International Poetry Day Croatia: Non-Croatian Poets about Croatia

March 21, 2021 - In honour of International Poetry Day Croatia, TCN's Ivor Kruljac met with non-Croatia poets to share their views on Croatia through their art.

Since 1999 and the 30th General conference of UNESCO, March 21 is recognized as International Poetry Day. As said by the United Nations official website, the date was dedicated to poetry to celebrate „one of humanity’s most treasured forms of cultural and linguistic expression and identity“, which history remembers practiced in every culture on every continent.

„Poetry reaffirms our common humanity by revealing to us that individuals, everywhere in the world, share the same questions and feelings“, states the UN.

Supporting linguistic diversity and an opportunity of endangered languages to be heard within their communities along with encouragement to bring back the oral tradition of recitals, the promotion of poetry teachings and poetry in the media, as well as connecting this ancient art form with other art forms such as music, painting, and theatre, are all goals of the International Poetry Day. And here at TCN, we want to do our part and connect poetry with what we always struggle to report on: Showing all aspects of Croatia.

To the fans of contemporary poetry, it's no secret that poets today are very much alive, productive, and regularly present their work. If not in books then at poetry events, open-mics, and on social networks – either from their private accounts, blogs, or in groups dedicated to this wordy-art.

We asked non-Croatian poets through social networks and private group chats dedicated to poetry who either visited Croatia or know about Croatia to send us poems about Croatia with a promise that the top 5 will be published and authors presented. Now, to be fair, while the author of this article is a poet, that is far from being a legitimate poetry critic and the rest of the TCN's editorial team (at least to public knowledge) aren't even poets. The idea was to pick the poems based on how it resonates with us as individuals who gave the art a chance. The academic acknowledgment is nice, but resonating with the audience, the everyday people, should be the goal of any art publically displayed, right?

To be honest, there wasn't really any competition as, by the end of the deadline, we received only four poems. Nonetheless, the beauty of these poems and great resonation with TCN was there and we are happy to publish these poems and ranked them, from fourth place to the very best. You can decide for yourselves which poem you like best (and the messages you see in their work), but here the four poems that „knocked on the doors of our mailbox“ (metaphorically, quite poetically, speaking).

#4: „Croatia“ by Jesus McFridge

Poets such as Charles Bukowski and Walt Whitman are very well known by their name, but just as in many other arts, poets are no exception in sometimes preferring to use pseudonyms to present their work while keeping their identity unknown and privacy secured. Such is the author that goes by the name of Jesus Mcfridge. Quite active in a Facebook group Poetry Criticism For Cool Cats, he revealed in his application that he is from California and described himself as a „24-year-old American that watches too much television“. He added that his knowledge of Croatia is limited to the country at the 2018 FIFA World Cup, but he has fallen in love with the Croatia national football team's checkered uniforms. Despite never visiting Croatia, after „Croatia's tragic loss in the 2018 World Cup final“, he found himself also crying just as many Croatians did.

„In this poem, I have attempted to capture the feeling of this tragic loss that we have shared together, despite the vast seas that separate us“ concluded Mcfridge in his application.

His bittersweet poem simply titled „Croatia“ indeed brings some painful memories but presented in a short and funny way allows us to look at the past in a brighter way, bring back smiles, and give us the strength to cheer for our Croatia national team as they prepare for the next trophy hunt.

Croatia

They

Almost won

The world cup

But

Mandzukic scored

An own goal.

Jesus Mcfridge © Jesus Mcfridge

#3 „Daniela's song“ by Christian Sinicco (English translation by Daniela Sartogo)

Christian Sinicco was born in Trieste, Italy, and his poetry is published in various anthologies and magazines and an editor of the magazine Argo with which he has dealt with the widest overview of poetry in the Italian dialect from 2000 to the present day. He published three books of poetry: „Passando per New York“ (Lietocolle, 2005), „Ballate di Lagosta“ (CFR, 2014) and „Città esplosa“ (Galerie Bordas, 2017). He won the first Italian Slam Poetry Championship and served as the president of the slam poetry association LIPS - Lega Italiana Poetry Slam (2013-2014) and is the current vice president of Poiéin. He is also active in a global initiative of slam poets organizing the world slam championship which early results can be followed on Twitch.

He participated in numerous book festivals including four festivals in Croatia: Zagreb Contemporary Poetry Festival, Forum Tomizza (in Umag), Pula Book Fair, and Rijeka Book Fair.

His second book of poetry „Ballate di Lagosta“, translates as Lastovo Ballads and it's actually a preview while Sinicco plans to soon publish the full book dedicated to this beautiful Croatian island on the southern coast.

„I was on Lastovo several times. I know a poet from there, Marijana Šutić and I spent a vacation there with other poets such as Ivan Šamija and Silvestar Vrljić“, said Sinicco in his application where he offered a poem from „Lastovo ballads“ which already seen its presentation on a prestigious literary site Versopolis.

„Daniela's Song“ may not bring out the most visual and most explicit Croatian motives, but the discrete and specific localization of Croatia is there all wrapped in a love poem to touch the heart and help us remember the summer sweethearts and romance in Croatia.

Daniela's song

I.

She talks about how beautiful it is without knowing where to go

perhaps into the water of the sun like her cheek

simply necessary as the wet dream

in a wider galaxy if it can be understood,

she seduces you through valleys and dusty vineyards

with eyes towards the bay with the waterfall:

Za Barje the sign said, and so also barked the dog tied

under the cypress – his teethed mouth was the buried reason

the fishermen had left him there – near a house

covered with ivy and blackberries, in which had grown

an apple tree with sour fruits and roses

that only you will taste:

avoiding the asphalt and dirt road holes you followed Daniela

targeting yourself and the asphyxia of your life

that follows the path to erect the intelligence of the species

that on the concept of work has built its republic of theft,

then you saw her dancing on the beach between the warm rocks

and the boat pulled out of the lobster pot, the fishermen are back:

good and evil are triangles of waves that spread

on the sea towards the two islands where we swam

– the fish are not aware of it,

and so the man under the pine and his child

with the mask, another fisherman with the fishing line,

only you maybe on the petals you bite as the words

II.

after quite a while we are outdoors and eat figs

at dusk time on this meadow

sliced on the wooden bowl,

we take the bread and tear it many times

because paradise is close to the fire

and the village to our left rises white in pink

made with scales like the barracuda

Korčula has no intention to leave our sight

I shouted as my usual self

you lit the candle and made me notice

we are not alone, but you can stay calm

slowly also the hut

and its fire have become attractive

calming the natural tension

of a darkening sky, not preventing us

from tasting the happiness

of a grilled fish, of tomato and capers

you are attractive when you smile

with a glass of water on the lips

too quietly they get up,

wanting to be born in the response they seek outside

the people at the tables next to us, and from the cottage

where they grill they come to clear up

a woman and the cook, as in a ceremonial

we ask for the check with the hands

they will be intertwined when we emerge from the field

toward the parking lot where we’ll get in the car

and head out to the highest point

of a series of bends, before descending to the valley

the vault of stars surprises us

we stop everything, propped on pillows of a land

that is still hot, we’re sure

that the star will fall, and it comes true

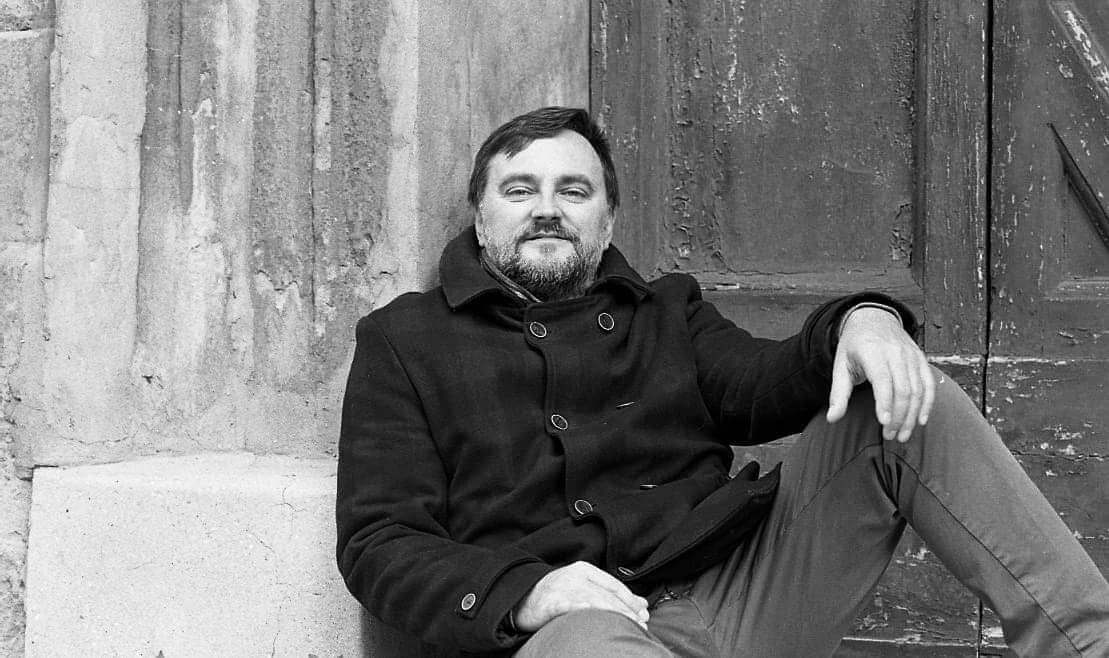

Christian Sinicco © Daniele Ferroni

#2 „The Lakes of Plitvice“ by Vanni Schiavoni (English translation by Graziella Sidoli)

