July 31, 2022 - Twenty years a foreigner in Croatia. Part 16 of 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years - what is it like to live 12 months a year on Hvar island, for 13 years? And does it change you?

"Hvar island is so beautiful; you made a great choice. How did you come to live here?"

It is one of the most-asked questions of my life. And the answer (for those who have not already heard the story, which is well-documented) sums up the randomness of my life so far at the tender age of 53.

I have never been one to plan. My kids often wonder how I am still alive after hearing some of my travel stories of plane crashes, guns to the head, and inadvertently walking into gun battles in the West Bank. Family life has made me a lot more cautious for sure, but before family life...

A typical bout of lack of planning back in 2002 had me working as a Civil Society Coordinator in Somaliland and Puntland, the dangerous autonomous bit of Somalia where those pirates hang out.

(Somaliland was very safe, but Puntland was something else - taking the load from my 24/7 bodyguard, Arafat in Puntland in 2002)

I was based mostly in Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland, a very peaceful place, and I was sharing a house with 8 African colleagues from Kenya, Sudan, Uganda and Ethiopia. I was the only pink boy in the house. It was a fantastic experience in general, and I made some good friends. We played a lot of Scrabble, they more than me, and I would get into the habit of taking a gin and tonic to the rooftop at the end of the day and watch the world go by, an admirable self-proclaimed state which was rebuilding itself without international money or recognition.

On the evening in question, I had just got news that my house in the UK had sold, the money was in the bank, and I was free to sever all ties with Britain and buy a house somewhere in Europe. Somewhere by the sea, I decided.

My glass inexplicably empty, I ventured downstairs for a refill and a planned contemplation where I might buy my new home. I had no plans to live there full-time, for I planned to continue my aid worker career, but it would be nice to have a base, somewhere to keep my books that friends could visit.

The guys were busy with Scrabble, and CNN was on the television, the only station we could get. I was just putting the ice in the gin, when THAT advert came on.

Croatia, the Mediterranean as It Once Was.

Sure beats Croatia, Full of Life as a slogan, doesn't it?

I was hooked. The Croatian National Tourist Board's niche marketing to fat pink Brits in northern Somalia was highly targeted and effective. How ironic that 18 years later, that same fat Brit would be the only blogger/journalist sued by the national tourist board in the whole of 2020. Not once, but twice. (Read more in Diary of a Croatian Lawsuit)

A few weeks later, I found myself in Sarajevo, having a beer with a Canadian aid worker friend who had been inside Sarajevo during the siege, but managed to get to the Adriatic coast for regular R&R. She knew the Croatian coast well and suggested we decide on a destination, then visit it the following weekend with her Bosnian boyfriend to see if we could find a place for me.

It sounded like a plan and, as I didn't really know Croatia, Kendra got a pen and paper and said she would make a list of top 10 places and explain a little about each. I could then choose one, and we would head there early on Friday morning.

"Number 1 - Dubrovnik, the Pearl of the Adriatic, famous for its amazing old walled town. Number 2 - Split, home to the UNESCO World Heritage Site, Diocletian's Palace. Number 3..."

It was a balmy summer's evening, the beer was hitting the spot, and these Sarajevan ladies were smoking hot. I stopped listening, in the way one does when one asks for directions and then stops listening to the extended explanation from a passer-by. Perhaps I should live in Sarajevo instead?

"Number 10 - the island of Vis. A fascinating military island closed to the world until 1991. That's it. So which one do you like the most?"

I was so embarrassed that I had not been listening, so I closed my eyes and put my finger on the list.

(My unpronounceable new home, by Romulic and Stojcic)

Number 6 - Hvar.

"Hvar! Great choice. You do know it is an island, don't you?"

I had never heard of it (and still can't pronounce it properly).

"Of course, and it is very beautiful, isn't it?" (It must be, because it is on your list).

