People Also Ask Google: What Language Do They Speak in Istria?

February 25, 2021 – Continuing the TCN series answering the questions posed by Google's People Also Ask function, one that confuses many: what language do they speak in Istria?

Where is Istria?

Istria is the biggest and northernmost peninsula in Croatia and the Adriatic. It lies in the northern part of the Adriatic, in Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy. Geographically, 90 percent of the Istrian peninsula is part of Croatia, while nine percent includes Slovenia.

Most Croatians live in the Croatian part of Istria (68,33 percent), while minorities make up a quarter of the population, of which Italians are the biggest group – six percent. In the Slovenian part, Slovenes make up the absolute majority population. Only one percent of the Istrian surface is part of Italy. It includes only two small municipalities near Trieste, of which the majority of the inhabitants in one are Slovenes and in the other are Italians.

According to the 2011 census, 25 percent of people in Croatia declared their regional identity as Istrian, of which 12 percent live in Istria County, one of 20 Croatian counties. The name for a regional identity developed by a part of the citizens of Istria, mainly its Croatian part, is Istrianism. Thus, regional identification is more pronounced in Istria than in other parts of Croatia.

How many official languages are there in Istria?

Since there are two official languages in Istria – Croatian and Italian – Istria is a bilingual community. Italian is the second official language in Istria since 1994, and the Constitution guarantees the rights to bilingualism in Croatia. Out of 208,000 inhabitants in Istria County, 180,000 stated that their mother language was Croatian, while 14,000 of them stated Italian as their mother language.

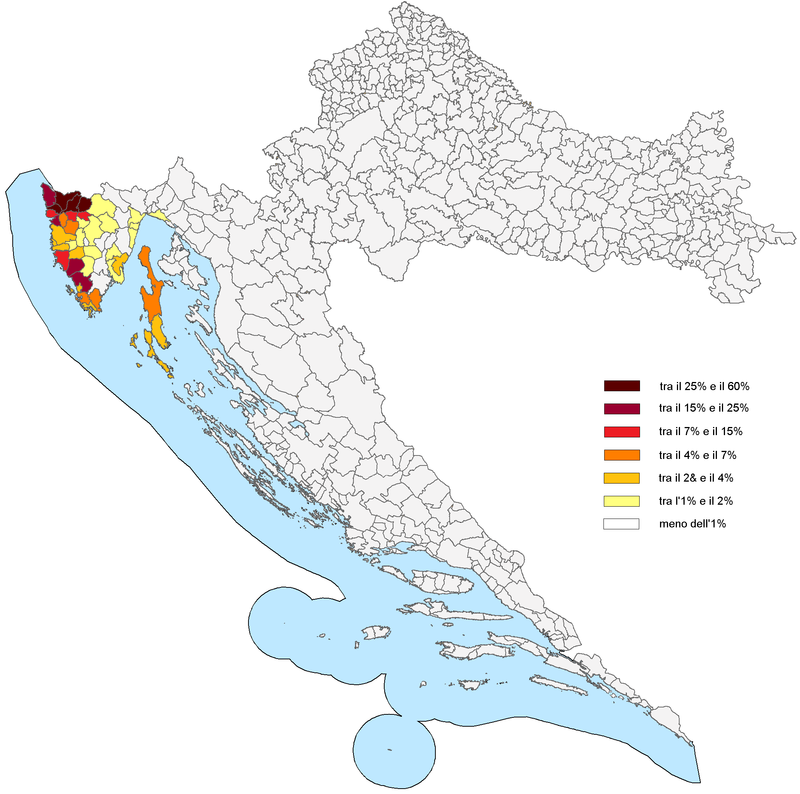

Native speakers of Italian in Croatia according to the 2011 census / Wikipedia

In addition to Croatia's Constitution, local legislation, i.e., the Istrian County Statute equates these two languages in public use and encourages learning Italian as an environmental language. The Istrian bilingual community includes both smaller and larger Istrian settlements.

Due to this bilingualism, Istria is a specific region in Croatia, so there are many Italian public institutions (schools, kindergartens, etc.). Istria has a long tradition of education in another language. Besides, the environment itself is bilingual, which means that Italian is not only spoken by Italians but people of other nationalities too, including Croatians. Also, Istria is historically, culturally, and economically strongly connected with Italy.

Buje, Istria / Copyright Romulić and Stojčić

Reputable cultural, scientific, pedagogical, and artistic minority institutions have been established in Istria: Italian Drama in Rijeka (Dramma Italiano), Center for Historical Research in Rovinj (Centro di Ricerche Storiche), Italian department at the Faculty of Philosophy and departments in Italian for teacher education at the College of Teacher Education in Pula. Also, La Voce Del Popolo, a daily newspaper in Italian owned by the Italian Union (Unione Italiana), is published in Rijeka.

