25 Hilarious Croatian Place Names Explained: Big Fart to Grandma's Ass

May 11, 2023 - Would an island called Grandma's Ass be on your bucket list? A look at some of the funnier Croatian place names, and the reasons behind the names.

Which Croatian island will you visit this summer?

Hvar, Mljet, Krk, or Losinj, perhaps?

Or how about the islands of Big Fart, Little Fart, Big Whore, Little Whore, or even Grandma's Ass?

Discover 25 hilarious Croatian (and one Austrian) place names, and how many of them got their name.

The latest from the Fat Vlogger, going live at 19:53 tonight.

You can read the original article by Vedran Pavlic, which was the inspiration for this video here.

****

You can subscribe to the Paul Bradbury Croatia Expert YouTube channel here.

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning - Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

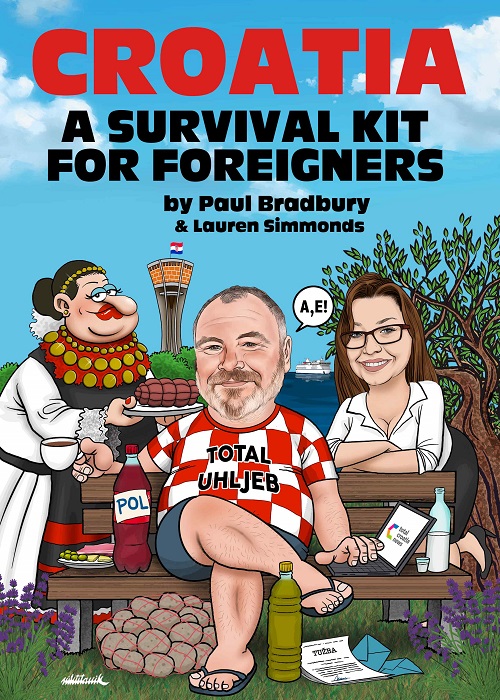

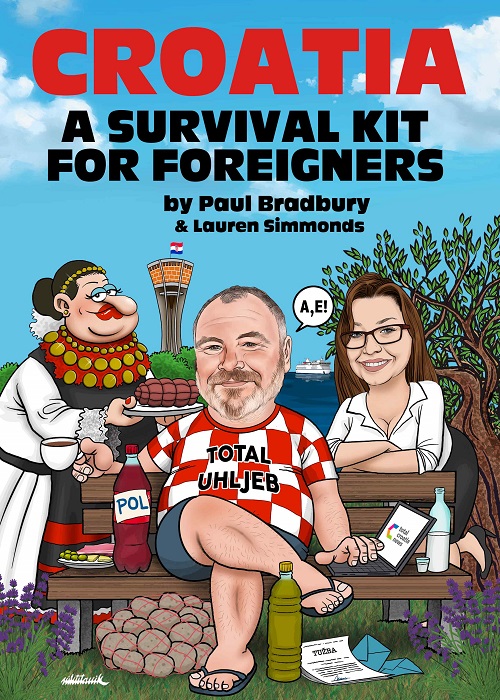

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners is now available on Amazon in paperback and on Kindle.

Exploring The Croatian Language - The Southwestern Istrian Dialect

March the 20th, 2023 - While you will likely have heard of Istrian, or the Istrian dialect, unless you're into linguistics, you may know less about the dialects and subdialects within that scope. Have you ever heard of the southwestern Istrian dialect?

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian.

Istria is known even today for being part of Croatia that has seen enormous change, and many different groups and ethnicities pass through and live on the peninsula. It's far from just the influence of Italian and the former Venetian Empire which reigns strong in this region of Croatia. For a quick linguistic example, in Istria alone, we have Istriot, Istro-Venetian, Istro-Romanian, and the extinct Istrian-Albanian. That's far from all. In this article, we'll delve a little deeper into the southwestern Istrian dialect, which is part of the much wider category of Chakavian.