The story of how I bought the house will be explained in detail in the book version of this chapter (20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years: the Insider Guide to Surviving Croatia will be out by Christmas. If you would like a copy, email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Subject 20 Years Book, and I will contact you when it is published), but I want to focus on the Hvar living experience here.

Those initial weeks were blissful, and so carefree. I moved in in mid-September, fully expecting the island to be at peak season levels 12 months a year (did I mention that I never plan?). September was quieter than August, but SO refreshing. I was trying to lose weight, and I got into a daily routine of rising at 06:00, then walking along the sea to beautiful Vrboska, where I would have a morning cup of tea on the water about 06:45, then a leisurely walk home.

That walk to Vrboska is such a wonderful part of the planet - here it is many years later, filmed during the pandemic, above.

A cappuccino and cherry strudel on the main square in Jelsa after breakfast, just taking in the chilled vibe. And then a daily swim at Mina. I only learned to swim 4 years before I moved to Hvar at the tender age of 29, and doing laps from one side of Mina beach to the other was a daily task which I found very demanding but rewarding, given my terrible technique.

The afternoon was spent working on my imminent bestseller, Lebanese Nuns Don't Ski, and the evening hour was at my local, Konoba Faros, whose warm welcome and hearty Dalmatian fare had me there every night until October 1, when it was inexplicably closed.

"You are closed!" I said to the waiter, who I saw having a coffee on the pjaca the next morning. When will you reopen?"

"In May."

May!?! - that is SEVEN months away. What kind of restaurant closes for 7 months a year?

The kind of restaurant which is on an island with tourism about 4 months a year.

October was a shock.

Indeed a series of shocks. With most things now closed for the winter, life was not as much fun. And it was colder at night. I looked for the heating in the house only to find that there was none. Welcome to Dalmatia.

I didn't have many friends, and I didn't have much to do. And I didn't care that much. There was some money in the bank, and my bestseller would establish me as a world-famous writer. I accepted invitations to pick grapes and olives, a perfect entrance to the Dalmatian way of life. Be at this cafe at 07:00 and we need to leave immediately, for soon it will be too hot to pick. Dutifully I did, only to be joined by the rest of the crew an hour later. Ah, let's have a bevanda (red wine and water) before we start. And then another. And another.

The picking done, back to the konoba for grilled fish, fresh vegetables, and litres of wine in plastic bottles. Bottle empty? Simply go to the tank and refill.

My favourite recollection of this time was a boozy lunch with about 8 locals, the conversation all in Croatian. I understood every 100th word, but I was happy in the company. We had grilled sardele (sardines). I am not known for squeezing every piece of flesh from a fish off the bone over lunch (which is VERY un-Dalmatian), particularly the heads, and I left a reasonable amount on my plate, each head intact.

The chap opposite me had never even acknowledged my existence before or after, and he only ever uttered one sentence to me in his life:

"Are you eating those fish heads or what?" When I said no, he took the plate and the fish heads were gone in seconds. He never looked in my direction again.

Looking back, life was really blissful. I was a total Croatia virgin, living in a tourism bubble. I did not really appreciate it at the time, but the war had only finished 7 years before, and foreign tourists were very welcome, especially those who would spend all year. It was complete heaven, and the nature was divine.

I always wore short sleeves in winter. Trust me, when you have been brought up in a Jesuit boarding school in the north of England, then spend a winter on the edge of Siberia in temperatures of minus 32, winters in Dalmatia are mild. My t-shirts were in contrast with locals in several layers of clothing, and my first island nickname (you are not an islander if you do not have a nickname) was coined - Ludi Englez (Crazy Englishman).

Nicknames and the gruff Dalmatian way were hilarious. You could be in a meeting in a cafe and a local passing would shout LUDI ENGLEZ in your direction. It was a form of acceptance, and I appreciated the name.

'Kratki Rukavi' (short sleeves) was another phrase that was shouted at me a lot, as I walked around in my t-shirt in the 'fierce' bura wind. I absolutely LOVE the bura, and whenever it came, I would open my arms in my t-shirt and embrace it. I have never come across a more cleansing natural experience in my life. It just blows right through you and you come out cleansed on the other side.

