The Vegliot Dialect - The Krk Romance Language Extinct Since 1898

January the 23rd, 2023 - The Vegliot dialect, which is also often referred to as Vegliotic, is a now extinct Romance language once spoken on the island of Krk. The last speaker of the Vegliot dialect was Antonio Udina (Tuone Udaina), who passed away in June 1898. Little is known about the dialect named after the Italian name for Krk (Veglia).

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian.

A brief history of the Vegliot dialect

Of the now extinct languages once spoken on modern Croatian territory, we've looked into Istrian-Albanian, which became extinct in the nineteenth century after being introduced to parts of Istria by ethnic Albanians settled there by Venice who spoke in the Gheg (or Geg) variety of modern Albanian. Now we'll jump back into our linguistic time machine and head back into the island of Krk's past, during which the Vegliot dialect was spoken all the way until June 1898, when the last person to speak it died.

As mentioned above, the Vegliot dialect is named after the Italian name for Krk - Veglia, and its closest ''relative'' is believed to be Istro-Romanian, another Romance language once spoken more widely spoken across the Istrian peninsula, more precisely in the nothwestern parts near the Cicarija mountain range. There are two groups of speakers despite the fact that the language spoken by both is more or less absolutely identical, the Vlahi and the Cici, the former coming from the south side of the Ucka mountain, and the latter coming from the north side.

This language has been described as the smallest ethnolinguistic group in all of Europe, and without a lot more effort being put into preservation, the next few decades to come will almost certainly result in the complete extinction of the Istro-Romanians and their language.

A Western Italian dialect of Dalmatic, the Vegliot dialect was once spoken by a group of Morlachs (pastoralists) who were engaged in herding. As each of these individuals passed away, the last remaining was speaker was the aforementioned Antonio Udina, who was often affectionately called Burbur.

Antonio Udina (Tuone Udaina)

Udina was born in 1823 on the island of Krk, and died on June the 10th, 1898, losing his life in a road mine explosion and taking the Vegliot dialect with him into the beyond. Nicknamed Burbur, Udina is deemed the last person to fluently speak in the Vegliot dialect, but he was in actual fact not a native speaker of this language. He had learned the dialect (or language, for argument's sake) from his parents who both hailed from the island of Krk and spoke it as their native tongue.

Well known Italian linguist Matteo Bartoli wrote a paper on Dalmatian/Dalmatic language(s) way back in 1897, in what was to be the final full year of Udina's life. At that time, Udina had not spoken in that language for around twenty years, and he had also suffered dental issues so severe they had affected the movements of his mouth and as such he speech, and on top of that - he was also deaf.

Despite being deemed the last speaker of the Vegliot dialect, he is not considered a reliable source in regard to this language owing to his health issues. That said, after Udina was killed in a road mine explosion, the Vegliot dialect also died and is unlikely to ever be heard again.

For more on the Croatian language and the many dialects and subdialects spoken across this small but diverse country, make sure to check out our lifestyle section. An edition on language is published every Monday.

Exploring The Croatian Language - The Shtokavian Dialect

January the 16th, 2023 - We've looked into many a dialect, but what about what's known as a ''prestige dialect''? of the modern (standard) Croatian language? A look deeper into the Shtokavian dialect, part of the wider family of South Slavic dialects.

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously.

That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian. Shtokavian is far less obscure than the majority of the above, with the exception of Kajkavian and Chakavian, and forms the basis of the Croatian language standard as we know it today.

If you're not a linguist and you hear the words Shtokavian, Kajkavian or Chakavian, you're probably thinking ''what?!''. Did you know that the question of ''what'' is so valid in this context that it makes up the beginning of each of these names? In the parts of the country where the Western Shtokavian dialect is dominant, the Croatian word for ''what'' is ''shto'', and for the areas of the country where Kajkavian is used, the word for what changes to ''kaj'', and - you guessed it - for Chakavian, people typically say ''cha''.

Where is the Shtokavian dialect used?

In the modern day, Shtokavian is used in much of Croatia, as well as in Montenegro, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and even in parts of Austria (more precisely in Burgenland).

A brief history of the Shtokavian dialect

For the sake of this article not turning into a book, I'll be focusing on the use of the Shtokavian dialect solely in the Croatian sense, and we first see it appear way back in the 12th century, then splitting off into two zones; Eastern and Western - one encompassed Serbia, the more eastern parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina and further south in Montenegro, while the other was dominant in Slavonia and in most of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

We can read early texts written in the Shtokavian dialect which are dated as far back as the 1100s, one of the most important of them all being the regulation of commerce between Dubrovnik and Bosnia, called the Ban Kulin Charter. Other legal documentation also boasts the dialect from across Dalmatia during the pre-Ottoman era, and Dubrovnik stands out quite a lot in this regard. Another important text written in the Shtokavian dialect is the Vatican Croatian Prayer Book which was published before the year 1400 in Dubrovnik.

Are there different dialects within the wider Shtokavian dialect?

In short - yes. There are a great many dialects (or subdialects) of the Shtokavian dialect which are or were spoken in different areas of not only Croatia but within the wider region. As I said before, for the sake of this article not becoming a book, I'll focus only on Shtokavian spoken in Croatia, and as such draw your attention to Slavonian (old Shtokavian), Bosnian-Dalmatian (neo Shtokavian), Eastern Herzegovian (neo Shtokavian) and the Dubrovnik subdialect (neo Shtokavian).

Slavonian

Meet Podravian/Podravski and Posavian/Posavski (just when you thought this couldn't possibly get any more needlessly complicated). This form of speech is spoken primarily by Croats from Baranja, Slavonia and areas of the wider Pannonian plain. The aforementioned subdialects (Posavian and Podravian) are the northern and southern variants of the dialect, and there are ethnic Croats who speak it outside of Croatia's modern borders in parts of northern Bosnia, as well. The two subdialects boast two accents, Ikavian and Ekavian.

Bosnian-Dalmatian

This dialect is sometimes referred to as Younger Ikavian and most people who speak it are ethnic Croats from a wide range of modern Croatia - spanning from Dalmatia all the way to Lika and Kvarner. Outside of Croatian borders, you'll also find people who speak it in Subotica (Serbia) and in Herzegovina, and to a much lesser extent in areas around Central Bosnia. Unlike with Slavonian, the only accent heard in the Bosnian-Dalmatian pronunciation of the wider Shtokavian dialect is Ikavian.

Eastern Herzegovian

This is the most widespread subdialect of the Shtokavian dialect of all, encompassing vast areas of Croatia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. Of all of the subdialects of the Shtokavian dialect, Eastern Herzegovian (or Eastern Herzegovinian) has the largest number of speakers.

The Dubrovnik dialect (Ragusan)

You can read more about the Dubrovnik dialect (or subdialect) by clicking here.

Standard Croatian is based on the neo Shtokavian dialect, but despite that, it took over four centuries for this dialect to gain enough ground and eventually prevail as the basis for modern Croatian, with other dialects (including Kajkavian and Chakavian) falling short primarily owing to not only historical reasons but because of usually turbulent political issues.

For more on exploring the Croatian language, as well as the numerous dialects and subdialects spoken in different areas across the country, and even a look into endangered and extinct languages, make sure to check out our dedicated lifestyle section.

Exploring the Languages of Croatia: Bosnian/Bosniak/Bošnjački

January the 9th, 2023 - The Bosnian language, or Bošnjački jezik, if you want to say it in the local way, is a tongue belonging to the western subgroup of the wider south Slavic language family. It's worth mentioning straight away that it is rather ambiguous for many people here in Croatia, and has attracted many a dispute from linguists and other experts.

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian.

