June 3rd, 2021 - Hailed as the EU’s “port of diversity” after its designation as European Capital of Culture in 2020, Rijeka literally means “river”, or “fiume”, in Italian. But what Italian heritage is left in “the city that flows”? Is Fiume Italian or not?

If you’ve ever been to Trieste, one of the first things that will strike you on the first visit to Rijeka is how similar they look. Austro-Hungarian buildings, a lively city port that opens up into the clear blue of the Adriatic, a lot of city green, the hills sprawling behind it, the mix of languages, the traffic (!). There are indeed many things that Trieste and Rijeka have in common. So the question isn’t entirely out of place: is Fiume Italian or not? What Italian heritage is left in what is now Croatia’s third-largest city?

The Korzo. Photo Sabrina Fusari

Literally, Rijeka means “river”. This may be part of the reason why Italians still call it “Fiume”. Actually, this name dates back to imperial Roman times, when Augustus rebaptised the old Trsatica “Flumen”. But the issues of the borders between Italy and former Yugoslavia weren’t actually settled until 1975, and it’s still a burning wound for many Italian families that fled or were forced to leave the area after World War II. This major tragedy went down in history as the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus. Many also lost their lives, as a yet unknown number of local ethnic Italians were killed or summarily executed. So the question “is Fiume Italian or not?” isn’t entirely controversy-free for either side involved, even in 2021.

Interested in finding out more about Rijeka? Click here.

The Fiume question

The controversy is centuries old. Rijeka was an autonomous city at several stages in its history, starting from 1719, when Charles VI proclaimed it a free royal port within the Habsburg Empire. Apart from a short spell under Napoleon’s rule, and two decades under the Kingdom of Croatia, after Ban Josip Jelačić’s had conquered it, Rijeka enjoyed a high level of autonomy and prosperity. It was also at the crossroads of different languages and cultures, especially Italian, Croatian and Hungarian.

