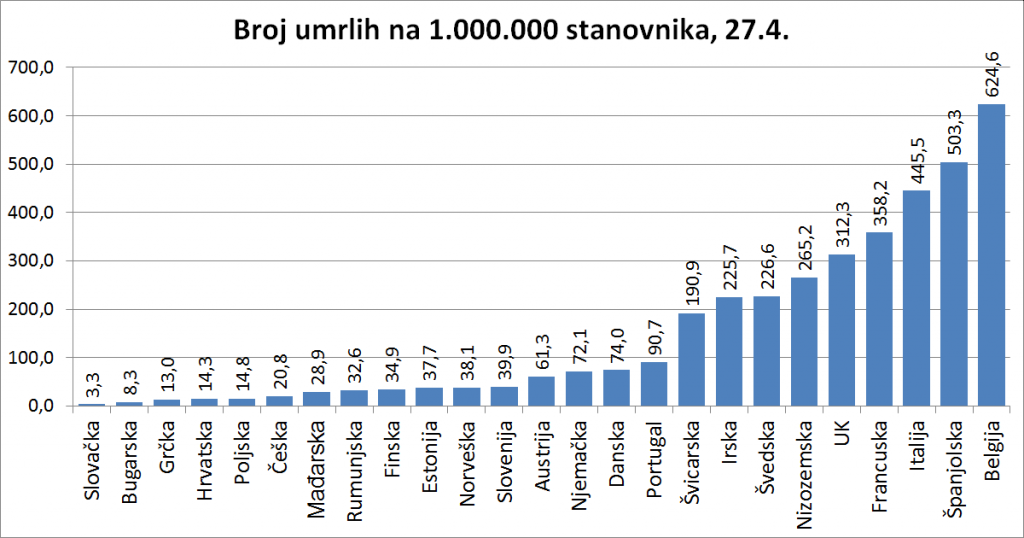

April 30, 2020 — A graph showing the number of deaths from or with the SARS-CoV-2 virus per million of the population places Croatia among the five best-ranked countries with the lowest proportional death toll, according to the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Database.

In addition to Croatia, there are Greece, Poland, Bulgaria, and - according to the available data - Slovakia. The next low-mortality group includes the Czech Republic, Hungary, Finland, Romania, Estonia, Norway, and Slovenia, with the worst situation affecting Belgium, Spain, Italy, and France. Sweden has around 16 times the death toll per million inhabitants compared to Croatia, a comparison mentioned often due to its lack of measures.

Specifying only the absolute numbers of registered infected persons or persons who died from or with the presence of COVID-19 per country does not give a true picture of the situation, given that there are huge differences in the population of individual states. In this way, for example, the terrible situation in Belgium, with its 11.5 million inhabitants in absolute numbers (7,207), has seemingly far fewer casualties than, for example, Italy with its 60,5 million inhabitants (26,977) for a long time.

It can also be said that Germany, with 6,021 deaths, has far more casualties than 2,274 in Sweden, which is not really the case at all. On the contrary, Germany with 83.5 million inhabitants is significantly more successful in fighting the epidemic so far than Sweden with 10 million inhabitants.