A brief history of the southwestern Istrian dialect

As stated above, the southwestern Istrian dialect belongs to the group of dialects called Chakavian and contains both Chakavian and Shtokavian features. Despite this, it is generally considered to be the most widespread Chakavian dialect in all of Istria, originating not from any Italian influence, but from the dialects spoken much further south, down in the Dalmatian-Herzegovian region. If you want to get a little more complicated, this dialect is part of the Chakavian-Shtokavian/Shtokavian-Chakavian/Stakavian-Chakavian Ikavian dialect(s). A mouthful, I know, but much like with most other dialects and subdialects, linguists have butted heads in the past when it comes to proper classification.

Because of this mix of both Shtokavian and Chakavian features, most experts believe that the origins of the southwestern Istrian dialect can be traced back to what most other dialects spoken across Istria resulted from - migration. The aforementioned Dalmatian-Herzegovian influence likely draws its origins from the arrival of Dalmatian settlers from the wider Makarska area (Central Dalmatia) in Istria back during the sixteenth century.

These people primarily spoke in a Shtokavian-Ikavian dialect which still had its own Chakavian features. When more Dalmatian settlers arrived on the peninsula from a little further north in Dalmatia, more specifically from the wider Zadar and Sibenik areas, the elements of Chakavian were even further enhanced.

Why did Dalmatian settlers move to Istria?

If you're anything even close to a history buff, you'll probably have guessed the reason for this migration - the Ottomans. The Ottoman Empire and its marauding Turks were the reason for mass migration of many different ethnicities during this period of history and indeed beyond it. It wasn't just that empire that mixed things up, however, with the then extremely powerful Venice also moving different ethnicities to Istria as the decades passed owing to Istria's dwindling native population. This is the primary reason for the emergence of the now extinct Istrian-Albanian language, for example, as ethnic Albanians also settled there.

As time rolled on, different ways of speaking emerged, and people who primarily spoke Novoshtokavian dialects arrived in Istria, having themselves come from the wider Sibenik and Zadar regions. This gave rise to the southwestern Istrian dialect as it is known and accepted today, and it is considered by many in the field of linguistics to be a post-migration dialect. The overall result of this turbulent period in history is that today, in that dialect, Chakavian features mostly prevail everywhere except in the area of the extreme south of Istria, all the way down to Premantura and its immediate surroundings.

Where can I hear the southwestern Istrian dialect spoken today?

In modern times, the southwestern Istrian dialect is spoken upwards from the extreme south of the region, along the west coast of the Istrian peninsula all the way to the mouth of the Mirna river.

Heading east, the dialect encompasses the areas of Kringa, Muntrilj, Kanfanar, Sv. Petar u Sumi and Sv. Ivan, along the west bank of the Rasa river to Barban (not to be confused with Barbana in Italy!), then it encompasses the areas of Rakalj, Marcana, Muntic, Valtura, Liznjan, Sisan, Medulin and the southern part of Jadreski. The southwestern Istrian dialect can also be heard in several other small villages and hamlets.

For more on the Croatian language, including the histories of various dialects, subdialects and extinct languages, as well as learning how to swear in Croatian, make sure to keep up with our lifestyle section. An article on language is published every Monday.

Exploring The Croatian Language - The Slavonian Dialect

March the 13th, 2023 - Standard Croatian is made up of a very significant number of dialects and subdialects. From the extreme south of Dalmatia to the northernmost points of modern Croatian territory, the way people speak varies considerably. Have you ever heard of the Slavonian dialect?

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian.

Heading to the overlooked eastern part of Croatia, we find ourselves in Slavonia. This region is dominated by agriculture, and in contrast to most of the rest of the country, it is flat, making it perfect for fields as far as the eye can see. Formerly the bread basket of Croatia and indeed the wider region, Slavonia has unfortunately become synonymous with Croatia's burning demographic issues which have since spread across even the more economically favourable areas.

Much like almost every other part of Croatia, Slavonia has its various dialects and subdialects. In this article, I'll stick to the basic Slavonian dialect before delving into deeper specifics surrounding subdialects.

Where is the Slavonian dialect spoken?

The name certainly gives this one away - in the eastern part of Croatia. First and foremost, the Slavonian dialect is sometimes called the Slavonic dialect and is a dialect of the far wider Shtokavian, one of the three main dialects making up standard Croatian language as we know it today. It boasts numerous more archaic features when compared to other dialects based on Shtokavian and is spoken by ethnic Croats who come from various parts of Slavonia. As a marginal western Shtokavian dialect, the beginning of its linguistic development looked starkly different to the end result, it was also spoken in more areas than it is today.