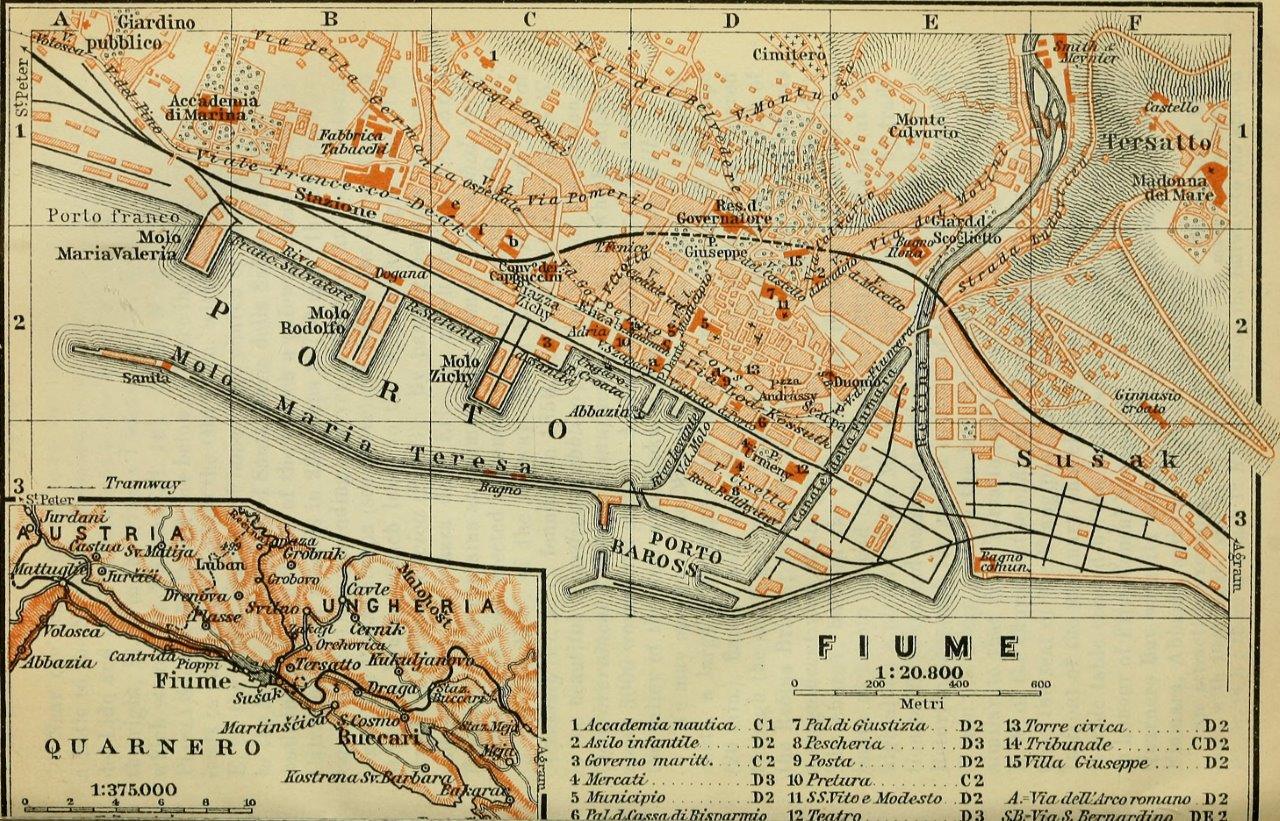

Map of Rijeka from the Italian Baedeker Handbook for Travellers, 1911. Photo Karl Baedeker. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

World War I and the “unredeemed borderland”

Just before World War I, Rijeka’s population was 48.6% Italian, 25.9% Croatian and 13% Hungarian. This is why the Fiuman dialect has historically retained traces not only of Italian but also of čakavski, German and Hungarian. However, this free multinational and multilingual city was also one of Italy’s so-called “unredeemed borderlands” (terre irredente). Therefore, the then young Italian state saw it as highly symbolic and hoped to integrate it into its territory. Italy had seen the partition of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after World War I as the ideal opportunity to achieve this goal. Yet, the Paris Peace Conference (1919) did not settle the issue, as both Italians and Croats claimed sovereignty over Rijeka.

Stamp depicting Gabriele D’Annunzio, 1920. Photo Stan Shebs. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Gabriele D’Annunzio

The dispute ended in a military occupation led by Italian soldier-poet Gabriele D’Annunzio on 12 September 1919. This date still makes a lot of meaning to the city of Rijeka. However, the kind of meaning it makes is very different for Italian neo-fascists, who still claim the city to be a part of Italy. D’Annunzio’s “Fiuman adventure” did not last long (it ended on 24 December 1920) but it sowed the seed of what would materialize 4 years later as the fascist occupation of Rijeka. D’Annunzio had actually galvanized Italian proto-fascist nationalists by refusing to sign the first Rapallo Treaty (November 1920) under which Rijeka became a “corpus separatum delimited by the boundaries of the town and district of Fiume” - so, again, an autonomous city. Despite having gained Gorizia, Istria, Trieste, Zadar and the islands of Cres, Lošinj, Lastovo and Palagruža, for D’Annunzio and his “arditi” (a military corps, literally “the daring ones”) this was still a “mutilated victory.” The controversy is still so heated that, in May 2021, a D’Annunzio statue celebrating irredentism and the occupation of Rijeka was vandalized.

Italian-Yugoslav border on the Dead Channel in Rijeka, 1933. Public domain via Wikimedia commons.

The fascist occupation and the “Dead Channel”

During the fascist occupation, only Sušak remained in Yugoslavia, as the fascists claimed it was the only municipality of the area where Croats were the majority. The border was placed on the so-called Mrtvi Kanal (“Dead Channel”), near the Hotel Continental. This interesting name for a channel identifies the original bed of the river Riječina, which had been deviated in the nineteenth century to prevent floods. This dock building work left that area of the Rijeka port “dead”, i.e. an auxiliary basin, secluded from the rest of the harbour. The Italian translation of Mrtvi Kanal, “canal morto”, is itself a Venetian seamanship term, identifying the original streambed of a water basin.

Eventually, the existence of the Dead Channel state border originated the idea that the city was “Fiume” to the west of the bridge, and “Rijeka” to the east. This adage is quite debatable historically, but it can still be heard in popular culture today. The border itself was closed in 1946, but only a year later was Sušak reunited with Rijeka, under the Paris Peace Treaties. However, the border dispute with Italy was not definitively settled until 1975, with the Osimo Treaty.

Vrnjak, now a ghost town, inhabited by Italians before the exodus. Photo Robert Krajcar & Martin Močibob via Abandoned Croatia.