Born in Manduria, Italy, but living in Bologna, Vanni Schiavoni published five poem collections: "Nocte" (1996), "The Suspended Balcony" (1998), "Of Humid and Days" (2004), "Salentitude" (2006), and "Walnut Shell" (2012). He also published two novels "Like Elephants in Indonesia" (2001) and "Mavi" (2019) and edited the poetic anthology "Red - between eroticism and holiness" (2010). Most recently, he also published poetical plaquette „Croatian Notebook“ which features twelve poems dedicated to six Croatian sites: Plitvice Lakes, Kornati, Šibenik, Trogir, Split, and Dubrovnik. Schiavoni wrote the "Croatian Notebook" after a week-long journey in the summer of 2017. His birthplace Manduria is located in the region of Puglia which is 30 miles away from the Pelagosa (Palagruža), the most distant Croatian island, and his surname originates from the name of the Slavonia region in Eastern Croatia.

„For me, it was not just a holiday trip but a journey in and out of everything that I am, a travel diary through which to bring out the game of mirrors between me and that place, between what I am and where I come from and what I have encountered“, said Schiavoni. This journey impacted him with images of the signs of Italy engraved in stone, mournings of the war, communist history („most heretical Communist party in the east in front of the largest Communist Party in the west“, as Schiavoni puts it) and as he added, „the same Adriatic Sea which gives both of us fishes and earthquakes“.

His poem „The Lakes of Plitvice“ is a lovely description of the mixture, the game, and visual eye-candy of the waters in Croatia's oldest National Park, and it linked with a search for bravery and the encouraging point that good and beauty can defeat evil and change it to something better.

THE LAKES OF PLITVICE

The first day they always plunge down into the same spot

the river rapids that come to the encountering

of the white river with the black river

and the more we think ourselves ready with our shrewd eyes

the fewer the adjectives made available to us before that wonder:

the green rush pushes our pupils towards a wild frenzy

it pushes them inside the tearful torrents by our feet

in the shrouded darkness of the sequential caves

and in the vertical caverns sculpted

as if by a hand capable of it all.

Yet Judas must have passed by this place

and though perhaps not the one with burning lips

a simple Judas must have become lost

in this mysterious grid of remorse.

These lakes fall into lakes as lashings on yielding branches

they flow into other waters and so they rain

endlessly

and perfectly untouched.

Vanni Schiavoni © Dino Igmani

#1 „Dubrovnik Rock“ by William Vastarella

After Schiavoni and Sinicco, our first-ranked poet is the conclusive evidence there is something so incredible about Croatia it really inspires poetically-inclined neighbors across the Adriatic. Born in Napoli in 1974, William Vastarella is a teacher of Italian Literature, geography, and History. He's has a Ph.D. in semiotics from the University of Bari and writes for several literary and cultural magazines in Italy. He also edited several poetry anthologies as well as semiotic essays. Vastarella visited Croatia several years ago and had a cultural and relaxing holiday on the seaside. „I found her so full of the Mediterranean spirit that I wrote a poem in Italian. I tried to translate it in other words, trying to leave intact the sounds of that memory“, said Vastarella about his poem on Dubrovnik.

The poem „Dubrovnik Rock“ is fantastic in the way, Vastarella visually invokes the images from the history of Dubrovnik (Ragusa) Republic and the relationship it had with Italians at that age with the waves of the Adriatic Sea as the link between Italy and Dubrovnik but also between past and present.

Dubrovnik Rock

Other singers claim to feel

singular vibes in the waves

Nearby this shore,

and so do I.

Ragusa, Dubrovnik

A name is not enough

To trap a soul.

I ask myself

Who’s the other side

Of the other side

As the seawater shuffles.

I touch with my finger

and now I know it’s real

the steel and the wood of the boat

powerful works of man

that wipe out weapons

and I ask no more.

I realize

we have been both

pirates and emperors

centurions and barbarians

through the centuries

each one to the other

a flurry flow

of slavers and Slavs,

slayers and saviors.

Sometimes when the north wind blows,

melting the white in waves,

painting clouds of amazing blues

mirroring the water in the sky,

space seems to become so narrow,

so easy the neighborhood,

then all

the voices of the ancient age

of an ancient game

of thousands lost

in that spot of time,

that spot of sea,

mutate in a mute roar singing

in which merge the rage of riot

and the call for help of a lot

castled in the rock

waiting for a drop of rain to drink

or friend sails on the horizon.

William Vastarella © Vito Signorile

For more about lifestyle in Croatia, follow TCN's dedicated page.

People Also Ask Google: What Language Do They Speak in Istria?

February 25, 2021 – Continuing the TCN series answering the questions posed by Google's People Also Ask function, one that confuses many: what language do they speak in Istria?

Where is Istria?

Istria is the biggest and northernmost peninsula in Croatia and the Adriatic. It lies in the northern part of the Adriatic, in Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy. Geographically, 90 percent of the Istrian peninsula is part of Croatia, while nine percent includes Slovenia.

Most Croatians live in the Croatian part of Istria (68,33 percent), while minorities make up a quarter of the population, of which Italians are the biggest group – six percent. In the Slovenian part, Slovenes make up the absolute majority population. Only one percent of the Istrian surface is part of Italy. It includes only two small municipalities near Trieste, of which the majority of the inhabitants in one are Slovenes and in the other are Italians.

According to the 2011 census, 25 percent of people in Croatia declared their regional identity as Istrian, of which 12 percent live in Istria County, one of 20 Croatian counties. The name for a regional identity developed by a part of the citizens of Istria, mainly its Croatian part, is Istrianism. Thus, regional identification is more pronounced in Istria than in other parts of Croatia.

How many official languages are there in Istria?

Since there are two official languages in Istria – Croatian and Italian – Istria is a bilingual community. Italian is the second official language in Istria since 1994, and the Constitution guarantees the rights to bilingualism in Croatia. Out of 208,000 inhabitants in Istria County, 180,000 stated that their mother language was Croatian, while 14,000 of them stated Italian as their mother language.

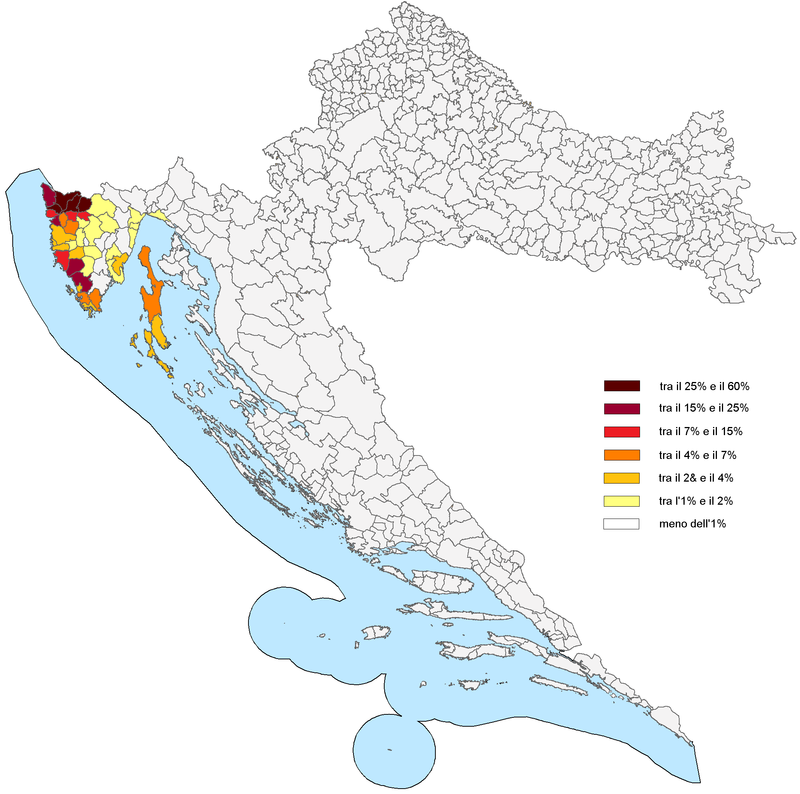

Native speakers of Italian in Croatia according to the 2011 census / Wikipedia

In addition to Croatia's Constitution, local legislation, i.e., the Istrian County Statute equates these two languages in public use and encourages learning Italian as an environmental language. The Istrian bilingual community includes both smaller and larger Istrian settlements.

