Whatever you might think, graffiti are not a medium exclusive to the modern age

Whenever the subject of graffiti comes up, the discussion always comes down to a simple dilemma: art or vandalism? However you look at it, this form of, um, manifestation of creativity is thought to be a product of modern urban culture; we marvel at elaborate grandiose scenes created by local artists and ramble on about the pesky kids who have spoiled the freshly painted building facades while trying to practise their autographs.

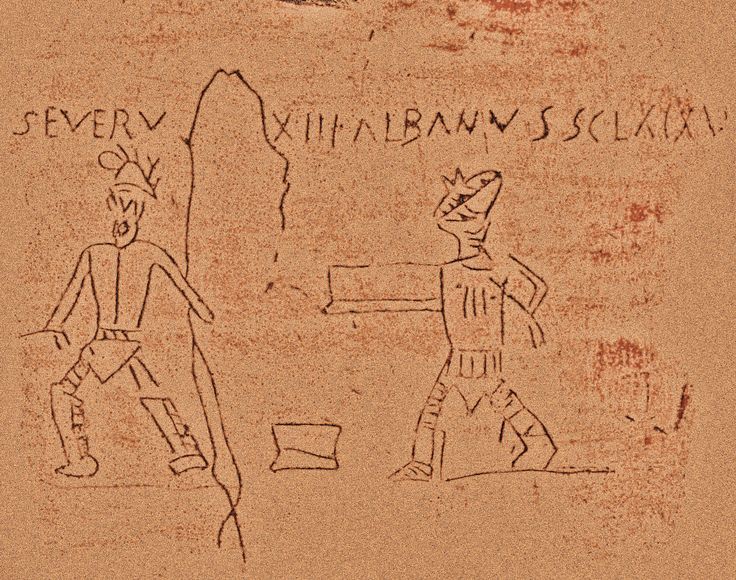

And yet, when you stop to think, you'll remember graffiti are one of the longest-living outbursts of people's internal need to communicate a message. A single look back to the ancient Roman era, and you'll find random phrases scribbled on many a historic site: Pompeii alone present a stunningly vast array of delightful inscriptions left on the walls of taverns, brothels and various public areas. For example, residents of Hvar island who had to put up with drunken tourists using their yards as public toilets this summer will identify with the following message, scribbled on the house of a certain Pascius Hermes: To the one defecating here. Beware of the curse. If you look down on this curse, may you have an angry Jupiter for an enemy. (Those who were amused by the controversy might take liking to another message found outside the Vesuvius gate: Defecator, may everything turn out okay so that you can leave this place.)

Look further, and you'll see nothing much has changed in two millennia. Kiss-and-tell maneuvres in highschool halls aren't a novelty, as some liked to brag about their (or others') romantic conquests 2000 years ago: Celadus the Thracian gladiator is the delight of all the girls, says an inscription on the barracks of Julian-Claudian gladiators. Tourists in 2017 who are annoyed with wine of poor quality served in local taverns, festival crowds despairing over watered-down beer… you're not alone: What a lot of tricks you use to deceive, innkeeper. You sell water but drink unmixed wine. Trip Advisor reviews? We have wet the bed, host. I confess we have done wrong. If you want to know why, there was no chamber pot. Pro tips from an experienced visitor? At Nuceria, look for Novellia Primigenia near the Roman gate in the prostitute’s district. Worn down by life and taking comfort in even the smallest of accomplishments? On April 19th, I made bread. The list goes on and on, bearing witness to the fact that even with our impressive tech advances, us humans haven't really changed much. We're still a cheerful, drunken bunch of flawed individuals who above all want to be acknowledged. Hey, it's me. I did this and that (and those). I was here. To quote the latest cinematic rendition of Mad Max, witness me.

To my knowledge, there are no inscriptions left in the Diocletian's palace or at the Arena in Pula, but here in Croatia, we have something equally entertaining: glagolitic graffiti in medieval chapels in Istria. Think the youth of today are vandals for scribbling their names on buildings? Try scribbling your names on church walls – on the inside. Imagine attending a service and feeling a sudden irresistible drive to produce a pen and start jotting down random thoughts on a fresco.