During his visit to Istria last year, Italian Ambassador to Croatia, Pierfrancesco Sacco, said that Italians in Croatia feel at home, like Croats in Italy. This is especially evident in Istria and Pula, where there are a deep friendship and a desire to find new cooperation methods. On that occasion, the Mayor of Pula, Boris Miletić, said that the fundamental values, which have been nurtured in this area for decades, are openness, multiculturalism, and coexistence.

What language do they speak in Istria?

The vast majority of Istrians speak the Croatian language's Chakavian dialect, meaning they use the interrogative pronoun "ča." Only in some parts near the border with Slovenia, some people use the interrogative pronoun "kaj," so they are often mistaken for Kajkavians. Still, the structure and characteristics of these speeches are distinctly Chakavian.

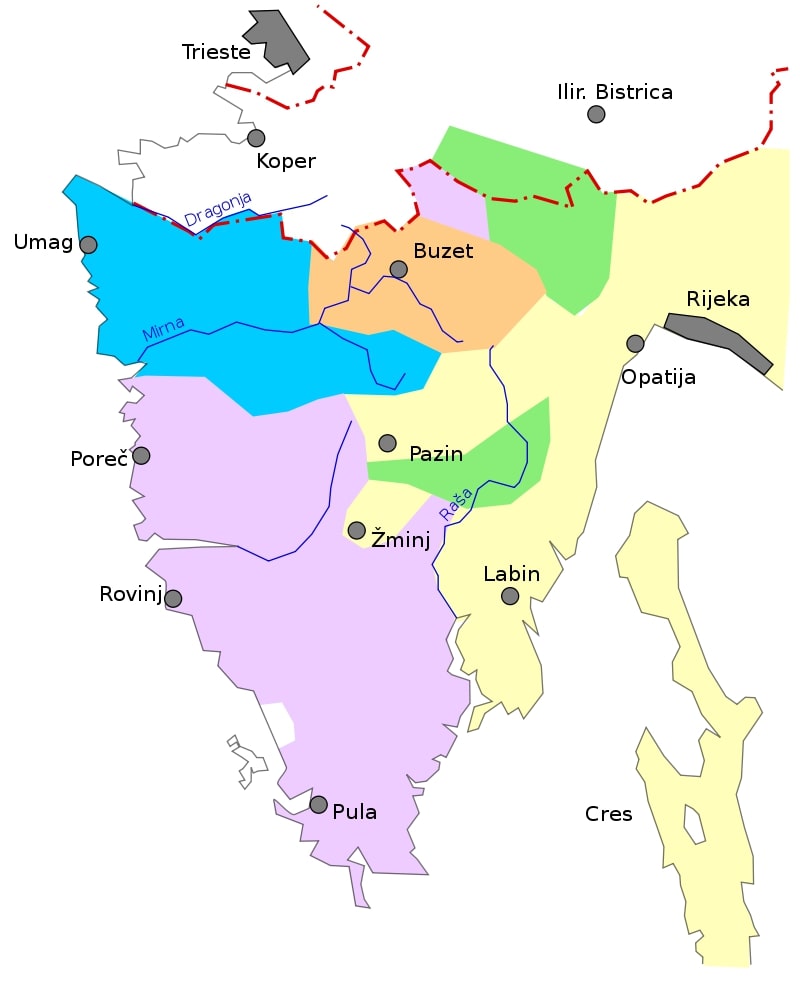

Chakavian dialect is also spoken in Dalmatia. However, the Istrian Chakavian dialect is different from the Dalmatian one due to the numerous Italianisms. It is also difficult to understand it in the rest of Croatia. The most widespread Chakavian dialect in Istria is the Southwestern Istrian dialect. There are also Buzet, Northern, Central, and Southern Chakavian dialects in Istria.

Chakavian dialects in Istria: Southwestern (purple), Buzet (orange), Northern (yellow), Central (green), and Southern Chakavian (blue) / Wikipedia

The aforementioned Italian minority lives in some towns on the Istrian west coast and in some villages near Buje, and they speak Italian. In the Slovenian part of Istria, the Slovenian language is spoken.

In the eastern part of Istria, at the foot of the Ćićarija mountain, in several smaller villages live Istro-Romanians or Ćići, a population of Romanian origin who speak their own Istro-Romanian language, which is a mixture of Romanian and Croatian. Today, many of them have adopted the Croatian language and are now considered Croats.