Due to this bilingualism, Istria is a specific region in Croatia, so there are many Italian public institutions (schools, kindergartens, etc.). Istria has a long tradition of education in another language. Besides, the environment itself is bilingual, which means that Italian is not only spoken by Italians but people of other nationalities too, including Croatians. Also, Istria is historically, culturally, and economically strongly connected with Italy.

Buje, Istria / Copyright Romulić and Stojčić

Reputable cultural, scientific, pedagogical, and artistic minority institutions have been established in Istria: Italian Drama in Rijeka (Dramma Italiano), Center for Historical Research in Rovinj (Centro di Ricerche Storiche), Italian department at the Faculty of Philosophy and departments in Italian for teacher education at the College of Teacher Education in Pula. Also, La Voce Del Popolo, a daily newspaper in Italian owned by the Italian Union (Unione Italiana), is published in Rijeka.

During his visit to Istria last year, Italian Ambassador to Croatia, Pierfrancesco Sacco, said that Italians in Croatia feel at home, like Croats in Italy. This is especially evident in Istria and Pula, where there are a deep friendship and a desire to find new cooperation methods. On that occasion, the Mayor of Pula, Boris Miletić, said that the fundamental values, which have been nurtured in this area for decades, are openness, multiculturalism, and coexistence.

What language do they speak in Istria?

The vast majority of Istrians speak the Croatian language's Chakavian dialect, meaning they use the interrogative pronoun "ča." Only in some parts near the border with Slovenia, some people use the interrogative pronoun "kaj," so they are often mistaken for Kajkavians. Still, the structure and characteristics of these speeches are distinctly Chakavian.

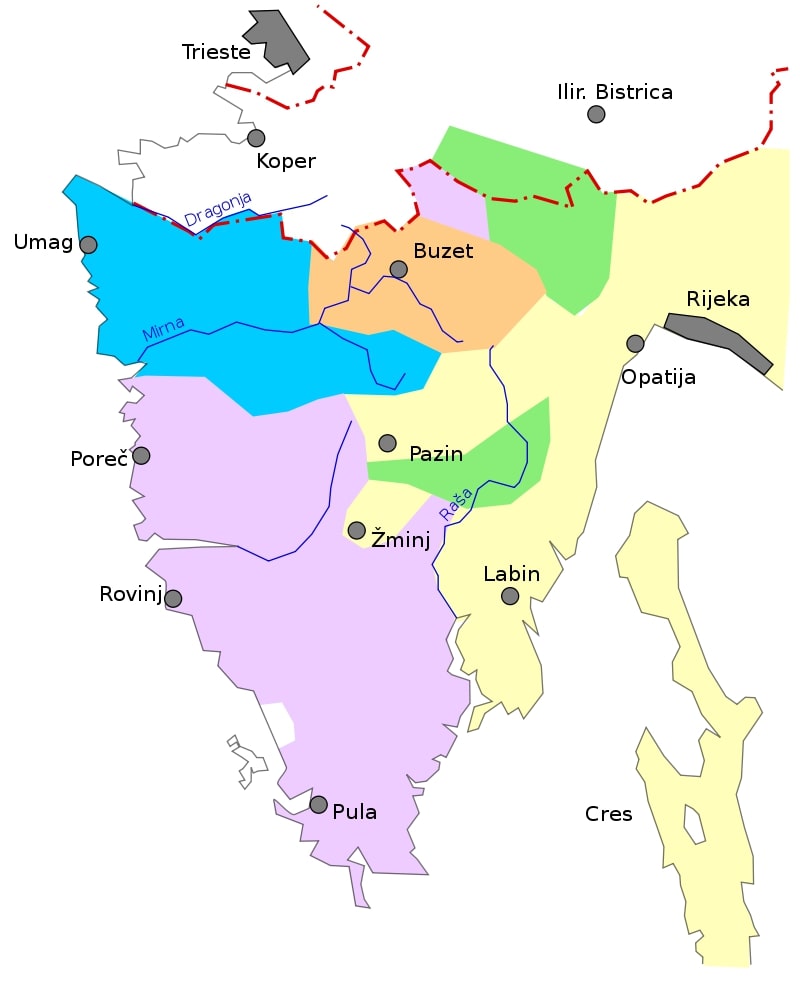

Chakavian dialect is also spoken in Dalmatia. However, the Istrian Chakavian dialect is different from the Dalmatian one due to the numerous Italianisms. It is also difficult to understand it in the rest of Croatia. The most widespread Chakavian dialect in Istria is the Southwestern Istrian dialect. There are also Buzet, Northern, Central, and Southern Chakavian dialects in Istria.

Chakavian dialects in Istria: Southwestern (purple), Buzet (orange), Northern (yellow), Central (green), and Southern Chakavian (blue) / Wikipedia

The aforementioned Italian minority lives in some towns on the Istrian west coast and in some villages near Buje, and they speak Italian. In the Slovenian part of Istria, the Slovenian language is spoken.

In the eastern part of Istria, at the foot of the Ćićarija mountain, in several smaller villages live Istro-Romanians or Ćići, a population of Romanian origin who speak their own Istro-Romanian language, which is a mixture of Romanian and Croatian. Today, many of them have adopted the Croatian language and are now considered Croats.

In addition to the dominant Croatian and Italian languages, other minority languages are spoken in Istria, namely Serbian, Bosnian, Slovenian, Albanian, and Macedonian. One can hear the Shtokavian dialect in Istria as well.

What language do they speak in Istria? Istro-Romanian language

Istria is home to two of the 20 most endangered languages in the world by UNESCO – the Istro-Romanian language and Istriot.

Istro-Romanian language is a Balkan Romance language spoken by only a few hundred people today in the northern Istrian villages of Žejane, Lanišće, and Šušnjevica. It is highly similar to the Romanian language, and for some linguists, the Istro-Romanian language is considered a dialect of Romanian. People in Istria who speak it are called Rumeri, Rumeni, Vlachs, or Istro-Romanians. Croats disparaging started to call them Ćići or Ćiribirci.

In the middle of the 15th century, the Ćiribirci were settled by Ivan VII Frankopan from Velebit on the island of Krk. Since the Ćići plundered Ivan Frankopan in northern Istria in 1463, when their name is first mentioned, it is believed that they immigrated to Istria from Krk. However, Istro-Romanians are not officially recognized as a national minority in Croatia.

The most interesting fact about the Istro-Romanian language is that it was spoken by one of the most famous inventors of all time – Nikola Tesla – even though he wasn't even aware of the ethical existence of the Istro-Romanians. Since elementary school, Tesla was able to speak the Istro-Romanian language, despite the fact that Istro-Romanian was not taught in schools in those years. It was only spoken by a few thousands of people in Istria and Lika, and he could have probably learned it in his family.

Although Telsa always considered himself a Serbo-Croat, one Romanian academic, Professor Moraru, thought Tesla was an Istro-Romanian. When Romanian scholars contacted Tesla in the early 20th century and explained he was of Istro-Romanian roots, he allegedly showed amazement but did not comment on that matter. Therefore, Nikola Tesla has never denied the possibility of his Istro-Romanian origins.

What language do they speak in Istria: Istriot language

Istriot language, often confused with Istro-Romanian language, is a Romance language spoken by about 400 people in the southwestern part of Istria, particularly in Rovinj and Vodnjan. Still, it is also preserved in Bale, Fažana, Galižana, and Šišan. It should not be confused with the Istrian dialect of the Venetian language either.

According to some estimates, the Istriot has only a few dozen active speakers and about 300 people who understand it and can use it in part. It is a Romance language related to the Ladin populations of the Alps, currently only found in Istria. Its classification remained mostly unclear, but in 2017, it was classified with the Dalmatian language in the Dalmatian Romance subgroup.

Historically, its speakers never referred to it as "Istriot language." Instead, it had six names after the six towns where it was spoken: in Vodnjan it was named "Bumbaro," in Bale "Vallese," in Rovinj "Rovignese," in Šišan "Sissanese," in Fažana "Fasanese," and in Galižana "Gallesanese." The term Istriot was coined by the 19th-century Italian linguist Graziadio Isaia Ascoli.

Younger Italians in these places mostly understand Istriot, but they rarely use it, and Croats rule this idiom very badly or not at all. It is most endangered in Fažana, and it seems that it is most strongly maintained in Bale.

What language do they speak in Istria: Istrian dialect in Slovenia

Slovene dialects are separated into a few groups, and the Istrian dialect, spoken in Slovene Istria, falls in the Littoral dialect group. Istrian dialect is spoken in the rural areas of Koper, Izola, and Piran. The Slovenes living in the Italian municipalities of Muggia and San Dorligo della Valle, as well as in the southern suburbs of Trieste (Servola, Cattinara). In Croatia, it is also called the Slovenian-Istrian dialect.

The dialect has been influenced by Croatian as spoken in Buzet and Ćićarija and is further subdivided into the Rižana and Šavrin Hills subdialects.