World War II and the Italian exodus

Meanwhile, a yet unknown number of Italians left the area, were ethnically cleansed or killed in reprisal, changing Rijeka’s language and culture landscape in ways that are still being researched by historians, architects and sociologists. This is still a very contentious issue, not only in Croatia but also in Italy. For sure, the exiles weren’t as gracefully welcomed to the homeland as it’s typically reported in the official version of this history. For example, on 18 February 1947, a train packed full of exiles arriving from Istria was assaulted at Bologna main station. An infuriated crowd of railway workers and passers-by threw stones and prevented the passengers to get off. The mob shouted insults at the refugees, openly accusing them of being runaway fascists until the train had to leave for another destination. Others faced an even crueller destiny, being massacred or sometimes even thrown alive in the foibe, the deep natural sinkholes typical of the Karst region. The actual number of people who lost their lives so tragically is still officially unknown, as estimates range from millions, according to far-right Italian politicians, to several hundred, according to a few left-wing former partisans. Regardless of how many Italians were actually murdered, what is striking is the similarity between the narration of their own experience and more recent reports of ethnic cleansing in other parts of Croatia during the Homeland War.

Street art in Rijeka. Photo Sabrina Fusari

Vestiges of Italy in Rijeka today

In 2019, after an incident during which an Italian flag was raised at Trsat Castle, mayor Vojko Obersnel answered the question “is Fiume Italian or not” in no uncertain terms: “Rijeka is a Croatian city and always will be”. However, the city still has a sizable number of Italian speakers, and a vibrant Italian culture, as we review below.