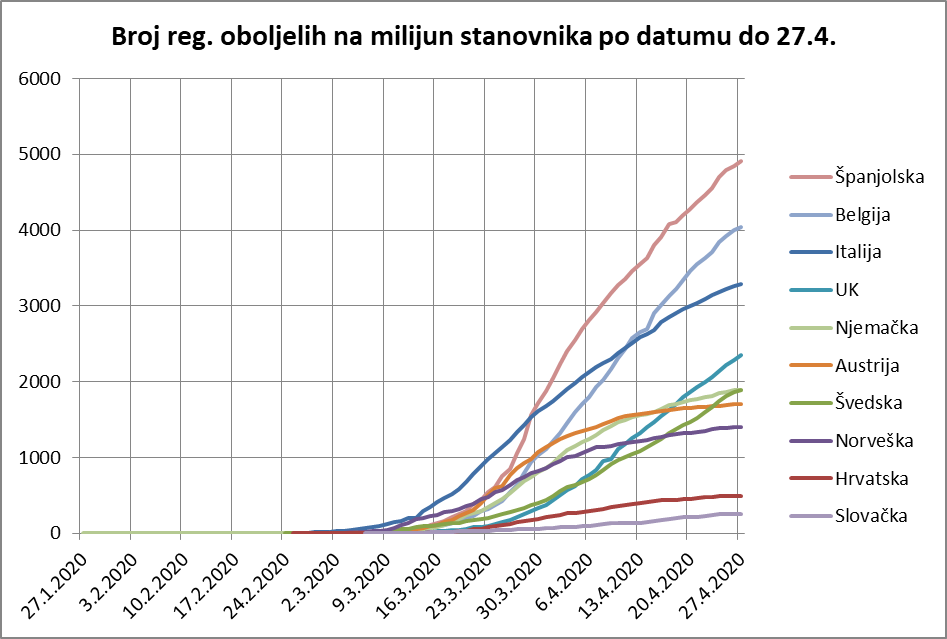

Likewise, it is difficult to compare the development of an epidemic by country in parallel if one looks at the number of registered infected persons on the same date, regardless of the outbreak of the epidemic in each country. The following figure shows the movement of the number of registered patients in several European countries on the same dates.

The graph shows a comparison of the currently registered sick per million inhabitants, but it is even more important to note the slopes of each curve in the last week or 14 days. The slope speaks to the rate of spread of the epidemic, of course, as much as there are registered patients.

We do not know the number of unregistered infected persons. It can be seen that Slovakia and Croatia have excellent control over the epidemic; that Norway, Austria, and even Germany have successfully reconciled the earlier spread of the infection, that Italy is slowing down its situation. Spain is having more difficulties, that Belgium and the UK are in a linear curve phase, and it seems that Sweden also achieved a linear curve, although it "overtook" Norway and Austria and "overtook" Germany.

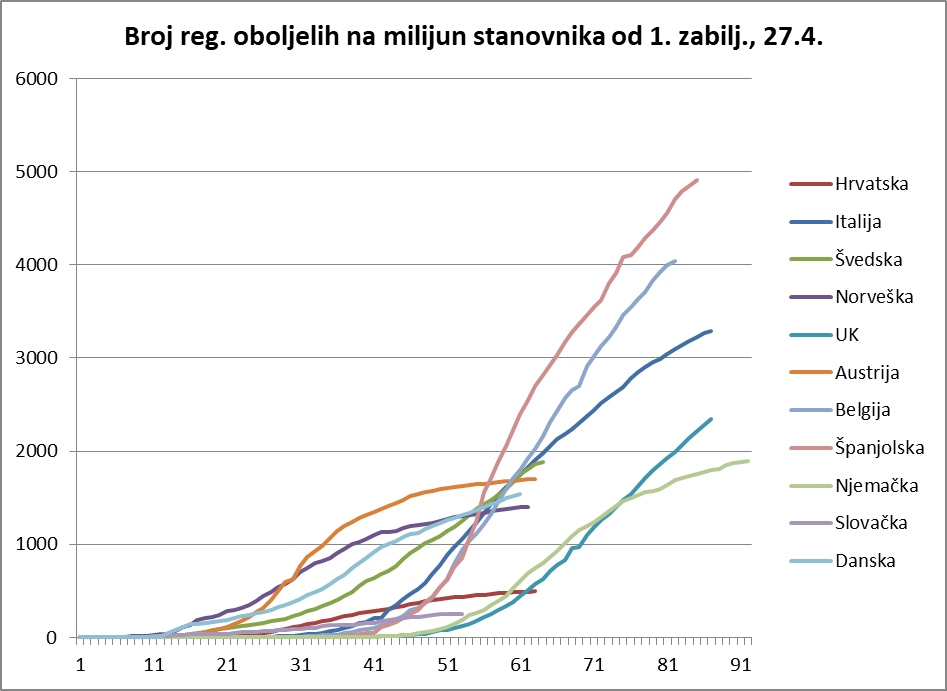

However, here we also provide an overview that begins for each country from the date the first infected person was registered. In this way, it is possible to compare the development and effects of epidemic suppression both in dynamics and in relative numbers per million inhabitants.

