the decline of Croatian Glagolitic

The Ottomans and their invasions in the surrounding areas sounded the death knell for Croatian Glagolitic, and its stability in the region began to slip severely, with more damage being done to the use of this old script in areas more devastated and culturally altered by the Turkish forces. While the Ottomans certainly laid the heaviest of the groundwork to put the nails in Glagolitic's coffin, the real blow which set the wheels in motion for Glagolitic to meet its fate came much, much later, more precisely in the seventeen century, and by a bishop from Zagreb, no less.

The Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy, the west and the Italians

You've likely never heard of this conspiracy, as it's known in Croatia by this title, but to others it is simply called the Magnate conspiracy. In short, this conspiracy was an organised attempt to remove foreign influences (read Habsburg) from both Croatia and neighbouring Hungary during the seventeeth century. This left the Glagolitic script entirely without secular protection, and its use was severely limited, seeing it used only in the coastal region of modern Croatia. One century later, in the very late part of it, western influence saw to it that Glagolitic was to be no more. The culture and the script crumbled under secular pressures from the west, and it relied solely on printed material. By the time the twentieth century had rolled around and Fascist Italy did its bit in many part of modern Croatia, the areas in which the Glagolitic script had managed to cling on to existence suffered tremendously, and these areas were scaled back even more.

Glagolitic in modern day Croatia

Many ancient buildings, such as churches, still bear the Glagolitic script to this day, and of course, items bearing it can also be purchased across the country. The brand new Croatian euro coins with national motifs on them also proudly bear this ancient script, and it can be found on the 2 and 5 cent coins minted here. The 1992 discoveries in Eastern Croatian churches also shed light on the script, and those churches are in Lovcic and Brodski Drenovac. Some of the oldest stone monuments with the Glagolitic script engraved on them have been found in Istria and on the island of Krk, and in February each year, Croatian Glagolitic Script Day is marked in an attempt to preserve the rich and rather mysterious history of this script for generations to come.

For more on the modern Croatian language, dialects, subdialects, extinct languages, and learning Croatian, make sure to check out our dedicated lifestyle section.

A Brief History Of The Extinct Istrian-Albanian Language

December the 5th, 2022 - Ever heard of Gheg (or sometimes Geg) Albanian? It's one of the two main varieties of the Albanian language, the other being Tosk. Spoken in the Northern and Central parts of Albania, as well as in Kosovo, parts of Montenegro, Macedonia and Serbia, it has over three million native speakers. What does that have to do with Istria, you may ask? Let's get to know the now extinct Istrian-Albanian language a little better.

We've looked into the three main dialects which make up modern standard Croatian as we know it today, Shtokavian, Kajkavian (and Northwestern Kajkavian) and Chakavian. We've delved into dialects and subdialects such as Ragusan (the Dubrovnik subdialect), old Dalmatian, and some very sparsely spoken languages such as Istriot, Zaratin, Istro-Romanian and Istro-Venetian. Istrian-Albanian is now unfortunately entirely extinct, and there isn't that much known about it.

First of all, I should explain that the Istrian-Albanian language ''died'' in the nineteenth century, having arrived on the Istrian peninsula with the ethnic Albanians who moved there between the thirteenth and the seventeenth centuries. The Albanians who spoke this Northern Gheg form of Albanian were primarily settled there by Venice, which had an enormous amount of power at the time and of course then ruled over Istria, in an attempt to combat the increasing issue of depopulation of the wider area.

Of course, other ethnicities and nationalities also moved (or were moved) there by the then mighty Republic of Venice, and they also brought their various languages and dialects with them. This is part of Istria's very long and freckled history which makes it so diverse and rich. If any part of Croatia can be (and has more or less always been) considered to be multicultural, then it is the Istrian peninsula. The sheer amount of ethnicities present there is a testimony to the history of that part of the country.

The various languages and dialects spoken by the settlers of that time eventually saw the evolution of the Istrian-Albanian language, with the only known surviving text written entirely in Istrian-Albanian having been written by the Italian priest, inventor and historian Pietro Stancovich/Petar Matija Stankovic (1771-1852) in the 1830s.

Most sources claim that it was spoken in the very small settlement of Katun (close to Porec) until the nineteenth century, especially given the fact that the very name ''Katun'' draws its origins from Albanian, but there is very little known or officially recorded other than that. The reason for that could be similar to what has been observed with the Istro-Romanian language, in that many of its speakers were peasants who had little to no access to education, leading to the language simply being left to the often cruel hands of time. That said, we do know that the ''original'' version of the Istrian-Albanian languages was spoken in the wider Bar region in neighbouring Montenegro, as well as in and around Skadar in Albania.

Little is left in the modern day in regard to the extinct Istrian-Albanian language, as preservation attempts were never really a motive for anyone, which thankfully isn't the case for languages like Istro-Romanian, with both the Croatian and the Romanian governments attempting to keep it alive.

For more on the Croatian language, as well as the many dialects and subdialects spoken across the country, make sure to keep up with our dedicated lifestyle section.

Zagorje, Međimurje, Samobor and More - The Northwestern Kajkavian Dialect

November the 2nd, 2022 - Iva Lukezic, an expert in the Croatian language and in dialects, states that what's known as the Zagorje-Međimurje dialect or the Northwestern Kajkavian dialect is one of the main dialects of the wider Kajkavian dialect. This manner of speaking is primarily characterised by the preservation of what's known as ''basic Kajkavian accentuation''.

We've looked into enough dialects and subdialects of the Croatian language to realise there's much more to the language spoken in this country than what's now known as standard Croatian. From the Dubrovnik subdialect with its Florentine and Venetian roots, and learning about Kajkavian and Chakavian, to old Dalmatian which is sadly dying with the last generations to speak it, the regional way of speaking across Croatia is extremely varied for such a small country.

Did you know that in some cases it gets a bit more complicated than the three ''main ways'' of speaking (Kajkavian, Chakavian and Shtokavian)? There of course regionalities and variations within each of those, too, and let's not even get started on the words only spoken on certain islands. Let's take a look at the Northwestern Kajkavian dialect, which encompasses several areas of modern Croatian territory.

It is spoken in the border areas of Croatia from Slovenia and Hungary (around Kotoriba below Nagykanizsa and in Prekodravlje) all the way to the City of Zagreb. The Northwestern Kajkavian dialect can be divided into several sub-dialects; spoken in Samobor, Međimurje, Varaždin-Ludbreš, Bednjan-Zagorje and Gornjosutlan. There are some linguists and other experts in the Croatian language and in dialects who consider each of the ways of speaking in the aforementioned locations to be dialects in their own right, and not merely subdialects.

Veering off to be even more specific for a second, it's worth mentioning that the local Bednja(n) dialect is considered to actually be the oldest form of the Kajkavian proto-dialect.