Locals would look at me as though I was nuts. Perhaps I was. Ludi Englez indeed.

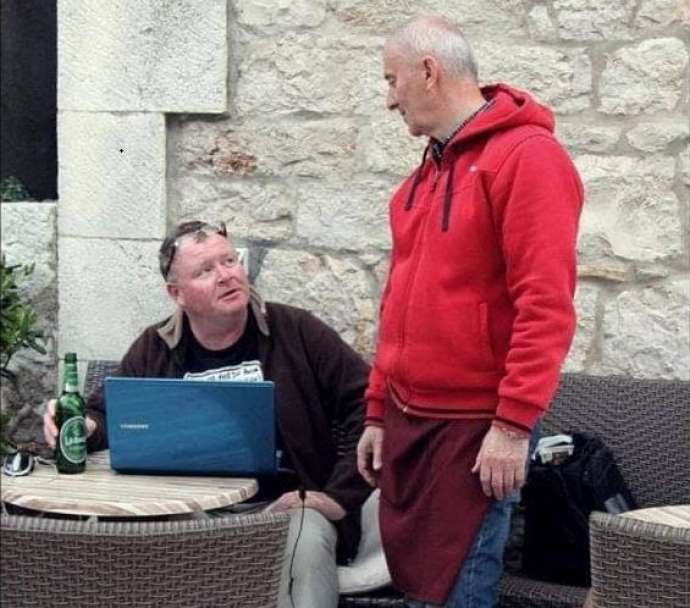

(Blogging in #ForeverKratke short sleeves in the bura - you can't beat it)

I have never been materialistic, but Dalmatia removed whatever Western trappings that remained in my body. In fact, I can't remember the last time I bought something non-essential for myself apart from alcohol (and one could argue about its necessity...). I adored the fact that Dalmatia was so non-commercial. Even though the trappings of tourism and the modern consumer society and Internet shopping are encroaching on traditional Dalmatian values, this is still a region where time - if not completely standing still anymore - is moving very slowly.

To live in a community where the Christmas tree went up on December 15 on the main square (as it did when I first moved), the first sign of the festive season (things have sadly changed), and Christmas Day comprising a present each and a great family lunch and healthy walk to Vrboska and back, was a blessing coming from a culture of commercial crap.

Local kids had nothing, but they had everything. Not so many play stations, but the Adriatic as their private swimming pool, and a safe island to run around and enjoy in idyllic nature.

One of my best friends from school contacted me after 25 years. A successful accountant with a large house near London and his own boat, he was coming to Hvar sailing and suggested we meet. It was great to see him and meet his lovely family. We exchanged life stories, me talking a little about island life, he about the pressures of the job, leaving at 06:00 Monday to Friday, getting home at 21:00, then one night out with the wife a week on Saturday, and Sunday with the kids. He could not afford to live in London, but took the train an hour a day each way. But there was the compensation of being able to sail around Hvar for a couple of weeks a year.

I smiled, and I was genuinely happy for his success, and he was clearly earning about 50 times what I was. But I wouldn't have swapped my Hvar island for anything at that point.

The fisherman and the billionaire story - from my personal experience, and I would choose the fisherman every time.

I met a girl - the assistant librarian - in the library, and she took pity on me and consented to be my girlfriend, then fiancee, then wife. I don't write about the family much as it is personal, but suffice to say that being a Dalmatinski zet (Dalmatian son-in-law) is one of life's great privileges, especially when you have a legendary punica (mother-in-law) and punac (father-in-law) as I did.

I could take at length about Hvar island and the food, the wine, the safety, the olive harvest, raising children, and doing business, but these I have already covered elsewhere in this series.

Apart from my lovely wife, there were other friends on the island, and we got into the routine of meeting for coffee (or something stronger) late morning at Caffe Splendid on Jelsa's main square, which became my office when I started our real estate business.