A brief history of the Slavonian dialect

Ways of speaking that belong to the wider Slavonian dialect have been being spoken to varying degrees in the extreme northeast of parts of the country in which Croatian is spoken since medieval times. Given the fact that they are located primarily in the northwest, they are peripherally located and have features of marginality. That means that while the Slavonian dialect is undoubtedly Shtokavian, it does connect in some ways quite closely with both the Chakavian and the Kajkavian dialects.

One might assume, given Slavonia's geographical position, that the Slavonian dialect would have far, far more in common with Kajkavian. Such an assumption would be more than logical, but as I'll explain a little further down, endless migration and settlers from elsewhere made sure that Shtokavian was far more prominent.

Croatian history has been turbulent for an incredibly long time, and with the invasions of the Ottomans and various changes of power and even recognised states, one can imagine the sheer amount of migration that has taken place in and around these lands as the centuries have passed by. This naturally had an enormous effect on the languages spoken, where they're spoken, and how they're spoken. It is precisely because of strong waves of migration over time that the linguistic connections between the Slavonian dialect and the Kajkavian dialect were largely severed, but the results of these old connections are still evident in the details if one looks closely (and of course, if they know what they're looking at).

The demographic crisis in Slavonia isn't something that came about recently or even during more modern historical periods. Back during the rule of the Ottoman Empire, Slavonia lost a very significant part of its local population, attracting the populations of what were then much poorer neighbouring regions. Settlers from Herzegovina were abundant in Slavonia, and they naturally heavily influenced the physiognomy of the native population's speech over time.

As I touched on above when I mentioned Slavonia's position on the map and the proximity of Kajkavian speaking areas to it, one would assume that Kajkavian would have more of a ''say'' in the Slavonian dialect, and historically, you'd be right for assuming so. In a historical sense, the Slavonian dialect was once closely connected with Kajkavian, but migrations and new settlers from elsewhere changed that, and as a result of those very migrations, this connection decreased and decreased, and in some cases it was even broken entirely. The Podravina subdialect is more or less the only subdialect which has done well to retain its Kajkavian speech connection.

For more on the Croatian language, dialects and subdialects, as well as learning to swear in Croatian, make sure to check out our dedicated lifestyle section.

Exploring The Croatian Language - The Gorski-Kotar Dialect

March the 6th, 2023 - The Gorski-Kotar dialect is a dialect of Kajkavian, and is spoken in the narrower area of the boundaries of Gorski Kotar, all the way to the upper reaches of the Kupa river.

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian.

Where is the Gorski-Kotar dialect spoken?

While its name might lead one to the apparently blindingly obvious conclusion, as touched on above, the Gorski-Kotar dialect is actually spoken in the very distinct area of the upper part of where the Kupa River flows and then further east, reaching all the way to the outskirts of what is classed as the region of Gorski Kotar. It's a form of Kajkavian, and so the way the words are formed, accentuations and most of its general features are clearly Kajkavian. That said, it also boasts features of both the Chakavian and modern Slovenian languages.

Kajkavian is very widely spoken and is one of the main dialects that makes up modern standard Croatian. It contains many dialects of its own, from Eastern Kajkavian to Northwestern and Southwestern Kajkavian. The Gorski-Kotar dialect is just another in a list.

A little history involving former Croatian territory...

Jumping across the Croatian-Slovenian border for a minute or two, we can how linguistics in this area and an often turbulent history has intertwined over time, as speech with many features of the Gorski-Kotar dialect has stretched to the border areas on the (modern-day) Slovenian side of the Kupa river (more specifically areas of Bela Krajina and Pokuplje), which was where Croatian feudal lords had many of their fancy estates once upon a time.

In brief, the Gorski-Kotar dialect is a type of transitional speech that originated in an originally Chakavian area and then along the Kajkavian-Chakavian border a little south of the Kupa river which flows through both Croatia and neighbouring Slovenia

It's worth noting that Bela Krajina, which is now Slovenian territory, was then part of Croatia, and much later it also became part of the wider Zagreb diocese. The entire wider area was quite dramatically changed by populations of migrants to the north, fleeing the arrival of the marauding Ottomans across the region, and later the return of that native population from the area of lower Kranjska (Dolenjska), now Slovenia.