Standard Croatian is far from the only language or dialect spoken in this small country, and some have more rights than others based on their level of dispute and controversy. While some, such as Istrian-Albanian, are now extinct as a result of a lack of preservation and/or a rapidly dwindling number of speakers, others are widely spoken but attract significant debate. The so-called Bosnian language is one of them.

Bosnian, Bosniak, Bošnjački - the basics

Let's start with the basics and say that in Croatia, the Bosnian language is usually called the Bosniak language. As I touched on above, this language attracts debate very often, and as such, you'll likely face corrections no matter what you call it. The issue with this has little to do with the formation of spelling of the word, but instead with historical ties to the country (Bosnia), and the terminology used when referring to it.

Bosnian (as it is called in Bosnian), or Bosniak (as it is called in Croatian), as you might have guessed, is one of the three official languages spoken in neighbouring Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other two being Croatian and Serbian. The use of Bosnian, despite being a language which has no difficulty in attracting linguistic arguments, especially here in Croatia, is widespread, with over two million individuals spanning the territories of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, Montenegro and Serbia speaking it.

Members of the diaspora, along with their descendents, across Western Europe, North America and even much closer to home in Turkey, also speak Bosnian, although their precise numbers have never been confidently determined.

Bosnian is very similar to Croatian and Serbian, but developed down its own path as a result of Ottoman Turkish influence, which reigned strong in Bosnia and Herzegovina for a very long time. There are also Arabic and modern Turkish influences thrown in there, as well. Despite having an array of influences thrown into the mix, Bosnian is primarily based on four main subgroups of the Shtokavian dialects, with Shtokavian also being one of the pillars of standard Croatian, alongside Cakavian and Kajkavian.

A brief history and a (past) Croatian connection

On a small scale only, Bosnian leans on the Ijekavian pronunciation of modern Serbian but there are an abundant use of Turkish words to be found, and anyone with an interest in language and knowledge of Croatian will be able to instantly point them out. The language evolved and changed throughout the centuries, with the first Bosnian-Turkish glossary being published in 1631. Fast forward a few years to the post-Ottoman occupation period, more specifically to the nineteenth century, the much more extensive cultural activity of Bosniaks appeared in a language that was constantly referred to as something different: Serbo-Croatian, Croatian, Serbian, and then Bosnian. The Austro-Hungarian monarchy's long rule also led to the predominance of the Latin script across its former territories (which included modern Croatia in a very large part), giving birth to a (by then) much more visible Bosniak language, which was much, much more like Croatian than Serbian back during those times.

Where can the largest number of Bosnian speakers be found in the modern day?

In this day and age, the largest number of Bosnian speakers live in Bosnia and Herzegovina - more precisely in the cities of Sarajevo, Bihac, Tuzla and Zenica, with some other locations also having a significant number of people who claim it as their mother tongue. Just over 1.5 million people who claim their mother tongue to be Bosnian live in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Disputes about the name, and where Croatia stands when it comes to Bosnian

There are a considerable number of people (just under 10,000 of them) who live in the Republic of Croatia who consider their mother tongue to be Bosnian, and the name ''Bosniak'' as Croatia typically refers to it, has and continues to be the subject of argument and debate from not only those in the world of linguistics, but also from politicians. Bosnian politicians believe Croatia should refer to it as Bosnian, and not Bosniak, and there are several Croatian linguists who very staunchly agree with the sentiment. Most Croatian language experts believe that nothing other than ''Bosnian language'' will do, and that such a title is the only appropriate one. Some linguists and experts who make up that very same group believe that Bosnian and Bosniak are actually two different things entirely.

Just to add to the confusion, in Croatia's 2001 census, this language is referred to as ''bošnjački'', while in the one which was carried out in 2011, the term ''bosanski'' is used, only furthering the ''Bosniak or Bosnian'' debate. Croatian state institutions, it seems, can't seem to make their mind up on this issue either.

For more on languages spoken in Croatia, as well as standard Croatian, dialects, subdialects and extinct languages, make sure to keep up with our dedicated lifestyle section.

Croatian Dialects World Cup Final: Hvar v Forests of Zagorje

January 7, 2023 - Croatian is a logical language, but it is the Croatian dialects that will kill you. How many of you can understand these dialect experts from Hvar and a forest in Zagorje?

As per my YouTube video a few weeks ago, I still maintain that Croatian is a logical language, but those je*eni dialects...

It is almost a decade since Professor Frank John Dubokovich, Guardian of the Hvar Dialects, stormed the Internet with his iconic Dalmatian Grunt. The Professor's ensuing niche series on Hvar dialects brought him a cult following of (mostly young, attractive, and female) dedicated followers. But the power of his message inspired others.

None more so that Grgo Petrov, who was so taken by the Professor's Dalmatian Grunt that he changed his university course and went on to dedicate himself to capturing Croatian dialects all over the country, as well as branching out with a whole range of dialect ideas and services. A little more about Grgo's dialect efforts (which are quite phenomenal) below, but here is the email he sent me to explain how the Professor had changed his life all those years ago.

Hey Paul!

We haven't met in person but you've had a huge influence on me and what I have been doing the last couple of years. It took me a long time to finally contact you haha.

I want to thank you for the Hvar Dialect Lessons you started posting on YouTube 5-6 years ago. I was in shock, just like the rest of my friends from Zagreb and the area. It was super entertaining but also educational. It made me think (and the rest of us) how our authentic local heritage was fading away. General unawareness of this local universe we have across Croatia.

What happened next is I started recording the "kajkavski lessons of Marija Bistrica" on YouTube with my local native speaker...in the end, I spent most of my University along with my Master's project all about preserving and promoting local dialects and values in Croatia.

I graduated as a visual communications designer, so I wrote and illustrated a tale in Kajkavski idiom, then posters and picture books for children... Following that, I started recording other people along the coast. Just last year spent two weeks on Dugi Otok island recording the locals' stories and their dialects. The project started connecting the locals across Croatia, raising awareness. Schools and parents are calling me for the presentations... it's just crazy.

And all of it kind of started when I saw the first "Hvar Dialect Lesson" you posted.

Cheers from Zagreb!

You can check out some of Grgo's dialect videos on his channel above - they are excellent.

We both thought the unthinkable - what about bringing the Professor to Zagreb to meet Grgo to do a special lesson, perhaps with one of Grgo's own dialect specialist. Someone like the lovely Martina, who Grgo literally discovered living in a forest (ok, in a village in a forest) in Zagorje.

Below is the result - and I am genuinely interested to hear how many Croats can understand the dialects spoken by Martina and the Professor.

You can see the rest of the Professor's iconic language series on the dedicated TCN YouTube playlist.

And now a little more about Grgo and his projects. If you would like to cooperate with him, you can reach him via his graphic design website.

Documented short interviews of Čakavski and Kajkavski dialects ... around the coast, islands, and Zagorje...mostly me asking questions in standard, them answering) ... I used to do research on the local dialect, talk to the linguists and local enthusiasts who connected me with interesting local speakers ... camera into my backpack and off we go!

Imbra Houstovnjak - kajkavski fantasy book and a master project at the School of Design, ZG ... the one I hope to publish this year as a bilingual edition...here's the original PDF available for reading. The goal was to give the Kaj-Croats a story in their mother tongue due to lack of the same, and connect the regions as, despite the differences, all of them can understand it. (Got positive feedback from a few schools in Zagorje that children read it with delight)

Imbra Houstovnjak across Croatia (same story in different dialect)

Imbra Houstovnjak Animated Audio book (first part) - a 5-minute video on YouTube with text, illustrations and narration by Martina Premor (the girl with Šumski dijalekt)

Priča o jednom Kaju (A story of Kaj) - illustrated educational picture book about the history and use of Kajkavski language in Northern Croatia. Teamwork with Croatian linguist Bojana Schubert from Ludbreg - approved by the Ministry of Education for the elementary schools. Published last year.