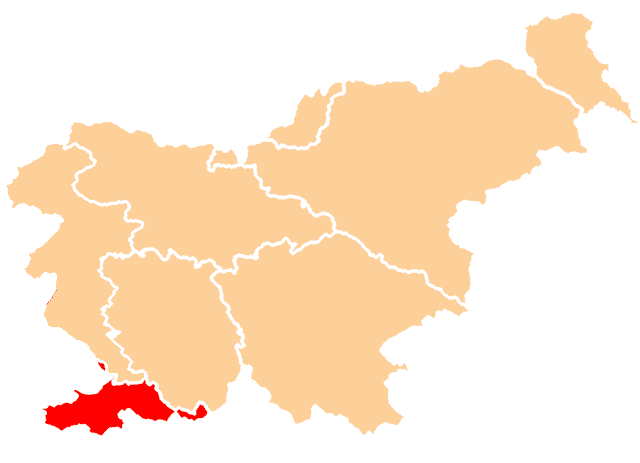

Slovene Istria / Wikipedia

Rižana subdialect (yellow) and Šavrin Hills subdialect (green) / Wikipedia

The Rižana subdialect is spoken in the northern part of Slovenian Istria, in the Rižana Valley east and north of Koper, including the settlements of Bertoki, Dekani, Osp, Črni Kal, Presnica, Podgorje, and Zazid. In Italy, Rižana subdialect is spoken in most of the municipalities of San Dorligo della Valle and Muggia south of Trieste and some southern suburbs of Trieste, especially Servola.

The Šavrin Hills subdialect is spoken in the Šavrin Hills south of a line from Koper to the south of Zazid. It includes the settlements of Koper, Izola, Portorož, Sečovlje, Šmarje, Sočerga, and Rakitovec.

The mixture of Šavrin dialects proves the closeness to the Čakavian dialects, and the Rižana sub-dialect is entirely Slovene. There are many Romance loanwords in both sub-dialects linguistic legacy, mostly Venetian, Trieste-Romance, and Italian.

Why do locals speak Italian?

As previously explained in the second paragraph of this article, Croatians in Istria speak Italian because it has been implemented in public speech and institutions for such a long time.

As Marija Črnac Rocco, head of the Rovinj City Council office, explained for Novosti portal, the Italian national minority in Istria (and certain other Croatian parts) is autochthonous, meaning that the Italian component has always lived and existed in these territories.

Likewise, Italian was the official language during all the various reigns in Istria until the end of the Second World War – the Venetian Republic, the Kingdom of Austria, Napoleon's rule, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, and the Kingdom of Italy.

Rovinj, Istria / Copyright Romulić and Stojčić

After the Second World War, Istria was annexed to the Federal Republic of Slovenia and Federal Republic of Croatia, namely the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The Italian national community's position, which became a minority in a significant part of Istria due to sad post-war circumstances, has been the subject of consideration and securing the rights of many international agreements.

Therefore, the equal use of the Croatian and Italian languages in Istrian County and many towns and municipalities in Istria is undoubtedly a legal obligation, which for most Istrians is both a moral duty and a civilizational achievement of which they are proud.

Bilingualism in Istria is not only lived in translated official documents, it is lived in families, on the street, in everyday communication, in traditions, and customs. Bilingualism in Istria is natural, spontaneous, and it is perceived as an advantage and a richness.

Istria in Italian and Croatian: some important bilingual place names

Istrian County has ten cities and 31 municipalities. When you drive through Istria, you will notice bilingual traffic signs, including both Croatian and Italian names of towns and municipalities, such as:

- Buje – Buie

- Buzet – Pinguente

- Fažana – Fasana

- Grožnjan – Grisignana

- Labin – Albona

- Medulin – Medolino

- Motovun – Montona

- Novigrad – Cittanova (d'Istria)

- Pazin – Pisino

- Poreč – Parenzo

- Pula – Pola

- Rovinj – Rovigno

- Umag – Umago

- Višnjan – Visignano

- Vodnjan – Dignano

- Vrsar – Orsera

- Žminj – Gimino

As such, in Croatian, we say Istra, and Italians say Istria.

When was Istria a part of Italy?

Istria was a part of the Kingdom of Italy after the First World War when the Austro-Hungarian Empire disintegrated. In 1920, with the Rapallo Peace Treaty, Istria, the Croatian city of Zadar, as well as the islands of Lastovo, Cres, and Lošinj, belonged to Italy. Rijeka belonged to Italy in 1924. During the Second World War, the population organized a movement of resistance to fascism by Benito Mussolini. Therefore, after the war, Istria became part of Yugoslavia, where it remained until its disintegration in the early 1990s when the Istrian peninsula was divided by Croatia and Slovenia.

During the 19th and the first half of the 20th century, a significant Italian linguistic and ethnic community in Croatia mainly concentrated on the west coast of Istria and in Rijeka, Dalmatian, and Kvarner towns. After the First and especially after the Second World War, most Croatian Italians emigrated to Italy.

Grožnjan / Copyright Romulić and Stojčić

Today, almost three-quarters of all Italians in Croatia live in Istria County. The only municipality in Croatia where Italians make up a relative majority is Grožnjan in Istria, with 39.4 percent ethnic Italians in the population and 56 percent of the people whose mother language is Italian.

The Italian community's position and rights are guaranteed by the Constitutional Law on Human Rights and the Rights of Ethnic and National Communities of the Republic of Croatia, as well as various international agreements and treaties.

To follow the People Also Ask Google about Croatia series, click here.

Slavonia Students Spot 300 Spelling Mistakes In Names of Public Places

November 21, 2020 - How difficult is it to learn Croatian? Slavonia students from one high school learned it's really not so easy for people to correctly use their own language

How difficult is it to learn Croatian? Well, it's pretty difficult. Croatians know this best of all and will be reasonably impressed if you make any advances in trying to speak their language. A professor of linguistics from Zagreb University once told this writer that to be able to regard yourself as wholly proficient in the Croatian language, you would have to study it to no less than university level. Naturally, not every speaker of Croatian has done so.

Slavonia students from a high school in Slavonski Brod were recently tasked with looking for mistakes in the use of Croatian language in public places. So complex is the Croatian language, spelling and grammar mistakes are commonplace. The teacher assigning the task, Vesna Nosić from Matija Mesić high school, was no doubt confident her students would uncover some mistakes. However, the grand total of 300 spelling and grammar mistakes the Slavonia students found is possibly more than was bargained for. Particularly as those found were all assigned to public places. Matija Mesić high school in Slavonski Brod, where Slavonia students made their findings © Matija Mesić high school

Matija Mesić high school in Slavonski Brod, where Slavonia students made their findings © Matija Mesić high school

The misspelling or incorrect translation of food items on a restaurant or tavern menu is a regular cause of amusement in Croatia. But, the mistitling of public places - streets, squares, companies, monuments, traffic signs and even schools – is perhaps more surprising. These are places you walk past every day.

The Slavonia students were given the high bar of the official standards of Croatian language set by the Institute of Croatian Language and Linguistics. Their teacher, Vesna Nosić, has published their findings in the popular science journal Hrvatski jezik (Croatian language), which is published by the institute. Croatian language is something of a national obsession in Croatia, its acceptance as the official language very closely linked to the country's struggle for autonomy. For most of its history, the lands of modern-day Croatia were controlled by empires for whom Croatian was not their language. The use of foreign tongues has been imposed on the population of Croatia for centuries.

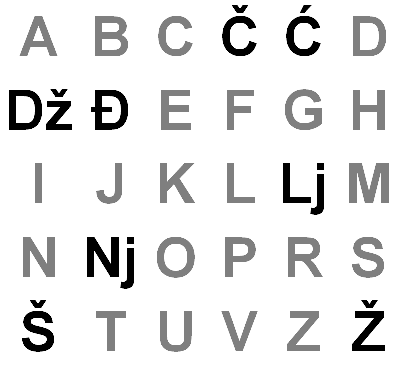

The most common mistakes made in the Croatian language are related to the incorrect use of the sounds ć and č, đ and dž. The letters here come from Gaj's Latin alphabet, devised by Croatian linguist Ljudevit Gaj in 1835. It is the Latin script used across the region in which to write the similar languages of Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, and Montenegrin (in Bosnia, Serbia and Montenegro, the Cyrillic alphabet is used as well as Gaj's Latin alphabet).

The contemporary version of Gaj's Latin alphabet (it originally contained Dj, which was replaced by đ. This alphabet ihe easiest part of learning Croatian - within 15 minutes, almost anyone can correctly pronounce all Croatian words by using this. In comparison to the Latin alphabet used by English speakers, the letters q,w,x,y are omitted. Instead, we get the additional č, ć, dž, đ, lj, nj, š and ž. Looks difficult? It isn't. Almost all of these sounds exist within the English language. Except for lj which, to English speakers, is torturously missing some kind of vowel © Albatalad

Mistakes between the ć and č or đ and dž sounds are understandable if you can pronounce Gaj's Latin alphabet. And anyone can. The easiest part of learning Croatian is Gaj's Latin alphabet – all of the sounds exist within the English language, all of the letters are always pronounced in exactly the same way (unlike English). The difference in sound between ć and č or đ and dž in spoken Croatian is difficult to perceive if you are not a native speaker (often, even if you are!)