The Bednjan dialect is spoken by the inhabitants of the municipality of Bednja, which, in addition to Bednja itself, encompasses the areas of Pleš, Šaša, Vrbno, Trakošćan (which you'll likely know of thanks to its stunning castle), Benkovec, Rinkovec, Prebukovje, and so on. The Bednjan dialect isn't completely isolated, and most of its main features are also found in certain neighbouring areas like Lepoglava, Kamenica, and especially in Jesenje.

In scientific circles, Bednja speech is unfairly neglected, which makes it all the more important to mention the professor and dialectologist Josip Jedvaj, born in Šaša, who published the most precise and comprehensive study on the Bednjan speech so far in the Croatian Dialectological Collection, which is considered one of the best descriptions of one of the organic forms of speech of this part of the country. The people of the municipality of Bednja named a district school in Vrbno and a street in Bednja after him as a thank you for his efforts to preserve the Bednja language and not let it be lost to the often cruel hands of time, as has been the case for many words spoken in old Dalmatian.

Given the fact that the Northwestern Kajkavian dialect encompasses a fair few places, some (if not most) of which will have variations in their own locally spoken words, we'll look at some more standard words used in this dialect, some of which are still used, and some of which might well be being forgotten in areas like Međimurje and beyond. Some can still be heard in Zagreb, even. I'll provide their standard Croatian and English translations.

Astal - table/stol

Bajka - a thick winter coat/deblji zimski kaput

Cafuta - a prostitute/prostitutka (kurva)

De - where/gdje

Eroplan - plane/avion

Fajna - good looking or pretty/lijepa, fina ili zgodna

Gda - when/kad(a)

Harijada - when something is busy, unorganised or overcrowded/guzva, nered ili cirkus

Jagar - hunter/lovac

Kalamper (kalampir) - potato/krumpir

Laboda - ball/lopta

Marelo - umbrella/kisobran

Nemorut - someone who is useless, lazy or good for nothing/beskoristan ili lijen

Ober - above/iznad

Palamuditi - to talk shit or say stupid things/pricati gluposti

Raca - duck/patka

Senje or senji - dreams/snovi

Tolvaj - thief/lopov

Untik dosta - more than enough/vise nego dovoljno

Venodjati - to have sex or make love/voditi ljubav

Zajtrak (sometimes zajtrek or zojtrak) - breakfast/dorucak

For more on the Croatian language, from learning how to swear in Croatian to learning about the various dialects, subdialects and history of the language, make sure to keep up with our language articles in our lifestyle section.

Swearing in Croatian - The Always Handy, Adaptable S Word

October the 11th, 2022 - So far, our swearing in Croatian series has looked into the dark but always creative depths of the J word, the P word and the K word, and with so many letters still left in the alphabet to explore, I thought we'd look at the S word, which is slightly tamer than some of the rather more eye-opening ones above.

The S word is in Croatian what it also is in the English language, it's shit. Quite literally, shit. It doesn't cross into the threshold of sheep or mouse genitals like the K word does, and it doesn't blow p*ssy smoke quite like the P word does (don't even ask, just click the link above), but despite being rather tame in comparison, it's just as diverse.

Let's begin with the most basic use of this word when swearing in Croatian - sranje, which means shit. Not, under any circumstances, to be confused with ''stanje'' (which is how you'd describe how something stands, such as how much data you have left on your phone plan, what the situation is, or what condition a car you're selling is currently in). Let's delve deeper into just some of the more common ways in which sranje can be used and modified to fit just about any situation.

Sranje - As highlighted above, this is just your basic ''shit''. You'd use it in the exact same way you use it in English. Dropped your phone? Sranje. Lost your debit card? Sranje. Perhaps you're wondering why you're talking all this sranje like I am right now (Ponekad se pitam zasto pricam sva ta sranja). Stepped in... well, shit? Then yeah, sranje.

Usrati se - To use the toilet. You figure out which number this involves, and whether you even need to discuss it with others at all... Alternatively, if you'd prefer not to discuss your bowel movements, you could say something like: Now this is all going to go to shit (Ovo ce sad sve usrati), or, if you're not into surprise parties, you might worry how today is your birthday and you're shitting it (rodjendan mi je i zelim se usrati od straha).

Sasrati se - Go back to being sixteen and attempting to sneak your mum's vodka out to go and drink on a park with your friends and thinking you're the next criminal mastermind because you filled it back up with tap water and she'd never be able to tell, but then she pours herself a glass... Or how about when your boss asks you whether or not you actually did that thing he asked you to do four weeks ago. Or maybe you're a business owner who has failed to declare a few kuna here and there... You might say ''Sasro' sam se kad...'' (I was shitting myself when...) and enter the situation as you see fit.

Srati na veslo - This is that phenomenon when, while performing an action, you or someone else performing said action unknowingly and unintentionally messes something up that has nothing to do with whatever that action was, but the initial action had the misfortune of being in the immediate vicinity of what followed.

Let's say you went to move a heavy table across the floor and in doing so you damaged the tiles. Maybe you moved something closer to you and knocked something else over in the process. It can be used for a variety of situations. If you're a fan of the legendary British sitcom Only Fools and Horses, you'll know of the scene with Rodney and Del Boy and the chandelier. That's one good example.

Nasrati se - To say something stupid or inappropriate and then feel the instant burn of shame or embarrassment in your cheeks. An American tourist once asked if ''they fold the walls back in at the end of the tourist season'' in Dubrovnik. Needless to say, this is a perfect example of where this term fits like a glove.

Srati kao vidra - This one is so funny for me as someone who has celiac disease. You'd use this if you (for some odd reason) want to showcase just how proud you are that you have zero issues with erm... going to the toilet. Never been constipated and are very regular? You'd use this. Had an Indian that you thought you had the stomach lining to handle but it turns out your European internals aren't all that experienced? Definitely use this. Got chronic stomach issues? Salmonella? Norovirus? You get it. This one is for you.

Usrati se k(a)o grlica - You'd use this if you were particularly anxious about something, like you're shitting yourself out of fear or worry to the point where you might (proverbially of course) die of fear (umrijeti od straha). Let's say you remembered something you urgently needed to do and you felt your stomach drop... you might say something along the lines of Ajme, usro sam se k(a)o grlica.

Srati - This could be one of several things. Perhaps you are indeed, using the toilet and have no problem discussing the nature of that experience with a crowd. If expelling some of the content of your guts isn't a topic you tend to talk about all that much, you could use this to say how someone (or perhaps you) is ''talking shit'' or going on about nothing.

Posrati se sam sebi u usta - To end up doing something you said you wouldn't. Let's say your friend who said she would absolutely never go out with that arrogant guy but then you see them together at a fancy restaurant, I guess she posrala se sama sebi u usta.

