Croatian Woman Declared Missing in Ireland, Gardaí Appeal to the Public for Help

February 9th, 2022 - Iris Hrvoj, a 33 year-old Croatian woman currently residing in Ireland, has gone missing from her home in Drogheda, Co. Louth

She has been missing since the early hours of Tuesday, February 8th, 2022. The Irish Gardaí published a statement appealing to the public for help in tracing the woman’s whereabouts.

Iris is described as being 5’ 5” (167cm) in height, of slim build, with short blond hair and blue eyes. It is unknown what Iris was wearing when she went missing from home.

It is thought that she may be in the Harolds Cross area of Dublin.

Anyone with information is asked to contact Drogheda Garda Station on 041 987 4200, the Garda Confidential Line on 1800 666 111, or any Garda Station.

Hrvoj is a trained dancer and a licensed fitness, yoga and pilates instructor. A native of Zagreb, she moved to Osijek for university where she went on to open a dance studio in 2017, as reported by 24sata at the time. It is yet unknown when she relocated to Ireland.

5 Things I Miss About Living in Ireland

Less sentimental, more practical: a fitting description for things you'll miss about living in a foreign country, compared to those you like best about your homeland. A look at a few things that Ireland does just right

In recent weeks I’ve been writing a lot about my impressions of Ireland as a Croatian emigrant. Looking back to some of the previous pieces, I feel I’ve been a bit too critical for the most part: who can afford those rent prices? The weather is awful! Eesh. One would think I was dragged there against my will.

On the contrary - I find the country and its people wonderful and I really enjoyed the experience overall. Since I’ve already come up with a list of things I missed about Croatia, it’s only fair that I present a few counterarguments because there are quite a few things that Ireland does just right. Such as…

1. Pubs & pints

Surprise, anyone? I didn’t think so. Irish pubs serving Irish beer exist all over the world, including Croatia, but they just pale in comparison to the real thing. There’s something about the essence of a real Irish pub that can’t be put into words: it’s an institution, a place of gathering, a source of joy, a home away from home. And the pints? Good Lord. The Croatian craft scene has really taken off in recent years, but it’ll take quite some time before we see a dozen outstanding local beers on tap in an average neighbourhood bar.

Gonzalo Remy / Unsplash

And look, I get that people are homesick and want to hold on to something familiar. But seeing an occasional Croat ask where they can get Ozujsko or Karlovacko in Ireland just makes me sad. Get yourself to the nearest pub, you ingrate, and get a proper pint.

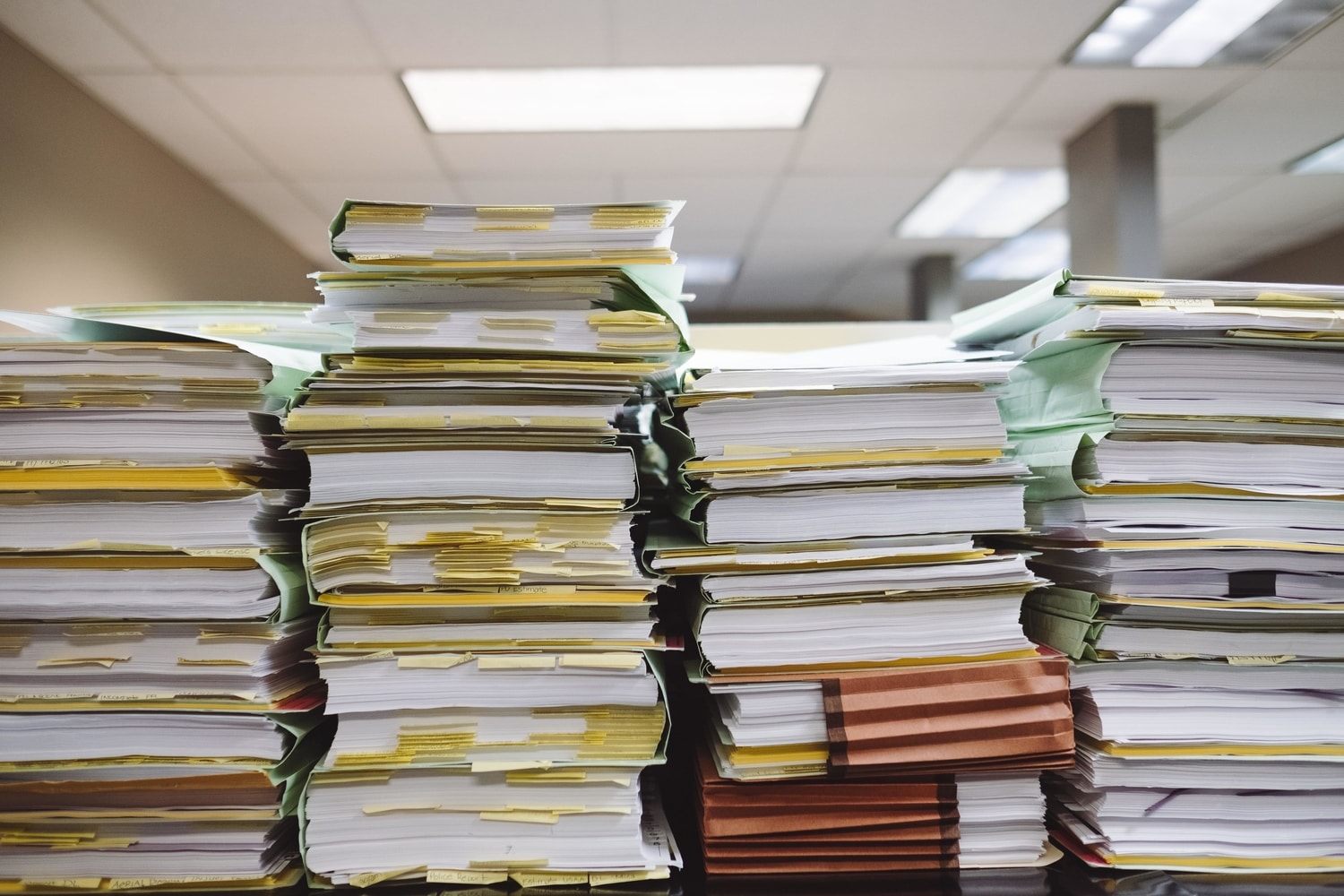

2. Never missing 'one more paper'

One of the things I liked most about living in Ireland was the absence of the Kafkaesque bureaucratic machinery that Croatia is notorious for. I brought along a folder chock-full of personal documents: birth certificate copies, translated degrees, tax reports. Domovnica? Sure, you never know, whispered the tiny voice in my head, battered and bruised by countless government office mazes, fees, duties and stamps.