Croatian local Identity through original souvenirs - illustrated and designed popular merch with some of the local Zagreb, Kajkavski and Čakavski phrases with the help of local community... the webshop and the whole project is partially incognito as it's slowly developing in the background (working on packaging and finding local stores).

Moj prvi abecedar - a first Kajkavski illustrated alphabet for children with words from various dialects. Student project. Also in the line for funding hahaha (but Imbra Houstovnjak is a priority)

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning - Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Subscribe to the Paul Bradbury Croatia & Balkan Expert YouTube channel.

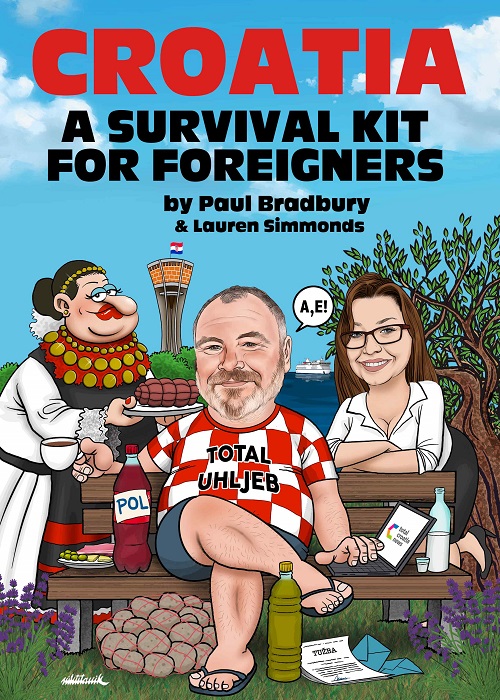

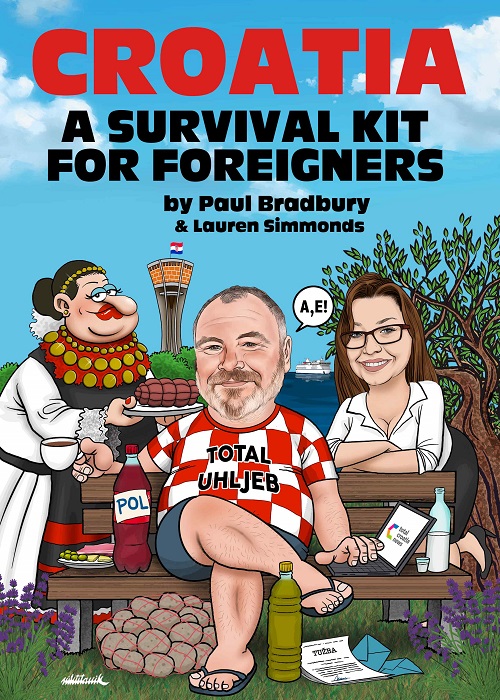

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners is now available on Amazon in paperback and on Kindle.

How to Croatia - Why You Absolutely Should Learn the Language

January the 4th, 2023 - In this edition of How to Croatia, we're going to be exploring the reasons why you should make the effort to learn the language, and that Croats having an excellent grasp of English should never a be a get out of jail free card.

I’ll be frank, learning Croatian is difficult unless you happen to have a Slavic language as your mother tongue. It has been listed as among the most difficult languages to pick up in the world on multiple occasions, and I’ll also be frank when I say many expats don’t bother trying to learn it. Do you absolutely need to be able to speak Croatian? Honestly, no. You’d get by. I’ve mentioned that the English language proficiency among Croats is very high. Should you learn to speak Croatian? Yes. And not only because it is the respectful thing to do when living in a country where Croatian is the official language, but because it will help you to adapt in a way that nothing else even comes close to.

Do you need to be fluent? Absolutely not. Croats are (unless the person is very ignorant to the world) aware that Croatian is difficult to learn. That said, as I mentioned before, any attempt at learning shows respect and will be greatly appreciated and even admired if you manage to get a bit more advanced with your skills.

It’s true when they say that the earlier you begin learning something, the more quickly and easily you’ll master it. Croatian kids converse very well in English, many of them take extra lessons outside of school, and a lot of them enjoy watching YouTube videos by American content creators and reading books written by British authors. I’ve met Croatian kids who actually don’t even like to speak in Croatian, choosing to instead speak in English among themselves, and lapping up the chance to practice to what is often fluency.

Given the fact that the English language is so desired and so widely spoken across the world, those who have English as a first language often speak only that. That of course isn’t always the case and claiming so would be a wild generalisation, but at age 13 with raging hormones and wondering whether or not Darren from the year above fancies you or not, it isn’t really the best time to soak up the ability to tell everyone what you did on holiday in French. This puts Brits especially at a disadvantage when it comes to properly learning foreign languages.

Croatian is made up of dialects, there are three main ones; Kajkavian, Shtokavian, and Chakavian, but the reality is that the way in which people speak can alter from town to town, let alone region to region. Someone from Brač (or as they call it - Broč) will struggle to understand someone from Zagorje, and vice versa. The way the time is told in some parts of the country is different from in another, and Dalmatian is a language with many unfortunately near-extinct words of its own. Did I mention that Dubrovnik language is also one of its own in many respects? Don’t get me started on different words being used on different islands which are a mere stone’s throw away from each other. There are words that the now dying generation use which, when they depart this life, will tragically go with them.

Some words in Croatian are so similar to each other in how they sound but mean wildly different things. Proljev is diarrhoea, and preljev is dressing. I cannot imagine a salad slathered in the former would be all that appealing. A friend once accidentally called her mother in law (svekrva) her ‘sve kurva’ (kurva means whore). Another person I know once said he had a headache (boli me glava), but ended up saying ‘glavić’ instead, which is part of the male sex organ. Given that ‘glava’ means head, you can probably guess which part ‘glavić’ is. My point is that this is a language which is intricate, and the little things make a big difference.

Croatian is a very colourful language. The ways people swear in this country and the creativity used is quite the art form in itself. The genitals of sheep, mice and Turkish people are dropped into conversations quite casually, and people refer to things being easy as a ‘cat’s cough’ or even as ‘p*ssy smoke’. I’ll be here all day if I carry on and explain all of their meanings, but rest assured, Croatian makes up for its infuriating difficulties with its imaginative creativity.

How do I begin learning Croatian?

Turn on your TV, your radio, and start reading news in Croatian language. You’d be surprised how much information having the radio or TV on in the background actually puts into your brain without you even actually listening. Children’s books are also extremely helpful if you’re starting from scratch.

Find a private Croatian teacher

Word of mouth and expat groups are your friend here. People are always looking for Croatian teachers and seeking recommendations for them. One question in an expat group will likely land you with several names of teachers with whom other users have had good experiences and progress with their language skills. Some teachers hold small classes, some do lessons over Skype, Zoom or another similar platform, and others will meet one on one.

Language exchanges

There are also language exchanges offered informally, where a Croat will teach you Croatian in exchange for you teaching them English, German, French, Spanish, or whatever language is in question. You both help each other learn the other’s skill, and it is a very equal affair.

Take a Croatian language course

Certain faculties and Croatian language schools, such as Croaticum, offer Croatian language and culture courses for foreigners. Did you know that you can also apply for residence based on studying here? There are different types of courses available and at reasonable prices. Some of them are even free! From semester-long courses on language and culture spanning 15 weeks and over 200 lessons to one month courses of 75 lessons spanning 4 weeks, there is something for everyone, depending on how much time they can or want to put into it. There are also others which offer Croatian language courses online, such as HR4EU, Easy Croatian, the Sputnik Croatian Language Academy, CLS and more.