Prosrati se - To come out with something rather shocking or even unacceptable in a certain situation that really, really doesn't call for it. Let's say you're having dinner with your other half's family and you start talking about something not exactly family friendly. Maybe you told a mildly sexist joke to your boss and the laughs are painfully non-existent. We've all done something embarrassing in front of someone who absolutely shouldn't have seen or heard it.

Srati kvake - This is once again a term you could use when referring to talking shit or perhaps more specifically bullshit. Oh come on, don't talk bollocks/bullshit/shit (Ma daj ne seri kvake!)

Usrati motku - You'd use this if you're referencing messing something up, doing something wrong, putting your foot in your mouth (not literally, unless you happen to do yoga), saying something wrong or something coming out in a way you didn't intend for it to. It is also very often used in situations where something has gone wrong (because of you), and now you've got some unpleasant consequences ahead of you as a result. I've gone and done it again! (Ufff opet sam usro motku).

For more on Croatian language (not just swearing in Croatian, I promise), make sure to keep up with our dedicated lifestyle section.

Swearing in Croatian - The Curious Creativity of the K Word

August the 1st, 2022 - We've explored the infamous J word and the equally infamous P word, and as we make our way through the alphabet (in no particular order, might I add) in our swearing in Croatian series, we need to look at a letter that is just as diverse and creative as both J and P, the glorious letter K.

K is the first letter of the word kurac, which, unlike the letter P which focuses entirely on the female sexual organ, focuses on the male one. And, just like the P word, swearing in Croatian and using the K word can be used in all sorts of situations, in fact, it wouldn't really be out of place in just about any situation your mind can think of. Let's delve deeper.

Isti kurac - Literally, ''the same dick'', but the correct English translation would simply be ''the same shit''. Bottled water and that free stuff you get from the tap? The same shit. All political parties? The same shit.

Za misji kurac - Literally, ''for a mouse's dick''. Struggling to make sense of just when the sexual organ of a small, impossibly cute rodent might be used in a sentence? I'll help you out. ''God, that missed us by a mouse's dick!''. ''That was close! For a mouse's dick!''

Turski kurac - Literally, a ''Turkish dick''. You'd use this when describing someone who is pushy and/or aggressive in their approach. ''He came at me like a damn Turkish dick!''

Truli kurac - Something worthless, useless, a waste of time and energy. Something might also mean someone in this case, too.

Boli me kurac - This is a funny one, it literally translates to ''my dick hurts'', but not in the sense you're thinking. Context is important when it comes to swearing in Croatian. The best way to really translate this would be ''I don't give a shit'' ''Like I give a shit'' ''I couldn't care less'' or ''I'm not bothered at all'' about whatever the issue at hand is.

Pun mi je kurac - ''My dick is full''. No, really. But it doesn't mean it in the literal sense. This is used when you're describing to someone just how much you've had enough of something. It's a bit like saying you're at the end of your rope or you've had enough of something (negative) to last you a lifetime. It can also be used how the Brits use the bizarre measurement of a ''f*ck tonne'' of something. ''She has a f*ck tonne of shoes, surely she can lend you a pair'' would be ''Ona ima pun kurac cipela, valjda ti moze posuditi jedne'' in Croatian.

Kurac od ovce - Quite literally, ''a sheep's dick''. In British English, you'd probably translate this as ''easy peasy'' if you were using the child friendly version, or if you're speaking freely in a room of adults, you'd probably say ''it was a piece of piss'' (which is a very amusing British English term, because urine is a liquid, and I'm not sure how one obtains a ''piece of piss'', but I digress). It's used to describe something very easy, something that was a piece of cake, and sometimes if something (or even someone) was worthless or a waste of time. Again, context is the best thing to look at when dropping sheep genitals into any given conversation.

(S)kurcan - To be listless in some way. To be neither here nor there.

M(a)rs/goni se u kurac - To put it politely, to go forth and multiply. To return to wherever you came from, or to get lost/to piss off.

Kurcina - Something went horribly wrong or in a way it definitely shouldn't have.

Za kurac - Literally ''for the dick''. It's a bit like saying something has ''gone to the dogs'' in British English terminology. It's when something is worthless, pointless, meaningless, or something that has gone to hell/to rot.

Ici na kurac - Used when something is getting on your nerves or irritating you.

Evo ti kurac - ''You're getting nothing.''

Kurac cu to napraviti - ''There's no way I'm going to do that.''

Kurcic - Literally, ''a small dick''. This is used to refer to an unimportant person, particularly in cases when said person thinks they're something special.

Koji kurac? - ''What the f*ck?''

For more on Croatian language and of course, swearing in Croatian, make sure to check out our dedicated lifestyle section.

Swearing in Croatian: The Remarkable Diversity of the P Word

July the 29th, 2022 - Swearing in Croatian isn't quite the same as swearing in English. What makes you sound like an uneducated idiot with a poor grasp of proper vocabulary in the English language is quite the opposite in Croatian. Swearing in English is likely to make the pearl clutchers blush and the Karens come out in full force. Swearing in Croatian is much more acceptable, speaking generally of course, and it is used extremely creatively in many cases.

We're going to take a look, letter by letter, at some ways swearing in Croatian differs quite extremely from swearing in English, and try to explain (in the most politically correct way we can manage), what some of these mean, and in what type of situation they are usually used.

First, let's delve into the P word. We've already looked at the J word in the past, with it being perhaps the most versatile of all Croatian swear words. P is a close second, but then again so is S, and so is K... but we'll look into them all in time. So, back to the P word... The P word is a term which centres itself around the female sexual organ, usually to refer to something bad happening, or as an expression of a negative emotion.

Pizdarija - This is used if ''netko je napravio pizdariju'' (if someone has well and truly f*cked something up) or when something going badly or something unwanted is happening. It can also be used to describe something toilsome that can't be dealt with or fixed very easily, or indeed the opposite of that. Context is your friend here.

A u picku materinu! - Oh God, what have I done?! Oh for f*ck's sake! It can even be ''Ouch!'' when you drop something on your foot. (I won't include the direct translation of this, it's much too vulgar. If you're curious, do Google it).

Ona picka materina - Something you're supposed to fix, deal with or do that you can't do now for whatever reason and the thought alone is irritating to you, particularly if you can't remember something about it.

Dobar u picku materinu - Something that is just great.

Pickotehnicar - A gynaecologist.

Razbiti pizdu - When something collapses, falls, breaks or is in some other way destroyed.

Dobiti po picki - To be beaten up or to get into some sort of (usually) physical altercation in which you lost.

Pizdin dim or pickin dim - Something very easy. It can also be used to describe something useless, worthless, or of very little of either of the aforementioned. If you want to use the much more child friendly term, you could say that something very easy is ''macji kasalj'', which literally translates to ''a cat's cough.'' In British English, these terms would be ''a piece of piss'' (non child friendly) or ''easy peasy (lemon squeezy)'' (child friendly).