For more on the Croatian language, including histories on the various dialects and subdialects, as well as learning how to swear in Croatian, make sure to check out our dedicated lifestyle section.

Exploring Croatian Language - The Southwestern Kajkavian Dialect

February the 27th, 2023 - The Southwestern Kajkavian dialect, sometimes referred to as the Turopolje-Posavina dialect, is one of the main dialects which makes up Kajkavian.

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian.

With so much variation of what standard Croatian is, you won't be surprised to learn that there are dialects in dialects, and then subdialects thrown in the mix as well. While Kajkavian is a dialect, one of the main ones making up standard Croatian, it has numerous dialects of its own, including the Northwestern dialect, and the Eastern one. In this article, I'll talk about the Southwestern Kajkavian dialect, which was, like many others, once much more widely spoken than it is today.

Where can the Southwestern Kajkavian dialect be heard?

Delving back into the not so distant past, the Southwestern Kajkavian dialect could be heard being spoken across the old area of the wider Zagreb County, with the exception of its very outskirts where Prigorski was primarily spoken. It has several subdialects of its own which certain linguists consider to instead be dialects in their own right.

Fast-forward to the modern day, it is still spoken in the area of Posavina from Zagreb and to the area in which Jekavian (the southern dialect) is primarily spoken in the areas of western Slavonia and along the modern-day Croatian border with neighbouring Bosnia and Herzegovina. Heading further up north, the spoken Southwestern Kajkavian dialect extends to the area of Moslavina, where it borders the Eastern Kajkavian dialect.

Outside of Croatian borders

While of course not the same, the dialects spoken in Austria's Gradisce (Burgenland) and Romania's Karasevo are believed to originate from Southwestern Kajkavian. Karasevo in particular is known for its Croatian residents (the Krashovani).

For more on the Croatian language, including history, dialects, subdialects and even extinct languages, make sure to follow our dedicated lifestyle section. An article on language (even on how to swear in Croatian) is published every Monday.

15 Croatian Language Fails: Smallpox, Hand Jobs and a Burek Called Desire

February 22, 2023 - Lost in translation, the video edition - 15 Croatian Language Fails: Smallpox, Hand Jobs and a Burek Called Desire.

I have very rarely cried with laughter when reading an article online, but TCN editor got me crying three time in the same month with her fabulous Lost in Translation series about Croatian language fails a few years ago.

You can find links to the original articles by Lauren below, but we thought it might make a fun video to compile the best of the best.

15 Croatian Language Fails: Smallpox, Hand Jobs and a Burek Called Desire goes out live tonight at 19:53. Click on the video to get the notification.

Hope you enjoy.

Smallpox, Diarrhoea and Free Hand Jobs: Lost in Translation in Croatia - https://www.total-croatia-news.com/lifestyle/21467-lost-in-translation-the-croatia-edition

Leprosy, Bitches and a Burek named Desire: Lost in Translation in Croatia - https://www.total-croatia-news.com/lifestyle/21743-leprosy-bitches-and-a-burek-named-desire-lost-in-translation-in-croatia

Shakespeare, the Pope and the Way to the ''See'': Lost in Translation in Croatia - https://www.total-croatia-news.com/lifestyle/24083-shakespeare-the-pope-and-the-way-to-the-see-lost-in-translation-in-croatia

Adverbs, Cocks and Dalmatian Furniture: Lost in Translation in Croatia - https://www.total-croatia-news.com/lifestyle/24100-adverbs-cocks-and-dalmatian-furniture-lost-in-translation-in-croatia

Winos, Doggy Style and Strange Furious Drinks: Lost in Translation in Croatia - https://www.total-croatia-news.com/lifestyle/24144-winos-doggy-style-and-strange-furious-drinks-lost-in-translation-in-croatia

Lubricator, Prefects, and Middle-Earth Moving Cake: Lost in Translation in Croatia - https://www.total-croatia-news.com/lifestyle/30209-lubricator-prefects-and-middle-earth-moving-cake-lost-in-translation-in-croatia

Paper Sauce, Bears, and Fertilisers of Rice: Lost in Translation in Croatia - https://www.total-croatia-news.com/lifestyle/30255-paper-sauce-bears-and-fertilisers-of-rice-lost-in-translation-in-croatia

Prize Lists, Cold Deposits and Viagra: Lost in Translation in Croatia - https://www.total-croatia-news.com/lifestyle/30684-prize-lists-cold-deposits-and-viagra-lost-in-translation-in-croatia

Lost in Translation in Croatia: Bears, Acid, and Worm Appetisers - https://www.total-croatia-news.com/lifestyle/37599-croatia

****

You can subscribe to the Paul Bradbury Croatia Expert YouTube channel here.

