Fjaka: A State of Mind that Comes Alive During Croatian Summertime

July 1, 2022 - “A sublime state in which a human aspires for nothing” may seem like a luxury afforded by the privileged, but Croatians in Dalmatia wholeheartedly conclude that the pleasure derived from il dolce far niente – famously known from the ‘Eat Pray Love’ book-to-film adaptation – can be found everywhere from remote farms and vineyards to crowded touristic sites! A look at 'fjaka' in Croatia.

Photo: Romulic & Stojcic

Fjaka is known to be embraced by many during the appearance of the great summer heat, as the mind, soul, and body slow down exceptionally during the oppressive temperatures. Therefore, the Mediterranean sun is known to have brought the term “fjaka” to life – marking the renowned origin of Croatia's national and cultural heritage.

Split, the largest and most beloved city in Dalmatia, is known to be the hub for fjaka and the amount of energy it saps away from the body. Situated on a peninsula in the Adriatic Sea, the vibrant port city is home to many phrases, one of them being “Ajme, judi, ufatila me fjaka!” (“Alas, my friends, jaka has caught me!”). And although many appreciate this state of mind, others may not feel so open to it.

Photo: Romulic & Stojcic

In comparison to the lifestyle seen in metropolitan areas, which is driven by busy schedules and the uncomfortable feeling of unproductive afternoons spent basking in the sun, the culture that is ingrained in the Croatian psyche can be viewed as ‘lazy’. However, it should be argued that it is quite the opposite! The philosophy that is adopted by Croats allows them to know how to enjoy themselves and ultimately not get burnt out from the regular, strenuous working days that many of us face.

While naturally, it is impossible to be doing Fjaka all the time, we should all consider allowing it to wash over us like the peaceful Mediterranean breeze once in a while. Grow to appreciate the slower Dalmatian pace and the relaxed attitude to taking things one day at a time!

For more, check out our lifestyle section.

Three Reasons to Visit the Croatian Adriatic Coast in September

June 26, 2022 - Summer has just arrived and in what could be called the first year back to normal since the pandemic began, and the country is preparing for a big wave of tourism in the next two months. But have you thought about September as the ideal time to visit the Croatian Adriatic coast? Here are three reasons you should.

Ferries everywhere, parties along the coast, film and music festivals, Instagrammable landscapes, and much more. There is no better time to visit the Croatian Adriatic coast than in the height of summer... or is there?

It is not a secret that many seek to anticipate the high season, or wait a bit for it to pass. Before the pandemic began, months like May, June, September, or October attracted many tourists from abroad and there was no shortage of flights arriving at Croatian airports. Unfortunately, the situation in recent years has forced many to focus their efforts on July and August, due to the uncertainty caused by travel restrictions in Europe.

However, it is almost impossible to deny that the situation seems to have finally reversed. After two difficult years, travel restrictions to Croatia are almost non-existent. Although the current Russian invasion of Ukraine has also generated a great deal of uncertainty for companies linked to tourism, as well as for tourists themselves, the Ukrainian resistance and the progressive retreat of the Russian invasion seem to offer a more positive outlook.

If you don't feel like visiting the Croatian Adriatic coast in the high season or you're still not sure when to book your tickets and accommodation, here are three reasons why you should consider September as a good month to travel to Croatia.

Fewer crowds

It is not an accident, nor a miscalculation. Not a single space to lie on the beach, you have to wait to walk through the narrow streets in the old towns, no tables available at restaurants, sold-out tickets for ferries... July and August are crowded months all over the Croatian Adriatic coast, and for many, this is not very pleasant. In September, however, you will notice how the beaches begin to empty and the number of tourists in the coastal cities and on the islands begins to decline week after week.

Many returning to work, young people preparing to go back to university, and the little ones are back at school... the holidays are over! And this is where yours begin, without crowds.

Photo: Mario Romulić

Hot, but not too hot

By the time this article was written, weather forecasts anticipate temperatures above 33 degrees for the last week of June. Although there is a heat wave that will hit much of the region, temperatures between July and August on the coast average between 29 and 32 degrees, and do not drop below 24 degrees at night. This may not be so bad for some, such as those who come from cold or sea-less countries, as they can take full advantage of the freshness of the Adriatic Sea.

However, there are others who can feel really hit by the strong heat, and it is totally valid to avoid places with very high temperatures, as it can be even dangerous. In September, the weather is still very pleasant to take a dip in the sea and there is even no need to bundle up at night, because during the day the maximum temperature averages between 25 and 26 degrees, while at night it can drop to 18 degrees. And not only is it good to go to the beach without fear of burning, but September is also a good month to visit the National Parks without a crushing sun to stop you.

Photo: Mario Romulić

Budget-friendly

Perhaps the first two can be reasons that one can anticipate, but when it comes to prices between July and August, things can be very unnerving. Landlords raising their prices at the last minute, taxi drivers charging fortunes from here to there, or tickets to certain places of interest at an exorbitant cost, visiting Croatia in the high season can give one goosebumps when it's time to do the maths. Some say it's fair, others say it's scandalous, but the truth is that many will raise their eyebrows after seeing the prices of accommodation, ferry tickets, or the taxi meter.

You can already see the prices in September, and the difference is noticeable almost immediately. While they are not as low as in April or October, when you consider that there will be fewer crowds and the weather will still be spectacular, prices in September are surely a bargain.

Photo: Mario Romulić

For more on travel in Croatia, follow TCN's dedicated page.

Zadar: Much More than Your Typical Dalmatian Town

June 21, 2022 - Is Zadar one of the most underrated cities and regions in Croatia? Like many other cities and towns along the Adriatic coast, you tend to think that you have seen everything in two or three days. Think twice.

Facebook is a wonderful world where you can go from being a tourist to a travel guide without any education. You go from asking for recommendations to becoming an authorized voice in the tourism field. It wouldn't bother me if it were the case of people discovering the magic of a little-known and little-explored place, highlighting what a place has to offer that perhaps others were unaware of. But I find it interesting when a user (whose identity I will keep anonymous) says in a Facebook group that Zadar is a destination to stay for no more than 2 days.