Ma idi u picku materinu! - In kinder terms (and if you're actually saying this to another person) it means to go back to wherever you came from, to get lost, to p*ss off, to go forth and multiply. If you're saying this to yourself, it can be an expression of surprise, or anything from ''holy shit'' to ''damn'' to ''f*ck me!'' to ''get out of here, no way!'' to ''jeez!''. Context, as ever, rules.

Mrs u picku materinu - Much like the above, this one has a much clearer intention as it is said to someone else. So, read the first line of the above explanation to catch my drift.

Pizdjen/a - To be in a foul mood, or in some other way defeated and not feeling very positive.

Pripizdina - A similar term to vukojebina, which is literally ''where the wolves f*ck'', meaning some God forsaken, middle of nowhere, rural area that nobody has ever heard of. It's commonly used when you really can't remember the name of the place you're referring to.

Pickarati - To be vulgar, unpleasant, to pout or be in a mood. This term originates from Rijeka, but is more widely used.

Pijan 'ko picka - To be extremely drunk.

Popizditi/Popickati - To lose your mind, to go crazy, to be extremely angry, to lose your sh*t.

Placipicka (sometimes plasipicka) - Someone who is easily scared or spooked. An anxious person who is always worried that something is going to happen to them, or that something bad is going to unfold in general.

Popickatari se - To argue or get into a heated situation with someone, especially in a stupid and primitive way, with vulgar expressions and swear words (such as all of these) being used.

Strasipicka - A coward.

Spickati se - This one has multiple meanings. It can be in reference to how someone has got dressed up (scrubbed up well), or if they've met some sort of misfortune, such as crashing their car into a road sign or falling off their bike into a puddle.

For more letters and to learn more about swearing in Croatian, make sure to check out our dedicated lifestyle section.

Speaking Dalmatian - A Little Dictionary of (Mostly) Forgotten Words

July the 25th - Speaking Dalmatian isn't the same as speaking Croatian. For some people, ''speaking Dalmatian'' begins and ends with using the Split dialect, saying ''a e'' when in agreement with something, swapping the letter ''m'' for ''n'', dropping a ''j'' here and there and throwing in ''i''. I am goes from ''Ja sam'' to ''Ja san'', summer goes from ''ljeto'' to ''lito'', and a man saying I was goes from ''Ja sam bio'' to ''Ja san bija''. Speaking in a vague Split way is far from speaking Dalmatian, so let's look a little bit at just how varied Croatian in general really is.

For such a small country which uses it as their official language, Croatian is diverse. What are usually called ''dialects'' here are often almost entire languages of their own. Put someone from Brac and someone from Zagorje alone together in a room and watch them flounder in their attempts to understand each other when they speak naturally and you'll see what I mean.

Foreigners get their tongues twisted just hearing Croatian being spoken, members of the diaspora who think they can speak the language often arrive scratching their heads because the words grandma and granddad used are rarely ever spoken anymore, and when it comes to speaking Dalmatian, very many have no idea of all of the words which are sadly being lost to the cruel hands of time.

Even when it comes to speaking Dalmatian, there are words used in places on the island of Hvar that nobody would really grasp just next door on the island of Brac, and vice versa, and let's not even get started on the Dubrovnik dialect (Dubrovacki govor/dijalekt) in this article, or we'll be here all day long.

So, let's get to speaking Dalmatian by looking at some old and sadly (almost) forgotten words and what they mean. We'll compare them to the standard Croatian words and see how they differ - sometimes vastly. Let's start illogically, much like many of the rules of language appear to be to a lot of people - with the letter B.

Brav - A sheep or a lamb. In standard Croatian this is quite different, with sheep being ovca and lamb being a janjac.

Bravini konji - Nice looking horses, usually of the draft horse type. In Croatian, a horse is merely a konj, and draft horses (to which this term typically refers) are konji na vucu.

Brbat - To look for something with your hands. In standard Croatian, it would simply be to ''traziti nesto rukama'', but why bother with all that when you can use one word?

Breknut - To tap or knock on something. In standard Croatian, you'd say kucnuti, bositi or udariti.

Brgvazdat - To babble, be chatty and to jabber, or to talk a lot (to go on and on about something). In standard Croatian, this would be brbljati.

Britulin - A pocket knife or a small switch knife. In Croatian, this would simply be a noz, or a nozic if you want to emphasise the fact that it is small.

Bricit/bricenje - To shave and to be shaving. In Croatian, this would be brijati (to shave), or brijanje (shaving). You can also use this term in a context-based way if it's particularly blowy outside thanks to the harsh bura wind, for example.

Brik - A two-masted sailing vessel. In standard Croatian, this would be a jedranjak sa dva jarbola. Again, when speaking Dalmatian (or old Dalmatian), shortening it all is easier.

Briska - Olive pomace, or, in standard Croatian, komina od masline.

Brlina - A location within an oil mill used for the ''pouring out'' of the olives, or, prostor u uljari namijenjen za sipanje maslina.

Bmistra - The Dalmatian word for the Spartium plant (in standard Croatian this one isn't that much different - brnistra).

Brombul - A mix of everything and anything! In Croatian, you'd probably just say mjesavina svega i svacega.

Brombulat - This one ties in with the above as you can see with the similarity of the word used. This would be the act of mixing up that ''everything and anything'' mentioned above. In Croatian, you'd just say mjesati nesto. Isn't speaking Dalmatian so much more simple?

Brontulat - It's similar to the above to read, but it means something quite different. You'd use this if you were speak without any sense (govoriti bez smisla) or to just go on and on about something (neprestano govoriti) without a reason. You might even use this term for someone complaining (prigovarati).

Buhoserina - Literally, flea shit. In Croatian, this would just be izmet buhe.

Buherac - The Dalmatian word for the Tanacetum plant. In Croatian this is buhac.

Buganci - frost bite on the arms, legs or on the lips/around the mouth. In Croatian, this would be ozebline or smrzotine.

Bujer - A hat or cap (kapa, sesir).

Bumbit - To drink (Croatian: piti).

Bunetarka - A type of fig, in Croatian this would be bruzetka crna, or as the Italian is used by those who are into this, brogiotto bianco.

Butiga - This one is still very commonly used. A shop or a place/point of sale. In Croatian, this would just be trgovina. The person actually doing the selling, such as the cashier, would be a butigir.

Butat - The act of throwing something into a body of water, most likely the sea. Baciti nesto would be the standard Croatian version.

As you can see, speaking Dalmatian, or more precisely using old Dalmatian words, is quite different to speaking standard Croatian, and it doesn't begin and end with using a Split dialect. Some of these words (but not all) are rarely used anymore and are in danger of being lost forever - and we've only looked at the letter B so far. So imagine an entire alphabet of words like this which often sound absolutely nothing whatsoever like their standard Croatian equivalents?!