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning - Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners is now available on Amazon in paperback and on Kindle.

Exploring the Croatian Language - The Buzet Dialect

February the 20th, 2023 - If you're into linguistics, you've more than likely heard of Chakavian, which is one of the main dialects of standard Croatian as we know it today, and which was officially declared a language back in 2020. What about a dialect of Chakavian itself, such as the Buzet dialect, however?

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian.

The Buzet dialect is just one of a multitude of dialects and subdialects spoken in and around the region of the Istrian peninsula, which was dominated by Italian for a very long time owing to the formerly powerful Venice. Contrary to popular belief (and what the bilinguial signs across Istria might have you believe), there is far more than just Italian spoken alongside standard Croatian in this part of the country. Istro-Venetian, Istriot, Istrian-Albanian (now extinct), Istro-Romanian... the list goes on. All of these dialects, which some linguists consider to be languages in their own right, showcase the sheer amount of culture and foreign influence that has come and gone in Istria throughout the many centuries gone by, and as you can see - it stretches far beyond the realms of Italian and the former Venetian Empire.

A brief history of the Buzet dialect

The Buzet dialect, a dialect of the much more widely spread Chakavian, is particularly interesting as it is believed to represent the transition of Chakavian towards the dialects spoken nearby, just across the border in neighbouring Slovenia. It is precisely this linguistic relationship which provides the Buzet dialect with (in many cases) very obvious Chakavian-Kajkavian dialectological features.

Owing to the presence of these transitional features of Kajkavian (and not only Chakavian), which actually represent a transitional line between the Chakavian and several Slovenian dialects, numerous linguists once thought that this separate part of the Kajkavian dialect had found itself in the northern part of Istria and in Buzet from the wider region of Gorski kotar. It was even considered to be a marginal Slovenian dialect in the past. This is now deemed to have been a mistake made by the Slovenian linguist Fran Ramovs.

Who was Fran Ramovs?

Born in the Slovenian capital city of Ljubljana, this prominent linguist studied and explored the various dialects of the Slovenian language in Vienna.

Where is the Buzet dialect spoken?

Well, the name likely gives it away. It is spoken in and around the area of Buzet, but it spreads considerably across the northern part of Istria as well.

The background of this dialect now considered to undoubtedly be Chakavian, there are still some features that make it stand out it from the rest of the Chakavian dialects spoken in the modern day, and one of those features are its consonants and how they've developed. Delving a little deeper, even the Buzet dialect, which is a dialect of Chakavian (which was also once considered a dialect!) can be divided into two separate subdialects; the southeastern subdialect, which is an apparent transition towards North Chakavian, and then the rest of it which is more widely spoken and which doesn't show as many North Chakavian transition points.

In the wider division of Chakavian into its northwestern and southeastern dialects, the Buzet dialect is considered to be northwestern.

For more on the Croatian language, from its dialects, subdialects, history and even learning to swear, make sure to follow our dedicated lifestyle section. An article on language is published every Monday.

Exploring The Croatian Language - The Eastern Kajkavian Dialect

February the 13th, 2023 - If you're interested in linguistics at all, you'll more than likely have heard of the Kajkavian dialect. As one of the main ''pillars'' of modern standard Croatian, it is spoken by a large amount of people. You might have even heard of the Northwestern Kajkavian dialect. What about the Eastern Kajkavian dialect, however?

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian.

A brief history of the Eastern Kajkavian dialect

The Eastern Kajkavian dialect, one of the main dialects which make up Kajkavian as a whole, was once considerably more widely spoken than it is now. Sometimes referred to as the Krizevci-Podravina dialect (Krizevacko-Podravski), it is characterised primarily by several ''far-reaching'' alterations when it comes to accentuation, and the placement of the accent is more or less entirely limited to the last two syllables of any given word.