I'll pretend I didn't read that, and instead try to answer this other user as concisely as I can:

Unfortunately, many Croatian cities are stereotyped and reduced to one or two points of interest. Dubrovnik is its walls and the filming location of Game of Thrones. Split is Diocletian's Palace. Pula is the Roman amphitheater. While none of this is bad, it is true that for many people who stick to their travel itineraries they can come in and say they've seen it all. I don't mean to change their mindset, but although word of mouth can be beneficial, it can also be dangerous if the ''first mouth'' isn't exactly right.

I can say now I've been on both sides. Almost exactly two years ago, my parents were visiting me in Rijeka, where I had just finished my semester of studies. The plan was to give me a lift to our home in Split, and we rented a car in Rijeka. Although it is possible to make the trip to Split on the same day, we decided that we would sleep one night on the way. We chose Zadar. The apartment we rented was in the very heart of Zadar's old town, and we were at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. It was a very minimalist trip, and we barely got to know some of the main points of interest around the old town: the sea organ, the Greeting to the Sun, the Roman forum, the church of St. Donatus, and I think that was it.

I wish I could say that the pandemic was a legitimate justification for not exploring more (the infamous tennis tournament organized by Novak Djoković was taking place at that time), but I'm sure that at some point before we resumed the trip to Split we said: ''Ok. We've seen it all''.

Fate brought me back to Zadar two years later, and how wrong I was. I hadn't seen anything.

I have to mention that what you probably already know about Zadar is definitely worth discovering. Watching a sunset from the sea organ and the Greetings to the Sun is not something to be underestimated under any circumstances. In the same way, the history that accompanies the old town through its churches, the Roman forum, the convents, and the city gates deserve all your attention, since we are talking about one of the most important cities in Croatia in terms of history.

If you're not sure what else is there to see, it doesn't hurt to go to a tourist office or ask a local for recommendations. It's different when the person giving you recommendations on places to see or things to do was actually born there. It's already personal. In most cases, they will want to leave a great impression of their hometown and also recommend things that one would not usually see. You must also remember that Croatia is not a country with isolated cities, but that it stands out a lot for its regions as a whole. Administratively speaking, yes, it is true that some cities are better positioned such as Pula, Rijeka, Zadar, Sibenik, Split, or Dubrovnik. But you would be surprised if you knew how much you can find beyond the Roman ruins and beaches in these cities.

Zadar is its Sea Organ, its Roman Forum, the Greetings to the Sun, the Church of St. Donatus, its Franciscan Monastery, and its Old Town.

But Zadar is also the historical city of Nin and its healing mud beaches. (Image: Nin Tourist Board)

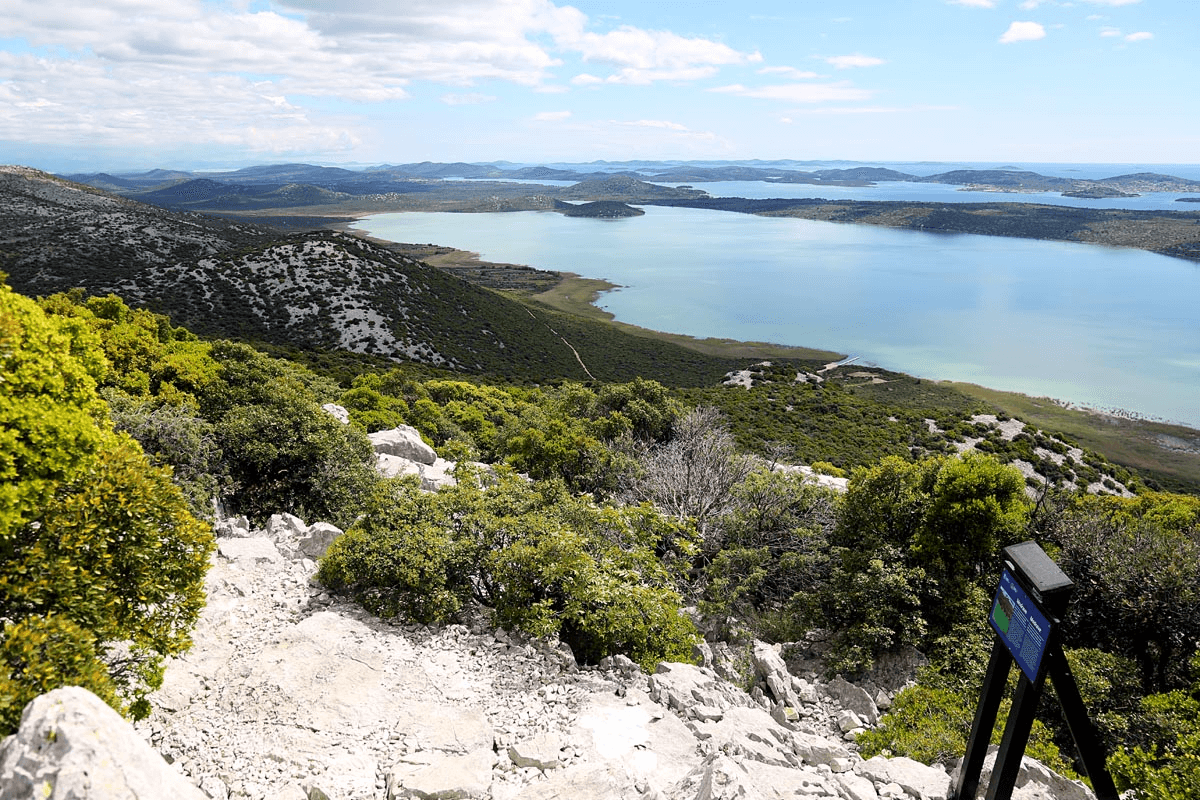

Zadar is the largest lake in Croatia, the Vrana, and its surroundings. (Image: Pakoštane Tourist Board)