The core crew were Vivian, a Croatian physio of international acclaim who had lived most of her life in London, but retired to the island, and one of her many badges was as the physio for the British Olympic team in Moscow in 1980; Mark from London, who started out as a real estate client, but quickly became my best friend and got me into all kinds of trouble; and Professor Frank John Dubokovich, Guardian of the Hvar Dialects, whose success with the ladies was as impressive as it was inexplicable. The Professor and I teamed up together to start a language series on Hvar dialect that ended up being beamed into the homes of millions in the UK.

Here he is, with that iconic first video, the Dalmatian Grunt. A e!

The core team was supplemented by lots of interesting characters who had bought holiday homes through me, as well as other expats and locals that came over to join our circle. There was an Irishman who was gold prospecting in Cameroon, UN consultants, a celebrity snapper who brought Jodie Foster to Hvar as a 15-year-old, and a blogger far more famous than me who frequented my office. I always really enjoy chatting to the BBC Sport's chief football writer, Phil McNulty, and it was amazing to learn that the most popular blog of the year - his Premier League predictions for the new season - is always written at Caffe Splendid in Jelsa. Great, so I can't even achieve the status of the best blogger in a cafe in the third biggest town on Hvar Island.

Great brain food all round.

Healthcare was always great, not that I ever got really sick, but the emergency health point just outside the town was always excellent. On the one occasion we needed to get our child to hospital urgently, the helicopter from Split arrived in 12 minutes, and 12 minutes later mother and child were at Split hospital. You could not get there quicker from many parts of Split itself. Dental care was outstanding, and if you went privately, 200 kuna was the going rate for a filling.

So why, if life on Hvar island is so perfect, am I not still there?

Life on Hvar island really IS perfect, but it takes a specific mentality to live on an island I think. I often say that full-time living on a Croatian island should be given intangible UNESCO heritage status, as without those who do, tourism would not happen to the same degree of quality. And I would heartily recommend it as a way of life, especially if you have a young family. It is without doubt one of the best places to raise young children (20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years: 10. Raising Children), but it is also true that the reality of full-time living there is that locals are all busy making their money in the season, and so have little time to enjoy, and in winter, when there is time aplenty, nothing is open. Going somewhere for the weekend becomes a challenge after you have visited the low-hanging fruits of Split and surroundings, as everything starts and ends with a 2-hour ferry, of which there are only 3 a day in the off-season.

I personally MUCH prefer winter.

Although if there was no Internet...

And, as wonderful as it is for young kids, options are more limited after the age of 10 or so. Besides we were ready for a change after 13 years - there are only so many conversations you can have about olives.

Varazdin, and now Zagreb, has been a completely different experience, and I am loving the diversity and energy of city life, but always in the knowledge that my beloved Hvar island is just a few hours away. Having lived there full-time for 13 years, I now enjoy it in the same way that most Croatians do - in the summer.

Oh, and the olive harvest of course.

A new breed of foreigner is starting to discover Hvar and other Dalmatian islands - the remote worker. Just over 18 months ago, two digital nomads contacted me to rent our place, as they heard that the view and terrace were divine (they were not wrong). They ended up staying for 8 months after I helped them get the digital nomad permit. A very photogenic American couple from Silicon Valley, I thought they would make a great story on why Hvar island out of season. They agreed, some phone calls were made, and I do encourage you to watch this excellent report, which went out on primetime national TV (98% in English) on the lives of Jess and Thibaud and why they love life on a Dalmatian island in winter, above.

Are you a remote worker? This could be you...

That terrace view is pretty fab, isn't it? There are still a couple of weeks free in September (as well as 2023 of course) at Panorama Penthouse Jelsa, but hurry.

I highly recommend it. Who knows, you may end up staying 13 years...

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning - Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners will be out by Christmas. If you would like to reserve a copy, email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Subject 20 Years Book