In the past, the spread of spoken Eastern Kajkavian spanned different areas of the ''old'' Krizevci County, and continued on into the Scakavian-Kajkavian regions of the wider Danube Region.

Where is it spoken now?

Fast forward to the modern day, and the Eastern Kajkavian dialect is spoken in the general area of Moslavina and Podravina from Koprivnica all the way to the parts of western Slavonia which are more or less entirely diominated by Neo-Stokavian-Jekavian (also known as the southern dialect) speakers. In the eastern part of that same region, it intertwines with the Podravina subdialect of Slavonian Skakavica, with which it was once more closely linguistically connected.

Like with many lesser spoken languages, dialects and subdialects, there is always at least a little bit of controversy, and the Eastern Kajkavian dialect, like an array of others, can be divided into several smaller subdialects which some linguists consider to be independent dialects of their own.

Mijo Loncaric, a very well respected Croatian linguist and an expert in not only dialects but in Kajkavian itself, is one of those language experts who consider the so-called ''subdialects'' of the Eastern Kajkavian dialect to be dialects in their own right.

For more on the Croatian language, including information on dialects, subdialects, history and even learning how to swear in Croatian, make sure to keep up with our dedicated lifestyle section. An article on Croatian language is published every Monday.

Croatian Language - The Difference Between Dalmatic and Dalmatian

February the 6th, 2023 - You might have heard of Dalmatian (and I'm not talking about the ones Cruella tried to make coats out of), but have you ever heard of Dalmatic? In this edition of our series on all things to do with the Croatian language, dialects and subdialects, we'll explore why they're not one and the same.

A brief history

Not to be confused with Dalmatian, the Dalmatic language is now extinct. It belonged to the wider group of Italo-Dalmatian family of languages and was once spoken along both the Croatian and Montenegrin coastlines. What makes Dalmatic so interesting is that the date of its disappearance from use is very precisely known - June the 10th, 1898, when the last speaker of a form of this language (known as the Vegliot dialect), Tuone Udain, died. You can read more about Tuone, who was born on Krk and was unfortunately killed during a road mine explosion, by clicking here.

Dalmatinski (Dalmatian) and Dalmatski (Dalmatic), what's the difference?

Here's where it gets linguistically tricky thanks to our good old (and awkward) friend - terminology. In the Croatian language, Dalmatic (Dalmatski) is the common name for this language, and it should never be confused with Dalmatian (Dalmatinski). One is a Slavic language and one is a Romance language.

The Dalmatian language, i.e. a dialect or a set of dialects, refers to various spoken versions of the Croatian language, which belongs to the wider group of Slavic languages. The Dalmatic language does not belong to the Slavic language family and is actually a Romance language which originated from Latin and was spoken all along the eastern Adriatic coast, this means that Dalmatian and Dalmatic are not at all closely related outside of the basic fact that both Slavic and Romance languages share a common ancestor as they belong to the far wider group of Indo-European languages.

Where did Dalmatic come from?

The Dalmatic language first came to be way back during Middle Ages as a direct continuation of spoken Latin in the then Roman Dalmatia, sharing the same spontaneous origins of most other Romance tongues. Latin language was the most important and most heavily used language at the time, and Dalmatic wasn't used for any official purposes, with the occasional exception of Dubrovnik (Ragusa) where it has been discovered in some old notarial documents. The oldest Dalmatic texts we know of date from way back in the thirteenth century, and were written in the Ragusan (Dubrovnik) subdialect.

How did it become extinct?

The use of Croatian (a Slavic language) began to gain a lot of ground and spread across a wider and wider geographical area, and Italian and Venetian also took hold across vast parts of modern Croatia owing to the power of the Venetians at the time. Unfortunately, this saw spoken Dalmatic become extinct, with the Zadar version of spoken Dalmatic likely dying out first, and Ragusan ceasing to exist during the sixteenth century.

Native Dalmatic speakers once resided on the Croatian islands of Rab, Cres and Krk, in numerous coastal Croatian cities, including Trogir, Split, Dubrovnik and Zadar, and further south across the border in neighbouring Montenegro (Kotor). The most well known regional Dalmatic dialects were Ragusan (Dubrovnik), Vegliot (Krk), and the local dialect spoken in Zadar (Jadera).

