April 5, 2021 - Aco Momčilović, psychologist, EMBA, Owner of FutureHR, and Ph.D. Student at the University of Dubrovnik interviews Mirko Sardelić, Ph.D., Research Associate at the Department of Historical Studies HAZU, Honorary Research Fellow of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions (Europe 1100-1800) at The University of Western Australia, and formerly a visiting scholar at the universities of Cambridge, Paris (Sorbonne), Columbia, and Harvard.

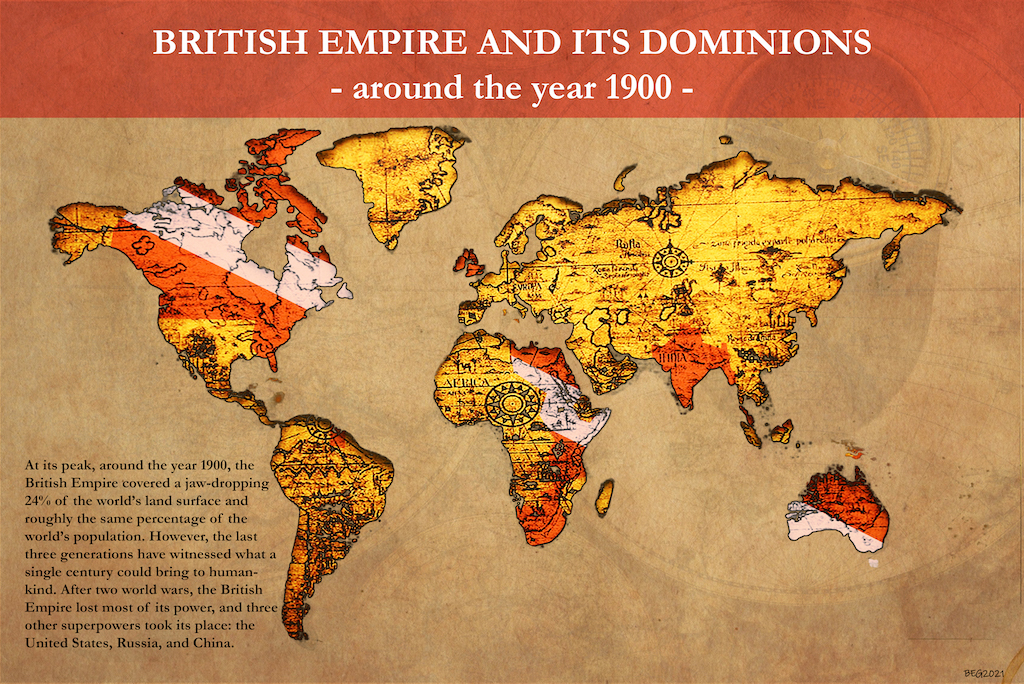

Arguably, one country could claim to have been the most successful and powerful in the world. It would be the United Kingdom, in the year 1900. No other country would ever be so dominant on a global level. There are many discussions about a post-American world, and many assume that China will overtake its dominance on the world stage. Therefore, it would be good to reflect on what was happening with state power in history.

1. What were the most powerful countries/empires at different stages of history? How was their power measured? What was the source of their power?

Mesopotamia is where the sedentary civilisation as we know it started some 10,000 years ago. The invention of the wheel, agriculture, irrigation, writing, the formation of the first cities, mathematics, and astronomy is closely connected with the area. The Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian, Babylonian empires are just some that achieved a significant level of development. The area gave birth (or was incorporated in) to some other fascinating empires in the centuries that followed. Some of them were less familiar to us in the West due to the polarisation between East and West that influenced politics and economics and how history is perceived.

We should mention the Umayyad and the Abbasid caliphates; at their peak, the latter ruled over an area larger than 10 million square kilometres, which stretched from Tunisia to Afghanistan. The Abbasid rule was considered to be the Golden Age of Islam (750-1258). The most impressive features of this empire, alongside the propulsive religion that had spread rapidly in these centuries, were a splendid commercial network, fabulous cities, and knowledge. Greek philosophy and geography, Persian, Greek, Indian mathematics, and astronomy – a whole range of sciences were developed in intellectual centres, especially in Baghdad. The empire used its networks and existing knowledge to support its development into one of the most propulsive empires. It also transferred this enriched knowledge ‘back’ to Europe that had ‘forgotten’ or had never known some of these achievements. We are talking about a wide range of things: Greek and Roman classical literature, geography, astronomy, financial tools (such as cheques and similar), and much more. When the Mongols conquered the empire’s capital, it was an end of an era and the beginning of a new one.