Some of the mistakes found by the Slavonia students are perhaps more forgivable – the standard of Croatian their comparisons was made against is rigid. Thus, pekarna (bakery) instead of pekarnica, or dućan (shop) instead of trgovina were classed as mistakes, but are actually in everyday use on streets across Croatia.

Other mistakes found relate to grammar, spelling and the misuse of upper case or lower case lettering. For instance, Ulica Pavleka Miškina should be written Ulica Pavleka Miškine (the word ending changes to denote it is the street of Pavlek Miškina), Crkva Gospe od brze pomoći, should be crkva Gospe od Brze Pomoći; Muzej Brodskog Posavlja should be Muzej brodskoga Posavlja and Šetalište Braće Radić should be Šetalište braće Radića (denoting it is the promenade of the Radić brothers). Not sure which words should be in upper case or lower case in Croatian? Write everything in upper case - problem solved! © Slavonski Brod Tourist Board

Not sure which words should be in upper case or lower case in Croatian? Write everything in upper case - problem solved! © Slavonski Brod Tourist Board

Sitting to one side and watching how others do something, judging them, then informing them they are doing it incorrectly is not the most pleasant way to occupy your time. However, for the purposes of this study, this not-uncommon activity in Croatia is exactly what was asked of the Slavonia students. However, as noted in today's coverage of this story in Index, there is a great saying in Croatian that serves as a response to any unwanted judgments coming from those on the sides - “clean up the trash in front of your own doorstep before you discuss that which lies in front of your neighbour's”. And, that's exactly what the Slavonia students did – and found out that the name of their own school was spelled wrong.

Jebiga - the Ultimate Glossary to Croatia's Best-Loved 'J' Word

March the 12th, 2020 - One Croatian word seems to consistently take precedence over all others. Meet the J word and all of its wonderful variations, explained.

Croatian is a rich language and what makes it stand out from many other languages is that swearing isn't looked down upon in the same way as it is in let's say, German or English. When an English person swears, his argument is immediately seen as lost and the person saying it is immediately considered to be less intelligent. It's not the done thing if you're wanting to get your point across and be taken seriously.

In Croatian, however, while swearing still isn't exactly celebrated, it isn't given as much negative press. Often seen as a sign of passion when in an argument or when explaining something to someone, it can light up a conversation and make it more relatable, human and emotionally engaging for the listener. Jebiga and all of its variations, are words that anyone who has spent any length of time in Croatia will more than likely have heard (and multiple times). This is one such fluid, versatile word that you can insert pretty much anywhere, about pretty much anything.

Jebiga, or more politely put - the J word - is to the Croatian language what chicken is to the meat world. You can basically do anything with it. Let's have a look at this Croatian word and all of the ways one can employ it.

Zajeban - When something is malignant, evil, wicked or otherwise entirely unwelcome.

Zajebano - You can use this when describing a situation that is complicated, or better to say f*cked up.

Zajebao je - Something has been f*cked up. Used when a mistake has been made or when something has gone wrong.

Zajebao me - You can use this when someone has betrayed, fooled or in some other way deceived you. In English the equivalent would be that someone has f*cked you over.

Zajebancija - This is used when something is a joke or not meant to be taken seriously. The English would be f*cking around.

Najebati se - Torment of some kind.

Jebada - Stress or pressure of some kind.

Sjeban - If something is improper, incorrect, faulty or in some other way no longer of use or is otherwise incorrect. In short, when it's f*cked up.

Sjebao me - Something f*cked me up. It did me wrong. It brought me harm.

Izjebao me - If someone has used you or done wrong to you in some underhand, sly way, you can use this. You could also say this when someone has f*cked you over.

Jeben - Interesting, amazing, mind blowing.

Jebeno - Extremely interesting, amazing, mind blowing.

Jebenica - The thing you're referring to is amazing, perfection without fault.

Jebeni - Cursed.

Jebeš to - Literally: f*ck that.

Jebeš mi sve - That's unbelievable/shocking/there's no way.

Jebi se - F*ck off if you're saying it angrily. You're great if saying it sarcastically and positively. This one depends on tone and context more than anything.

Jebote - Oh my God! No way! You're kidding! Wow. Damn. Jesus. This particular J word has many a meaning.

Odjebi - F*ck off, get lost, p*ss off, get out of here.

Odjebati - To drop something, to no longer bother with it, to leave it alone. Or to f*ck it off.

Odjebao me - Rejection. They rejected me.

Jebački - Typically used to describe something very strong that appeals to you.

Jebanje - Being bothered, abused, tortured or otherwise irritated to some extent by something (or perhaps someone). Or if you mean it in the absolutely literal sense - sexual intercourse.

Uzjeban - Upset. Disturbed. Unsettled or troubled by something.

Razjeban - Damaged beyond economic repair or destroyed.

To ne ide da ga jebeš - When something is impossible. When it just won't ''go'' the way you want it to or the way it is meant to.

Dobar da ga jebeš - Undoubtedly good/Excellent.

Jebi me ako nije tako - Well f*ck me if it isn't so! I'll eat my hat if it isn't so. Used when you're sure something is absolutely as described.

Nemoj me jebat - Don't f*ck with me. don't believe you! Don't bother me with something.

Ne jebem te - I'm not listening to you. I'm ignoring you. I don't f*ck with you.

Jebemu - Oh, f*ck, what a shame/pity.

Nenadjebiv - When something is unbeatable.

Nadjeban - When something has been beaten.

Jebozovan - Physically attractive.

Nedojeban - Frustrated, usually emotionally.

Jebivjetar - Used to describe someone who is lazy and adopts a ne da mi se/I can't be bothered attitude.

Vukojebina - Some far-flung wasteland. Often used by people living in cities to describe small villages or other out of the way locations.

Jebiga - F*ck it.

We hope this helps you out in your next conversation. One or more of these words will help you to learn to swear like a Croat, learn more about Jebiga here. Follow our lifestyle page for more.

Croatian Customs: Jeste za Jednu Kavicu? Fancy a Coffee?

Gospođo, nešto Vam curi iz torbe! / Madam, something's dripping out of your bag! – a nice older lady addressed me that rainy cold morning just a few days ago as I was dragging myself into a crowded tram desperately trying to get people’s elbows out of my back.

For a moment or two I was living in hope that she was talking to someone else, but a quick look to a steaming-hot, black liquid dripping on the tram floor through my bag soon convinced me otherwise. I rolled my eyes and panicking tried to reorganise the contents of my bag but as the tram suddenly pulled away, the entire content of my coffee-to-go cup spilled down my jeans.

And then I realised, in that exact moment, standing in a tram with a huge coffee stain on my light blue jeans, and coffee dripping from my leg while raindrops were slowly dripping on the tram window, that I had a whole day of lecturing to people in the classroom in front of me. Okay, this is it. You've now officially hit rock bottom with your coffee addiction, I thought to myself.

It wasn't actually supposed to look like that, this morning. I was supposed to get up, get dressed, do my morning workout, prepare a nice, healthy fibre rich breakfast and then enjoy one of my favourite moments of the day - the peace and quiet with my first cup of steaming, black coffee.

Things went wrong when I slept through my alarm, I think. You see, yesterday evening I needed to get some paperwork done, so I had just a bit, well a cup, okay, maybe two cups of coffee, just to keep myself awake. So when I finally woke up that morning, I realised I had no time for aerobics, a fibre rich breakfast and rest, but to find some clothes, get the kids out of bed and make myself some coffee to go! Not necessarily in that order, I'm afraid.

In my own defence, however, if you've ever been to one of my early lessons, when I hadn't had my first coffee yet, you'd probably realise why it's essential for me to carry coffee cups around ewith me in my purse!

Thank God half of the students in the room are still sleeping through their morning lessons, so they're not paying any attention to the nonsense that I ramble on about without my caffeine kick!

A passionate approach to everything connected to black coffee actually runs in my family.

A legendary story involves my aunt Branka or teta Branka. Teta Branka is a very tall and strong red-headed woman, and a passionate coffee lover, by occupation, she's a nurse. You know how these people who work in the health care system tend to sometimes be the most stubborn patients? Well, teta Branka was no different. Once she was feeling really ill, with a high fever, a serious cough and was unable to get out of bed that morning. Her daughter came to take care of her.

''Do you need anything, anything at all?'' she asked her.

''Nothing... thank you I'm fine, I told you!'' teta Branka coughed in response, adding that there was no need for her to have come.

''Mum, you're trembling, we need to get you to the doctor!'' her daughter stated in a concerned manner.

However, teta Branka was determined she wasn't going to see any doctor, despite her shivering and coughing.

''Can I get something for you then, before I go to work?'' her daughter asked.

''Nothing'' coughed teta Branka, until she stopped and said... ''Oh, wait ...just one thing...''

Her daughter asked if she needed some tea, perhaps a warmer blanket...