The folder went unopened for the next three years. Most things are done online these days - I booked an appointment to obtain a PPSN (Personal Public Service Number, the Irish equivalent of OIB) before I even arrived in Ireland. Revenue, the much more positive-sounding counterpart of Porezna uprava, has a fantastic comprehensive website and an equally great online service where filing your annual tax return only takes a few clicks.

Wesley Tingey / Unsplash

Sure enough, Croatia’s making progress in this regard as well; e-porezna and e-citizen services come to mind. The main difference, however? The few times I was required to show up in person someplace, the clerks and officials in Ireland were friendly and helpful, and I never, ever heard the dreaded ‘you’re missing one more paper’.

3. Friendliness

Continuing from the previous point, the Irish are exceptionally friendly, welcoming people. Walk into a shop, a pub or an office and chances are, you’ll be met with a smile and a warm greeting that always feels genuine. The habit is delightfully contagious. I’m not particularly skilled in small talk and usually keep to myself, but found myself engaging in many a chat about the weather or current events with pleasure.

This kind of positivity is rare in Croatia; cashiers, bus drivers, waiters and clerks seem to be cranky most of the time. Instead of a friendly hello, you’re more likely to get a ‘what the hell do you want’ look. Okay, we all have bad days, but I wish we weren’t quite so bitter sometimes. I felt welcome wherever I went in Ireland, and I now find myself missing the chit-chat.

4. International cuisine

The other day, I saw an ad for a Thai restaurant opening in Rijeka and I positively squealed. International cuisine doesn’t really have a presence in my town and currently totals one Chinese restaurant, one Spanish restaurant, and two sushi places. Zagreb has it much better in this regard, but beyond the capital or perhaps the leading tourist destinations on the coast, you won’t have much chance of exploring other cultures’ gourmet specialties.

Cork was a different story. Owing to immigration from all parts of the world, Ireland is growing more diverse with time and so is its food scene. I had a great Syrian bistro across the street from my place, dozens of Chinese and Indian restaurants to try out, and my favourite find was a Nepalese restaurant which served phenomenal dumplings and curries so intense and flavourful, they made my head spin.

International grocery stores are scattered all over town. You won’t have any trouble sourcing various imported foods if you’re looking to switch up your weeknight cooking and practise making something new and delicious. Once you get accustomed to this, combing the aisles of Croatian supermarkets in search of a good oyster sauce can get pretty frustrating. Some ingredients are either extremely hard to find or ridiculously expensive in comparison to their prices in Ireland.

To be fair, this is not an exclusively Irish thing, but it just goes to show how much we love convenience - it's easy to get used to most things being easily accessible.

5. The scenery

Sean Kuriyan / Unsplash

The Irish landscape is so spectacularly beautiful, it helps tolerate the unforgiving weather. It’s not like Croatia lacks in natural wonders, it’s just that Ireland looks different. The steep dark cliffs rising from the ocean, vast stretches of sandy beaches, lush green pastures dotted with cows… Absolutely stunning. Bad weather doesn’t diminish the beauty of this land; overcast skies or a bit of rain and fog only add a mystical, atmospheric quality to the environment.

While I did long for the unparalleled Adriatic views while I was away, I must say I grew quite fond of the Atlantic. I’ll miss the cliffside hikes and the unreal colours found on the Irish coast.

For more news and features from the Croatian diaspora, follow the dedicated TCN section.

The Realities of Croatian Emigration to Ireland, Part II: Work

Continuing our series on Croatian emigration to Ireland, a look at the topic that drives most people to emigrate in the first place: jobs, paychecks and everything in between

To paraphrase a pop art icon, just what is it that makes Ireland so different, so appealing? To any Croatian person frustrated with their miserable economic prospects, it’s always been all those jobs that are readily available. It’s so easy to find work!, people will tell you. And it pays well!

After three years in Ireland, I have a bit of perspective in this regard, so... Let’s unpack that.

1. The land of opportunities

Ireland was widely known for having the fastest-growing economy in the EU year after year since 2014… until a pandemic threw a wrench in it. Much like in the rest of the world, Covid-induced lockdowns caused unemployment to soar - from 5.9% in July 2019 to 19.1% in July 2020. The trend kept up this year as well, and things only started to look up after the reopening of outdoor hospitality in summer.

The labour market in Ireland is not expected to recover to pre-pandemic levels of employment until 2024. Not the best time to set sail for Ireland in search of a better life, perhaps. It’s quite a depressing picture, and the prospects for those living in Ireland don’t seem promising at the first glance. And yet… Despite all troubles in the last 18 months, there was a 56% increase in job vacancies on the Irish employment market in Q3 2020 after the initial crash. A year later, and a quick look at the leading job sites shows there’s no shortage of work available.

Markus Spiske / Unsplash

Let’s start with the group that seemingly made the best choices in life. Anyone working in IT would likely score a job in the time required to read this article - tech tops the list of leading industries in Ireland, and not without reason. Low corporate tax and the constant influx of skilled international workers have foreign investors flocking to the only remaining English-speaking EU country. Google, Twitter, Facebook, Microsoft, PayPal and other tech giants set up their European headquarters in Dublin; Apple has a base in Cork. Engineers, developers, data scientists, analysts and the like will always have their pick on the market as IT experts remain highly sought after.

For the rest of us mortals, there’s the wide umbrella of the tertiary sector. Most immigrants to Ireland, including Croatians, are likely to seek employment in hospitality, hotels, customer service, healthcare and assisted living, beauty and wellness, grocery retail, repair and maintenance, etc.