Zadar is the royal city of Biograd na Moru. (Image: Biograd na Moru Tourist Board)

Zadar is the Ottoman residence of Maškovića Han. (Image: maskovicahan.hr)

Zadar is the jawdropping views from Vidikovac Kamenjak. (Photo: Jose Alfonso Cussianovich)

Zadar is sailing through the archipelagos of Kornati and Telašćica. (Photo: Mario Romulic)

Zadar is reconnecting with the nature of Paklenica. (Photo: Jose Alfonso Cussianovich)

Zadar is hiking in North Velebit National Park. (Image: North Velebit NP)

Zadar is tasting internationally recognized wines like those from Fiolić Winery. (Photo: Jose Alfonso Cussianovich)

Zadar is trying the famous Pag cheese. (Image: Pag Tourist Board)

Zadar is all that, and much more. In the end, I think the lesson is to dare to look for something different than what we usually see in pamphlets, on TripAdvisor, or in the comments section of a Facebook group.

For more on travel in Croatia, follow TCN's dedicated page.

€6.36m for Reconstruction of Dalmatian Ports

21 March 2022 - Minister of the Sea, Transport and Infrastructure Oleg Butković presented 45 contracts for port construction and reconstruction in Zadar, Šibenik-Knin, Split-Dalmatia and Dubrovnik-Neretva counties at a ceremony in Zadar's Gaženica Port on Monday.

The contracts, worth HRK 47.7 million (€6.36m) in total, will finance the construction and reconstruction of ports open to public transport, the modernisation and construction of fishing infrastructure, and the repair and reconstruction of the maritime domain in general use.

"This is the continuation of the large investment cycle for ports and seafronts. We are a country that lives off the sea and is oriented towards the sea, so it's good that a large chunk of the HRK 25 billion of investment in the transport sector goes towards the reconstruction of ports, seafronts and piers," Butković said after the ceremony.

He said that total investment in ports and port infrastructure along the Adriatic amounted to about HRK 2 billion.

Before the ceremony, Butković had visited an extended ferry pier in Tkon on Pašman island, which was formally opened today. The new ferry port is the first of 28 port infrastructure upgrade projects in Croatia financed with EU grants. The total value of the project is HRK 32.6 million, of which HRK 27.7 million came from the EU Cohesion Fund.

Tkon is the ninth busiest ferry port in Croatia in terms of the number of passengers (500,000 annually) and the 11th busiest in terms of the number of vehicles transported (120,000). It is the second busiest port in Zadar County.

(€1 = HRK 7.5)

Croatian Traditional Jewellery: Coral, Silver and Gold in Dalmatia

February 26th, 2022 - Following our feature dedicated to traditional jewellery of Istria, a look at the intricate filigree pieces traditionally worn in Dalmatia

In the first part of this series, we wrote about medieval jewellery discovered in Istria that has only recently seen a revival in the form of artisan replicas.

The traditional jewellery of Dalmatia, however, has historically been an integral part of folk costumes all over the region, and has been worn and treasured by generations of women up to the present day.

Let's take a look at some of the most prominent designs found in Dalmatia:

Pag beaded necklace and earrings / Paški peružini i ročini

First, a quick disclaimer: depending on who you ask, Pag island is a part of Kvarner, Dalmatia, neither, or both. We'll leave the people of Pag to define their cultural identity as they see fit, and will include the island in this particular feature based on the shared traits of traditional jewellery of Pag and that found in the rest of Dalmatia.

The traditional costume of Pag island largely owes its distinctive appearance to the triangular headdress worn by women, made of starched white linen and lined with intricate lace.

The Pag lace is a showstopper, but if you take a closer look, you’ll see that the ladies are also adorned in jewellery when clad in traditional garb. It’s been worn on Pag since the 16th century, and considering that there were no master goldsmiths living on the island at the time, the jewellery was imported from Venice.

Pag folk costume / Image by Hotel Biser

Pag folk costume / Image by Hotel Biser

There are two distinct types of jewellery worn as part of the Pag folk costume. Delicate beads made in the filigree technique are called peružin; string a number of them together and you get a gorgeous necklace. Decorative hair pins featuring a single peružin were used to help keep the headdress in place, as seen on the above photo. It should be mentioned that the traditional peružini were once made to weigh exactly 123 grams each!

A modern replica of Pag peružini / Image by Zlatarnica Jozef Gjoni

A modern replica of Pag peružini / Image by Zlatarnica Jozef Gjoni

The other distinctive piece found on Pag are the ročini, dangly bell-shaped earrings typically made of silver or gold.

A modern replica of Pag ročini / Image by Zlatarnica Jozef Gjoni

A modern replica of Pag ročini / Image by Zlatarnica Jozef Gjoni

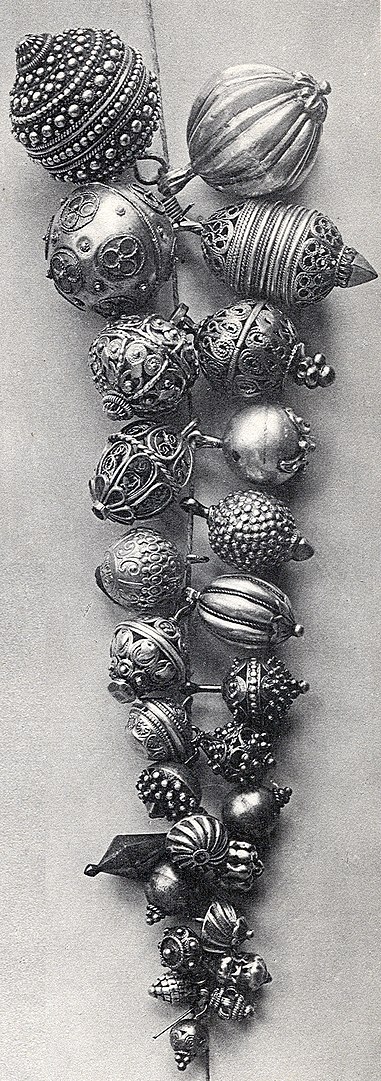

Šibenik button / Šibenski botun

Arguably the most popular piece on this list, the intricate Šibenik button used to be a decorative part of men’s folk costumes. These days, it’s one of the most recognisable symbols of Šibenik that doubles as an authentic souvenir. And while the motif is still seen in men’s accessories - tie clips, cufflinks - it’s not exclusive to gents anymore and is featured in women’s jewellery as well.

