What’s keeps Croatia going? A new report yet again suggest it's tourism. And then you have tourism. Sometimes there’s an uptick in tourism. The highest-growth sector is tourism. Investors see a lot of potential in tourism. Tourism is another sector trending upward. Don't forget tourism!

Have we also mentioned tourism?

Tourism.

You’ll probably feel like you’ve read this story before. And maybe you have.

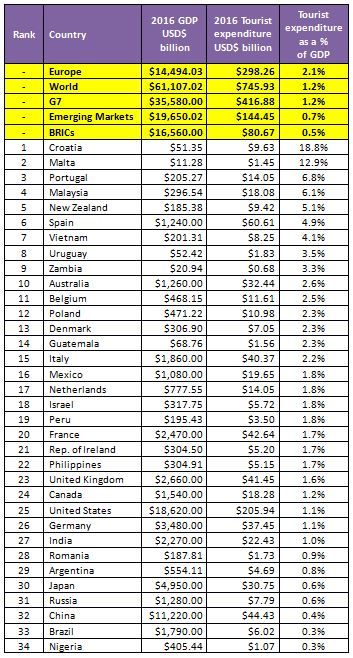

A report by London-based consultancy network UHY claims tourism spending accounts for about $9,6 billion, or about 18,8, percent of Croatia’s gross domestic product (GDP). The figure puts Croatia, the EU’s newest member, well above the 2,1 percent average across the continent and by far the most tourist-dependent of the countries studied.

Croatia ranked eighth in growth from tourism revenue, with a 9,1 percent increase, putting it behind nations such as Canada, Vietnam and overall growth-leader Nigeria, with an astronomical 159 percent increase in revenues from tourism.

UHY’s report focuses on 34 countries, comparing tourism spending growth over the two years leading up to 2016 between European economies and emerging markets around the world; figures show the latter growing two times as fast as mature markets on the European continent (2,2 compared to 1,1 percent).

“Tourism can be a major supporter of job creation, entrepreneurship and business growth in their economies, but it needs constant investment,” said UHY Chairman Bernard Fay.

Croatia itself has benefited overall from its tourism apparatus, according to UHY’s Helen Budiša, who suggested government strategies such as a reduced value added tax and tax breaks on service industry-related expenditures have driven growth.

Digesting the Data

A closer look at the data shows Croatia’s an outlier, and not in a positive sense. Malta is the only other nation with tourism representing a double-digit chunk of its GDP, at 12,9 percent. Afterward, the rates plummet to half as much, all the way to a fraction of a percent.

Economic powerhouses such as the UK, US and Germany rank near the bottom of the list, with tourism representing less than 2 percent of their overall economies. It barely registers in China. Granted, megalith economies with mammoth industries may not be a fair point of comparison.

It’s not only about size though. Comparably-sized economies which have GDPs similar to Croatia’s $51,3 billion are well below its 18,8 percent dependency. In Uruguay and Guatemala, with GDPs of $52 billion and $68 billion respectively, tourism spending accounts for less than four percent of GDP.

Data from the European Commission economic directorate shows demand for tourism is more sensitive to economic variations than any other Northern Mediterranean country (translation: an increase in the EU’s GDP leads to a bigger uptick in Croatian tourist arrivals than, for example, Italy).

Croatia’s homogenous economy is already showing signs of strain, after a record 2017 which saw 18,5 million arrivals, according to the Ministry of Tourism.

Not All Is Well

The season faces a natural barrier, stymied by Croatia’s temperamentally-short tourism season, bookended by Bura winds and soggy springs and autumns. This prevents tourism's positives from carrying over into other sectors of the economy.

Whereas Greece’s tourism season lasts from April until the end of October, 75 percent of Croatia’s tourism revenue come in just July, August and September. The tourists don’t travel far to get here either.

Whereas Greece’s tourism season lasts from April until the end of October, 75 percent of Croatia’s tourism revenue come in just July, August and September. The tourists don’t travel far to get here either.

An overwheliming majority of Croatia’s tourists come from neighboring or nearby countries — Italy, Slovenia, Austria and Hungary are among the nearby nations which supply nearly two-thirds of the Croatia’s tourists.

Turning Down Jobs You Don't Want

The dependency on tourism has begun showing strains upon the social fabric as well. This summer, many seasonal jobs along the coast remain unfilled. The government recently increased the quota of foreign workers allowed into the country. And for good reason.

While on assignment in Hvar last summer for some other publication, I interviewed Ljubo Jurcic, President of the Croatian Association of Economists. The message was dire.

“[Tourism] shouldn’t be more than 10 percent of GDP; it’s simply a sign of lackluster manufacturing,” he said.

He pointed to a massive chasm between the workforce Croatia’s economy needs and the actual workers it produces.

A nation with a 19 percent dependency on tourism shouldn’t have empty service industry and culinary schools, he said. Croatia needs cooks, waiters and hotel managers. It’s producing engineers and economists instead.

Students know if they do not find work in their field of study within three to five years after graduating, their diplomas become worthless pieces of paper, he added.

This, more than anything, is fueling the mass exodus now seen in Slavonia and Dalmatia’s hinterlands, Jurcic contended. That exodus is now felt in Dalmatia’s cafes and restaurants as well.

“We’re going to lose more than one generation of potential workers,” he said. “Even our cooks go to Germany to work.”

All this, Jurcic surmized, for a low-stability industry which he called “spontaneous by nature.” Pointing to Croatia’s current moment in the spotlight, Jurcic said, “It’s a cycle. Something becomes a hit. Then it’s all spent and it’s gone.”

A Fickle Industry

“Tourism in Croatia just sort of happens,” Jurcic said. “This is turning into the Dutch disease,” referring to the economic phenomenon of a sudden influx of foreign currency into a country, to the detriment of the overall economy.

Mato Bartoluci, a tourism professor at the University of Zagreb’s School of Economics, also warned about the lopsided figure, especially when paired with low manufacturing.

“Too often, we import goods,” he said. “If we build our own products, the overall value of tourism would increase.”

UHY’s report says Europe’s tourism hotspots have hit a ceiling despite having more attractions, as limited opportunities to expand infrastructure put the brakes on growth.

London’s Heathrow Airport, for example, is humming along at 98 percent capacity. Germany’s new Berlin Brandenburg Airport is already years behind its scheduled 2011 opening, and has fast become a nationwide boondoggle.

Croatia’s clogged border crossing and kilometer’s long bottlenecks showcase a similar strain. Upgraded airports in Zagreb, Dubrovnik and Split may help, but only so much.

Bartoluci sounded a caustic warning: “Tourism alone cannot maintain the economy.”