It's up to us to work to preserve this old way of speaking for future generations who want to claim being Dalmatian as part of their heritage and culture. Languages are enormous parts of cultures, and they open doors to connections which would otherwise remain closed to us. It's imperative we keep dying terminology alive.

For more, make sure to check out our dedicated lifestyle section.

People Also Ask Google: What Language Do They Speak in Istria?

February 25, 2021 – Continuing the TCN series answering the questions posed by Google's People Also Ask function, one that confuses many: what language do they speak in Istria?

Where is Istria?

Istria is the biggest and northernmost peninsula in Croatia and the Adriatic. It lies in the northern part of the Adriatic, in Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy. Geographically, 90 percent of the Istrian peninsula is part of Croatia, while nine percent includes Slovenia.

Most Croatians live in the Croatian part of Istria (68,33 percent), while minorities make up a quarter of the population, of which Italians are the biggest group – six percent. In the Slovenian part, Slovenes make up the absolute majority population. Only one percent of the Istrian surface is part of Italy. It includes only two small municipalities near Trieste, of which the majority of the inhabitants in one are Slovenes and in the other are Italians.

According to the 2011 census, 25 percent of people in Croatia declared their regional identity as Istrian, of which 12 percent live in Istria County, one of 20 Croatian counties. The name for a regional identity developed by a part of the citizens of Istria, mainly its Croatian part, is Istrianism. Thus, regional identification is more pronounced in Istria than in other parts of Croatia.

How many official languages are there in Istria?

Since there are two official languages in Istria – Croatian and Italian – Istria is a bilingual community. Italian is the second official language in Istria since 1994, and the Constitution guarantees the rights to bilingualism in Croatia. Out of 208,000 inhabitants in Istria County, 180,000 stated that their mother language was Croatian, while 14,000 of them stated Italian as their mother language.

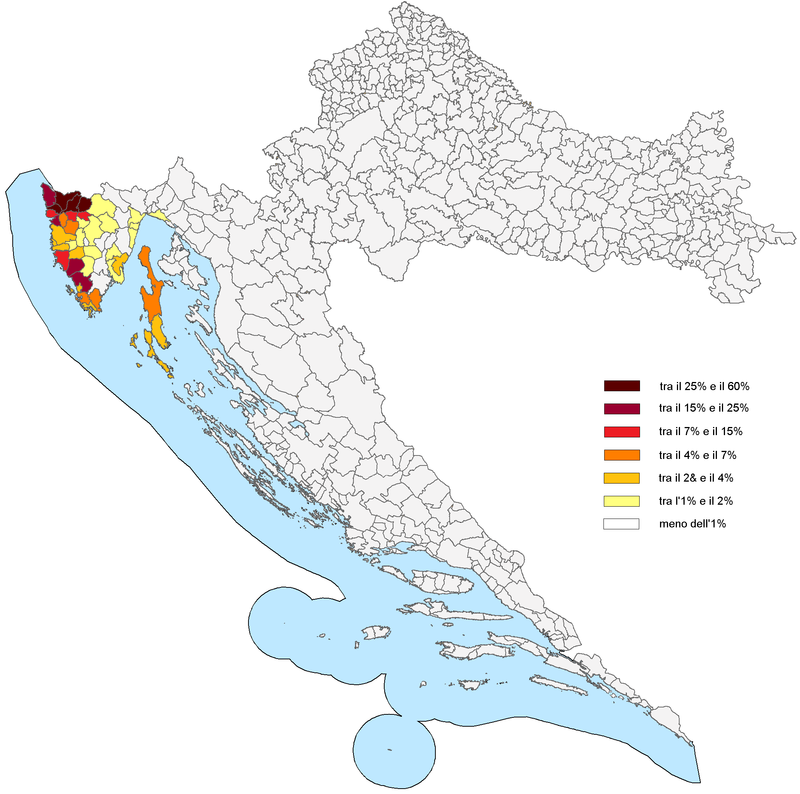

Native speakers of Italian in Croatia according to the 2011 census / Wikipedia

In addition to Croatia's Constitution, local legislation, i.e., the Istrian County Statute equates these two languages in public use and encourages learning Italian as an environmental language. The Istrian bilingual community includes both smaller and larger Istrian settlements.

Due to this bilingualism, Istria is a specific region in Croatia, so there are many Italian public institutions (schools, kindergartens, etc.). Istria has a long tradition of education in another language. Besides, the environment itself is bilingual, which means that Italian is not only spoken by Italians but people of other nationalities too, including Croatians. Also, Istria is historically, culturally, and economically strongly connected with Italy.

Buje, Istria / Copyright Romulić and Stojčić

Reputable cultural, scientific, pedagogical, and artistic minority institutions have been established in Istria: Italian Drama in Rijeka (Dramma Italiano), Center for Historical Research in Rovinj (Centro di Ricerche Storiche), Italian department at the Faculty of Philosophy and departments in Italian for teacher education at the College of Teacher Education in Pula. Also, La Voce Del Popolo, a daily newspaper in Italian owned by the Italian Union (Unione Italiana), is published in Rijeka.

During his visit to Istria last year, Italian Ambassador to Croatia, Pierfrancesco Sacco, said that Italians in Croatia feel at home, like Croats in Italy. This is especially evident in Istria and Pula, where there are a deep friendship and a desire to find new cooperation methods. On that occasion, the Mayor of Pula, Boris Miletić, said that the fundamental values, which have been nurtured in this area for decades, are openness, multiculturalism, and coexistence.

What language do they speak in Istria?

The vast majority of Istrians speak the Croatian language's Chakavian dialect, meaning they use the interrogative pronoun "ča." Only in some parts near the border with Slovenia, some people use the interrogative pronoun "kaj," so they are often mistaken for Kajkavians. Still, the structure and characteristics of these speeches are distinctly Chakavian.

Chakavian dialect is also spoken in Dalmatia. However, the Istrian Chakavian dialect is different from the Dalmatian one due to the numerous Italianisms. It is also difficult to understand it in the rest of Croatia. The most widespread Chakavian dialect in Istria is the Southwestern Istrian dialect. There are also Buzet, Northern, Central, and Southern Chakavian dialects in Istria.