''Please... if you you can just get me... samo malo crne kave / just a bit of black coffee!'' teta Blanka uttered with a broken voice.

I'm aware that all around the world people are in love in this dark hot liquid that, as the legend says, was found by coincidence, when some shepherd in a land far, far away let his goats eat some berries. The goats stood up late partying all night long, and the rest is history.

But, there is a certain special connection between Croats and coffee. I'm not just talking about all the business meeting taking place in local cafes, or those people with huge sunglasses sitting for hours and hours over one cup of coffee on one of Zagreb's many little squares just enjoying the sun. I'm talking about a real coffee ceremony that takes place in these parts.

Growing up in Croatia, some of the first scenes from your childhood involve a bunch of people gathered around the table, around a little steaming coffee pot with a tail. Usually that image is accompanied with the jingling sound of little spoons and cups, and you just knew that meant that it's coffee time. Some nations have their tea time, some have whole ceremonies developed around a simple action such as drinking a cup of tea. So why wouldn't we have coffee time here in Croatia? Well, we do. But it seems that in Croatia, any time is coffee time.

In the morning, after breakfast, before lunch, after lunch, in the evening, any time a visitor approaches your doorstep, it's time for coffee.

Being a kid, I thought that this coffee drinking ceremony was wrapped up in some sort of great secrecy. Women sitting around the coffee table would hold their cups, their heads would get closer to each other, they'd lower their voices, whisper and giggle occasionally. I would try to get closer to hear the conversation and be a part of this great coffee conspiracy ceremony, and ask if I could drink just a little bit with them, but my grandma would just look at me and yell: ''Children aren't allowed drink black coffee! You'd grow a tail on your back!''

I didn't believe her one bit. None of them had tails, and as far as I could see, they were drinking gallons of coffee every day.

At the age of 10, they realised that we weren't really buying this whole tail story and they'd usually ask you if you wanted to join them for a cup of coffee.

And, well.. everything else is history.

My grandma was from Bosnia, where the whole coffee drinking ceremony was even more developed. It included pretty little cups called fildžan, cubes of white sugar, little spoons and of course, fildžan viška, an extra cup put on the side of a tray for an extra guest who might just pop for a cup of coffee that afternoon.

I know a lot of coffee admirers in this country, but one of these is absolutely my sister. She can literarily drink coffee at any time of the day. The story goes something like this. She comes for a visit with her kids and mum at around 19:00.

''Coffee, anyone?'' I ask.

''Oh, no, I couldn't! I had five already today!'' my sister says.

''Five? Are you insane!? You need to stop drinking so much coffee... It's not good!'' mum retorts.

''It's seven... but shhh! Don't tell her, she'll go crazy!'' my sister whispers to me behind mum’s back.

The culture of drinking coffee in Croatia can mean having an espresso by yourself in a local café. It can mean starting and ending every business meeting with the question: Jeste za jednu kavicu? Fancy a coffee? Or drinking coffee to go on your way to work. We adopted that culture along with so many things from Western culture.

But, enjoying a cup of coffee in Croatia generally means that someone will take out that funny looking coffee pot with tail out from the kitchen closet, that maybe they'll bake the coffee for a few minutes, then pour steaming water over it, that they will serve all of this in some nice cups, maybe they'll even put that extra cup on the side and get involved in some serious, interesting, meaning of life type conversation, or a highly confidential conversation which usually starts with the words: Između nas... Just between the two us... making that special bond between the two people built on trust, the scent of coffee and the steam from those little cups.

Because that's what coffee in Croatia is really all about.

Language, School and Friends - What Life is Like for Teen Expats in Zagreb

It's true Croatia may not pose the most favourable conditions for young adults looking to get out into the world and establish themselves.

As funny or unusual as my story may seem, it's met with confusion and shock for good reason. On the other hand, families and younger teens and children who move over here are generally supported and understood. It’s not so out of the blue or strange to want to bring and raise your family in Croatia, with playgrounds and green spaces a mass, low crime and a good school system. In an effort to combat the mass exodus of Croatian citizens, the Croatian government even grants allowances per newborn to encourage families which, in the town of Sali for example, can reach up to 10.000kn per newborn (feel free to read more here).

The short version is simply the fact that Croatia places a high priority on family life, but has this translated into the lives of the expats kids who move here with their family?

Before me, my younger brother (we’ll call him Filip) was the first to move here. Plucked out of school in England at the start of Year 8, Filip had just begun high-school in the UK. After a difficult time and a lot of change since then, he now finds himself studying and socialising at a local Croatian school in a small town not far from my parents village. Here is what he has to say about the experience...

“It was a very stressful and difficult change to make, I had a little bit of excitement but was afraid of everything, of having to get to know this new country as I had no idea what to expect really”.

I asked him if he was most afraid of having to make new friends, “nope” he responded as if that was a dumb question to ask.

“Really?, not at all?”

“No, I mean you just get on with it, that wasn’t the scariest part”.

We continued our conversation about friendships and connected on the limitations of the language barrier. Understandably, his main advice for those deciding to move to Croatia would be to have some knowledge of the language beforehand, even if just basics.

“It’s easy to make friends, everyone is pretty open and friendly and there will always be those that are fluent in English, but not everyone speaks English well...without some Croatian, it limits who you can talk to and there’s not that same connection as you would have with people who speak your own language”.

We chuckled at this point, and I definitely agree with him. You can always have friends and be courteous with each other but making a real connection is the tricky part. The language barrier does end up limiting your social circles and what you can get up to no matter how outgoing or positive you might be. Sitting at a cafe table with a group of our Croatian colleagues one time, my expat friend from Australia joked that “we have that Western understanding” and it’s very true.

Don’t let that discourage you though. My brother, now coming to the end of his second year at a Croatian school, says he’s very happy and wouldn’t change how things are.

“While we’re in a small village there isn’t much to do except hang out at the cafe bars or at each other’s place, but we always find something to get up to. In Zagreb there’s a ton of things to do”.

From most of the kids I’ve spoken to language wasn’t a central issue. While daunting, they managed to pick up Croatian pretty quickly and the majority of their peers spoke decent to fluent English so communication wasn’t hard. The teachers were supportive and keeping up with the classes was a challenge but not impossible.

On the other side of the spectrum, I also spoke with two wonderful girls, Nina, 16 and Marica, 14 who moved here from Australia. They both arrived with some understanding of the Croatian language, so their experience settling in was a little different as well as their initial fears.

Before the move, Marica recalls worrying what the Croatian kids would think of her, if she’d be able to build friendships and easily fit in. While her older sister Nina, was excited for the move saying she was looking forward to something new and a totally different environment. Once here, their experience of adjusting to life in Croatia continued to be polar opposite, but not in the way anyone expected.

As she arrived aged 13, Marica was able to start a regular Croatian state school in their town just outside of Zagreb. She had a ton of support from the state and her school, spending the first semester entirely dedicated to getting adjusted to the new system and focusing on language learning - which amounts up to 70 hours of Croatian all funded by the state. Over time, Marica found herself settling in easily and starting up a new social life. I asked if she'd consider staying in Croatia or if she has any desires to move back to which she responded cheerfully that, she’ll give it a go [in Croatia].

Nina, being much older, found the move more challenging and was launched into the intense IB course at an International school in Zagreb. Nina found the support was much more limited compared to her younger sister, and has had a more challenging time connecting with her also foreign peers given the intense curriculum, competitive academics and social divides.

Overall, both sisters as well as parents can agree that school and life abroad can reap many universal benefits, from confidence to a well rounded worldview. But with regards to Croatia, both advised to not set high expectations on life here. Go with the flow, and adapt to the culture instead of trying to change it or comparing to life before was the takeaway.

It’s fair to say the benefits of studying and growing up in Croatia are no more apparent than doing so in another European city, however, families can rest assured there is a ton of support from other expat families, the government and schools if they do decide to come to Zagreb or Croatia in general (checkout the expat parents in Zagreb Facebook group for a start!).

It’s reassuring to know a stable social life is more or less easily attained as well. In line with my brother’s experience, I heard over and over that coming younger makes adapting, school and language learning easier. It also opens up more options, since particularly in Nina’s case she had to go to an International School to finish her studies as the Croatian system was too different for her to jump into.

At the end of the day, I can only commend my brother’s as well as Nina and Marica’s brave dive into a new culture and the way they've managed to transform the experience into something positive at such a younger age, and I can only hope the experience continues to shape them as well as encourage others to experience life in a totally new environment (whether in Zagreb or elsewhere!)

Please note that the names mentioned in this article have been changed for the sake of privacy

Interested in more about life in the capital? Give Total Zagreb a follow. For more from Mira and her experiences, follow her here.

Croatian Mondays - Speaking, Talking, Telling and Saying

Croatian Mondays - Molim, Hvala, Izvoli, Oprosti

If you're trying to learn Croatian, you will probably realise that Croatian language, as beautiful as it is, can represent quite a challenge and a daily struggle with its often unpredictable and various changes. So, we asked prof. Mihaela Naletilić Šego, a Croatian language teacher from the Croatian language centre CRO to go, to help us help you out with the little secrets of the Croatian language.