If you have a Croatian partner, don’t rely entirely on them

Have them help you to learn, but don’t completely rely on them to the point that they’re your buffer stopping you from attempting to learn and improve. Many expats make this error, and their Croatian spouse actually ends up becoming an unwilling barrier to them picking up at least bits of the language in their perfectly noble attempts at helping. Stick some notes on household items with their names in Croatian. You’ll be calling a bed a krevet, a door a vrata, a wall a zid, a floor a pod, a window a prozor and a glass a čaša (or a žmul, if you want to take a step even further and learn a little old Dalmatian), in no time.

Age is a factor, so don’t run before you can walk

It isn’t a popular thing to say, but age does play a role when it comes to learning new skills, whatever they may be. Kids soak up new languages like sponges because their brains are developing, but with each passing year of our lives, that sponge gets a little bit drier. Croatian isn’t Spanish, it has very complex rules which are unlike what native English speakers have grown up using. You might find that you never truly master Croatian, and you might also feel as if you’re behind and not picking it up as quickly as you’d like to. This is normal, and it’s fine. Moving to or spending any significant amount of time in another country is a huge shift and for some people, throwing themselves into learning the language is last on the list in comparison to working out how to make ends meet or set up their lives. Nobody should be shamed for not having the same priorities as others might have. For some people, being a polyglot is just part of their nature, for others, it just isn’t. Patience is a virtue. Many expats will tell you that they understand much more Croatian than they’re able to speak, and if you can reach that level (which takes a while), you’re already much more than halfway there.

If you’re a member of the Croatian diaspora, the State Office for Croats Abroad has has scholarships available

If you’re a member of the Croatian diaspora, even if you don’t have Croatian citizenship and don’t have any intention of moving to or working in Croatia, you can still learn Croatian in various locations in Croatia and reconnect with your family’s roots and heritage.

I’m a translator. I translate from Croatian into English all day long, I could talk about my love and endless interest in linguistics all day (so I’ll stop now) and I can tell you that the two languages are very different in almost every aspect. It will not come easily, but genuine desire and consistent effort will surprise you with its results. Listen to Croatian, watch things in Croatian with English subtitles, have your spouse, friends and Croatian family members help you, don’t fear making mistakes and your confidence will grow. You will get there.

For more How to Croatia articles, which explore living in and moving to Croatia and span everything from getting health insurance to taking your dog on a ferry, make sure to check out our dedicated lifestyle section.

Exploring Croatian - The Oldest Known Slavic Alphabet - Glagolitic

January the 2nd, 2023 - Did you know that Croatia once used the oldest known Slavic alphabet? The Glagolitic script can still be seen in various parts of the country, and souvenirs sold across Croatia still bear it to this very day.

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian. What about Glagolitic?

A (very) brief history

To start off, it's worth noting that the origins of the Glagolitic alphabet are disputed to an extent. This can be said for most ancient languages and linguists are known to squabble over such things, but it is generally accepted that the script was created back during the ninth century by a monk from Thessalonica (today's Thessaloniki in Greece) called Saint Cyril, as well as to Saint Methodius, his brother. The very first observed mention of the word ''Croatia'' in the Glagolitic script dates back to around 1100 AD.

Another interesting fact about Glagolitic is that the precise number of letters in its original form is entirely unknown, but what we do know is that it is likely that Saint Cyril and his brother Methodius created the script in order to facilitate the introduction of the Christian faith, and we can assume with some level of certainty that the initial number of letters would have close to a Greek model. That said, there are elements of a variety of different languages within Glagolitic.

Over the many years, Glagolitic evolved with the population of its users and the tumultuous times they faced. It is certain that during the twelfth century, as Glagolitic in its original form (even with its non-Greek sounds) began to lose its grip, more and more Cyrillic influence could be found. As the centuries rolled on, more and more original Glagolitic letters were dropped, seeing the original number of letters drop to less than thirty in the Croatian recensions of what was called the Church Slavic language.

The use of the Glagolitic script in Croatia

The first Croatian Glagolitic book to be printed was Missale Romanum Glagolitice from 1483, and if you somehow managed to obtain a fully functioning time machine and took a quick trip back to the twelfth century and landed anywhere in Kvarner, Istria, Dalmatia, or even in Medjimurje, you'd have come across the Glagolitic script more or less everywhere. It's true that Glagolitic was mostly found in the coastal parts of the country, with notable areas being islands such as Krk (the Kvarner area) and the Dalmatian islands which sit just off the Zadar mainland, but traces of it stretched to Medjimurje (far inland), Lika, and even in parts of modern Slovenia.

For a very long time, it was accepted that the Glagolitic script was used solely in the aforementioned areas, but when 1992 rolled around and Croatia was engulfed in some extremely difficult times in its fight for independence and against Serbian aggression, some fascinating discoveries were made in old churches situated along the Orljava river in Eastern Croatia (Slavonia). This rather remarkable discovery blew previous theories about the locations in which this ancient script was used out of the water, and proved that it was also indeed used in Slavonia, something that was simply not even considered before.

While the twelfth century was in some ways a form of peak for the old Glagolitic script in Croatia, it did survive beyond that as the nation's main script, and for some time, but after a while, the development (or indeed decline) of this script was very poorly documented for a variety of reasons. Just before the marauding Ottomans began sniffing around the area, and before the Croatian-Ottoman wars truly began, the use of Glagolitic was at its very peak, and in today's measure, the amount of people using it back then would correspond to the amount of people in Croatia who use the Chakavian and Kajkavian dialects (two of the main dialects which make up modern standard Croatian) today.

The Ottoman wars and the decline of Croatian Glagolitic

The Ottomans and their invasions in the surrounding areas sounded the death knell for Croatian Glagolitic, and its stability in the region began to slip severely, with more damage being done to the use of this old script in areas more devastated and culturally altered by the Turkish forces. While the Ottomans certainly laid the heaviest of the groundwork to put the nails in Glagolitic's coffin, the real blow which set the wheels in motion for Glagolitic to meet its fate came much, much later, more precisely in the seventeen century, and by a bishop from Zagreb, no less.

The Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy, the west and the Italians

You've likely never heard of this conspiracy, as it's known in Croatia by this title, but to others it is simply called the Magnate conspiracy. In short, this conspiracy was an organised attempt to remove foreign influences (read Habsburg) from both Croatia and neighbouring Hungary during the seventeeth century. This left the Glagolitic script entirely without secular protection, and its use was severely limited, seeing it used only in the coastal region of modern Croatia. One century later, in the very late part of it, western influence saw to it that Glagolitic was to be no more. The culture and the script crumbled under secular pressures from the west, and it relied solely on printed material. By the time the twentieth century had rolled around and Fascist Italy did its bit in many part of modern Croatia, the areas in which the Glagolitic script had managed to cling on to existence suffered tremendously, and these areas were scaled back even more.

Glagolitic in modern day Croatia

Many ancient buildings, such as churches, still bear the Glagolitic script to this day, and of course, items bearing it can also be purchased across the country. The brand new Croatian euro coins with national motifs on them also proudly bear this ancient script, and it can be found on the 2 and 5 cent coins minted here. The 1992 discoveries in Eastern Croatian churches also shed light on the script, and those churches are in Lovcic and Brodski Drenovac. Some of the oldest stone monuments with the Glagolitic script engraved on them have been found in Istria and on the island of Krk, and in February each year, Croatian Glagolitic Script Day is marked in an attempt to preserve the rich and rather mysterious history of this script for generations to come.

For more on the modern Croatian language, dialects, subdialects, extinct languages, and learning Croatian, make sure to check out our dedicated lifestyle section.

Challenge Accepted: Let's Talk Croatian Language Horrors

December 21, 2022 - This is certainly the most comprehensive, as well as one of the most educational, replies to content I have posted online in the last 10 years - with thanks to Anamarija Pandža for this superbly (and humorously) explained introduction to the wonderful world of Croatian language horrors.