Similar to the Pag peružin, the Šibenik button is a hollow filigree bead composed of two half-spheres bonded together. Traditionally, the button used to be made of silver, but nowadays you’ll also find modern replicas made of gold, rose gold and aluminum. It's also called puce and toka, and was known to come in different sizes and designs depending on intended use.

Various versions of Šibenik buttons

Various versions of Šibenik buttons

Even though there are metal buttons discovered in Dalmatia that date back to ancient times, the famous decorative bead only became widely adopted as a part of traditional garb around the 17th century.

As mentioned, they were only worn by men back then and were an indicator of social status and rank. The buttons were essentially comparable to military medals, as they were awarded to heroes and commanding officers from the region by Venetian generals based in Zadar.

Over time, the Šibenik button became so popular that a large number of artisans, from northern Dalmatia all the way to Albania in the south, specialised in the filigree technique so that they could create the intricate orbs.

Šibenik button earrings / Image by Zlatarnice Rodić Facebook

Zlarin coral / Zlarinski koralji

For a little intermezzo on our filigree-laden tour, we’re heading to Zlarin island right off the coast of Šibenik, historically known for quite a specific thing: coral.

People of Zlarin have dealt in coral harvesting and processing since the 14th century; while harvesting isn’t that common anymore, Zlarin is still home to a handful of skilled artisans creating unique coral jewellery.

Red coral necklace / Šibenik Tourist Board

Red coral necklace / Šibenik Tourist Board

Red coral, also called precious coral, thrives in clean waters and grows at the depth of 30 to 200 metres. In its natural state, it’s covered in a crust that needs to be filed down for its intense red colour to show; the skeleton is then cut into smaller pieces, each of which gets filed, shaped and polished. Polishing is the most crucial stage, a process that can last up to a few days and results in a high shine. The colour has a range of 10-15 hues, varying from a light to a deep red.

The art of coral harvesting was a skill passed from father to son. Coral was historically harvested by trawling, using a tool called inženj, a wooden cross weighed down with a heavy stone and fitted with fishing nets. Coral would get entangled in the nets as they dragged across the seabed and break off when the nets were pulled out of the sea.

Fishermen from Zlarin participated in harvesting expeditions all over the Adriatic - sometimes straying even further, as far as Greece - and sold the catch on Sicily.

Red coral / Zlarin Tourist Board

Red coral / Zlarin Tourist Board

After the fall of the Venetian Republic that controlled the coral trade in the Adriatic, the people of Zlarin were granted the exclusive right to coral fishery. Like elsewhere in the Mediterranean, coral was overharvested due to its value until it was nearly eradicated, and so the practice gradually became less common by the mid-20th century.

Nowadays, the island is home to two coral shops run by jewellery makers that keep the tradition alive. Zlarin is also about to get a Croatian Coral Centre, a state-of-the-art facility dedicated to the island’s history of coral harvesting that's set to open sometime soon.

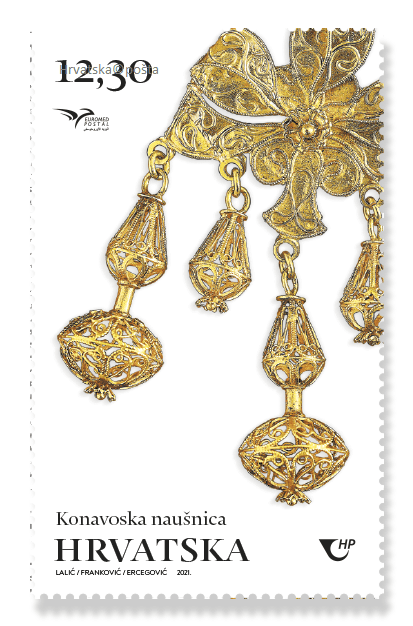

Konavle earrings / Konavoske verižice & fjočice

We’re heading further south, to the Konavle area near Dubrovnik, the home of the elegant Konavle earrings.

The verižice hoop earrings from Konavle have a small pendant, typically a pearl or a coral bead. In the olden days, there was a social order to wearing jewellery in Konavle: young girls wore smaller earrings, and the older the women got, the bigger earrings they could wear. Young men were known to present their brides with the lovely hoops as a gift before their wedding day.

Modern replica of Konavle earrings / Image by Zlatarnice Rodic Facebook

Modern replica of Konavle earrings / Image by Zlatarnice Rodic Facebook

Traditional jewellery was handled with care and kept in decorative wooden boxes or in special compartments in chests. The best pieces were only worn in rare special occasions, as jewellery was considered a family heirloom and was passed down from generation to generation.

Another type of earrings popular in Konavle are the so-called fjočice. Worn by brides on the day of their wedding and in the first year of marriage, the dangly earrings had several pendants made in gold filigree.

The Croatian Post paid homage to the lovely fjočice with their own postage stamp, created by designer Alenka Lalić from Zagreb:

Interestingly, the Konavle earrings weren’t actually made in the Konavle area, but were instead manufactured by goldsmiths in Dubrovnik. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the goldsmith workshops predominantly focused on traditional jewellery, driven by the increasing demand from Konavle and the wider Dubrovnik area.

Dubrovnik necklace / Dubrovačke peružine & kolarin

As Dubrovnik used to be a major goldsmithry centre from the medieval times to the mid-20th century, it doesn’t come as a surprise that the Pearl of the Adriatic has its own type of traditional jewellery.