Etienne Girardet / Unsplash

Etienne Girardet / Unsplash

There’s a massive labor shortage across other industries as well: transport, construction, manufacturing. In recent years, Irish employers have expanded their search to the continent, hosting open days in several Croatian cities at a time in hope of attracting a skilled workforce. Nurses and caregivers, professional drivers and warehouse operatives, all are in constant demand.

2. Dynamic, fast-paced environments

There are three main ways to find a job in Ireland. Recruitment agencies make the process more streamlined and less stressful for jobseekers who have only just arrived and have yet to get acquainted with the intricacies of the job market. Depending on the industry and the employer they represent, some agencies will also assist new hires with relocation and paperwork.

There’s also the tried and tested ‘door to door’ method - you’ll often see a ‘staff needed’ sign on display when entering a shop or a deli. It’s not unheard of to print out a few copies of your CV, walk around town for a while and land a job in a day or two.

Looks about right. / Markus WInkler, Unsplash

And finally, there are job sites such as Indeed, Monster and Jobs.ie. They’re probably the most popular method of seeking employment and also a nice way to suss out what the job market’s like at any given time of year. Take the holiday season, for example. With Christmas fast approaching and shoppers about to go berserk, there’s a noticeable uptick in demand in customer-oriented occupations.

Anyone who’s ever worked in the lower tiers of hospitality, retail or any kind of customer service would tell you that for the most part, it’s miserable, soul-sucking labour. Well, HR departments bend over backwards to make it seem otherwise, coming up with dramatic ads that often obfuscate what the actual position entails.

It’s a wild wasteland of ‘vibrant’, ‘high-energy’, ‘fun’ work environments.

A prospective cashier will thus have an ‘exciting opportunity’ to ‘become an ambassador’ for the brand’s business. Hotels offer ‘fantastic new vacancies’ for ‘accommodation assistants’ and list ‘ambition to develop’ among the main prerequisites to join the cleaning staff. Gone are the days of straightforward job descriptions. Job titles are replaced with ludicrous synonyms that are meant to sound more exciting or more important, but end up being neither: call-centre agents have evolved into support professionals, advisors, specialists, executives and gurus.

Speaking of gurus, it’s getting hard to discern whether you’re about to join a workplace or a cult. ‘What does living fully mean to you?’, asks an ad for a reservations agent. It’s a lot to consider. As you become part of a ‘close-knit family’ that’s ‘customer-obsessed’, you’ll be ‘resilient and disciplined’ and - my favourite - ‘take instructions with enthusiasm’.*

Ian Schneider / Unsplash

It’s a heavy burden to carry, suddenly becoming an executive or a spiritual leader where you thought you’d only have to answer the phone. Expectations are piling up, with Irish employers demanding years of experience, strong initiative, attention to detail, resilience, discipline, emotional intelligence, warm personality and full flexibility to work shifts within a 16-hour window with schedules changing at a moment’s notice. All things considered, if you see ‘excels in a dynamic, fast-paced environment’ on a CV, it’s code for ‘capable of doing seven things at once under pressure and accustomed to dealing with verbal abuse’.

This is not exactly a groundbreaking revelation, I know - and none of it is exclusive to Ireland. Our tourism-oriented country is heavily dependent on the service industry, and nonsensical corporate language slowly seeps into the Croatian job market as well.

The thing is, that ‘fantastic new vacancy’ in Dublin pays three times as much as you would get for the same shitty job in Croatia. In fact, you get paid two to three times more for low-skilled work in Ireland than you would be in a job requiring a university degree back home.

Emigration 101.

3. The cost of living

The national minimum wage in Ireland is €10.20 per hour (before tax), which is set to increase to €10.50 from January 1st, 2022. To put this in Croatian terms, an average single person working full-time on a minimum wage will soon be earning around €1600 per month net.

At present, the monthly minimum wage in Croatia is roughly €450 net (3400 HRK), set to increase to €500 (3750 HRK) next year.

No wonder the grass seems greener on the other side. Average and median pay in Ireland is even higher, but the majority of foreigners moving to Ireland for work won’t start with an average salary. I’m purposely using the minimum wage as an example, as I feel it’s a more realistic comparison between the two countries that also helps us consider what the bare minimum can get you here and there.

There are many factors at play, of course, and we can’t just straight up compare apples and oranges. What about expenses? It’s not just wages that are higher. I dedicated a whole article to the housing crisis in Ireland, and it’s true that rent alone will eat up a substantial portion of your paycheck. Childcare and car insurance are no joke either. Bars and restaurants are more expensive. So is tobacco. Entertainment costs more in general: nightclubs, music, theatre, cinema. Don’t get me started on hairstylists. It adds up, and if you covet the finer things in life or have any vices to sustain, you’ll need to start climbing the career ladder asap.

Markus Winkler / Unsplash

Here’s the catch, though: in proportion to wages, basic needs cost less in Ireland than in Croatia. To put it another way, less time is spent working in order to afford certain essential goods or services. Rent aside, okay.

Food is the worst offender. Even though we’re all aware that food prices are inflated in Croatia, the extent of it doesn’t really hit you until you’ve returned from Ireland where you earned three times as much, yet groceries somehow cost the same or less than back home. These days, you’ll find us haunting supermarket aisles and woefully voicing our thoughts to no one in particular. ‘Ha ha, look, coffee costs the same as in Tesco. Wait, 25 kuna for oat milk? That’s almost doub- 30 kuna for budget brand rice? 30?? FOR RICE??’

Then there are utilities. Our monthly bills (internet, gas and electric) were only marginally higher than in Croatia. Also, water supply is free. No water bills. Wild.

We try not to be those people who return to Croatia only to start every sentence with ‘well in Ireland, it was like-’, but some days are harder than others.

Once you’ve covered all your basic living expenses, outrageous rent included, you can do a whole lot more with your discretionary income than you could in Croatia. I moved to Ireland in late 2018; in the following year, I paid off a small debt, took a total of 8 international trips ranging from a weekend to 2 weeks in length, and was able to afford all the things I wanted without having to cut corners, only earning a bit more than the minimum wage for the bigger part of the year.