I have had a LOT of reaction to my blogs (and now vlogs) over the last 11 years since I started writing about Croatia, but I can't recall anything quite like this.

I recently started a YouTube channel called Paul Bradbury Croatia & Balkans Expert, a place where I am looking at life here over the last 20 years, and I have been stunned at the level of interest and engagement. The first 1000 subscribers (needed for monetisation) came after just 11 videos, and I have been enjoying interacting with my growing audience. It is the start of what could be quite a fun journey. If you want to subscribe to the channel, you can do so here.

One of the more popular videos has been this one above, 25 Most Common Mistakes Croats Make Speaking English. It was great to get so many messages from Croatians saying that they had learned something from the video (you are welcome), as well as the inevitable trolls demanding to know why I don't speak Croatian after 20 years here (hrvatski je svjetski jezik kojim govore samo najpametniji ljudi. Nisam toliko pametan, trudim se). On one of the comments, I for one would be keen to come across a similar article pointing out common mistakes foreigners make in Croatian.

And then, last night, I received this...

Hi Mr. Paul,

I don't even know how to start this email. So, let's just cut to the chase.

I recently came across your video on the 25 Most Common Mistakes Croats Make Speaking English. I liked it a lot. I found it intuitive and decided to accept your challenge in my somewhat perky way.

Why? I love writing. I love the Croatian language and orthography. I work as a freelance translator (and proofreader and content writer etc.), mostly for Booking.com, and I am experiencing a phase of decreased number of projects at the moment so I finally got time to write something that truly makes me happy. Also, I know my English is far from perfect, so I usually avoid writing in English. This is me leaving my comfort zone (big time).

I am sending you this as a sign of appreciation and acknowledgment of your video. But also to thank you for what you're doing for the promotion of our country and for fighting our mutual 'enemy':the National Tourist Board. This is actually what brought me to you and Total Croatia News. That requires some really steady nerves (the uhljeb story, I mean). Respect. Hope I will be able to get to your Nirvana stage someday soon. :)

In conclusion, please find attached 'the novel', I mean my article: Challenge accepted: let's talk the horrors of Croatian language. I do not expect you to publish it. You can just read it, since I am under the impression you value these things. If you do want to publish it, I will not mind. However, it is going to need some good editing (and cutting probably). Mother tongue interference is strong with this one.

Anyhow, I hope it will be at least somewhat useful to you, as was your video to many Croats and me personally.

Apologies for the length of the document. I just do not know when to shut up.

Kind regards,

Anamarija

CHALLENGE ACCEPTED: LET'S TALK HORRORS OF THE CROATIAN LANGUAGE

Recently I came across a YouTube video by Paul Bradbury, whom I basically know for sharing probably the same ''passion'' towards the Croatian National Tourist Board as I do. The video was related to language matters, not the legal and uhljeb ones. To cut a long story short, I really appreciate what he is doing for Croatia and its tourism, so I accepted his challenge and decided to write a piece on 20 mistakes non-native speakers (and not only them) make when speaking Croatian. To be quite honest, probably 90% of the listed mistakes are made by the majority of Croatians too. Anglicisms and pseudo-anglicisms are all the rage nowadays, but that is a completely different story. As Paul put it: if you know English, you'll do well in Croatia. Don't you ever get discouraged by something as padeži? These are not worthy of your tears.

Paul is so much more hip than I am, and he made a video. I did not make a video. Firstly because - as many others do - I hate the sound of my own voice on audio and video recordings. Secondly, I'm an old-fashioned girl. If I can make someone read in this day and age, I will do it. And I make no apologies.

Croatian is widely considered one of the hardest languages to learn for English speakers, right after Mandarin and the languages of Finno-Ugric language group. Speakers of the latter language group struggle with an even greater number of grammatical cases than we do. Imagine that horror!

Here are some practical language tips on how to excel in Croatian and avoid some common mistakes. So common that a significant percentage of Croatian people aren't aware of making those mistakes either.

1. Shall we start with light and trendy topics? Let's talk about THE beverage: pivo/beer!

So is it piva or is it pivo? The only correct form is pivo. I can understand how fond some men are of both beer and female gender so they use every possible occasion to draw comparisons between these two, even if only by playing with grammar matters. However, grammatical gender is something you cannot change, not even in the 21st century. Pivo is of neuter gender, not the female one (piva) and that is a fact. To all the men out there: you are no less a man if you address it in the neuter gender.

2. The right to enjoy one's beer in peace can be considered a matter of human rights, don't you agree? Well, among non-native speakers, human rights are often translated in Croatian as čovječja prava. Hard to believe it since you literally need to break your tongue to pronounce it, huh? This is, however, a literal translation from English. The only correct form in Croatian is ljudska prava (derived from the noun ljudi = people).

3. When someone buys you a beer, it is appropriate to thank him/her. So, you'll probably say something like hvala lijepo….And that is awfully polite of you, but is not correct in Croatian. You should always say hvala lijepa (because hvala is of female grammatical gender).

4. Let's stick to means of expressing our gratitude for a little while. This one is hard to grasp, even for Croatians. It makes all the difference in the world whether you will zahvaliti or zahvaliti se. E.g. When someone offers you a gift, there are two possible scenarios, and in both, you can use either zahvaliti or zahvaliti se. When you decide to accept the gift and express your gratitude, you will most likely say something as: zahvaljujem, divno od tebe/thank you, that is so lovely of you. However, if you decide to politely decline it, you will most probably say: zahvaljujem se, ali ne mogu to primiti/ thank you, but I cannot accept it. Also, when you're firing someone, and you want to gently deliver the news, but you don't have a cute niece around you to sing a Frozen tune along (bad joke, I know), you will use the following wording: nažalost, moram vam se zahvaliti/ I regret to inform you…

5. Now on homographs and homophones and context (they have nothing to do with your sexual orientation… or they might, who knows). So what does it really mean kako da ne? Does it mean yes, of course or the hell no? Knowing the difference makes all the difference. But the trick is: it can mean both. I can understand how people get lost in translation so easily with this one. The trick is to pay attention, depict the pitch of the voice and observe the face. If you have a Grouchy Smurf in front of you, it's probably a hell no. If you get a smiley face, or even doubled kako da ne, kako da ne, you got yourself a definite yes, sir/madam.

6. And now to make things complicated. Padeži give us hell. I know. But, one of the seven musketeers is especially avoided amongst non-native speakers of Croatian, and it is an instant traitor. It's the vocative. It's wrong to say: Ej, Ivan!/Hey, Ivan or Ivan, dođi ovamo/ Ivan, come over here. Instead, you should say: ej, Ivane and Ivane, dođi ovamo. Vocative asks for a suffix. There are exceptions, however. Of course, there are. Those exceptions are names such as Ines, Nives, Karmen etc.

In this article, I am discussing mainly spoken language, but there is one other distinction in written language when speaking of vocative: it always comes separated with a comma.

7. To stick to names, let us discuss possessive adjectives. This is a huge mother tongue interference from English. One should never say prijatelj od Stipe. You say Stipin prijatelj/ friend of Stipe. Using the preposition od + genitive form is not in accordance with Standard Croatian. Thus, you should always use a possessive adjective instead.

8. How about svoj versus moj? In Croatian, belonging to a subject is expressed through the possessive-reflexive pronoun svoj, roughly translated as one's own. Some call it a super possessive pronoun. That's how we roll in Croatia. So, if you want to say: I am going to my apartment, the wrong way to put it would be Idem u moj stan (although moj means my). Instead, say: idem u svoj stan.

This is an extremely common mistake even amongst native speakers, so don't get discouraged if it takes time for you to develop natural language processing.