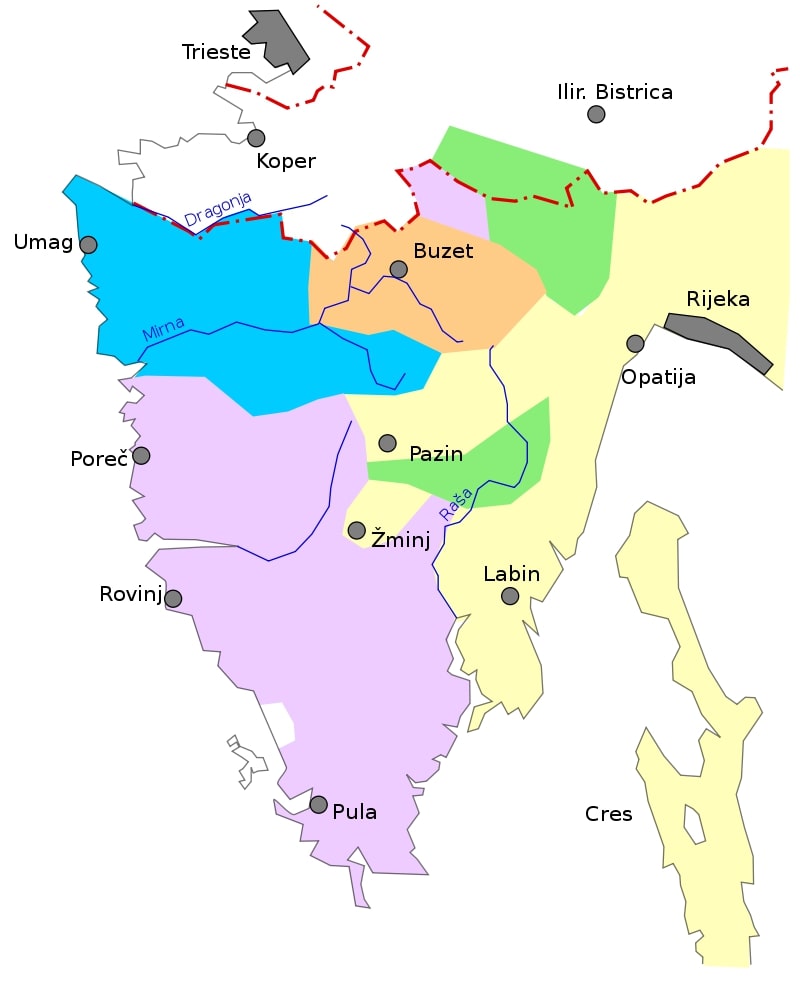

Chakavian dialects in Istria: Southwestern (purple), Buzet (orange), Northern (yellow), Central (green), and Southern Chakavian (blue) / Wikipedia

The aforementioned Italian minority lives in some towns on the Istrian west coast and in some villages near Buje, and they speak Italian. In the Slovenian part of Istria, the Slovenian language is spoken.

In the eastern part of Istria, at the foot of the Ćićarija mountain, in several smaller villages live Istro-Romanians or Ćići, a population of Romanian origin who speak their own Istro-Romanian language, which is a mixture of Romanian and Croatian. Today, many of them have adopted the Croatian language and are now considered Croats.

In addition to the dominant Croatian and Italian languages, other minority languages are spoken in Istria, namely Serbian, Bosnian, Slovenian, Albanian, and Macedonian. One can hear the Shtokavian dialect in Istria as well.

What language do they speak in Istria? Istro-Romanian language

Istria is home to two of the 20 most endangered languages in the world by UNESCO – the Istro-Romanian language and Istriot.

Istro-Romanian language is a Balkan Romance language spoken by only a few hundred people today in the northern Istrian villages of Žejane, Lanišće, and Šušnjevica. It is highly similar to the Romanian language, and for some linguists, the Istro-Romanian language is considered a dialect of Romanian. People in Istria who speak it are called Rumeri, Rumeni, Vlachs, or Istro-Romanians. Croats disparaging started to call them Ćići or Ćiribirci.

In the middle of the 15th century, the Ćiribirci were settled by Ivan VII Frankopan from Velebit on the island of Krk. Since the Ćići plundered Ivan Frankopan in northern Istria in 1463, when their name is first mentioned, it is believed that they immigrated to Istria from Krk. However, Istro-Romanians are not officially recognized as a national minority in Croatia.

The most interesting fact about the Istro-Romanian language is that it was spoken by one of the most famous inventors of all time – Nikola Tesla – even though he wasn't even aware of the ethical existence of the Istro-Romanians. Since elementary school, Tesla was able to speak the Istro-Romanian language, despite the fact that Istro-Romanian was not taught in schools in those years. It was only spoken by a few thousands of people in Istria and Lika, and he could have probably learned it in his family.

Although Telsa always considered himself a Serbo-Croat, one Romanian academic, Professor Moraru, thought Tesla was an Istro-Romanian. When Romanian scholars contacted Tesla in the early 20th century and explained he was of Istro-Romanian roots, he allegedly showed amazement but did not comment on that matter. Therefore, Nikola Tesla has never denied the possibility of his Istro-Romanian origins.

What language do they speak in Istria: Istriot language

Istriot language, often confused with Istro-Romanian language, is a Romance language spoken by about 400 people in the southwestern part of Istria, particularly in Rovinj and Vodnjan. Still, it is also preserved in Bale, Fažana, Galižana, and Šišan. It should not be confused with the Istrian dialect of the Venetian language either.

According to some estimates, the Istriot has only a few dozen active speakers and about 300 people who understand it and can use it in part. It is a Romance language related to the Ladin populations of the Alps, currently only found in Istria. Its classification remained mostly unclear, but in 2017, it was classified with the Dalmatian language in the Dalmatian Romance subgroup.

Historically, its speakers never referred to it as "Istriot language." Instead, it had six names after the six towns where it was spoken: in Vodnjan it was named "Bumbaro," in Bale "Vallese," in Rovinj "Rovignese," in Šišan "Sissanese," in Fažana "Fasanese," and in Galižana "Gallesanese." The term Istriot was coined by the 19th-century Italian linguist Graziadio Isaia Ascoli.

Younger Italians in these places mostly understand Istriot, but they rarely use it, and Croats rule this idiom very badly or not at all. It is most endangered in Fažana, and it seems that it is most strongly maintained in Bale.

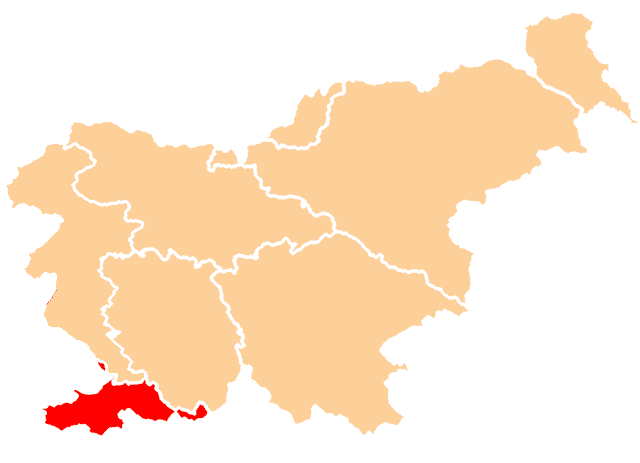

What language do they speak in Istria: Istrian dialect in Slovenia

Slovene dialects are separated into a few groups, and the Istrian dialect, spoken in Slovene Istria, falls in the Littoral dialect group. Istrian dialect is spoken in the rural areas of Koper, Izola, and Piran. The Slovenes living in the Italian municipalities of Muggia and San Dorligo della Valle, as well as in the southern suburbs of Trieste (Servola, Cattinara). In Croatia, it is also called the Slovenian-Istrian dialect.