You’ll surely recognise the peružin motif by now, the hollow filigree beads which in Dubrovnik were traditionally made of gold. Strung together, the beads make a lavish necklace called kolarin.

The kolarin were most commonly composed of 12, 14, 16 or 18 peružin beads, either simply strung on a silk ribbon, or connected with small golden links, pearls or coral beads. They were known to feature a heart-shaped pendant or a golden cross, altogether making a show-stopping piece typically worn on special occasions.

Nowadays, you'll most commonly find earrings or pendants featuring the Dubrovnik peružin bead.

The Mysterious Origins of the Dalmatian Dog

February 19, 2022 - Is the Dalmatian dog actually from Dalmatia? Inside the history of the spotted black-and-white creature.

We’re all familiar with the unique breed that is the Dalmatian dog, whether it's thanks to a certain popular Disney film, or the countless fabric designs inspired by that distinctive polka-dot pattern. Based on its name, one would believe that the dog originates from the Dalmatian coast. And for Croatians, this would be an honour to have such a beloved dog breed associated with our country.

But actually, their supposed origins trace as far back to Ancient Egypt. King Cheops, who built the Great Pyramid, was said to have owned one in 3700 BC. Greek frescos from 2,000 years later were seen to depict black- and brown-spotted dogs. From both of these ancient sources, some canine historians point the origins of the Dalmatian to ancient breeding between a Cretan hound (originating from the Greek Island), and a White Antelope dog, resulting in a swift, white dog that hunted deer and ran with horses. In fact, the breed’s name is said to be a version of “Damachien”, a name that blends the Latin term for fallow deer (“dama”) and the French word for dog (“chien”). While some say it is an Egyptian breed, others associate it with being French, Scandinavian, or Italian. Confusing, right?

Adding to the mystery, the Dalmatian was first determined as a breed in England, as they were brought there from Europe with the purpose of being used as a carriage dog - thanks to their agile and athletic appearance, their natural strength, and their affinity for horses. They were also used as guard dogs, running alongside carriages to serve as protectors, and in the military to attack mounted units, in which they were respected for their battle efficiency.

These dogs were also a favourite companion of firefighters. Running alongside the horses that pulled their water pumps, they acted like living sirens, barking ahead of the firemen approaching the site, ensuring bystanders kept out of the way. In the United States, the use of Dalmatians in the fire department was especially popular. Even after the horses were soon replaced by shiny red engines, the dogs continued to have a place of honour in the firehouse.

And, in the spirit of the breed’s playful nature, Dalmatians were circus dogs. Their ability to perform tricks and amuse the audience is owed to their retentive memory, which paired with their natural charisma and distinctive appearance made them natural performers and a hit with the audience. Dalmatians are known for their seemingly endless energy, which may have them appear as goofy as the golden retriever, or similar family dog breeds. But on the contrary, they are quite smart which paired with their strong memory is super helpful when it comes to training.

But the appearance that made them most popular was 101 Dalmatians, the beloved Disney film which helped portray them as a loveable companion and a family dog, which led to a sudden rise of families getting the breed. Loyal and good with children, Dalmatians are highly energetic, playful, and sensitive dogs, to the point where their energy levels may be too high for very small children. As friendly as they may be, their high energy has Dalmatians needing plenty of exercise and activities, otherwise, they are prone to weight gain, anxiety, and even behaviour problems including irritability and aggressiveness (especially with other dogs) as they also tend to bark excessively. And unfortunately, the fad had a side effect of irresponsible breeding and inappropriate adoption, as many were unprepared to handle their high energy.

But back to its name and supposed origins. Dalmatians are believed to be named after the coastal area of Croatia. They are a popular symbol in Dalmatia; when visiting the region, one can buy souvenirs such as plush toy Dalmatians at any local gift shop. Aside from the theories of the breed being from Egypt, Greece, or France, it could also have come from Roman Illyrian Dalmatia (the northwestern part along the Adriatic Sea) from white hounds with black or brown markings.

In fact, the first written document about the Dalmatian dog comes from the archives of the Diocese of Đakovo in eastern Croatia, where the Bishop of Đakovo Petar Horvat described the state of the economy in 1374, in which he covered the different livestock including the dogs bred in the area. Among these, the Dalmatian dog is mentioned as “hunting dogs 4 to 5 palms tall (60 to 75 cm), with short white hairs and black round spots on various parts of the body. These freckles have a diameter of about 1 to 2 fingers. That is why it is called “Dalmatian dog” (Canis Dalmaticus).”

Whatever the true history may be, it’s no secret that the region of Dalmatia prides itself on the breed. Everyone likes dogs, so why not use that as a marketing opportunity? In fact, the city of Zadar (located in the very heart of Dalmatia) planned in 2018 to launch the first pedestrian crossing with dots instead of tracks. Led by entrepreneur and tourist guide Sandra Babac, the “Zebra Dalmatinka” came from the need to place a pedestrian crossing as a shortcut between the famous Zadar Sea Organ and Greeting to the Sun monuments, and as an opportunity to promote the connection between Dalmatia and the Dalmatian dog, which according to Babac is not used enough to market its supposed country of origin in the world. There have since not been any known updates to this story, but we can only imagine how iconic the attraction could be, and what a brilliant tribute it would make to the four-legged enigma.

For more, check out Made in Croatia.

Split County Supporting Several Cultural Heritage Preservation Projects

ZAGREB, 24 Jan 2022 - Culture Minister Nina Obuljen Koržinek on Monday held talks with Split-Dalmatia County Prefect Blaženko Boban on cultural projects that the county has prepared for the next multiannual period including the construction of a museum within the fortress on the island of Vis.

Addressing the press after the meeting, which was held in Split, Minister Obuljen Koržinek underscored the construction of a new museum in the fortress on Vis Island, the Salona archaeological site, the Archaeological Museum in Split with its focus being on Salona - and the further exploration and presentation of that ancient locality.