For more on the Croatian language, including learning it, looking into the history of the dialects, subdialects and extinct languages, and even learning to swear, make sure to check out our lifestyle section. A new article on the Croatian language is published every Monday.

Chakavian Officially Declared a Language in 2020, Croatia Pays No Attention

January the 30th, 2023 - Back in 2020, the Chakavian ''dialect'' was officially declared a language in its very own right. The Croatian media paid absolutely no attention to it whatsoever, despite Chakavian being one of the three ''dialects'' from which modern standard Croatian is derived.

As Rijeka Danas/Marin Tudor writes, back during the pandemic-dominated year of 2020, without much fanfare and completely unnoticed by local media, Chakavian became a language which was officially recognised by the main international academic organisation that deals with the classification of all languages spoken by mankind. Chakavian thus received its own special ISO language ID code: ckm

This significant (at least linguistically) historical event paves the way for Chakavian speakers to receive much greater local and national recognition, which has been totally lacking until now because Chakavian was considered to merely be yet another dialect.

American professor of linguistics from the prestigious University of California, Kirk Miller, known in the academic world as a successful field linguist responsible for the research and popularisation of the lesser-known languages spoken by mankind, thought about the need to perpetuate Chakavian as one of the languages of our world.

Seeing that nobody had remembered to classify and identify Chakavian as an official language, Miller himself decided to send a painstakingly thought out and written request on September the 2nd, 2019, for the recognition and documentation of the Chakavian language to an organisation called SIL International.

The Summer Institute of Linguistics International is the full name of an international non-profit organisation based in Dallas, Texas, whose main purpose is to study, develop and document all languages used throughout the world, with the aim of expanding linguistic knowledge, promoting literacy in all languages, and ensuring the language development of linguistic minorities.

Once a year, SIL International publishes the prestigious academic magazine Ethnologue. It is a reference publication available both in print and online that provides statistics and other information about the world's living languages. What is actually perhaps an even more important responsibility of SIL International is to issue ISO type 639-3 codes for comprehensive coverage on behalf of the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO, based in Geneva - of which Croatia is a member).

It is interesting to note that Professor Miller based a part of his request on the previous request of the main association of speakers of the Kajkavian language, which already managed to win the recognition of Kajkavian as an independent language back in 2014. SIL International then recognised Kajkavian as an independent language, but only in the literary form that was used in the period from the 16th to the 19th century and in some works from the 20th century.

Miller's entire argument was already confirmed as valid by SIL International back in 2020. Owing to his efforts, the Chakavian language was given the highest possible linguistic recognition that exists: it was recognised as a living (independent) language of its own, and not merely a dialect.

Who actually invented the word ''narjecje'' - the term the Croatian language mixes up with ''dialect''?

Chakavian and Kajkavian have long been considered languages in the international world of linguistic science, and not a mere branch of the Croatian standard language, that is, the Shtokavian Croatian language as we know it. Of course, both languages are actually much older languages than the standardised version of Shtokavian (in the first few centuries, all Croatian dictionaries were actually written only in Chakavian), which continued to exist and develop even after the creation of that standard, so, they in fact cannot be dialects of that standard at all. Chakavian might even be considered an international language of sorts, because it is spoken in Croatia and in four other member states of the European Union (in Slovenia, Austria, Hungary and Slovakia).

Despite this, former Yugoslavian (and later a significant number of Croatian linguists) placed both Chakavian and Kajkavian in the category of "dialects" (narjecje) for decades.

The very term "narjecja" has always been a disputed concept when it comes to linguistics outside the vague borders of the Balkans. It's enough to know that there is no direct translation for this word in any other language of the world, nor is there one for the concept that we encompass within that word. In international linguistics, only the terms "language", "dialect" and "sub-dialect" are known. That is why Croatian and ex Yugoslavian linguists were forced to invent a rough English translation for the word themselves - "supradialect" (i.e. super-dialect) - in the desire to explain to the whole world the local concept of something that has all the linguistic, social and historical characteristics of a language, but we for some reason or another have the need to consider less than a language.