The dialect has been influenced by Croatian as spoken in Buzet and Ćićarija and is further subdivided into the Rižana and Šavrin Hills subdialects.

Slovene Istria / Wikipedia

Rižana subdialect (yellow) and Šavrin Hills subdialect (green) / Wikipedia

The Rižana subdialect is spoken in the northern part of Slovenian Istria, in the Rižana Valley east and north of Koper, including the settlements of Bertoki, Dekani, Osp, Črni Kal, Presnica, Podgorje, and Zazid. In Italy, Rižana subdialect is spoken in most of the municipalities of San Dorligo della Valle and Muggia south of Trieste and some southern suburbs of Trieste, especially Servola.

The Šavrin Hills subdialect is spoken in the Šavrin Hills south of a line from Koper to the south of Zazid. It includes the settlements of Koper, Izola, Portorož, Sečovlje, Šmarje, Sočerga, and Rakitovec.

The mixture of Šavrin dialects proves the closeness to the Čakavian dialects, and the Rižana sub-dialect is entirely Slovene. There are many Romance loanwords in both sub-dialects linguistic legacy, mostly Venetian, Trieste-Romance, and Italian.

Why do locals speak Italian?

As previously explained in the second paragraph of this article, Croatians in Istria speak Italian because it has been implemented in public speech and institutions for such a long time.

As Marija Črnac Rocco, head of the Rovinj City Council office, explained for Novosti portal, the Italian national minority in Istria (and certain other Croatian parts) is autochthonous, meaning that the Italian component has always lived and existed in these territories.

Likewise, Italian was the official language during all the various reigns in Istria until the end of the Second World War – the Venetian Republic, the Kingdom of Austria, Napoleon's rule, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, and the Kingdom of Italy.

Rovinj, Istria / Copyright Romulić and Stojčić

After the Second World War, Istria was annexed to the Federal Republic of Slovenia and Federal Republic of Croatia, namely the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The Italian national community's position, which became a minority in a significant part of Istria due to sad post-war circumstances, has been the subject of consideration and securing the rights of many international agreements.

Therefore, the equal use of the Croatian and Italian languages in Istrian County and many towns and municipalities in Istria is undoubtedly a legal obligation, which for most Istrians is both a moral duty and a civilizational achievement of which they are proud.

Bilingualism in Istria is not only lived in translated official documents, it is lived in families, on the street, in everyday communication, in traditions, and customs. Bilingualism in Istria is natural, spontaneous, and it is perceived as an advantage and a richness.

Istria in Italian and Croatian: some important bilingual place names

Istrian County has ten cities and 31 municipalities. When you drive through Istria, you will notice bilingual traffic signs, including both Croatian and Italian names of towns and municipalities, such as:

- Buje – Buie

- Buzet – Pinguente

- Fažana – Fasana

- Grožnjan – Grisignana

- Labin – Albona

- Medulin – Medolino

- Motovun – Montona

- Novigrad – Cittanova (d'Istria)

- Pazin – Pisino

- Poreč – Parenzo

- Pula – Pola

- Rovinj – Rovigno

- Umag – Umago

- Višnjan – Visignano

- Vodnjan – Dignano

- Vrsar – Orsera

- Žminj – Gimino

As such, in Croatian, we say Istra, and Italians say Istria.

When was Istria a part of Italy?

Istria was a part of the Kingdom of Italy after the First World War when the Austro-Hungarian Empire disintegrated. In 1920, with the Rapallo Peace Treaty, Istria, the Croatian city of Zadar, as well as the islands of Lastovo, Cres, and Lošinj, belonged to Italy. Rijeka belonged to Italy in 1924. During the Second World War, the population organized a movement of resistance to fascism by Benito Mussolini. Therefore, after the war, Istria became part of Yugoslavia, where it remained until its disintegration in the early 1990s when the Istrian peninsula was divided by Croatia and Slovenia.

During the 19th and the first half of the 20th century, a significant Italian linguistic and ethnic community in Croatia mainly concentrated on the west coast of Istria and in Rijeka, Dalmatian, and Kvarner towns. After the First and especially after the Second World War, most Croatian Italians emigrated to Italy.

Grožnjan / Copyright Romulić and Stojčić

Today, almost three-quarters of all Italians in Croatia live in Istria County. The only municipality in Croatia where Italians make up a relative majority is Grožnjan in Istria, with 39.4 percent ethnic Italians in the population and 56 percent of the people whose mother language is Italian.

The Italian community's position and rights are guaranteed by the Constitutional Law on Human Rights and the Rights of Ethnic and National Communities of the Republic of Croatia, as well as various international agreements and treaties.

To follow the People Also Ask Google about Croatia series, click here.

Slavonia Students Spot 300 Spelling Mistakes In Names of Public Places

November 21, 2020 - How difficult is it to learn Croatian? Slavonia students from one high school learned it's really not so easy for people to correctly use their own language

How difficult is it to learn Croatian? Well, it's pretty difficult. Croatians know this best of all and will be reasonably impressed if you make any advances in trying to speak their language. A professor of linguistics from Zagreb University once told this writer that to be able to regard yourself as wholly proficient in the Croatian language, you would have to study it to no less than university level. Naturally, not every speaker of Croatian has done so.

Slavonia students from a high school in Slavonski Brod were recently tasked with looking for mistakes in the use of Croatian language in public places. So complex is the Croatian language, spelling and grammar mistakes are commonplace. The teacher assigning the task, Vesna Nosić from Matija Mesić high school, was no doubt confident her students would uncover some mistakes. However, the grand total of 300 spelling and grammar mistakes the Slavonia students found is possibly more than was bargained for. Particularly as those found were all assigned to public places. Matija Mesić high school in Slavonski Brod, where Slavonia students made their findings © Matija Mesić high school

Matija Mesić high school in Slavonski Brod, where Slavonia students made their findings © Matija Mesić high school

The misspelling or incorrect translation of food items on a restaurant or tavern menu is a regular cause of amusement in Croatia. But, the mistitling of public places - streets, squares, companies, monuments, traffic signs and even schools – is perhaps more surprising. These are places you walk past every day.