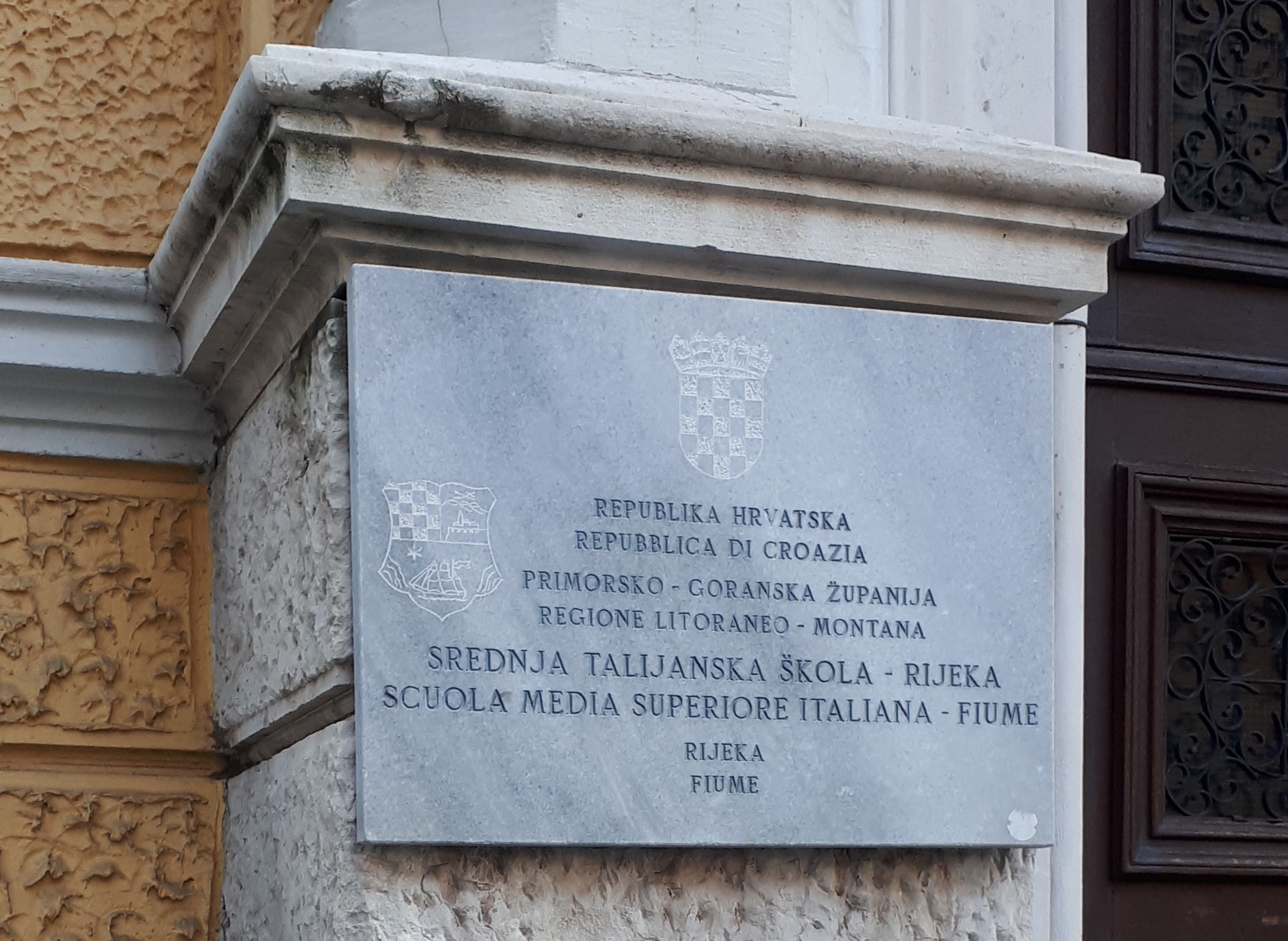

Italian High School Rijeka. Photo Sabrina Fusari

Bilingualism

In comparison with about a hundred years ago, today’s Rijeka has a minority of Italian speakers: the 2011 census recorded 3,429 mother-tongue Italians in the region, as opposed to 26,564 in 1900. However, the situation may be more complex than the raw figures suggest, as many social factors are at play in deciding what languages are spoken at home and handed down to younger generations. Official Croatian-Italian bilingualism was abolished in Rijeka in 1953, but Italian - or, more frequently, a variety of the Venetian dialect - can still be heard spoken in the streets. Italian words are occasionally dropped in also in Croatian conversation. It’s actually very easy for Italian tourists in Rijeka and its coastal region to communicate with locals in their own language without any problems in almost all situations. Double-language road signs are also quite widespread, especially in the city centre. The debate whether both names, “Rijeka” and “Fiume”, should appear on road signs at the entrance to the city, however, goes on to this day. Recent research suggests that trilingualism is also quite common in Rijeka, with families switching from Croatian to Italian and Fiuman, depending on how formal the conversation is. These households use Croatian as the official language, in all situations, Italian in semi-formal settings, and Fiuman almost exclusively at home.

Italian High School Rijeka-Fiume. Photo Sabrina Fusari

Schools

There are many Italian schools in Rijeka: 6 kindergartens, 4 elementary, and 1 high school including 5 different strands: general, linguistic, scientific, touristic and commercial. All follow the Croatian national curriculum, and all subjects are taught in Italian, apart from Croatian language and literature, as well as foreign languages.

In the past few years, the kindergartens have taught 127 pupils a year, the elementary schools about 80, and the high school about 160.

Do you want to find out more about the Italian High School in Rijeka? Listen to the pupils’ own voices in this video.