For a little over a century (in the 13th and 14th centuries), the Mongol steppe empire was doubtless the world's most influential force. Just imagine ruling China, the steppes, the polities along the Silk Road, Persia, the Russian principalities, and more – all in one empire stretching from the Sea of Japan to the Mediterranean. Its success lay in elements that are everything but measurable: the charisma of its founder Chinggis-khan, incredibly disciplined armies, skilful and capable generals, and a readiness to learn from the best. For example, they did not possess engineering knowledge, so they employed the best Chinese engineers to work for them; they had never run an empire. Therefore they assigned Persian administrators to important roles so that everything could function well. Any skilful artisan, artist, or trader was valued and incorporated into the Empire’s machine.

The Ottoman Empire dominated the area between Europe and Asia for four centuries. They owed their success to several contributing factors. One of them was certainly the military system: both in its structure and equipment, such as the gunpowder artillery that they brought to Europe. Another crucial factor was the Empire’s centralised structure, its ability to adapt, and its continuity – the many Turkic ethnic groups in Eurasia never formed a state but were rather dispersed across other polities. They also early took control of the majority of lucrative trade routes connecting Europe and Asia early on.

The Habsburg Empire had an enormous role in the development of continental Europe – some even say that, in some elements, it was the forerunner of the European Union. Moreover, before the House of Habsburg's division in 1556 into an Austrian and a Spanish branch, their possessions on several other continents entitled them to be considered a global empire. In Emperor Charles V Habsburg, it was given the label “the empire on which the Sun never sets” – referring to Spanish possessions in the Americas.

For roughly 300 years, the Golden Horde (a Mongol-Turkic khanate) dominated Russian lands, from the 13th to the 16th century. The next 300 years, however, saw the beginning of the Russian Empire’s rise. Ivan (IV) Grozny, the first Tzar of all Russians (1547-1584), conquered the Volga region and started both the modernisation and the expansion of the Empire. Peter the Great (1682-1725) modernised it further and made the West aware of his strength and presence on the Baltic (where he founded the splendid city named after him: St Petersburg). During his reign, the Russians had already explored the coasts of the Pacific Ocean. In his granddaughter-in-law, Catherine the Great, the first permanent Russian settlements were established in Alaska. The Russians sold Alaska to the United States in 1867 for 7.2 million dollars, retaining an empire on ‘just’ two continents.

At its peak, around the year 1900, the British Empire covered a jaw-dropping 24% of the world’s land surface and roughly the same percentage of the world’s population. However, the last three generations have witnessed what a single century could bring to humankind. After two world wars, the British Empire lost most of its power, and three other superpowers took its place: the United States, Russia, and China.

While the former two are, relatively speaking, more recent entities, China has had impressive continuity of civilisation. It is a pity that some aspects of Chinese history are not taught in this part of Europe; I am sure the comparative material could offer interesting food for thought. I remember that some ten years ago, Professor Walter Scheidel of Stanford University had an interesting project that compared the Han Dynasty (202 BC-AD 220) to the Roman (Republic and) Empire, which prospered during the same period. It discussed the convergence and divergence of two powerful empires on opposite parts of Eurasia, taking into account economic and military power and state institutions.

2. Was the world ever before polarised as in the period of the Cold War? Who were the competing forces?

This polarisation you talk about is a classic mental game of Us and Them (or rather: Us vs. Them). The first example that comes to my Eurocentric mind – even though I have tried a lot to expand my horizons since, still my education was such – was the division made by the ancient Greeks. They were arguably the most responsible for the dichotomy between Asia and Europe – two enormous and fabulous constructs that influenced so many generations’ perception of everything from geography to social relations.

And indeed, it was a huge clash because the Greeks were in the orbit of one of the most powerful empires the world had ever known: the Persian Empire. Founded by Cyrus the Great (c. 600-530 BC) for a little over two centuries, it ruled the vast fertile landmass from the Indus River to the west coasts of the Black Sea and Egypt, covering more than five million square kilometres. (In comparison, the EU covers less than 4.5 million km2.)