This chart does not show all the countries that are in the first, not only because such a view would become completely opaque, but also because of the abundance of data that needs to be monitored.

At first glance, two groups stand out. The left group is one in which the epidemic developed relatively quickly after the first registered infected person in terms of population: Austria, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Croatia, and Slovakia. Of course, these are smaller countries. The right group is one in which more time has elapsed since the first registration of the infected person, and these are countries with a larger population.

In the first group, there was a rapid increase in the number of people infected in Austria, but also a very rapid response that reversed the epidemic as early as the 32nd day, and even without "leveling", a consistent reduction in the number of new patients was immediately achieved. The epidemic has calmed down after about 50 days in that country, which of course has a great impact on deciding what to do next.

The epidemic in Norway, with an even sharper start, had a similar course, but apparently by the rapid reaction of the authorities, who reversed the trend around the 32nd day as well and achieved a calming around the 45th day.

In Denmark, the epidemic started very much like in Norway, with the first leveling off happening faster, but with more rapid growth again. Currently, the curve is linear.

The same group is followed by Sweden, which initially did not have rapid growth but, by the 55th day, has grown in the number of registered infected persons Denmark, Norway, and Austria, and there is no sign of the infection slowing.

Viewed in this chart, Croatia and Slovakia are maintaining a linear curve almost from the start of their epidemics. They maintain a very low slope linear curve and have the lowest number of registered infected persons per million inhabitants.

The group of larger countries shows that the worst situation is in Spain, which after exponential growth until the 56th day of the epidemic in its territory and then from around the 62nd day a slightly milder but still large slope with no indication that the epidemic would soon begin to subside.

It is similar in Belgium, which straightened the curve around the 54th day but has since maintained a steady but high (relative) increase in newborns with no indication of calm.

Italy, whose exponential curve started about a week before the one in Spain, reached a more moderate slope of the linear part of the curve around day 49 and shows a slight calming of the epidemic.

Germany, with some time lag compared to the first registered infected person, achieved a curve similar to Austria, with a trend reversal around day 68.

After exponential growth, the UK was able to straighten the curve around day 70, but with no indication of calm.

Looking closer to Sweden, we can see a form of exponential growth in the number of infected.