We also discussed the ancient Stećak tombstones and I would like to mention something we discussed ten days ago in cooperation with the Ministry of Agriculture and a new project to finance agriculture on archaeological and protected historical sites, she said.

Split-Dalmatia County has three sites listed on the UNESCO list, the minister said. She added that it is the only county that have as many as three conservation departments, which bears witness to the intensity and wealth of its cultural heritage.

The ministry is aware that no matter how much is invested in preserving this rich heritage, that will not be sufficient. Hence it is necessary to identify priorities and in that regard to further invest in cultural heritage because of its value, the importance for the community and huge potential to attract tourists, the minister said.

Choosing Between Living in Zagreb or Dalmatia, Two Years Later

December 16, 2021 - After getting to know the capital of Croatia better this year, I was already imagining my life in Zagreb. However, one has to think twice before leaving Dalmatia behind so easily.

Seven months in Rijeka, and eight in Podstrana, which is located about 20 minutes south of Split. That is the time that, until March of this year, I had spent in Croatia since I arrived for the first time in October 2019. At that time I felt an urge to get to know the country beyond the coast, and Osijek was my main choice. Unfortunately, things did not work out for me to move to Slavonia, and my next destination would be Zagreb.

The impact of Zagreb on me was immediate. Parks everywhere, such a walkable city, a great public transport system, things to do everywhere and at all times, movement, life, great food... Zagreb has it all. One of the reasons why I went to Zagreb was to find a job, and this was the case in my second week there. I interpreted it as a sign to realize that my place was there, in the capital of Croatia.

A short video that I recorded and edited on the way from Split to Zagreb, with an emphasis on the landscapes between the two cities.

I would have liked to continue this article by saying that, after a few months, I managed to settle in Zagreb. But one thing led to another, and I ended up in Split after four months. Some will believe that because it was summer the decision was a bit obvious, but at some point, I really saw it possible to spend those hot months away from the coast. In July I returned to help my parents with our accommodation business during the season, and I was not yet financially ready to pay rent. In Zagreb, I was residing in student accommodation thanks to a scholarship, so that made it easy for me to live there.

The view from Lanterna Beach, between the town and the ferry port of Stari Grad, on the island of Hvar. Heaven on earth. (Photo: Jose Alfonso Cussianovich)

I cannot say that I returned with sadness in my soul - the summer was spectacular, and for me, it is always special to be close to my family. The job I have allowed me to work in any corner of the country, so it wasn’t a big deal to move again. The reception of dozens of tourists who arrived during the season and the several beach days made summer go by very quickly for me. In the blink of an eye, it was already September. The climate in Dalmatia was the same or even more pleasant than in the previous months. I was aware that summer 2021 was slowly disappearing, but beach days, ice-cold beers, and air conditioning were still part of the routine. I still remember with great happiness the visit of my cousins, with whom we visited one of my favorite places - Stari Grad, on the island of Hvar. September was indeed a special month.

Zagreb Cathedral, when I visited the capital of Croatia in early October. (Photo: Jose Alfonso Cussianovich)

October came, and I noticed the changes when I made a short trip to Zagreb. The colors of the forests that accompany the E65 and E71 roads changed from strong green to reddish. The week I was in Zagreb, earlier that month, reminded me how much I missed the things I liked about it. That's when I said that, as a goal, I would come back at least once a month even if it's just to visit.

Shortly after that brief stay, I managed to convince my parents to go back together to spend a few days in the capital. We stayed around the corner from the Cathedral, and we really had a great time in those few days.

My parents, in Ban Josip Jelačić square on our little trip to Zagreb in October. (Photo: Jose Alfonso Cussianovich)

My next visit would be last week when it was time to celebrate TCN's Christmas dinner. It was the first time I went to Zagreb with a pre-winter ambiance. Despite the cold weather, I have never seen a city as lively and vibrant as Zagreb is in Advent. I kept reminding myself of the many benefits that living in Zagreb entails, which even go beyond the lifestyle, such as the efficiency of public institutions or the ease of meeting new and valuable people even in such everyday situations.

Zrinjevac Park in Zagreb, during Advent. (Photo: Jose Alfonso Cussianovich)

By then, I was already thinking about the cost of living there and it even occurred to me to try to convince my parents that living in Zagreb and running our business in Split at the same time was a very feasible alternative.

But it was time to return to Split, and in less than a week, I reconsidered everything I had been thinking throughout this year about living in Zagreb. Five things made me change my mind.

One of the many scenes that one can find when walking along the beaches of Podstrana. In this case, between sv. Martin and the Le Meridien Lav hotel. (Photo: Jose Alfonso Cussianovich)

First of all, I decided to walk along the beaches of Podstrana, from Saint Martin to the Le Meridien Lav hotel, during sunset. It is definitely not the ideal time to take a dip in the sea, but just being close to the Adriatic Sea is more than enough for me and I couldn't afford to be so far from the sea. This almost spiritual walk has been crucial for me to think things over.

The view from the mountain, in Podstrana, next to the church of sv. Juraj. Below right, you can see the city of Split. (Photo: Jose Alfonso Cussianovich)

Secondly, the little hikes I made to the upper part of Podstrana these last two days, both on a small hill behind my house and on the mountain where the small church of St. Juraj is located. In recent weeks, gray skies, cold weather, and storms prevailed. But when I returned from Zagreb, I found sunny days, warmer weather, and stunning sunsets. The images I captured of these last two days, both in photo and video, speak for themselves. Never in my life have I witnessed such spectacular views, and that’s not an overstatement.

A short video that I recorded and edited in Podstrana, where I live, between December 14th and 15th. The sunsets were spectacular.

Third, the Split Winter Tourism roundtable. I had the great opportunity to be present at the previous meetings and at the great event held at Chops Grill on Monday. Although my role was quite minimal, the important thing for me was being able to listen to many of the people who in recent years have moved mountains to make Split a twelve-month destination and those who could finally make it happen. Self-criticism, ideas, potential collaborations, their will... all this helped me to think that the future in Split can only be better, especially if intentions and actions go hand in hand this time. It excites me to think that, with the skills and ideas that I have, I can be part of that change, in some way.