There was a crucial reason why ‘Europe’ feared the East. After the Persians, in the millennium after Christ, several waves of nomadic migrations (which are usually dubbed ‘invasions’ by historians) occurred, which substantially affected state formation in Central and East Europe, to begin with. There were Huns, Avars, Magyars, and Cumans, all-powerful nomadic forces of nature. It all culminated with the Ottoman Empire: exactly at the geographical border of Europe and Asia, but significantly different enough to be a powerful Other for several centuries in the Early modern period (15th-19th centuries). As this empire declined, the Russian Empire became a superpower in the East, as we mentioned earlier.

In ancient times, Alexander III of Macedon was a famous king known as Alexander the Great (356-323 BC). In his early thirties, he ruled an empire stretching from the Mediterranean to the Indus river, an area larger than five million square kilometres. (Just for comparison: the legendary Roman Empire was 4.4 million km2 at its peak – and it took the Romans several centuries to accomplish what Alexander did in a bit over a decade.) His conquests were not just spectacular military and logistic achievements; they were remembered for centuries for something else, although it was related to his military victories. He went east and conquered Asian nations, one by one, creating a long-standing myth that was frequently rehearsed, especially during so many centuries of military domination by Eurasian nomads. His status was probably somewhere between that of a superhero and a saint-protector from the dangerous races of the East: such as, for example, Gog and Magog, whom he ‘repelled’ by constructing an enormous iron gate in the Caucasus.

3. According to Joseph Nye, there are several types of power. Who had the strongest military power? Was a country/empire able to influence others with their economic power? And is soft/smart power (the ability to attract and co-opt rather than coerce) something that has been gaining importance only in recent centuries?

Joseph Nye’s famous concept of ‘soft power’ is quite interesting and popular but is certainly not entirely original in its principle. Old Chinese traditions, such as Lao Tzu’s teaching, argue that water, fluid and soft, will eventually overcome the rock, rigid and strong. This was immortalised in the saying, ‘What is soft is strong.’ However, while this might be true for long-lasting concepts and processes, it certainly evades the grasp of the modern human, increasingly impatient, trapped by tight schedules, bombarded with information, lured by temptations of all sorts.

In terms of manpower, the strongest military has been reserved (quite expectedly) for the Chinese for millennia. The Russians used their manpower quite successfully (along with their winter) in the Napoleonic and World Wars. The aforementioned Mongols used skill, discipline, and strategy – some even say that it was the Mongols who invented the operational art of war, which is, according to others, a much more recent (19th-century) invention. As we mentioned previously, the Mongols attracted some merchant elites, providing a huge intercontinental market and offering trading benefits.

The Mongol cavalry is also an example of how skill, organisation, and discipline can compensate for numbers. There are more than a few examples, such as the Spartan and Macedonian phalanx, the Roman legion, English bowmen, and others.

Nonetheless, trained units and the technology they are equipped with come and go, while certain cultural imaginaries remain for centuries and millennia. And there were so many examples in which the conquering elites chose to blend into existing cultural frameworks rather than promote their own. This is the soft power you refer to, the sophisticated, intricate fibre of a civilisation’s reach and legacy. The Romans adopted many threads from the Greeks, Etruscans, Celts, Egyptians, Persians, and others. As we said, Greco-Roman and Christian foundations are embedded in the very core of the European idea and civilisation. This is exactly why there was a Holy Roman Empire in the Middle Ages as well, and why new imperial capitals all aspired to become ‘the new Rome.’

Soft power came embodied in various shapes, such as literacy, identity, literature, legal and economic institutions, and so on. The elements developed by religions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, or Islam have also been crucial in shaping the values of a larger part of the world’s population. Apart from these, I have also been much impressed with some Australian, American, and African native cultures’ attitudes towards the environment and the beings we share it with: they were the true guardians (not owners) of the land they lived on.

This century has seen the combined use of both types of power: smart and (more or less) sophisticated soft power and hard power behind the scenes, whose scary shadows appear to remind us of the fact that superpowers have an ever-more-efficient military arsenal no one should be so reckless as to provoke.

4. Those who are studying economics on the world level are not surprised by the rise of the West in the last century, but in the broader scope of time, in China, this was perceived as a short-term fluctuation. What were the longest periods of domination by a particular entity?