9. English loves the passive voice. However, Croatian not so much. Why is that so? Probably because we like to be acknowledged, involved and informed of who did what #MiHrvati. Thus, in English it is normal to say the complaint was made by the employees, but it is not natural to say podnesena je žalba od strane zaposlenika (which you can hear a lot in administrative language amongst uhljebs). Instead, say: zaposlenici su podnijeli žalbu. Just not to make us rack our brains over who did what. Work smart, not hard (what an irony).

10. Okus and ukus. I know! You have to pucker up your lips out there to pronounce it just to end up looking like a fish and ultimately find out you opted for the wrong one. But, it is as simple as it gets. Yet, it gets interchanged way too often. Okus is used when referring to flavour and ukus denotes taste, as in a person's implicit set of preferences. You have good taste = imaš dobar ukus. Saying to someone imaš dobar okus would imply you're a bit more than friends.

11. Changing the subject. So, which team are you: team more or team voda? Have you already found yourself in a situation where you almost felt verbally assaulted by a Dalmatian explaining it to you: it's not water, it's the sea. Potato potato if you asked me. From a linguistic and scientific point of view, you are not wrong. Seawater is still water, just not the drinking type. But sometimes you cannot rationalise things with the people of Dalmatia. So, how to proceed with this one? However you want. This is 'the mistake' that is actually not a mistake per se. It is a battle you cannot win. I gave up fighting a long time ago (don't tell anyone, I have Herzegovinian roots, so I have no right to vote on this one). Yet, I boldly go where only Herzegovinians and the good folks of diaspora have gone before and I get to choose. Sometimes I enter the water, sometimes I enter the sea.

12. Let us shortly get back to grammatical cases again. Of all the cases in Croatian, instrumental is probably the easiest and most logical to learn amongst non-native speakers. However, there is something where most of them stumble. To preposition or not? It should be easy: 1) when instrumental is used in the context of explaining a tool or the means used to accomplish an action, you must leave out the preposition; 2) when talking about company and the unity of 2 entities, you will most definitely need a preposition. Thus: pišem olovkom/ pišem s olovkom (I am writing with a pencil), putujem autobusom/ putujem s autobusom (I am traveling by bus) BUT Putujem s Barbarom (I am traveling with Barbara) and volim palačinke sa sladoledom (I like crepes with ice cream).

13. Vi ste došla. Croatian is already complicated enough, so let's not complicate things where they are quite so simple. When addressing someone informally you need to pay attention to grammatical gender. However, this is not the case when using the formal Vi form. The ending is always the same both for female and male grammatical gender. Gospodine Smith, vi ste došli/ Gospodine Smith, vi ste došao. Gospođo Smith, vi ste došli. Gospođo Smith, vi ste došla.

14. Ukoliko/ako = if: you shall not break your tongue in vain! Save your breath. First, I hear you on how hard it is to pronounce ukoliko. Good news is: it's a common mistake to misuse ako and ukoliko among native speakers as well. The secret to forcing usage of ukoliko lies in the fact it sounds more erudite. However, ukoliko must be used only in combination with utoliko. In all other cases, you should use ako. They practically mean the same thing. Ukoliko ti plaćaš, utoliko idemo na kavu. Ako ti plaćaš, idemo na kavu. If you're paying, we'll have coffee. To conclude: when in doubt, use ako.

15. The next point is strictly a spelling matter. There is a distinctive difference between writing down numbers in Croatian and in English. There is no such thing in Croatian as a decimal point (used to separate a whole number from the fractional part of the number). Instead, we use a decimal comma. Thus 67.8 EUR or 67,8 eura. When it comes to small amounts, it does not seem like a big deal. However, when talking big money, it can make all the difference in the world. Write wisely.

16. When it is not padeži time, it is glasovne promjene time. Both can be summed up as headache times. But there are things you just have to learn and learning is a long and painful process.

- Sibilarizacija, known as Slavic second palatalization, is the sound change where k, g and h when found before i develop into c, z, s.

Why is this important to us? Because this is the reason why it is wrong to say u ruki mi je, instead of u ruci mi je (it is in my hand).

- Slavic second palatalization is a sound change where k, g h when found before e develop into č, ž, š.

In practical usage, it means it is wrong to say hej, momak/ hey, boy. Do not get fooled by the Dalmatian dialect where you probably hear ej, momak a lot. This is due to the fjaka state of mind. Everything is a bother, even using sound changes. Instead, steal the show and say hej, momče.

17. I know this is already a lost battle, but I am using every possible occasion to beg you: please, do not use the term event when speaking Croatian. If Croatians want to sound important, let them be. However, the original Croatian word for the megapopular event is događaj or događanje. I know it is painful to pronounce it, but I want you to know that for each time you use the term događaj instead of event, someone on this side of the screen will love you more. In case of public writing, the love doubles. Cross my heart and hope to die.

18. It's Christmas time. It's welcome parties time. Many are heading to the capital of Croatia these days. In colloquial language, it is popular to say idem za Zagreb (I am going to Zagreb). However, this is wrong. You should always say: idem u Zagreb. Motion verbs ask for the preposition u instead of the preposition za (preposition u > preposition za).

19. I know the Italian language sounds more romantic, but when you order prosecco in Croatia - you get bubbles. If you want to try an indigenous product, ask for prošek. Many confuse Prosek with Prosecco due to a lost in translation moment. However, the difference is major. Prošek is a thick and syrupy still dessert wine. Thus, do not worry about translation and the labels of the protected designations of origin and just taste it. Enjoy the simplicity.

20. Ah, I saved the last dance for you. There is a popular opinion that the usage of particle/conjunction groups da li and je li is a matter of major distinction between the Croatian and Serbian languages. This is not necessarily the case. However, the usage of the group da li is not in accordance with the normative rule of Standard Croatian. Thus, to form an interrogative sentence, you should opt for verb + particle li (commonly known as je li group) instead of da li. E.g. Da li je to restoran o kojem si mi pričao? Je li to restoran o kojem si mi pričao. However: Da li me voliš? Voliš li me?

You have my respect If you managed to reach the end of the article. Go reward yourself with one pivo now. All jokes aside, Croatian has many dialects and sub-dialects. Many non-native speakers learn the language from online sources created by Croats in the diaspora (where the majority did not learn Standard Croatian) or from locals using the dialect. There you have a root for all the above-mentioned mistakes.

Also, the trait of the Croatian language is that it is rather liberal, more descriptive than prescriptive in nature. For this reason, it does not have one official orthography. Instead, there are many unofficial editions. However, the recommendation is to choose one and aim at consistency.

For all that has been said, do not ever get discouraged by making mistakes. We all make them. Bear in mind one significant difference: it is easier to learn English nowadays with all the variety of learning tools and sources out there. To learn Croatian as a non-native speaker is a true stunt. An admirable one. Do not give up.

****

Wow, thanks Anamaija - I certainly learned a few things (and am still recovering from someone writing a 3,000 word response to one of my videos). I asked Anamarija to tell me a little about her. If you want to contact her, let me know on This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and I will pass on your details.

My name is Anamarija (full name: Anamarija Pandža) and I live in Omiš, the stunning small town I am incurably sentimental about.

I am 50% English to Croatian human translator/ court interpreter/ proofreader/ content writer/ entrepreneur and 50% coffee. Coffee and the sea are the only 2 things I cannot live without. That is, I can - but I choose not to. I'm also a huge fan of words. They are my playground. I use quite a lot of them, both for making a living and to rant for the sake of ranting.

You will find me at the kids table. Always. Utopist. Forever smiling Grouchy Smurf. Forever waiting for a Godot. Also, forever a black sheep wherever I go. In love and hate relationship with this country and its people.

The worst and the best thing you can do is to tell me to give up. That is when the game begins. I never give up. This is why I chose not to give up on Croatia either.

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning - Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Subscribe to the Paul Bradbury Croatia & Balkan Expert YouTube channel.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners is now available on Amazon in paperback and on Kindle.