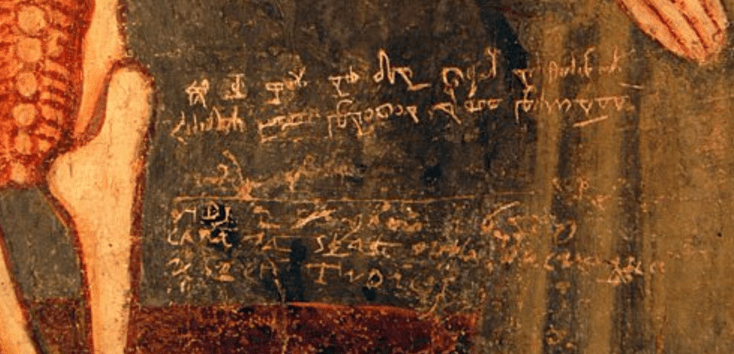

And yet, there's plenty of evidence our medieval ancestors took special pleasure in indulging this particular need. Numerous chapels in Istria bear witness to this fact: inscriptions in glagolitic alphabet carved into walls, often found on stunning works of medieval art. What might be perceived as a shameful act is actually quite amusing from a modern perspective; as with the Romans, finding out what people were troubled with in the Middle Ages makes for an interesting read, an insight into the daily life in an era that's hard to imagine.

Another thing worth considering is the scientific value of such inscriptions, vandalism or not; thanks to these quirky facts written down centuries ago, historians were able to build on their knowledge of this particular period. The graffiti also stand as evidence of literacy in these parts: the glagolitic alphabet, the first Slavic script in use, was well-spread in Istria and on Kvarner as early as in the 12th century. It wasn't a privilege of the well-educated – clergy and noble families – as plenty of inscriptions were written by a commoner's hand. Don't be mistaken, the clergy was equally to blame, with numerous bishops and priests making sure to carve their names into chapel walls.

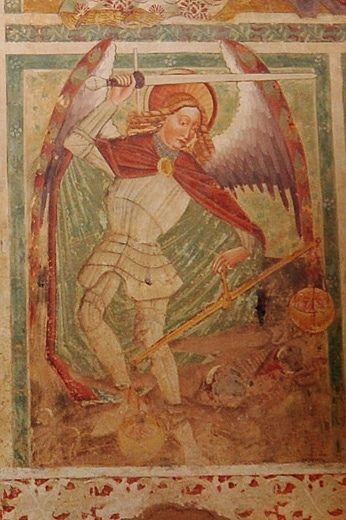

My all-time favourite inscription is to be found in the church of St. Mary at Škriline in Beram. The church is known for the extraordinary fresco cycle painted by the local artist Vincent of Kastav, but after you're done marveling at the Dance of the Dead and look closer, you'll find tiny messages inscribed at the bottom of the frescoes. The one in question is carved into the scene that depicts St. Michael attacking the devil, saying UDRI MIHO – Get him, Mike! You just have to admire the spirit.

Beram

Medieval worshipers weren't exactly preoccupied with studying the Holy Scripture to learn about the intricacies of theology – it was the visuals that helped people grasp the basic dogmas of the Christian faith. One glance at the Last Judgment, the blessed enjoying an eternity in heaven while the damned got to bathe in the fiery pits of hell, and every proper believer out there instantly knew how they were expected to behave in order to avoid getting tortured by demons. On the institutional level, art was a convenient tool for social control; on the level of everyday life, people were filled with glee at the sight of the devil getting impaled by saints. Get him, Mike!