The same job in Croatia would pay enough for me to live month to month and take trips to the local bar once a week. Which brings me to my next point...

4. Dignity and (self)respect in the workplace

You go through a certain transitional period when you move from Croatia to Ireland and start making a steady income. It’s called ‘boy do I have a shitton of money all of a sudden’, lasts anywhere from six months to a year, and involves a lot of frivolous spending. No more depriving yourself of nice things in the name of electric bills! You can now have both - and more! Once the adjustment process is over, you sober up, start budgeting and set up a pension fund.

Jokes aside, viewing your job, your salary and your worth objectively is a skill that takes a while to master. Salaries are discussed in annual amounts before tax, unlike the Croatian monthly net ways we’re used to. Coupled with the higher living standard in general, this makes every figure sound desirable at first. You don’t know the nuances and implications of 19k, 25k, 35k - it all seems like a lot.

What about the kind of work you’ll take on? Suppose you’re not highly skilled in one specific field. If you’re emigrating for economic reasons, you won’t be terribly selective when you first arrive and if needed, you’ll aim lower than usual until you get settled.

How low would you go, and how long would you stay there? The former is a no-brainer; an entry level position will suffice to get you going even if it involves low starting pay. You want to sort out all the paperwork as soon as possible, rent needs to be paid, and honest work is honest work. The latter, however, is where things get complicated. What do you want to make of yourself? How do you measure success?

Alex Kotliarskyi / Unsplash

Take my example. I wanted to get the ball rolling as quickly as possible, so I took a job in customer service I was overqualified for. It soon became apparent that starting over from the bottom creates a certain dichotomy in your self-awareness. The person you are in your home country and the person you are in emigration only partially overlap, both sides engaging in constant dialogue: I have a master’s degree, but take calls for a living. I earn a Croatian MP’s salary taking calls for a living. This is not what I want out of life. This allows me to live quite a comfortable life. I used to declare I would never leave home. I made a conscious decision to be here. And so on, and so on. This unavoidably messes with your head for a while. It’s an uncomfortable process.

Granted, I moved up with time and changed roles within the same company. My salary increased as well, I picked up a few new skills, and the camaraderie we had going on the floor made the daily grind more palatable. The work itself, however, remained unfulfilling, and in normal circumstances, I wouldn’t think twice before looking elsewhere for something better suited to my skills and interests.

But since I wasn’t planning on staying long-term, I let inertia take over. This is okay!, I thought, this is okay for the time being!, all the while not exactly knowing how long that time being would last. It ended up lasting longer than I expected. I built a good reputation for myself, had amazing colleagues and a great rapport with my superiors, paychecks were rolling in, and I got comfortable.

My salary was modest for Irish standards, but served me well enough and I wanted for nothing. I felt valued. This seems to be the case with plenty of other people I’ve met: well-educated, competent individuals, some with a lot of experience under their belt, accepting positions well below their skill level and staying, as those positions awarded them a better quality of life than a managerial rank in Croatia ever did.

This is not to say that employers in Ireland shouldn’t pay their workers more, or that we should settle for peanuts and never aim higher as long as we can get by - on the contrary. But it answers the question of why so many people adjust their criteria significantly when they move to a foreign land to seek work. I’ve seen quite a few vicious articles and comments disparaging people who left Croatia for Ireland ‘only to scrub toilets in exile’. How dare they sell this as a success story? They weren’t willing to do any scrubbing until now, Croatian toilets not good enough for them?

Not when they don’t earn you a living, they’re not. Irish toilets are much better in that regard, along with their offices, call centres, hotels, warehouses and supermarkets. Regardless of profession, workers are respected in Ireland, overtime is paid without fail, and paychecks show up on bank accounts like clockwork. It’s not all milk and honey, but for the most part, the business culture is much healthier than in Croatia. It was nice to experience living in a country where entrepreneurship is encouraged, and breaking into the public sector isn’t the ultimate career goal.

This is a highly subjective topic, and there’s no universal experience which all Croatian emigrants share when it comes to labour. I don’t want to make it seem like all of us work menial jobs and never move up in the world. Some chase promotions, some start businesses, some make the big bucks, some return home disillusioned after a few weeks. Most just want to live a dignified life and then take it from there - and Ireland, on her part, sure provides plenty of opportunities for growth.

*Everything in quotation marks is a direct quote from various advertisements on Jobs.ie accessed on 1/11/2021.

Read the first part of the series on Croatian emigration to Ireland - accommodation.

For more news and features from the Croatian diaspora, follow the dedicated TCN section.

Realities of Croatian Emigration to Ireland, Part 1: Accommodation

October 16, 2021 - We are delighted to welcome back Nikolina Demark, the TCN Writer of the Year in 2017, who is now back in Rijeka after her 3-year assignment to report on Croatian emigration to Ireland. Part 1 - the accommodation reality.

In October 2018, I moved to Ireland. I had one box of clothes shipped to my partner in Cork and boarded a plane with a carry-on and a backpack. My one-way ticket cost me €32.

A few years and one pandemic later, we’re back in Rijeka, Croatia. It was our plan from the start and we’re happy to be home again.

This isn’t a novelty: we followed in the footsteps of more than 20,000 Croatians who had moved to Ireland in the last decade or so. Some have returned, some have not. Countless reports and impressions have been sent our way from the Emerald Isle, and it often seems like there’s nothing more to be said.

Well, I’ll say a few things anyway. I’d like to offer an overview of my experience, but instead of pointing out the obvious in a few bullet points - The weather is bad! But there are many jobs to be had! - let’s take an in-depth look into the realities of moving to Ireland.

Starting with the most sobering reality of them all….