Molim? Hvala! Izvoli! Oprosti!

Prodajemo karte za tramvaj – This was handwritten with a black marker on a wrinkled piece of paper and taped to the glass of the little news stand which I was approaching that cold Wednesday morning a couple of days ago.

I was just about to open my mouth and ask: Oprostite, imate li karte za tramvaj? Excuse me, do you sell tram tickets?

But then I spotted that sign, so instead I just said:

- Jednu kartu, molim Vas! One ticket, please!

- Izvolite! There you go! – said the sales lady.

- Hvala! Thanks! – I replied – Oh, and you have a nice sign! – I smiled at her and wanted to leave, but that little sentence opened up Pandora's box.

- I know! – the sales lady was obviously very upset – Can you believe every f*cking five minutes a person comes up to the f*cking news stand and asks me if I sell f*cking tram tickets!? Well, why don't you ask me for the f*cking ticket and i will I sell it to you if I have it! I mean it's just f*cking unbelivable! – she was yelling and frenetically waving her hands.

- Oprostite što sam nepristojna! I'm sorry I'm being so rude ! Hvala što ste me saslušali! Thank you for listening to me! Have a nice day! - she suddenly realised that she was talking to a customer, fixed her hair a bit and closed the little window in front of her.

It was nice of her to apologise, but in fact, if I put aside the swearing and yelling, she was actually quite polite and used all the little important polite Croatian words:

Molim? - I beg your pardon?

Izvoli! - Here you go

Hvala! - Thank you

Oprosti! - Please forgive me or excuse me

Lijepa riječ otvara i željezna vrata. A nice word opens even iron gates, as one nice Croatian saying would advise us. It might open the iron gate, but it certainly doesn't open the gates of – Croatian bureaucracy!

I realised that one rainy January morning when I tried to get some information on the parking ticket that I'd received, by using – a telephone. You know, a telephone, that fancy new gadget that Alexander Graham Bell invented recently in order for people to get information they need by using a wire instead of walking to the other part of town on rainy Monday mornings.

I sat down that morning and dialled the Information centre of the city office.

- Molim? Yes? - A tiresome and utterly bored female voice answered my call somewhere in the wasteland of the city office after the phone rang for aproximately 45 times.

- Yes, hello - I opened my mouth enthusiastically - I wanted to get some information about the parking ticket I received...

- Gospođo, Madam - the voice said slowly - You can pay your parking ticket in any bank or you can do it here in person…

- No, no, no, I don't want to pay it, i just need some information…

- Where would I be if I gave out information to every person that rings here? asked the bored voice, interrupting me.

Erm… in the information office, I thought to myself, but out loud I just took a deep breath and said:

- Could you put me through to someone who can give me the information that I need?

- Of course. You should have said so in the first place, the bored voice replied utterly apathetically.

- Hva… I wanted to say thank you, but a sudden loud sound interrupted me.

La la la la. la la la. Ah, its Tchaikovsky, symphony No.3.

I was just about to fall asleep daydreaming to the nice music, when I finally got connected.

- Dobar dan! Good day!

- Yes, hello – I began happily - I was so happy I finally reached someone who I can ask…

- You reached the talking machine of the city office – the voice goes on - for citizen's advice call on work days from 13:00 until 14:00...

I checked my watch. It was 08:15. So I redailed Miss Bored Voice and firmly decided to be a bit more tough with her this time!

La la la la. La la la. La laaaaa....

- Dobar dan! I want to talk to someone about my parking ticket, I don't want to pay it, I don't want to be put on hold and I don't want to talk to a talking machine and if you don't connect me to someone this second, I will…

- Nema problema, gospođo! No problem, Madam! – the new, male voice said - Samo polako! Take it easy!

- What do you mean, nema problema? – I asked with absolute mistrust.

- I will put you through, replied the voice

And so he did.

La la la la. La la la. La laaaaa...

- Moooolim! Hello! - a fluttery soft voice twitted to my handset a few seconds later - How can I asist you?

- Oprostite, sorry, is this still the city office?

- Yes, of course! Izvolite? What can I do for you? - This new, fluttery voice was music to my ears.

In the next few seconds I explained my parking ticket situation to the nice lady with the fluttery voice.

- Let me see what we can do about it. I'll check on my computer.

- So, I don't have to go down there in person? - I asked the nice lady rather timidly.

- Molim Vas! Oh, Please! Why should you have to? We're all connected now you know! – she laughed candidly to me.

- However, I am with a client now, so if you could please just call back in ten minutes, we will solve your problem!

- But wait! Who should I ask for? - I yelled down the phone frantially. Too late. She was gone. Still, I waited politely for twelwe minutes and called the nice lady again.

La la la la. La la la. La laaaa...

- Molim? Yes? - Miss Bored Voice phlegmatically answered.

- Yes, I just called ten minutes ago and your colleague connected me to the lady who…

- Oh, it's you again - Miss Bored Voice sighed. What colleague? I don't have a colleague. I work alone.

- Well, maybe a ghost connected me then, how do I know? - I was getting a bit tired of this whole thing at this point, but Miss Bored Voice showed no reaction to my open provocations.

- Wait a minute - she sighed again.

Miss Bored Voice was obviousley on to something now.

- Maybe the doorman answered the phone while I went for a glas of water. My tooth hurts like crazy. Joooža! Jooooža! Did you answer the phone?! - Miss Bored Voice yells.

I could hear the poor doorman Joža minding his own business and just shrugging his shoulders all the way across town.

- Gospođo, Madam, the doorman doesn't have a clue about any nice lady who gave you any kind of information. Hold on, I have another call. I'll put you on hold...

- No, no, don't put me on hold, I just need to talk to the nice lady!

La la la la. La la la. La la. Tchaikovsky. Symphony No. 3.

- Yes, Mirjana, yes - I could hear Miss Bored Voice geting much more excited about a cake recipe after some ten minutes of listening to the wonderful but repetitive Tchaikovky - Just put the flour in before the eggs, that's the trick! Hahahahah yes, yes, what can you do! A kako je Damir? How is Damir? Pozdravi ga! Tell him I said hi!

- Molim? Yes? - she said as she finally addressed me - Oh, it's still you... - the voice sounded pretty disappointed that I was still there.

And then I snapped.

- Look here, I had enough of this treatment. I want to talk to your supervisor this minute! - I screamed at her.

- Well good luck with that! I've been wanting to talk with him for days about my overtime working hours - I could even feel Miss Bored Voice smirking slyly over the phone.

- I'm not joking! - Now I was yelling. Put me through to your supervisor this minute!

- Nema problema gospođo! Izvolite! No problem, Madam! Here you go!

Of course, I was greeted with Tchaikovsky and symphony No.3 once again.

If you happen to see (or hear) the nice lady with a fluttery voice from the city office, please tell her I said hi!

If you want to learn more about Croatian language courses, click here.

Croatian Mondays - How Are You? Kako Si?

If you're trying to learn Croatian , you will probably realise that Croatian language, as beautiful as it is, can represent quite a challenge and a daily struggle with its often unpredictable and various changes. So we asked prof. Mihaela Naletilić Šego, Croatian language teacher from Croatian language centre CRO to go, to help us help you out with the little secrets of the Croatian language.

Kako si?

A wise man once made an excellent remark on Croatia and Croatian people after spending some time here: Croatia is such a beautiful land, but I have never seen as many sad looking people on the streets as I did in Croatia.

If you ever took a ride in one of Zagreb's blue trams you might wonder: Could these worried and agitated looking people with mobile phones in their hands be the same shiny happy people laughing and simply glowing from the photos posted on social networks?

If you look at it in general – as a nation - we carry around a big grey cloud of constant dissatisfaction over our heads. We did experience a short period of blissful and unspoiled national hapiness this summer during the World Cup, though!

In that short period of time, everybody was grinning on the street for no reason whatsoever, drivers weren't swearing at each other, mums weren't yelling at their children on playgrounds and there were a lot of random happy faces on the streets of Croatia.

But those days seem long forgotten now, and we just went back to being the unsatisfied nation with that big grey Croatian – nothing is good in this country - umbrella above our heads! I often find myself riding in a blue tram or walking through Zagreb streets with a grey cloud filled with thoughts over my head. And then I bump into an old acquaintese whom I heaven't seen for ten years. Actually – my ex boyfriend. Who of course happens to look amazing that morning. It's obvious that he'd spent quite some time in the gym since we broke up!

Thank God I went jogging yesterday and woke up a bit earlier this morning in order to apply a ton of makeup, I thought.

- You look great! – he says.

- Thank you! – I reply politely and twinkle my eyes.

- The same as when we were at college! – he goes on.

Well, he was always a bit of a compulsive liar, now that I think of it. And then he pops out the eternal question: Kako si? How're you doing?

How might one reply to the most commonly asked question in the world when its your ex boyfriend, whom you haven't seen in a decade, asking, one might wonder? While I was thinking about what reply I could give to absolutely dazzle him, I started to wonder how Croats approach this eternal question. There are a few possible answers you might get when you ask about other poeple's lives in Croatia.