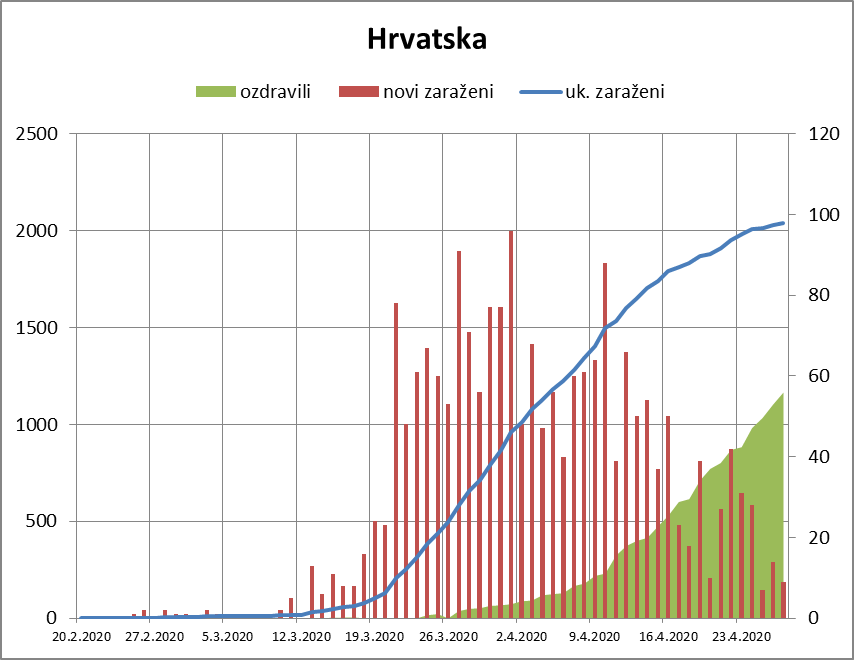

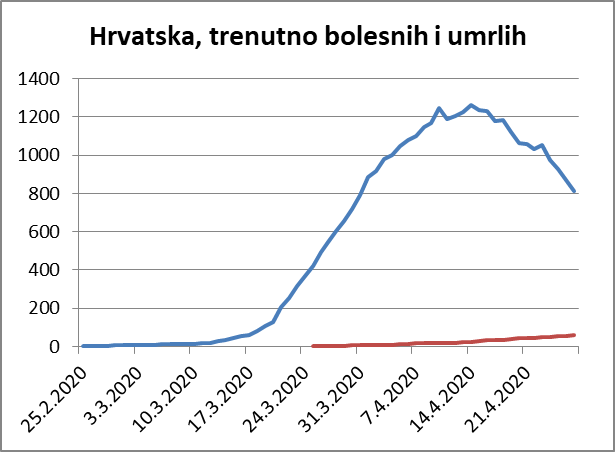

If we take a closer look at Croatia, we will see that linear growth has already been achieved around March 22 (just after the earthquake in Zagreb), that an even better slope was achieved after April 1, and that from April 16 we can speak of a calming epidemic.

Croatia's excellent result can also be seen in the chart showing the trend in the number of sick and dead.

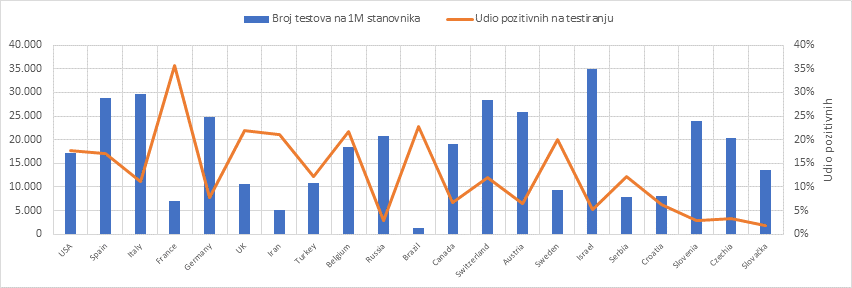

These topics often raise the question of what is a good test measure and whether we are testing enough. An excellent graphical representation of the testing ratio per million population and the percentage of positives shows who optimally tests and who does not. If you are about 10% positive you have found a good measure - Croatia is. Something ugly is coming to Brazil, only if the good weather saves them.

From everything I think it can be concluded how useful it is when policies are established on the basis of scientific knowledge and data. Scientific knowledge, in comparison to the usual political ones, is neither conservative nor radical; they are simply as they are and should be trusted. But these lessons are not exclusively health, but equally political, especially when we talk about loosening up on measures.

Of course, every state can be asked what its long-term prospect is in these new circumstances. That will not go away. Some countries, which have curbed the epidemic in the sense that they have ensured that their health care system can control the situation, maybe far more comfortable developing a further strategy than those who still have to put all their efforts into maintaining the health system's functionality.

And finally - is coronavirus more dangerous than the flu? Yes, but as far as we may know, in just a few months, we learn something new every day. The important difference is that we do not have vaccines and that the virus can mutate more often in a large number of patients.

Find more good visualizations of a pandemic at Croatia Mireo and Velebit.ai.