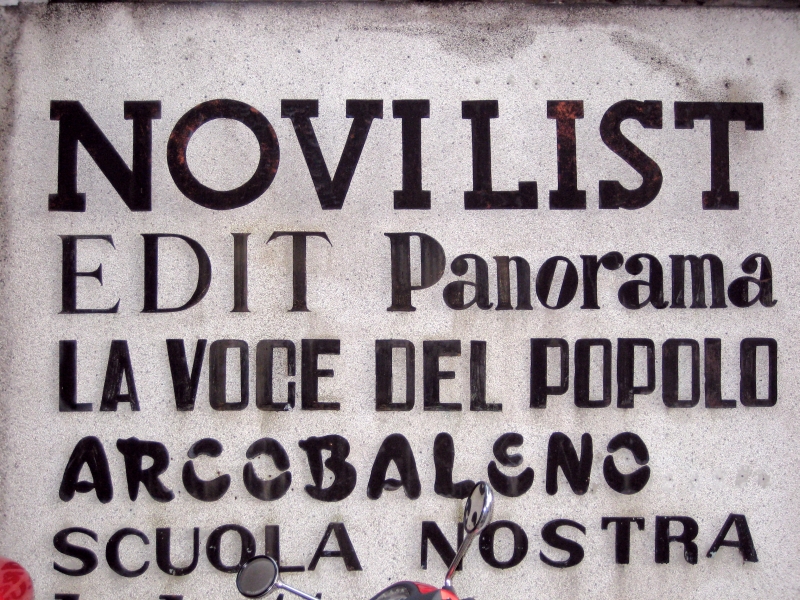

EDIT

But perhaps the sturdiest stronghold of Italian culture in Fiume today is its Italian publishing house, EDIT. Its headquarters and bookshop are well visible in the heart of the Korzo. Founded in 1952, EDIT is a nonprofit organization owned by the Italian Union of Croatia and partially funded by the Croatian, Slovenian and Italian governments. Its main aims are to fulfil the right of access to information for the Italian-speaking minorities of Croatia and Slovenia, and to protect the cultural and linguistic identity of the Italian communities in these two countries.

EDIT publications, 2007. Photo Roberta F. via Wikicommons licence.

Besides schoolbooks and 10 book collections encompassing both fiction and non-fiction, EDIT also publishes the only Croatian newspaper in Italian, La Voce del Popolo (The Voice of the People), and 3 magazines, including a literary one (La Battana, named after the traditional fishing boat of Rovinj) and a monthly children’s picture book (L’Arcobaleno, The Rainbow, formerly entitled Il Pioniere, in Yugoslav times). The Italian Union of Croatia also owns a radio that broadcasts in Italian, Radio Fiume, but the main outlet of Italian language and culture in today’s Rijeka is undoubtedly La Voce del Popolo.

National Theatre Rijeka. Photo Antonio199cro via Wikicommons licence.

The Italian Theatre

However, Italianness wouldn’t be such without a big role for the arts. Interestingly, the Italian Theatre in Fiume has been the only theatrical company allowed to go on performing Italian drama even during the pandemic, as theatres in Italy were closed for over a year due to COVID-19. At the time of writing, theatres in Italy have just partially reopened, with many limitations, while Croatia has always maintained a more flexible policy on this matter. This has allowed the Dramma Italiano di Fiume to keep this fundamental tenet of Italian culture alive over the past year and a half. The Dramma stages many different genres, both classic and modern, Croatian, Italian and international. Besides professional actors, non-professional acting groups, including ones for children, also perform with this company. For example, on stage at the time of writing is Siniša Novković’s Adriatico/ Adriatiko, a musical comedy about the Adriatic sea, performed in cooperation with the City Youth Theatre of Split.

Do you want to watch the trailer for Siniša Novković’s Adriatico/ Adriatiko? Click here.

Sunrise on the Riva Boduli. Photo Sabrina Fusari

Fiuman Local Literature

Despite what we have seen above, EDIT is not the only publishing outlet for the Italian language and culture in Rijeka. Just about a year ago, a book entitled Il dialetto fiumano. Parole e realtà (The Fiuman Dialect. Words and Reality) was published by the Council of the Italian National Minority of the City of Rijeka, in cooperation with the local University. The aim of this project is to deliver recent research and information on the current status and perspectives of the Fiuman dialect as still spoken in Rijeka. What better way, then, to conclude this overview of whether Fiume is Italian or not than a poem in the local Italian dialect, translated into English for Total Croatia readers?

Cavaliere DI GARBO (Gino Antoni) 1877-1948

La nostra lingua Per far sti versi mi o misiado insieme Lagrime con sorisi in una tecia, E ve o buta – co sto miscuglio freme – Un fia de lingua de la zita vecia. El sofrito l’o fato con zivola, Grasso nostran e pevare abondante. Cussi la lingua che ve porto in tola La xe, se sa, un poco pizigante. La xe la lingua de la nostra gente, Con ela, mama, ti m’ha oferto el sen, Con ela el cor, Nina, parlar te sente. Con la mia lingua, cha dispreza el fren, Mi ve ripetero eternamente: “Fioi, semo in pochi, volemose ben!” |

Cavaliere DI GARBO (Gino Antoni) 1877-1948

Our language To write these verses I’ve mixed together tears and smiles in the same jar, and I’ve poured – blending in this mixer – a sniff of my old city’s patois. I’ve stirred some onion in the sauce, pepper and lard, homemade and juicy. Just like the language I lay here on the table is, you know, a little spicy. It’s the language of our people, the one you, Mother, fed me with your breast, the one my heart, Nina, gathers as you talk. In my language bridlelessly expressed, I will forever repeat and never balk: “Boy, there’s so few of us, let’s spread the love!”

|