As is often the case, this approach is the product of the fact that in Croatia, political circumstances heavily directed science, and it wasn't that science gave the main direction to politics: the Croatian people fought frantically for their place under the sun for almost a century and a half. Being recognised by the world as an independent national community required enormous effort, dogged determination and deep desire of more than six generations of Croats. That meant that entire generations of Chakavian and Kajkavian intellectuals and scientists preferred to neglect their mother tongue and native culture in favour of the greater good of the entire Croatian nation, of which they strongly felt a part throughout history. It was a logical and noble move at the time, but it has left its scars.

Language – the soul and heart of any culture

"If a culture were a house, then language would be the key to the front door, and to all the rooms in it,'' says Khaled Hosseini, an American writer and doctor born in Afghanistan, who was also New York Times' bestseller three times.

Language is indeed the very essence of culture, because its soul begins and ends with language. It shapes the way people think, dream, communicate with each other, build relationships and create a sense of community. It's the main guardian of a value system, because it directly transmits a set of symbols, meanings and norms.

It is that first form of communication with the universe, those first children's words that initiate verbal contact between people. Knowing one's linguistic roots so well automatically enables one to more easily identify with the community around them and to keep the welfare of that community close to their hearts in the deepest sense.

Language is a technology that enhances and expands the capacities of categorisation that we share with those around us and those who came before us, and therefore plays a key role in the transmission of human culture to those who will come after us.

All of this of course also applies to that part of Croatia where Chakavian is the autochthonous language. Croatian culture will disappear when and if the languages on which it is based are lost to the hands of time. This isn't such an incredible possibility: if we continue with today's trends, it is quite likely that in two generations, Chakavian will more or less have the status of an extinct language. When it disappears, native Croatian culture will also disappear with it.

Unfortunately, the statesmen and strategists of Croatia's national branding failed to use the independence of our country, nor the next three decades of freedom, to valorise the linguistic and cultural specificities of its native people. If the Republic of Croatia and its representatives believe that culture is at least somewhat important, then they will have to activate themselves and work much harder to promote the Chakavian (and Kajkavian) languages.

Chakavian's future

This international recognition for the Chakavian speaking world is not only significant, but a truly epochal event. At the global level, the Chakavian language will be studied more seriously and more study and learning of the Chakavian language will be promoted at Slavic departments of universities outside of Croatian borders. A small boom in academic and non-academic literature on the Chakavian language is also to be expected over the next few years.

But above all, this brand new status will really open the door wide for Chakavian speakers to request official recognition of their language where it most needs to be recognised, that is, in the countries where Chakavians have lived for almost 1,500 years and maybe for even longer. It would indeed be a very sad and perversely ironic historical turning point if, after surviving all kinds of enemy invasions, legal prohibitions and changes in language fashions for at least twelve long and arduous centuries, the Chakavian language dies out precisely in the era of the first truly independent and free state of the Croatian people.

The international recognition of the Chakavian language and Croatia's next steps will thus surely become an important cultural factor on the European path of this proud little country and Croatian civilisation itself, because in Europe, local and minority languages have been lovingly nurtured for decades, and unique languages have some very efficiently (and profitably) regional and national brands built on them, and through these, the true respect of the people towards their local communities is promoted.

All municipalities and counties in which Chakavian is the original autochthonous language are now given the opportunity to recognise Chakavian at the very highest level, as a parity language alongside the standard one, and it is now the turn of Croatia to launch some proper initiatives and political guidelines to first preserve the language, and then to help the Chakavians to standardise it all to some extent and effectively promote it at both the local and global level.

Of course, this requires a lot of work and the orchestrated multi-year work of all participants in the Chakavian speaking world, but the goal is a worthy one and one which is definitely achievable (especially with the help of all the instruments and means offered by the European Community for these purposes). If it is possible to revive languages that have completely died out in Cornwall and the Isle of Man under the constant pressure of the most heavily spoken language in the world (English), or to revive the unwritten Maori language in New Zealand, then reversing the negative trend of a language that is still fluently and daily used by hundreds of thousands of people in a modern European country can't be that hard at all. It only requires good will, diligence and, of course, love. Things that were never missing among Chakavian speakers.

For more on the Croatian language, make sure to check out our dedicated lifestyle section.