The Split Winter Tourism Roundtable, which was held at Chops Grill on Monday. (Photo: Jose Alfonso Cussianovich)

Fourth, and you probably think that I let it slip when I remembered October: the olive trees. "Who in his right mind chooses one place for another, just for the olive trees?", you might ask yourselves. It is not so much for the trees themselves, but for the experience. I was aware that the olive harvest season began in mid-October, and after missing the opportunity to see it up close at the Olive Picking Competition on the island of Brač, I decided to be more attentive to the slightest chance to live that experience.

One of the photos I took while accompanying some neighbors from my neighborhood while picking olives from their trees. (Photo: Jose Alfonso Cussianovich)

Fortunately, behind the building I live in, there are many olive trees. For several days I looked to see if someone was coming to collect the olives, and indeed one day it happened. Without thinking twice, I walked there with my camera and asked a family of three if I could take some photos of them and record some videos while they picked the olives. What at first seemed like a journalistic task, turned into a very friendly afternoon in which we shared stories, and especially the father, who told me for hours everything I should know about a tradition as ancient as collecting olives. You know that as you go up the highway towards the mainland, the olive trees begin to disappear. You probably think it's a bit of a silly reason, but I just don't see myself living far from these kinds of experiences. Truth be told, one of my dreams is to have my own olive tree and make my own olive oil. So there you have it.

Last, and maybe most importantly, my Croatian ancestor, Pero Kusijanović, was born in the small district of Mokošica, in Dubrovnik and was, by all means, a true Dalmatian. Pero migrated to Peru approximately 150 years ago, and I don't think he would have ever imagined that his descendants would choose to return and settle in Zagreb, far from the Adriatic. I will honor him, in some way, trying to move my future forward here in Dalmatia.

My father (right) visited the house in Mokošica, where our ancestor, Pero Kusijanović, was born and raised. (Photo: Patricia Medina)

I will never regret the experiences and moments lived anywhere other than here. If something makes a country like Croatia special, it is that each of its square kilometers has something prepared for you, and capable of marking you for life. But I do have to admit that there have been times when I underestimated the beauty of living in Dalmatia, and for that, I apologize. Sometimes you don't have to make pros and cons lists to compare one place to another. Sometimes the region has a vibe that is difficult for others to feel or understand, as the great Daniela Rogulj would say.

Many believe that Dalmatia is only the islands and the coast (which alone are good reasons to settle here), but many are unaware of the history and beauty of places Knin or Sinj, the latter I was able to visit at the end of October with my family and really blew me away.

Split, Zadar, Dubrovnik, Šibenik, Ston, Trogir, Korčula, Hvar, Knin, Sinj, Primošten, Omiš, Makarska... how can you forget about these places and many others with such ease? Sometimes it is about what a place already is, and sometimes what a place can become. For the moment, I choose the latter. There’s so much for me to discover here before jumping to conclusions, or Zagreb.

For more, check out our dedicated travel section.

October Blues: Imagine the Global Economy Had a Dalmatian Work Ethic

November 27, 2021 - Some in Dalmatia want winter tourism, others are exhausted after the season. How would things look if the global economy adopted the Dalmatian work ethic?

I love Dalmatia.

I love Dalmatians. Hell, I married one, and she is as lovely as ever, as well as one of the most dedicated and hard-working people I know.

My wife got that work ethic from her father, who is from the village of Brusje on the island of Hvar. One of ten kids, there was never money for anything, and the 12-kilimetre round-trip walk to school in Hvar Town each day certainly kept him fit. Without ever taking a kuna of credit in his life, he managed to buy land in the most prime part of Jelsa, build a 4-storey house and put all four kids through university, while at the same time spending hours in the family field each day, supplying the family with much of its food.

Total respect, and I am only sorry that he did not get a proper son-in-law who loved to spend time in the field and not on a laptop, or at least one who adored blitva...

When people say that Dalmatians are lazy, I always smile and think of my father-in-law, who is always on the road about 5 am each day to tend to the field before his daily chores. I think of the many Dalmatians who left the country in the 19th century, who emigrated out of economic necessity with little more than the shirts on their backs and went on to build incredible businesses and new lives in countries where initially they did not even speak the language. Seriously impressive stuff, and I read somewhere that if the Croatian diaspora was its own country, it would be one of the richest in the world in terms of GDP.

And yet...

I know I am going to get slaughtered on social media for this article (particularly by those who don't read beyond the title), and I am ok with that. When you have a double lawsuit ongoing from the Kingdom of Accidental Tourism, a little additional social media abuse it like water off a duck's back.

I am also aware that nothing will change with anything that I write, for a learned a long time ago that there is a reason that Dalmatia seems to be a little slower in time, without all the latest brand stores and latest technology - the locals like it that way. Like many foreigners coming to Dlamatia over the years, I used to get frustrated at the lack of local interest in embracing change and things that I called 'progress'. The reason these things did not exist were because locals did not want them. It took me 15 years but I managed to condense my advice to incoming foreigners into one sentence. If they could accept and live by this sentence from day one, they would truly have found paradise. But if - like me - you spend years fighting against that sentence before finally accepting its truth, a long period of frustration ensued. The sentence is this:

Do not try and change Dalmatia, but expect Dalmatia to change you.

Dalmatia definitely changed me - for the better - and I long ago gave up trying to change Damlatia. But there is one small area where I think I can contribute to a small change that I think would be beneficial to all, and it is one which divides locals.

Winter tourism.

Not many people know that organised tourism in Europe began in Dalmatia.

With a focus on the winter.