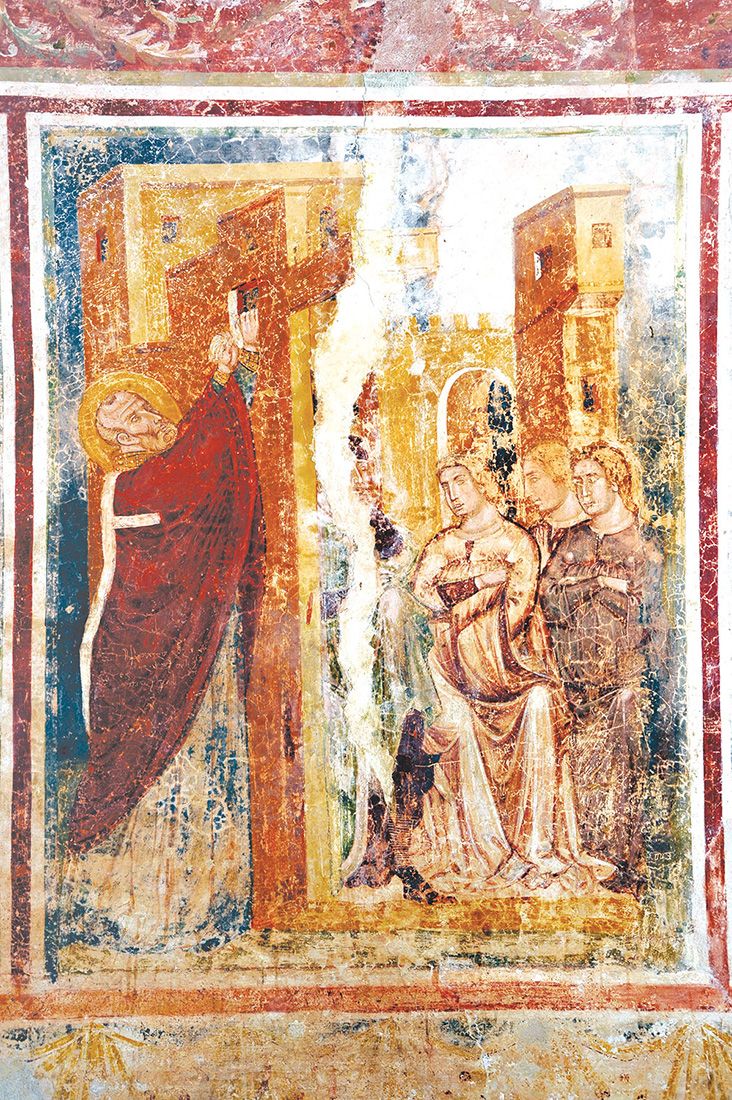

The church in Beram houses no less than 130 glagolitic inscriptions; others have been found in chapels in Draguć, Svetvinčenat, Gračišće, Pazin and Barban, to name only a few. They all speak of common social issues: people's aspirations, illnesses, poverty, war. There's a touching message preserved in the church of St. Nicholas in Rakotule, on the fresco depicting St. Nicholas leaving a bag of gold on the windowsill of a poor family's house: Give me a coin or two as well, Nico, so help you God.

Rakotule

Another inscription in the church in Draguć village bears witness to a famine in the 16th century: When Jerolim Grgurović from Draguć travelled to Grimalda in 1564, he was hungry for some wheat bread. For some humour, look to the parish church in Pazin, where the wall behind the main altar bears an inscriptions saying I, Ivan Fraščić, came to Pazin and wrote… we don't know what he wrote, but another person made sure to finish the statement: ...wrote that I'm a beast and a worthless trinket. Nice.

Beram

The man we have to thank for the majority of Istrian graffiti coming to light is Branko Fučić, a prolific art historian who used to travel around the region, spending days and nights in chapels, scratching away at cracked layers of paint that were hinting at goldmines of information hiding beneath, transcribing and documenting the incriptions on display.

All things considered, next time you spot some graffiti in town and start despairing over the youth ruining civilization, think of the medieval inscriptions and how valuable we think them today. Who knows – in 500 years' time, some historians out there might be quite thankful for our irrelevant scribblings.