The complete and noncensored life story. Some people just don't realise that kako si? is asked out of courtesy, and simply get an urge to tell you their entire life story. A bit like my neighbour.

- Kako ste, susjeda? How are you, neighbour? – I would ask her while heading to my work.

- Oh, I have been fine lately, thank you for asking! – she smiles happily to me.

- Good, I'm glad! – I reply quickly and start to move my feet since I'm already a bit late for work.

- Nice to see you! – I try to turn my back and wave a bit to her to say goodbye.

Try is the key word in this sentence.

- But you know what happened to us just last month? - she gently but decisively grabs me underneath my arm – Do you know that we had a burglar at our cabin in the mountains?

- Yes, that's very nice, I'm glad for you – I'm obviously not paying attention anymore, trying desperately to free my arm and catch that tram which is just around the corner - but I really need to go, I'm in a bit of a rush…

- Imagine the nerve of him! To barge into a house like that! – she completly ignores attempts to escape and continues with the endless burglar story, as I watch sadly how tram number 12 is leaving the tram station without me.

- Of course, we called the police – now she's yelling – But what did they do, I ask you? Nothing!

The interesting fact with these people who tell you their entire life story, is that when it's your turn to tell your life story story, suddenly they run out of time.

- A kako si ti, draga moja? And how are you, my dear? – she finally remembers that I might have something going on in my life as well.

- Well, you know… I start talking, but in that moment she experiences an instant Eureka-moment.

- Oh, no! I forgot I have to be home in five minutes to let the dog out! Nice seeing you! – and just like that, she's gone.

Nisam baš dobro. I'm not so good.

A lot of people will tell you: Nisam baš dobro. And some aren't very good at that point in their lives, and it's therefore nice that someone can listen to them and maybe make them feel a bit better. But then there are those people who are simply always dissatisfied.

- Oh, I'm not so good. You know I won a lottery last month. We bought a new car and paid off all of our debts. My daughter got a new job and we're going skiing this weekend. But, the weather is really lousy lately… This jugo (type of southerly wind) is killing me!

The weather is a huge ''mood issue'' in this beautiful country. Somehow it seems that there is always something wrong with the weather. And there is! it's so warm in the summer you have to wear short sleeves. The rain just won't stop falling in autumn and sometimes it gets so cold in winter that it actually snows. Not to mention all the wind in spring time! Ah, the wind. One of Croatia's unresolved mysteries.

Growing up in a big house in a cold and foggy little town on four rivers with my grandmother who moved there from warm and sunny Dalmatia, I soon realised that the wind is a higly important life issue. Grandma Marica was eternally worried about the weather, and the the posibilty that some day, somewhere, somehow you might just simply freeze. She was especially concerned about the wind situation.

- Put a sweater on your back, there's some nasty north wind outside! – she would often warn me. The worst enemy of all possible winds was, of course, the propuh (draught).

- Put some clothes on those children! she would anxiously yelled to my mum while our old car with no air conditioning was leaving the backyard melting in the tropical summer heat.

- You have no idea how draughty it can get on the ferry boat!

Lately I have realised that the mood of lots of Croats depends on the type of wind that is currently blowing outside. And that biometeorogical weather report every night after the evening news is certainly not helping the nationwide situation of unhappiness. You just had a great day and you're feeling happy and good about yourself and your life and then you watch the evening weather forecast.

Some very educated looking and serious looking guy tells you that the weather conditions will not be good at all tomorrow, and that sensitive people can expect headaches, dark thoughts, severe moping and in short – they will have a crappy day.

Tako – tako. So – so.

A wise and a good diplomatic answer that makes your friends interested in a discussion over a beer, and your acquintances, just a bit confused.

But, you know what the best answer to kako si? would be? Dobro sam, hvala! Good, thank you! or Odlično, hvala! Great, thank you!

Dobro sam! I'm fine! or even better Odlično! Great! – with a smile on your face. It makes your friends happy and your enemies miserable, and we sure need some more smiling faces in Croatia. After all, the World Cup wasn't such a long time ago!

If you want to learn more about Croatian language courses, click here.

Croatian Mondays - Life and Language in Croatia

If one of your New Year’s resolutions is to learn Croatian, you'll probably realise that Croatian language, as beautiful as it is, can represent quite a challenge and a daily struggle with it’s often unpredictable and various changes. So we asked prof. Mihaela Naletilić Šego, a Croatian language teacher from the Croatian language centre CRO to go, to help us help you out with some of the little secrets of the Croatian language.

Oprostite, koliko je sati? Excuse me, what time is it?

For a lot of people who move to Croatia, after a few weeks of living in their new country, Einstein's postulates on the relativity of time suddenly get a whole new meaning. That usually happens the very first time a newcomer encounters an urgent pipe problem in their household and has to call – the plumber.

That exact thing happened to my friend Anna just a few weeks after she moved to Croatia. It was one warm Sunday evening when she came home from town to find her bathroom completely flooded. Anna grabbed her phone, and quickly found a number on the Internet.

Hitne intervencije / Emergency repairs – it was written. She explained her problem to the man on the other end. He didn't seem overly impressed by her bathroom flood situation. He yawned a couple of times and just mumbled:

''Yes, yes, madam. We'll be there tomorrow morning, no problem.''

''What do you mean tomorrow?'' Anna was confused. ''My entire bathroom is flooded!''

''Gospođo/Madam, it's a holiday weekend. Tomorrow morning is the best I can do,'' the plumber replied indifferently.

''U koliko sati dolazite? What time will you be here? she asked naively.

''Gospođo, odakle da ja to znam? Imamo posla preko glave! Računajte da bi između sedam i dvanaest bi mogli biti kod Vas. Madam, how can I know that? We're up to our necks in work! We should be there between seven and twelve,'' the plumber seemed agitated.

The next morning Anna got up early, dressed up, made some coffee – and waited. And waited. And waited.

At 12:00 she started to suspect that the words between seven and twelve in fact meant between seven and midnight - and she decided to call the plumber once more. The plumber apologised and once again very vividly explained how they are fully booked and up to biiip work and biiip…

''Sutra dolazimo, gospođo, sigurno! Nema problema! We're coming tomorrow, Madam, no problem (or perhaps more accurately in English - no worries)'' he sounded cheerful and promising.

I'm not going to go on with this story, because, to be honest, I have no idea how it ended. Last time I heard from Anna, she was still waiting in her kitchen. I'm sure they will be there tomorrow, though. The plumber promised her just a few days ago!

That Monday, Anna realised that the word tomorrow in Croatia has a metaphorical meaning. It could mean a number of things, such as: later this week, sometime this month, this year, in February or in spring time… but it never, ever means – tomorrow.

Croatian is a really interesting language. You can find at least ten different words for such an ordinary thing as a ladle: grabljača, grabilica, kutljača, kaciola, palj,paljak, šefarka, šeflja, kutal, kačica…

And then you find out that Croats use one word that describes ten different things at the same time!

Let's take a look at the Croatian word SAT, for example. Sat is a word that translates to watch, as in the watch you'd wear on your wrist. Imagine you're going out with a friend in Zagreb. You are all dressed up and have your new watch/sat on your wrist. Of course, you're heading out to the main square, because your friend said:

Nađemo se kod sata! Let's meet by the clock! (Yes, sat is also a clock).

If you're meeting someone in Zagreb, that sentence most commonly means only one thing – that you are meeting by the clock on Trg bana Jelačića (Ban Jelačić square) or the main Zagreb square, or simply - Trg.

Meeting someone by the clock can get a little tricky if the person you are meeting is from Dalmatia. I've had my fair share of experiences freezing under the clock on Trg waiting for my dear friend from Split who promised to be there right on time that windy January evening. U pola sedam (half past seven). I had been standing there for at least forty five minutes until I realised that down in Dalmatia, time goes by a bit differently.

7.30 in Zagreb is pola osam (as in, half an hour to eight), while in Split is referred to as sedam i po (seven and a half). From that time, whenever I set an appointment with my Split friend at, let's say 10:30, I always doublecheck – That’s deset i po, right?

You might have noticed that Croats often say: Vidimo se za sat vremena! See you in one hour!

Although this sentence also sometimes has a metaphorical meaning, the word sat in Croatian also has another meaning – hour.

None of these sentences should create a confusion in your mind. But if you text your Croatian friend and ask him to go to out with you, it might confuse you when you get the reply: Na satu sam! I'm on the clock!

Although Croats can be a bit peculiar on occasions, I assure you that this sentence doesn't mean that that your Croatian friend is currently sitting on that main square clock we mentioned earlier just waiting for you! It does mean that they are currently in some kind of a lesson and cannot answer your question.

Na satu sam. I'm in a lesson.

And of course, if you get lost in time wandering through the many charming little streets of Zagreb while waiting for your friend, you can always ask: Oprostite, koliko je sati? Excuse me, what time is it?

If you want to learn more about Croatian language courses, click here.