The Slavonia students were given the high bar of the official standards of Croatian language set by the Institute of Croatian Language and Linguistics. Their teacher, Vesna Nosić, has published their findings in the popular science journal Hrvatski jezik (Croatian language), which is published by the institute. Croatian language is something of a national obsession in Croatia, its acceptance as the official language very closely linked to the country's struggle for autonomy. For most of its history, the lands of modern-day Croatia were controlled by empires for whom Croatian was not their language. The use of foreign tongues has been imposed on the population of Croatia for centuries.

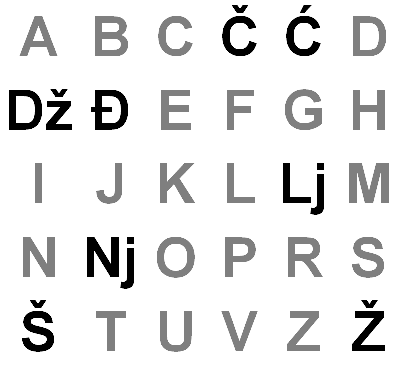

The most common mistakes made in the Croatian language are related to the incorrect use of the sounds ć and č, đ and dž. The letters here come from Gaj's Latin alphabet, devised by Croatian linguist Ljudevit Gaj in 1835. It is the Latin script used across the region in which to write the similar languages of Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, and Montenegrin (in Bosnia, Serbia and Montenegro, the Cyrillic alphabet is used as well as Gaj's Latin alphabet).

The contemporary version of Gaj's Latin alphabet (it originally contained Dj, which was replaced by đ. This alphabet ihe easiest part of learning Croatian - within 15 minutes, almost anyone can correctly pronounce all Croatian words by using this. In comparison to the Latin alphabet used by English speakers, the letters q,w,x,y are omitted. Instead, we get the additional č, ć, dž, đ, lj, nj, š and ž. Looks difficult? It isn't. Almost all of these sounds exist within the English language. Except for lj which, to English speakers, is torturously missing some kind of vowel © Albatalad

Mistakes between the ć and č or đ and dž sounds are understandable if you can pronounce Gaj's Latin alphabet. And anyone can. The easiest part of learning Croatian is Gaj's Latin alphabet – all of the sounds exist within the English language, all of the letters are always pronounced in exactly the same way (unlike English). The difference in sound between ć and č or đ and dž in spoken Croatian is difficult to perceive if you are not a native speaker (often, even if you are!)

Some of the mistakes found by the Slavonia students are perhaps more forgivable – the standard of Croatian their comparisons was made against is rigid. Thus, pekarna (bakery) instead of pekarnica, or dućan (shop) instead of trgovina were classed as mistakes, but are actually in everyday use on streets across Croatia.

Other mistakes found relate to grammar, spelling and the misuse of upper case or lower case lettering. For instance, Ulica Pavleka Miškina should be written Ulica Pavleka Miškine (the word ending changes to denote it is the street of Pavlek Miškina), Crkva Gospe od brze pomoći, should be crkva Gospe od Brze Pomoći; Muzej Brodskog Posavlja should be Muzej brodskoga Posavlja and Šetalište Braće Radić should be Šetalište braće Radića (denoting it is the promenade of the Radić brothers). Not sure which words should be in upper case or lower case in Croatian? Write everything in upper case - problem solved! © Slavonski Brod Tourist Board

Not sure which words should be in upper case or lower case in Croatian? Write everything in upper case - problem solved! © Slavonski Brod Tourist Board

Sitting to one side and watching how others do something, judging them, then informing them they are doing it incorrectly is not the most pleasant way to occupy your time. However, for the purposes of this study, this not-uncommon activity in Croatia is exactly what was asked of the Slavonia students. However, as noted in today's coverage of this story in Index, there is a great saying in Croatian that serves as a response to any unwanted judgments coming from those on the sides - “clean up the trash in front of your own doorstep before you discuss that which lies in front of your neighbour's”. And, that's exactly what the Slavonia students did – and found out that the name of their own school was spelled wrong.

Lost in Translation in Croatia: Bears, Acid, and Worm Appetisers

August the 4th, 2019 - It's been a long time since I've done one of these, partly because these linguistic gems are getting more difficult to find and can be a little repetitive, and partly because more serious matters in Croatia have taken priority. The tourist season is in full swing, and now, amid the million and one ways to spell pomfrit, now is the perfect time to get Lost in Translation in Croatia once again.

This is a notice about the water being cut off as there will be works taking place. Please let the tenants understand, sure, but who is going to tell them if not this sign?

You can purchase an entire cafe here every single morning, and even get a bear or two to go with it. Not bad.

One of the things tourists love to take home from Croatia are original products, made in the country, and not cheap Chinese crap that falls apart after a week or two. Original products of Craotia are even more desirable.

Ah, what could be better on a hot summer day than a fresh salad. There are many different types of salad on offer in Croatia, and each one tastes better than the last. I imagine it would be the experience of a lifetime to get a bowl of acid to take while in a restaurant.

The Church of St. Rock. The Church of St. Roll is just around the corner.

Who doesn't love a worm appetiser when you're starving and desperate for your main course? This is apparently a restaurant for blackbirds.

There's nothing worse than someone who doesn't ''kept a place clean'' following a long necessity. The sh*t emoji speaks volumes.

I'm not sure if you can buy bears here at Time Aut, but I've got a feeling you can... Not sure why...

The toilet key can be found by the cash register/checkout, not on the casing.

Well, at least you have some privacy and a seemingly gorgeous view while ''paring''. Have fun!

Where to begin with this one... You can go to Slsak (Sisak), Noralja (Novalja), Hvai (Hvar), Tucapi (Tucepi), or even the beautiful island of Mijet (Mljet), among several other strange places, including Poogora (Podgora). I don't know who manufactured this towel, but, well... You come to your own conclusions.

From paring to parkirking, you can do it all in private in Croatia.

This company doesn't like the letter ''r'' in any language. Perhaps the owner has a short tongue.

Both German and English are weak points for this exc(h)ange office!

Speaking of German, it might be wise to go and practice over in the beautiful, popular city of Fran(k)furt. You can get there for a fair price by bus!

Even the Croatian on this one is wrong. ''Prireme'' should be ''pripreme'' and in English, it's asking you to please use small change (coins) and not notes.

I'm not really sure where the word ''located'' has come from here, but what it is saying is that you can't bring unregistered guests to this apartment, that making loud noises after midnight is prohibited, so as not to disturb the peace, and that to register, you need to register with the police who deal with foreigners. Theirs is much funnier, however, despite the apparent shortage of peace and the need for the involvement of foreign police.

Make sure to follow our dedicated lifestyle page for more language fails in Croatia, both by native Croatian speakers when speaking English and by foreigners learning Croatian. If you like the Lost in Translation in Croatia series, have a look at our others by clicking here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.