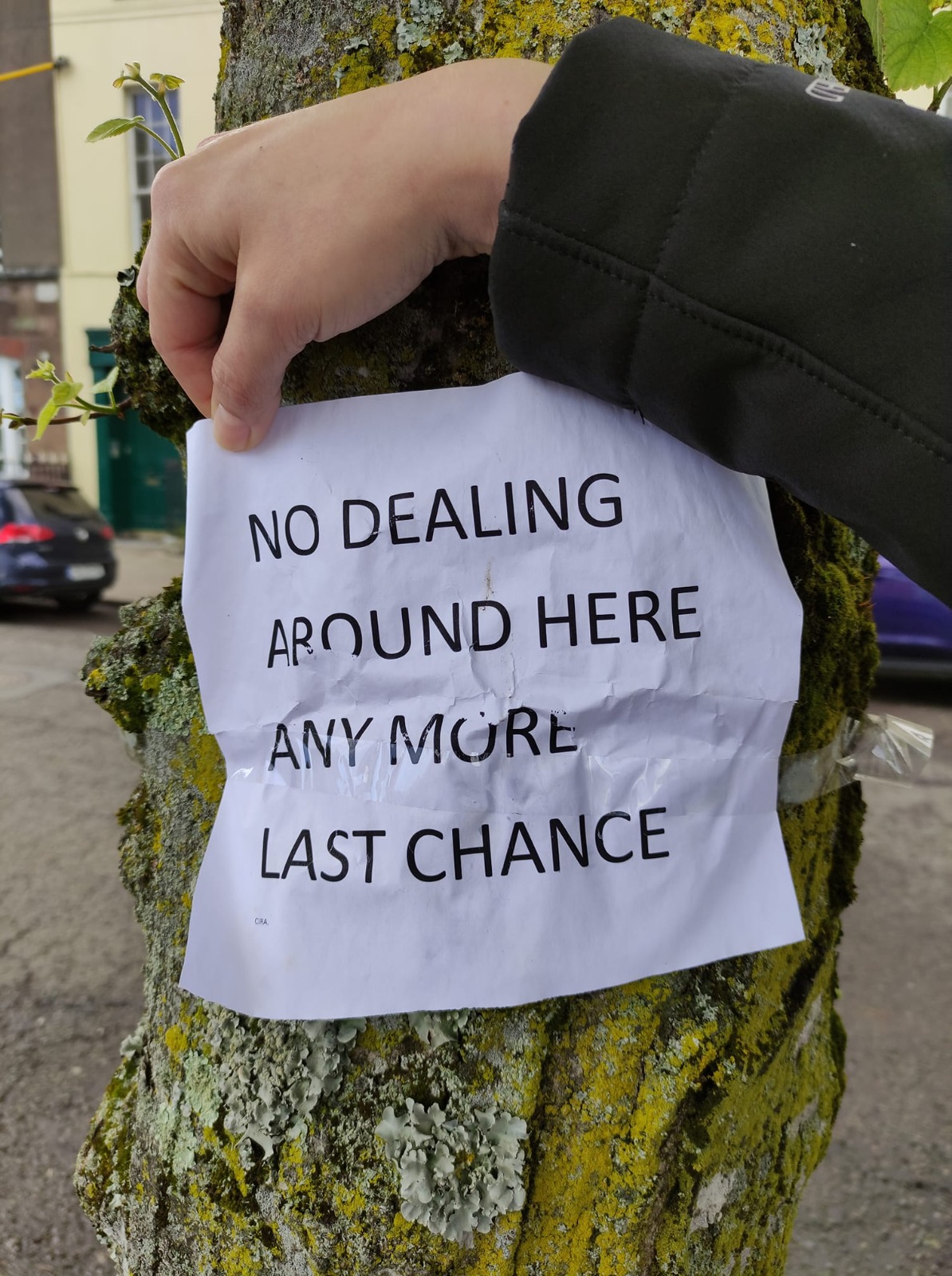

The rampant housing crisis.

It’s become a well known fact that it’s much easier to find a job in Ireland than a place to live. The situation has been dire for years now but keeps getting worse - whether you’d like to rent or buy, the housing crisis has everyone jumping through hoops to find accommodation. The hoops are on fire. Everything’s on fire.

There’s a critical shortage of homes to rent: in August 2021, there were only around 2400 properties available for rent nationwide. Outside of Dublin, that total drops to 800. In the entire country. Houses, apartments, rooms and sheds get scooped up as soon as the listings go live.

As I’m writing this, Daft.ie, Ireland’s leading property website, shows a total of 54 apartments available for rent in Cork city, which has a population of roughly 190k. All were listed in the last week or so, each having amassed a couple of thousand views already. I’d bet you a few have been taken off the market in the time it took me to finish this paragraph.*

The demand far outweighs the supply, allowing the landlords to dictate pricing as they see fit. Rent prices are skyrocketing and showing no sign of deflating anytime soon: the average monthly rent has doubled over the last decade, from €742 in 2011 to €1477 in 2021.** Dublin city tops the list with an average rent of €2035, followed by Cork city where the average currently stands at €1524.

Compared to that, our one bedroom apartment in Cork city center which we got for €1150 a month in late 2018 now almost seems like a fabulous deal. Cork city is a Rent Pressure Zone, meaning that the annual rent increase for any given property is legally capped at a fixed rate of 4%. This helps to a certain extent, but most property owners have been making the most of those 4% in recent years, squeezing every last available cent out of their tenants.***

Can you even afford that?

Technically, yes. But it’s not going to be much of a budget.

When I first moved to Ireland, almost 50% of my monthly paycheck went towards my share of rent and utilities - and my starting salary was more than the minimum wage. A raise or two later, the same cost of living was equal to a third of my monthly pay. It’s manageable, and I was getting by pretty well on the rest of my disposable income... but if I had pets, kids, a car, debt, or any other source of expenses, it would have been a different story. More on that in a future blog.

There are ways of cutting costs, of course. Shared accommodation is the most logical option, and the rental offer slightly expands when you’re looking to rent a single or double room instead of the whole property. This will cost you €500-600 a month on average, getting lower the further you move from bigger urban areas. However, the properties often have 4 or 5 bedrooms, and you can end up sharing a house with a few more flatmates than a typical Croatian is used to. It can be rewarding, but it’s also a gamble. I might have seen this as a fun living arrangement 10 years ago, but these days, I’m willing to pay a bit extra for some privacy. Anyone moving to Ireland with a partner and children probably won’t like this solution either.