From Czech to Ruthenian - Minority Languages in Croatia

December the 19th, 2022 - Minority languages in Croatia are either given no attention or are quite controversial, and with such a rich and tumultuous history which involves some of their speakers, some are given more rights under the Croatian Constitution than others.

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian.

What about minority languages in Croatia, though? While some of the above might seem as if they themselves are minority languages, with so much controversy about whether they're languages or mere dialects has unfortunately caused many to not even be given a proper protected status. It's true that some are even on UNESCO endangered languages list, but they're still not categorised by the Croatian powers that be in the same way that the likes of Czech, Hungarian or Slovakian are in this country.

Let's look into what exactly is deemed to be a minority language in Croatia and how that functions within the Croatian Constitution.

Minority languages in Croatia are the mother tongues (first languages) of national and ethnic minorities living across modern Croatian territory. In addition to personal and intra-community use, minority languages in Croatia are used in different ways and to varying extents in both official and public areas.

The Croatian Constitution defines the Republic of Croatia as the nation of the Croatian people, the country which belongs to all its citizens, including traditional autochthonous communities, which the constitution refers to as national minorities. The minorities explicitly listed in the constitution are; Serbs, Czechs, Italians, Hungarians, Slovaks, Jews, Germans, Ukrainians, Ruthenians, Austrians, Bosniaks, Slovenes, Macedonians, Russians, Montenegrins, Bulgarians, Poles, Romanians, Turks, Roma, Vlachs and Albanians.

Article 12 of the Croatian Constitution states that the official language in Croatia is what we now call standard Croatian, while for some local self-government units (cities and municipalities) another script may be introduced into official comparative use.

Now we've seen who the national minorities are, how do minority languages in Croatia stand under the law?

The use minority languages in Croatia is regulated on the basis of competent national laws, international conventions and agreements which the country has signed. The most important laws at the national level are the Constitutional Law on the Rights of National Minorities, the Law on the Use of the Language and Script of National Minorities and the Law on Education in the Language and Script of National Minorities. The most important international agreements related to minority languages in Croatia are the European Charter on Regional or Minority Languages and the Framework Convention on the Protection of National Minorities adopted by the Council of Europe. The members of national minorities have acquired certain rights in this country over time through interstate and international treaties and agreements, such as the Erdut Agreement and the Rapala Treaty.

It's unfortunate to say but must be said regardless, that the Croatian public and in many cases the authorities don't always have much of a positive attitude towards issues experienced by minorities in this country, and as such minority rights, but Croatia's EU membership has had an overall very positive impact on the affirmation of the official use of minority languages in Croatia, and things in that respect continue to stabilise as time goes by.

There are several Croatian municipalities in which what are deemed to be official minority languages are spoken today.

German

The National Association of Danube Swabians, which is the largest minority association of the German Community, strongly advocates for German language use in the Eastern part of the country, particularly in and around Osijek where it holds a form of traditional status. In modern Croatia, spoken German is primarily the first or second foreign language someone has, and it is also recognised as the official minority language of both Germans and Austrians living in Croatia.

Czech

Over 6000 people living in the continental Croatian county of Bjelovar-Bilogora have declared themselves to be members of the Czech national minority. 70% of these individuals say that Czech is their mother tongue. Back in 2011, MP Zdenka Cuhnil pointed out that based on their acquired rights, the Czech minority in Croatia has the right to equal use of the language (alongside standard Croatian) in nine local self-government units.

Ruthenian

The Ruthenian dialect spoken in both Vojvodina and modern Croatia became standardised back during the first half of the 20th century, with Ruthenian publications having been being published since the 1920s. While in Ukraine, the Ruthenian community isn't officially recognised as being a separate nation, minority status and language rights outside of Vojvodina and Croatia were recognised and began to develop only in the post-Cold War period.

The Ruthenians living in the area of Eastern Slavonia don't differ from the Ruthenians living in Vojvodina culturally or linguistically. It is worth noting however that Ruthenian spoken in this area does differ from the speech of other Ruthenian communities located elsewhere, and is characterised by a significant number of loanwords from Croatian as we know it today. The use of the Ruthenian language on the whole began to decline after the Second World War, and the process accelerated even more following the end of the Homeland War (Croatian War of Independence).

Romany (Roma language)

While the Croatian Parliament formally recofnised the Day of the Roma Language (May the 25th) back in 2012, the Central Library of Roma in Croatia, which is also the only Roma library in all of Europe, was on;y opened back during the summer of 2020, so not long ago at all when you consider the length of time the Roma people have been present in this country and the wider region. The Roma people are among those who experience a lack of help when it comes to the authorities, and issues between this community and the general public are rife for a multitude of reasons.

Slovakian

A magazine called Pramen is published in the Slovakian language by the Union of Slovaks in Croatia. This was achieved thanks to cooperation with the Slovak Cultural Centre (located in Nasice). Back in 2011, over 500 students in the Eastern part of the country were taught Slovakian twice per week from the first grade of elementary school onwards.

Ukrainian

The Ukrainian community present in Croatia publishes the following publications in the Ukrainian language - Nova Dumka, Vjesnik, Nasa Gazeta, Vjencic (aimed at kids) and Misli s Dunava. Since way back in 2001, the Department of Ukrainian Language and Literature has been in function at the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Zagreb. Following the outbreak of war in Ukraine following shock Russian invasion back in February 2022, Ukrainian presence has been far stronger in Croatia thanks to its very welcoming stance towards Ukrainian refugees fleeing Russian onslaught in their homeland. As a result, it's likely that the language will be heard much more.

Hebrew and Yiddish

The library of the Jewish Municipality of Zagreb actually doesn't (yet, anyway) have the status of one of the central minority libraries of Croatia. In addition to the library in Zagreb, the Hugo Kon Elementary School, founded in 2003, is also in operation. The Festival of Tolerance - The Jewish Film Festival was founded back in 2007 by the well known Branko Lustig with the aim of preserving the memory of those lost during the Holocaust and promoting tolerance going forward so that such horrors are never repeated.

Hungarian

When it comes to higher education institutions in Croatia, Hungarian can be studied at the University of Zagreb, the Josip Juraj Strossmayer University in Osijek, and most recently at the University of Rijeka. To turn the wheels of time back a little, it's worth remembering that much of Croatian territory was once under the reign of the former Austro-Hungarian empire, and aside from being our neighbours, Hungary and as such Hungarian language has had quite the influence on this country over the centuries. Now classed as one of the official minority languages in Croatia, Hungarian has been advocated for in many ways here. Back in 2004, representatives of the Hungarian national minority called for the introduction of Hungarian into official use in Beli Manastir, referring to the rights acquired by Hungarian nationals before 1991 and the complications which arose due to the outbreak of war. In the same year (2004) the Hungarian minority made up 8.5% of Beli Manastir's resident population.

Italian

I've written numerous articles on the array of dialects and subdialecs spoken across the Istrian peninsula, most of them deriving in some way from Venetian. These dialects (and some linguists would argue them to be languages in their own right) come from the complex and very long history Italy and Istria share, as the two are deeply historically, culturally and as such linguistically enmeshed. As such the Italian minority in Croatia achieved a significantly wider right to use their own language than all other minority communities in the country. La Voce del Popolo is a daily newspaper published in the Italian language that is published in Rijeka. On top of that, we also have the likes of Istro-Venetian, which is sparsely spoken in comparison to standard (modern) Italian, and you can learn more about it here.

Serbian

By far the most controversial of all, and for obvious reasons, is the Serbian language as one of the Croatian minority languages. I probably don't need to go into the ins and outs of why it is controversial in comparison to the others, as that would be an article of its own. Instead, I'll just list some facts.