In addition to the dominant Croatian and Italian languages, other minority languages are spoken in Istria, namely Serbian, Bosnian, Slovenian, Albanian, and Macedonian. One can hear the Shtokavian dialect in Istria as well.

What language do they speak in Istria? Istro-Romanian language

Istria is home to two of the 20 most endangered languages in the world by UNESCO – the Istro-Romanian language and Istriot.

Istro-Romanian language is a Balkan Romance language spoken by only a few hundred people today in the northern Istrian villages of Žejane, Lanišće, and Šušnjevica. It is highly similar to the Romanian language, and for some linguists, the Istro-Romanian language is considered a dialect of Romanian. People in Istria who speak it are called Rumeri, Rumeni, Vlachs, or Istro-Romanians. Croats disparaging started to call them Ćići or Ćiribirci.

In the middle of the 15th century, the Ćiribirci were settled by Ivan VII Frankopan from Velebit on the island of Krk. Since the Ćići plundered Ivan Frankopan in northern Istria in 1463, when their name is first mentioned, it is believed that they immigrated to Istria from Krk. However, Istro-Romanians are not officially recognized as a national minority in Croatia.

The most interesting fact about the Istro-Romanian language is that it was spoken by one of the most famous inventors of all time – Nikola Tesla – even though he wasn't even aware of the ethical existence of the Istro-Romanians. Since elementary school, Tesla was able to speak the Istro-Romanian language, despite the fact that Istro-Romanian was not taught in schools in those years. It was only spoken by a few thousands of people in Istria and Lika, and he could have probably learned it in his family.

Although Telsa always considered himself a Serbo-Croat, one Romanian academic, Professor Moraru, thought Tesla was an Istro-Romanian. When Romanian scholars contacted Tesla in the early 20th century and explained he was of Istro-Romanian roots, he allegedly showed amazement but did not comment on that matter. Therefore, Nikola Tesla has never denied the possibility of his Istro-Romanian origins.

What language do they speak in Istria: Istriot language

Istriot language, often confused with Istro-Romanian language, is a Romance language spoken by about 400 people in the southwestern part of Istria, particularly in Rovinj and Vodnjan. Still, it is also preserved in Bale, Fažana, Galižana, and Šišan. It should not be confused with the Istrian dialect of the Venetian language either.

According to some estimates, the Istriot has only a few dozen active speakers and about 300 people who understand it and can use it in part. It is a Romance language related to the Ladin populations of the Alps, currently only found in Istria. Its classification remained mostly unclear, but in 2017, it was classified with the Dalmatian language in the Dalmatian Romance subgroup.

Historically, its speakers never referred to it as "Istriot language." Instead, it had six names after the six towns where it was spoken: in Vodnjan it was named "Bumbaro," in Bale "Vallese," in Rovinj "Rovignese," in Šišan "Sissanese," in Fažana "Fasanese," and in Galižana "Gallesanese." The term Istriot was coined by the 19th-century Italian linguist Graziadio Isaia Ascoli.

Younger Italians in these places mostly understand Istriot, but they rarely use it, and Croats rule this idiom very badly or not at all. It is most endangered in Fažana, and it seems that it is most strongly maintained in Bale.

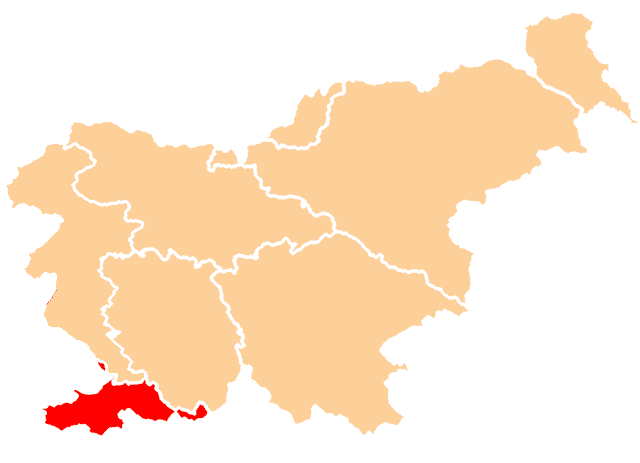

What language do they speak in Istria: Istrian dialect in Slovenia

Slovene dialects are separated into a few groups, and the Istrian dialect, spoken in Slovene Istria, falls in the Littoral dialect group. Istrian dialect is spoken in the rural areas of Koper, Izola, and Piran. The Slovenes living in the Italian municipalities of Muggia and San Dorligo della Valle, as well as in the southern suburbs of Trieste (Servola, Cattinara). In Croatia, it is also called the Slovenian-Istrian dialect.