The West had its 500 years of world dominance, from the Age of Discoveries to the 21st century. Portugal and Spain were the first to begin expanding, and the English, French, and Dutch followed. The Atlantic sea empires used the conjuncture and took the best from a world that was still huge, remote, and full of wonderful riches – there to be taken by those who had skill and military power. The United States used the momentum it had gained during its expansion in the 19th century and became a superpower in the 20th century. Over the last several thousand years, China has been a ‘dormant’ giant: in retrospect, one can acknowledge its superiority in its population and civilization level.

However, in today's global world, China has become a true global superpower within just a few decades. In the late 1990s, China’s imports and exports made up a bit over 3% of global trade. Within 20 years, in 2018, it rose to a staggering 12%, leaving the US in second place, with 11.5% of global trade. Not only that but, as Willy Shih, a professor at Harvard Business School, has recently summed up: “The world is dependent on China for manufacturing.”

In ancient times, one of the most impressive and long-lasting civilisations was Egypt. When King Menes united Upper and Lower Egypt, around 3100 BC, till the conquest of Alexander the Great (in the 320s BC), the country was one of the most dominant and most fascinating human cultures. Apart from the fabulous architecture and engineering, Egypt's legacy includes amazing achievements in medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and other sciences. The calendar we use is related to the one they used, while the paper we read from has its ancestor in papyrus leaves from the Nile basin.

5. What influences on our everyday lives today have roots in ancient civilisations? What technological, artistic, or scientific discoveries shaped our way of life?

I like the quote that goes something like: “History is about choosing our ancestors.” This means that we have 2x4x8x16… male and female members in our ancestral line, but we always ‘prefer’ some over others. And by this, I mean their (perceived) influence on our own identity. The world has seen so many different types of societies, governing models, (con)federations, intercontinental empires, and small yet successful city-states such as Athens, Florence, Dubrovnik, or Singapore. They have all used some advantages, such as geography, political structure, or trading skills, to extract the maximum from the circumstances in their space-time framework. Also, their leaders were considerate enough to choose their ‘ancestors’ – i.e., the role models they shaped their present and future upon.

There are many things in our lives that we cannot choose, and many that have been chosen for us. Let’s say we have some 30.000 US$ set aside and we want to buy ourselves a nice electric car. I mean, they have indeed increasingly developed into something desirable over the last couple of decades. However, it took them a while to get a chance on the market because gasoline cars were invented much earlier, right? Wrong. Both were produced in the 1880s, but the gasoline version was preferable for one reason or another.

During my freshman year at university, I read a few novels by Graham Greene (thank you, Raymond). In one of these (in The Third Man, I’d say) – and it still resonates in my memory – one of the characters ‘argues’:

“In Italy, for 30 years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had 500 years of democracy and peace - and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.”

What does this say about the circumstances of development? True, wars and conflicts generated innumerable precious inventions: the will to survive generates spectacular ideas. However, does this mean that the Swiss today desperately miss something the Italians have? In terms of their quality of life, of course, not in terms of Italy’s sandy Mediterranean beaches or the number of UNESCO cultural monuments, which I am sure most Swiss citizens can regularly visit, in their (electric) cars even, within just a few hours.

From the 21st century point of view, it is easy to neglect the impact geography had on the historic balance of power. For most of its history, Europe was, in the words of Andre Gunder Frank, “a distant marginal peninsula” of Eurasia. You should also remember that the most important world empires were exclusively positioned in the northern hemisphere, within those ‘lucky latitudes’ that supported agriculture and other conditions crucial for social and political upgrades.

Only after the living conditions had been acquired that the transfer of knowledge, discoveries, and other factors began shaping societies in the way we read in history books. It may sound complex, but the further you go back in history, and the more you expand the holistic picture, covering a range of aspects such as geography, technology, and political and economic thought, the more accurate you become in reconstructing the causes for the ‘rise and fall’ of some concepts. Moreover, you discover they do not move in these two dimensions (up and down), but rather most of them circulate, returning to the stage in improved, adapted models, according to the challenges of the time.

Part 1: https://acomomcilovic.medium.com/history-of-power-part-1-e10e57f7b29c

For more, follow our politics section.