The founding of the Hvar Health Society in 1868 attracted convalescing aristocrats in the Austro-Hungarian Empire to rest in the temperate climes of the island known as the Austrian Madeira. Even as late as 1990, winter tourism was rocking, with Americans coming for up to 6 weeks for the art, nature, food and wine - read this fascinating interview with a UK tour rep based here from 1986-91. Croatian Winter Tourism in 1990: Full of Life! Tour Rep Interview.

The issue of winter tourism comes up each year, and I always smile at the responses. We are tired, we have worked so hard in the season. We made enough in the season, we don't want it. I have to attend to my olives and fields etc. It is October after all, and the season has now been a full six months.

While I used to smile at this more when I actually lived in Dalmatia, it is somehow a little less amusing living in continental Croatia, where people work equally as hard, usually without the benefit of lucrative tourism that happens accidentally, and they have to slog it out 12 months to survive.

But that I guess is one of the joys of being born a Damatian in Dalmatia - it really is God's own paradise.

The thing is, though, that this seasonality is - at least in the humble opinion of this foreigner, if he is allowed one - is that it is really affecting the quality of life in Dalmatia, and I think this seasonality is becoming a real issue. Living on Hvar was an incredible experience, and running TCN kept me shielded from the extremes due to the interesting assignments that constantly popped up. But the reality is that during the season, most people are working 5 jobs to make the most they can in the season, and in the winter, there is nothing open to enjoy.

I was in both Osijek and Split this month, and there is no question which is the better city to live in during the winter. And it is not the Dalmatian capital. Split SHOULD be one of the top cities in Europe for lifestyle. It has so much to offer, and it has the potential to be one of the most attractive remote work destinations in Europe. And yet sadly, it is showing signs of esging towards overtourism in summer and a strangulation of life in winter. It really doesn't need to be that way.

One of the most interesting points in TCN's recent winter tourism initiative (which has led to the Split winter tourism round table with Mayor Puljak and others on December 13), was in this great interivew with the team from The Daltonist, who lament the lack of local life in town. This is detrminental both to tourism, as people want to exeprience the local vibe (did I mention Osijek?), but also it is not that much fun for locals either.

Not all people want to work all year in Dalmatia. And that is fine - that is one part of the essence of the Dalmatian lifestyle. But others do. Why not look at rather than working 12 hours a day 7 days a week for a seasonal worker, who is then unemployed during the winter, perhaps closing for a day or even two each week to give the staff a chance to breathe and enjoy life a little. At the same time, work with others to develop content and local life, so that things are open longer. By moving away from seasonality, workers can be given permanent contracts, find stability and become invested in the company's success.

And there would be life in winter. And that would be a win for both tourists and locals.

And creating content and fun out of season need not be that complicated or successful. Build it and they will come. Check out Nomad Table by Saltwater Nomads at Zinfandel each Friday through the winter in Split. A sell-out each week.

But imagine that Damatian work ethic of only working for half the year was applied to the global economy. Those Wall Street brokers and the like who work 50 weeks a year so that they afford the fortnight in Croatia on the Dalmatian coast - now working for just 26 weeks and staying home, with the appropriate mild negative effect on Dalmatian tourism. In fact, if all of Dalmatia's visitors only worked half a year, how many would be able to afford to come to Dalmatia at all?

The difference is, of course, that they are not Dalmatian, living in God's Own Paradise.

Do not try and change Dalmatia, but expect Dalmatia to change you. But build in a little winter tourism for those who want it - it will improve the quality of life all round.

Read more about the Split Winter Tourism initiative, which will take place on December 13.

Did You Know These Lesser Known Facts About Dalmatian-Venetian Relations?

November the 8th, 2021 - Dalmatia and Venice have had quite the tumultuous relationship over the last few, well, thousand years or so, but did you know these lesser known facts about Dalmatian-Venetian relations? Put yourself to the test!

As Morski/Gordana Igrec writes, Dalmatian-Venetian relations used to be extremely complicated in the past, with trade issues and jealousy when it came to the former Dubrovnik Republic, which was once its own state, dominating. Their structure and relationship changed over time. Here are some lesser known facts.

Back in 1553, the Venetian representative Giovanni Battista Gistuiniani, when travelling through Dalmatia, wrote the following for Sibenik: ''the costumes of the inhabitants, their speech and their customs... everything is Croatian. All of the women dress in a Croatian style and almost none of them can speak Italian!''

For Trogir, he wrote: ''the population of this city lives according to Croatian customs. It's true that some of them dress in the Italian way, but these examples are rare. Everyone can speak Italian, but they still speak Croatian in their homes, and that's because of the women, because few of them understand Italian, and if they do understand it, they won't speak any language other than their mother tongue. The nuns in Sibenik, as well as others across Dalmatia, speak only in Croatian.''

When Venice took over Dalmatian cities, it didn't allow the clergy access to the great noble council, nor to the popular assemblies. (According to today's interpretation of that decision, the clergy had no influence on public and political life at the time.)

Back in the 15th century, there were bloody conflicts between nobles and commoners in Split, Trogir, Hvar and Sibenik.

There were no serfs in Dalmatia for the Venetian authorities! People were divided into nobles and commoners. Back in the 16th century, the bourgeoisie began to form in some Dalmatian cities.

Venice dealt Dalmatia the hardest blow when on January the 15th, 1452, its Government ordered that all merchandise in Dalmatia must be exported only to Venice and to no other place.

Even before the arrival and subsequent takeover of the Venetian Government, Dalmatian cities almost all had public schools.

In 1848, Emperor Ferdinand issued a patent granting freedom of the press, determined the National Guard and the convocation of deputies of the provincial estates so that all of them together could draft the Constitution which he had determined. Dalmatian intellectuals then enthusiastically accepted the idea of the Habsburg emperor.

While the continental Croatian city of Varazdin, far from Dalmatia, was under the Habsburg monarchy, the capital of Croatia sought the accession of Dalmatia to Croatia, because it once belonged to it. A similar law was passed by the City of Zagreb on the same day, emphasising that: "Dalmatia belongs to Croatia by law, history and people."

For more on Croatian history, check out our dedicated lifestyle section.