Housing is cheaper in rural areas, but less populated places go hand in hand with less chance of finding work unless you’re fully remote. Commuting is an option, but can turn into a real headache - infrastructure in Ireland leaves a lot to be desired. Public transport is unreliable or even nonexistent in some places, and you’ll likely need a car to get to the office and back.

Even if you get lucky and score a place at a good location, consider that you’ll have to add a hefty security deposit on top of the first month’s rent in order to move in. This usually matches the monthly rent amount, but can be higher - e.g. we were required to pay a deposit of €1400 for the €1150 apartment mentioned above.

This means you’ll need to have close to €3000 saved up to rent a whole apartment in most urban areas in 2021 - a bit less in the suburbs or smaller towns, and quite a bit more if you’re starting a new life in Dublin. If you’re only renting a room, you’ll need around €1000.

And it’s not just a question of handing over the cash: you will typically need to provide a recommendation from your previous landlord, as well as proof of employment. Some landlords will require potential tenants to present a few months’ worth of payslips as proof of financial stability.

Someone who just landed in Ireland will certainly find all of the above quite challenging. People often start apartment hunting in advance, scouring Facebook groups and property sites. Subletting, staying with friends/family where possible or booking a few weeks in a hostel are the most common ways of finding one’s ground while looking for work and permanent accommodation.

It’s an uphill battle, and it’s not particularly rewarding. When you get to the top of that hill, you’ll find an absence of insulation, poor water pressure and black mold.

Here’s some advice: get everything in writing. If you get invited to a viewing, don’t show up without the deposit and first month’s rent. Request and keep receipts for every transaction or agreement you’ve made. Take photos of every single nook and cranny in your house the moment you move in. If you’re a light sleeper, get blackout curtains, as blinds aren’t really a thing in Ireland and the sun rises before 5AM in summer. Don’t wait too long to buy a dehumidifier, and invest in a decent one. Anything under €100 isn’t a decent one.

How about buying?

A year goes by. You do a bit of Croatian emigrant math one day and it turns out your one bedroom apartment has already cost you 100.000 kuna. Two more years pass and the grand total can now buy you a nice little studio apartment in Croatia.

When you move to a country with a higher living standard, you quickly learn it’s not wise to do any conversion of this kind. It’s self-torture, it doesn’t serve any purpose, but it’s so deliciously tempting and you keep doing it anyway.

However, it gets you thinking about all that money going down the drain with nothing to show for it. Croatians and the Irish share a certain obsession with private property - a primordial urge to own the land we live on seems to be ingrained in our respective genetic codes, and long-term renting is still often viewed as failing in life. That, or we just want to stick it to the landlords. So we pay the banks instead.

Shockingly enough, a mortgage is much more affordable than renting in Ireland these days. (The system is broken!, echoes a cry from the crowd.) Specific amounts will vary depending on a few factors, but it’s not surprising to see a monthly mortgage payment amount to half of an average monthly rent. Since it’s likely that the rent surge will keep on surgin’, why not buy now instead of renting indefinitely?

A few reasons. One, property prices in Ireland are out of control. According to the latest quarterly report by Daft.ie, the average price of a property in Cork city currently stands at €307.464. In Dublin, it’s €399.323. The national average? €287,704. I could go on, but you get the gist. The market has seen an 11% growth in pricing this year alone.

Say you really have your heart set on buying a house. First-time buyers are required to pay a 10% deposit and can apply for a mortgage to cover the remaining bulk of the price. Admittedly there are areas of the country where real estate is more affordable, but even in the lower price range, when you tack on a few thousand euro for various fees, you will likely need to save up over €20.000 to be considered a prospective buyer. It’s definitely doable, but takes time and discipline - and the prices will keep inflating while you’re saving for a down payment.

Once you’re ready to buy, finding a property for sale that suits your needs and which you can afford will prove to be a challenge. Supply is scarce, and it’s estimated that only around 20,000 new homes will be built this year, whereas 35,000 more are needed on the market.

What little is built isn’t necessarily available for purchase. It’s typically big international investors that are either financing new developments, or acquiring the bulk of them only to lease them out (again pushing up the rent prices as a result). An average individual looking to buy ends up empty-handed. I have friends and acquaintances who are planning to soon tackle the property market in Ireland, and I can imagine the world of frustration that lies ahead.

We did not have to deal with this particular nightmare, as we had no intention of staying in Ireland long-term. I did think about this a lot, though. From an emigrant’s perspective, it’s one of the turning points on the road to settling down in a foreign country. Years can go by and you can feel assimilated in every other regard, but if you don’t buy a home, are you really committed? Are you really sure you want to build a future there, or are you still just visiting?

Back in Croatia...

We returned to Rijeka in late June and went on to stay with family for the next few months. Knowing we would be going back and forth a lot between a few different locations, it made no sense to rent an apartment right away.

Being able to make a deliberate decision to temporarily live out of our suitcases was a luxury, in stark contrast to Ireland where it often isn’t a question of choice these days. Rent prices are hiking up in Croatia as well, and more expensive rarely equals higher quality of accommodation, but at least there’s accommodation to be found at all.

As weeks went by, I started looking forward to having a home base again. We lucked out and signed a lease for a lovely apartment at a reasonable price in less than a week.

That being said, while I was scrolling through the listings, I was surprised to see that quite a lot of landlords are now accepting applications from college students only. They lease out the apartments over the school year, then have the tenants move out at the start of the summer season so they could rent to tourists from June to October. It’s not a new phenomenon, and it’s been preventing locals from finding long-term accommodation in tourist hotspots such as Split for years now. I just haven’t noticed this in my hometown before, and while I’m glad that Rijeka is becoming more tourism-oriented, I hope this won’t get out of control anytime soon. Or we just might be forced to buy, and with the current prices per square meter….

I guess the grass isn’t very green on either side.