Education in Serbian was made possible in the territory of the former self-proclaimed Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and western Srijem on the basis of the aforementioned Erdut Agreement, which created the preconditions for the peaceful reintegration of the Croatian Danube region. In this region, teaching is conducted according to Model A of minority education, in which the entire teaching takes place in the language and script of national minorities - in this case it is Serbian. Schools in Podunavlje, for example, do organise classes in Croatian or in another minority language if the minimum number of students to enroll in a class according to a certain model are present.

Critics see the continuation of the Croatian-Serbian conflict in the Danube region in the model of divided classes, while the official representatives of the Serbian minority see the negative attitude towards the Serbian departments as pressure in the direction of denationalisation. In either case, the use of the Cyrillic script on road signs, on buildings and indeed elsewhere in parts of Croatia which were ravaged by Serbian onslaught back during the nineties are far from popular and have remained a burning issue ever since the Homeland War drew to a close.

Of the other languages, one which is sadly dying out at an alarming rate is the Istro-Romanian language, which is listed in UNESCO's own Red Book of Endangered Languages as seriously endangered. With Istro-Romanian likely to follow the same path as Istrian-Albanian and become extinct within the next few decades, if not sooner, little is being done to preserve it for generations to come.

For more on Croatian languages, history, minority languages and dialects, follow our lifestyle section.

Words Without Sound - A Brief Look at Croatian Sign Language

December the 12th, 2022 - Croatian sign language is the one language spoken in Croatia which of course has no sound to the words, but did you know that there's no clearly defined number of people living in Croatia who use it?

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje and Medjimurje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian.

There are known or at the very least educated guesses as to how many individuals speak most of the aforementioned languages. Of course, some, such as Istrian-Albanian, a form of Gheg (Geg) Albanian once spoken in Katun, are now extinct. Others, such as Istro-Romanian, are on UNESCO's severely endangered language list with very good reason. As stated, there is no firmly known number of people who use Croatian sign language, but it has been defined as an independent language system in and of itself. This means that it has its own rules surrounding grammar which have nothing to do with those used by hearing individuals.

Back in 2015, the Law on Croatian Sign Language and Other Communication Systems of Deaf-Blind Individuals in Croatia was passed, and now courses teaching this language are more or less commonplace in all larger Croatian cities. It is even taught as part of higher education, with university-level Croatian sign language being taught as different courses for undergraduate speech therapy students. This is mandatory.

Naturally, although their exact number remains unknown, the overwhelming majority of those capable and competent in Croatian sign language are members of the deaf or hard of hearing community living in Croatia, and the associations formed by and for them are some of the main bodies which hold classes and courses.

Some of those Croatian associations for the deaf and the deaf-blind are Savez gluhih i nagluhih grada Zagreba (The Association of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing of the City of Zagreb), Dodir (Touch), Kazaliste, and audiovizualne umjetnosti i kultura Gluhih – DLAN (Theatre, audiovisual arts and the culture of the Deaf).

For more on Croatian language, dialects and subdialects spoken across the country, as well as this history of language in this country, make sure to keep up with our dedicated lifestyle section.

Exploring Croatian - A Brief History of the Istro-Romanian Language

November the 28th, 2022 - Have you ever heard of any Balkan-Romance languages other than Romanian? Unless you happen to be a linguist, the term is probably somewhat alien to you, especially given the fact that the languages spoken across much of the region (but not all of it) are Slavic. Let's get better acquainted with the sparsely spoken Istro-Romanian language.

We've explored many of the dialects, subdialects and indeed languages in their own right as some linguists consider them to be which are spoken across modern Croatia. From the Dubrovnik subdialect (Ragusan) in the extreme south of Dalmatia to Northwestern Kajkavian in areas like Zagorje, the ways in which people speak in this country deviate from what we know as standard Croatian language enormously. That goes without even mentioning much about old Dalmatian, Zaratin, once widely spoken in and around Zadar, Istriot, or Istro-Venetian.

Istria in particular is full of culture, and its rather complex historic relationship with Italy and in particular with the formerly powerful Venice has a lot to answer for in this regard. That brings us to a language that actually has nothing to do with Venetian, and is only spoken by people who call themselves Rumeni or sometimes Rumeri. It can only now be heard in very few rather obscure locations and with less than an estimated 500 speakers of it left, the Istro-Romanian language is deemed to be seriously endangered by UNESCO's Red Book of Endangered Languages.

Who are the Istro-Romanian people?

The Istro-Romanians are an ethnic group from the Istrian peninsula (but they aren't necessarily native) and they once inhabited much of it, including parts of the island of Krk. It's important to note that the term ''Istro-Romanian'' itself is a little controversial to many, and most people who identify as such do not use the term, preferring instead to use the names taken from their villages. Those hamlets and small settlements are Letaj, Zankovci, the wider Brdo area, Zeljane, Nova Vas, Jesenovik, Kostrcani and Susnjevica.

Many of them left to begin their lives in either larger Croatian cities or indeed in other countries as the industrialisation of Istria in the then Yugoslavia progressed at a rather rapid pace. Following Istrian modernisation which had enormous amounts of resources pumped into it by the state, the number of Istro-Romanian people began to dwindle rather significantly, until they could only really be found in a handful of settlements.

The origins of the Istro-Romanian people are disputed, with some claiming they came from Romania, and others claiming that they arrived originally from Serbia. Regardless, they have been present in Istria for centuries and despite efforts from both the Romanian and Croatian governments to preserve their culture and language - the Istro-Romanian people are still not classed as a national minitory under current Croatian law.

Back to the Istro-Romanian language

Like many dying languages, the Istro-Romanian language was once much more widely spoken across the Istrian peninsula, more precisely in the nothwestern parts near the Cicarija mountain range. There are two groups of speakers despite the fact that the language spoken by both is more or less absolutely identical, the Vlahi and the Cici, the former coming from the south side of the Ucka mountain, and the latter coming from the north side.

Back in 1921, when the then Italian census was being carried out, 1,644 people claimed they were speakers of the Istro-Romanian language, with that figure having been deemed to actually be around 3,000 about 5 years later. Fast forward to 1998, the number of people who could speak it was estimated to stand at a mere 170 individuals, most of them being bi or trilingual (along with Croatian and Italian).

The thing that will be sticking out like a sore thumb to anyone who knows anything about language families - the fact that this is called a Balkan-Romance language. While it is classified as such, the Istro-Romanian language has definitely seen a significant amount of influence from an array of other languages, with approximately half of the words used drawing their origins from standard Croatian as we know it today. It also draws a few from Venetian, Slovenian, Old Church Slavonic and about 25% or so from Latin.

Istro-Romanian is very similar to Romanian, and to anyone who doesn't speak either but is familiar with the sound, they could easily be confused. Both the Istro-Romanian language and Romanian itself belong to the Balkan-Romance family of languages, having initially descended from what is known as Proto-Romanian. That said, some loanwords will be obvious to anyone familiar with Dalmatian, suggesting that this ethnic group lived on the Dalmatian coast (close to the Velebit mountain range, judging by the words used) before settling in Istria.

Most of the people who belong to this ethnic group were very poor peasants and had little to no access to formal education until the 20th century, meaning that there is unfortunately very little literature in the Istro-Romanian language to be found, with the first book written entirely in it having been published way back in 1905. Never used in the media, with the number of people who speak it declining at an alarming rate and with Croatian (and indeed Italian) having swamped Istria linguistically, it's unlikely you'll ever hear it spoken. Some who belong to this ethnic group who live in the diaspora can speak it, but that is also on a downward trajectory.

This language has been described as the smallest ethnolinguistic group in all of Europe, and without a lot more effort being put into preservation, the next few decades to come will almost certainly result in the complete extinction of the Istro-Romanians and their language.

For more on the Croatian language, dialects, subdialects and history, make sure to check out our dedicated lifestyle section.