------

*I checked again a few hours later. There are now 39.

**The minimum hourly wage has not kept up with the dramatic inflation in rent prices. It grew from €8.65 to €10.20 - before tax - in the last 10 years. In 2021, a minimum wage earner makes €1584 a month after deductions. If they were to rent at the average price of €1477, they’d have enough left over for a few pints to drown their sorrows in. Of course, this is not a realistic turn of events. I just want to stress how much I don’t like the ratio.

**The 4% rate has been replaced with the rate of general inflation in July 2021.

For more news and features from the Croatian diaspora, follow the dedicated TCN section.

Plenković, Varadkar Talk Brexit, Croatia's Role as EU Chair

ZAGREB, November 22, 2019 - Prime Minister Andrej Plenković and his Irish counterpart Leo Varadkar met in Zagreb on Thursday and talked about Brexit, which could happen during Croatia's EU presidency in the first half of 2020, and preparations for negotiations on future UK-EU relations.

We are confident that Croatia will do an excellent job as EU chair, Varadkar said.

Croatia is taking over the presidency at the beginning of 2020, in the year when Brexit could really happen, he added. Britons are going to the polls on December 12 and if incumbent Prime Minister Boris Johnson wins, Varadkar expects the deal to be ratified soon.

Whoever becomes prime minister and forms the government, we will gladly sit down, listen and work with them, he said, adding that regardless of the election result, he could tell the Irish that there would be no hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland.

Brexit doesn't end with the United Kingdom's exit from the EU but enters the next stage, negotiations on trade, security and political partnership with the UK, Varadkar said.

We expect the withdrawal agreement to be ratified soon and to launch negotiations on future relations, said Plenković. He recalled that if Brexit happened, the EU's Brexit negotiator Michael Barnier would become negotiator for future EU-UK relations.

The UK has been given another Brexit delay until January 31.

Plenković said that reaching an agreement on future relations by the end of 2020 was very ambitious but not impossible because "where there is a will, there is a way."

The two prime ministers also talked about the EU's 2021-27 budget, enlargement and EU membership prospects for Southeast European countries, which will also be the focus of Croatia's presidency.

The European budget should be appropriate and support long term successful policies, such as the cohesion policy as well as the common agricultural policy, which is very important for our rural communities, said Varadkar.

More news about relations between Croatia and Ireland can be found in the Politics section.

Zoran Milanović Heading to Ireland to Talk to Croats Living There

As Novi list/Drazen Ciglenecki writes on the 25th of October, 2019, SDP's presidential candidate Zoran Milanović wants to talk to Croats who have emigrated to Ireland's second largest city in recent years, claiming that he is ''not going there to get votes''.

The Croatian presidential election campaign has, rather unsurprisingly, sunk into near-total monotony. There is nothing going on with it, there are no confrontations between candidates, which is of major interest to citizens and the media everywhere, so it is not surprising that the public has lost interest in this election race almost entirely. The current campaign is still monitored mainly at the level of the results of surveys that are published periodically. It is up to nobody else but the presidential candidates themselves to arouse more public interest in the upcoming elections.

President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović has not changed any part of her approach to the elections after announcing her official candidacy three weeks ago. She is still distanced from the campaign.

Miroslav Škoro is trying to add a certain international dimension to his candidacy, but for many people it's become more amusing to watch than anything else.

This week the singer stayed at the European Parliament in Strasbourg, where he spoke to members of the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) faction about his own vision for Croatia within the European Union. The visit was organised by MEP Ruža Tomašić, who supports Škoro, and belongs to this parliamentary group to the right of the European Peoples Party (EPP).

Zoran Milanović has been paying visits to different areas in Croatia and making comments on daily political developments, and we've learned that he will soon travel to Cork, Ireland. He isn't planning on giving up on it all and moving there, but plans to talk with Croats who have moved there over the last few years.

In his election headquarters, they emphasised the fact that Milanović isn't ''going there to get votes'', since it is highly unlikely that anyone living in Cork will travel 250 kilometres to Dublin just to vote at the Croatian Embassy there. In addition, very few Croats in Ireland participate in the elections at all.

HDZ strongly attacked the former government headed by Zoran Milanović for the level of emigration from Croatia after the country officially joined the EU back in July 2013, but this worrying trend has not stopped with the change of government. The President of the Republic of Croatia was particularly engaged in this matter, warning the Government of Andrej Plenković that he must adopt demographic measures that would at least mitigate the scale of emigration.

''We stopped the military aggression, Croatia won. However, today, especially Slavonia, Croatia is at risk again. It is threatened with emigration and extinction,'' Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović once said firmly.

In her meetings with Croats living abroad, she constantly urges them to return, and she told them a month ago in Pittsburgh, "Croatia is calling you." Zoran Milanović has repeatedly spoken about this issue during the campaign, denying that people are being evicted because of a specific government. However, he also managed to find a culprit in HDZ.

''Croatia is a country where there is no equality, no equal chance of success. We see it every day and that's why people leave. They leave because they see that, even when they put in a lot of effort into something and when they play by the rules, there's no success. Unfortunately, this is a consequence of a Croatia which has been suffering under HDZ for thirty years. HDZ is a cartel, if you're with them, you'll succeed if you are not, you have no chance,'' the SDP presidential candidate said this summer.

Emigration of young people has been emerging as one of the most difficult problems in Croatia, so Milanović claims that he wants to hear directly from the people who left their homeland about what prompted them to do so, and what their chances of coming back look like.

It is estimated that about 20,000 Croats live in Ireland today, of which about 125,000 are located in Cork. Half a year ago, they wrote to the Embassy in Dublin and the Ministry of Science and Education in Croatia requesting the opening of a Croatian school in Cork, given that their children were forgetting how to speak Croatian.

Make sure to follow our dedicated politics page for much more.

Croatian Couple Return from Ireland, Pay Off Debts and Buy Car

Going to work abroad seemed to be the only option, and one Croatian couple spent a year in Ireland but returned to their homeland, just like other people do, as they say.

As Poslovni Dnevnik writes on the 24th of October, 2019, after 20 years in journalism, frustrated by a stressful job, low pay and an exhausting work pace, he decided to start a "new life" along with his wife.

But after just one year, they returned to Croatia. They only went to Ireland to make money to pay off their debts, Deutsche Welle writes.

"It was a very, very good experience. With the fact that I earned something, I gained something that is much more valuable - I lost the fear of existential problems. Because now I know I can go anywhere and live and work there. Nobody here can ever say to me, 'If you don't do it, there's someone who will work for the minimum wage'' again, I've learned to appreciate my time and my work.

I no longer care what I'll do if I lose my job, fail at a company or quit. It's an enormous burden taken from my shoulders. It is a release from the existential fear that most Croatian citizens live in. so I'd recommend everyone to go and try out their skills. If we all had that experience, then it would be a lot different here too,'' Soudil says as he begins the story.

"What was very important in making that decision was the fact that my then girlfriend and now wife was still out of work, so one day we sat down and talked. Many of our friends were already in Ireland. We got in touch with them and got information that we could make three to four times more over there than here. It was a big step, a big decision. You leave your parents, friends, your lifestyle and you're aware that you're going into the unknown and that your life will change completely. Honestly, that decision was not at all easy'' says Soudil.

"We were fortunate not to go to Dublin, we went to Letterkenny which is all the way north and is a small town. The size of the Đakovo, but much more urban and I won't say nicer, because there is nothing nicer to me than this here. I progressed in my work in just a few days. I worked for an agency that rents apartments and homes out and I can only say that I was valid and respected there, and paid properly for the work I did,'' Soudil says.

Immediately upon his arrival, he was offered to work four hours a day, but he refused because work and a better salary were the reasons why he left Croatia. As he says, his job was not demanding, and no one complained about his work ethic or the quality of his work.

"For the last four or five months, I've been doing another job because I realised that I could still make around 40 euros a day, and the money is welcome. It's easy when there are jobs and they treat you properly."

According to Soudil, having Croatian passport is a kind of job ''recommendation'' because the Croats are well known for being hardworking and responsible employees.

He says they repaid all of the debts they had Croatia off in just three months and even managed to buy a car on top of that.

"When we left, we didn't say: We're never returning to Croatia again. We went to see what it was like to make some money too, to cover the foreclosures and debts we had here. We had unpaid bills, foreclosures for parking, electricity... We paid back all the debts that we'd inevitably accumulated in Croatia in three months and we even bought a car,'' says Soudil.

He describes life in Ireland as extremely enjoyable and nice. He says it never happened that he was "missing one more paper" during administrative tasks, an all too common situation when dealing with Croatian state bodies. A person who has lived in Croatia and dealt with any sort of Croatian administration feels a sort of cultural shock when they're greeted kindly at the bank as if by their best friend, even though you're complete stranger, just getting off the plane, Soudil notes.

"At the age of nineteen, I started working in journalism, I was aware that I couldn't do that business there [in Ireland], but I lived in the belief that I didn't really know how to do anything else. My hobby when I was a journalist was a kind of woodworking, processing metal, electrical work... I learned this from the urgent need not to have to pay professionals to do those things and that it was enough for me to just be able to manage. I'm far from being a professional, but I realised that I could do a lot of other things,'' he explains.

He also says that nobody in Ireland ever asked him what school he graduated from and what kind of "papers" he has. Another shock for anyone who has done anything the dreaded Croatian way.

"It's important here if you have a certificate, there, what's important is whether or not you want to work. The employer is ready to invest in you to educate you at their own expense and give you the opportunity according to your abilities. In one whole year, nobody asked me for a diploma, a birth certificate or a certificate of impunity,'' Soudil tells Deutsche Welle.

Upon his return to Croatia he did well. He is now in a better-paying job that he is comfortable with, and as he says, if he ever begins to get sick of it again, he has a job waiting for him in Ireland.

"Ireland is great, but it has one drawback - it's far away. Anyone who works in Munich can spend almost every weekend in Osijek, which is a big deal when nostalgia grabs you,'' he says.

His wife Lea has a slightly different life story - she was born in Germany, lived in London and working in a foreign country is nothing strange to her.

"I found a job right away. I first worked as a maid, and as they saw I knew several foreign languages, they transferred me to the front desk," Lea says.

Despite the nostalgia, she does not regret engaging in the Irish experience. Because, she says, she tried a hundred things she had never had the opportunity to try, see, eat, do...

"With just three weeks of wages we bought a Mini Cooper, second-hand, but you couldn't even do that in your wildest dreams in Croatia. There are big differences in life here and there, but when everything is put on paper, it's still the best at home," concludes Lea.

Make sure to follow our dedicated lifestyle page for more.

Deputy Parliament Speaker Visits Ireland to Discuss Emigration

ZAGREB, January 22, 2019 - Croatian Deputy Parliament Speaker Željko Reiner, who is on a two-day official visit to Ireland, met with Irish political and Church leaders for talks on Croatian emigrants, the economy and the situation in Croatia's neighbourhood, read a press release issued by the Croatian Parliament's public relations office on Tuesday.

Reiner held talks with Prime Minister Leo Varadkar, the First Vice President of the European Parliament, Mairead McGuinnes, and the Archbishop of Dublin, Diarmuid Martin, according to the press release.

The talks focused on excellent relations and good bilateral cooperation and cooperation within EU institutions.

Reiner thanked Archbishop Martin on his assistance in setting up the Croatian Catholic Mission in Dublin, underlining the importance of spiritual leadership for numerous Croats who have found a new home in Ireland.

The archbishop said Ireland had also had the experience of its citizens leaving abroad, adding however that a large number of them had returned with new experiences and knowledge. Reiner said he too hoped that Croatian emigrants would return to their homeland.

The talks also focused on Brexit, trade and the political situation in Croatia's neighbourhood, the press release said.

They cited tourism as the sector with the largest cooperation potential.

More news on the Croatian-Irish relations can be found in the Politics section.

Facebook Looking to Hire Croats Living in Ireland

The main condition is that candidates know the Croatian market, society, culture and language.