The dialect has been influenced by Croatian as spoken in Buzet and Ćićarija and is further subdivided into the Rižana and Šavrin Hills subdialects.

Slovene Istria / Wikipedia

Rižana subdialect (yellow) and Šavrin Hills subdialect (green) / Wikipedia

The Rižana subdialect is spoken in the northern part of Slovenian Istria, in the Rižana Valley east and north of Koper, including the settlements of Bertoki, Dekani, Osp, Črni Kal, Presnica, Podgorje, and Zazid. In Italy, Rižana subdialect is spoken in most of the municipalities of San Dorligo della Valle and Muggia south of Trieste and some southern suburbs of Trieste, especially Servola.

The Šavrin Hills subdialect is spoken in the Šavrin Hills south of a line from Koper to the south of Zazid. It includes the settlements of Koper, Izola, Portorož, Sečovlje, Šmarje, Sočerga, and Rakitovec.

The mixture of Šavrin dialects proves the closeness to the Čakavian dialects, and the Rižana sub-dialect is entirely Slovene. There are many Romance loanwords in both sub-dialects linguistic legacy, mostly Venetian, Trieste-Romance, and Italian.

Why do locals speak Italian?

As previously explained in the second paragraph of this article, Croatians in Istria speak Italian because it has been implemented in public speech and institutions for such a long time.

As Marija Črnac Rocco, head of the Rovinj City Council office, explained for Novosti portal, the Italian national minority in Istria (and certain other Croatian parts) is autochthonous, meaning that the Italian component has always lived and existed in these territories.

Likewise, Italian was the official language during all the various reigns in Istria until the end of the Second World War – the Venetian Republic, the Kingdom of Austria, Napoleon's rule, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, and the Kingdom of Italy.

Rovinj, Istria / Copyright Romulić and Stojčić

After the Second World War, Istria was annexed to the Federal Republic of Slovenia and Federal Republic of Croatia, namely the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The Italian national community's position, which became a minority in a significant part of Istria due to sad post-war circumstances, has been the subject of consideration and securing the rights of many international agreements.

Therefore, the equal use of the Croatian and Italian languages in Istrian County and many towns and municipalities in Istria is undoubtedly a legal obligation, which for most Istrians is both a moral duty and a civilizational achievement of which they are proud.

Bilingualism in Istria is not only lived in translated official documents, it is lived in families, on the street, in everyday communication, in traditions, and customs. Bilingualism in Istria is natural, spontaneous, and it is perceived as an advantage and a richness.

Istria in Italian and Croatian: some important bilingual place names

Istrian County has ten cities and 31 municipalities. When you drive through Istria, you will notice bilingual traffic signs, including both Croatian and Italian names of towns and municipalities, such as:

- Buje – Buie

- Buzet – Pinguente

- Fažana – Fasana

- Grožnjan – Grisignana

- Labin – Albona

- Medulin – Medolino

- Motovun – Montona

- Novigrad – Cittanova (d'Istria)

- Pazin – Pisino

- Poreč – Parenzo

- Pula – Pola

- Rovinj – Rovigno

- Umag – Umago

- Višnjan – Visignano

- Vodnjan – Dignano

- Vrsar – Orsera

- Žminj – Gimino

As such, in Croatian, we say Istra, and Italians say Istria.

When was Istria a part of Italy?

Istria was a part of the Kingdom of Italy after the First World War when the Austro-Hungarian Empire disintegrated. In 1920, with the Rapallo Peace Treaty, Istria, the Croatian city of Zadar, as well as the islands of Lastovo, Cres, and Lošinj, belonged to Italy. Rijeka belonged to Italy in 1924. During the Second World War, the population organized a movement of resistance to fascism by Benito Mussolini. Therefore, after the war, Istria became part of Yugoslavia, where it remained until its disintegration in the early 1990s when the Istrian peninsula was divided by Croatia and Slovenia.

During the 19th and the first half of the 20th century, a significant Italian linguistic and ethnic community in Croatia mainly concentrated on the west coast of Istria and in Rijeka, Dalmatian, and Kvarner towns. After the First and especially after the Second World War, most Croatian Italians emigrated to Italy.

Grožnjan / Copyright Romulić and Stojčić

Today, almost three-quarters of all Italians in Croatia live in Istria County. The only municipality in Croatia where Italians make up a relative majority is Grožnjan in Istria, with 39.4 percent ethnic Italians in the population and 56 percent of the people whose mother language is Italian.

The Italian community's position and rights are guaranteed by the Constitutional Law on Human Rights and the Rights of Ethnic and National Communities of the Republic of Croatia, as well as various international agreements and treaties.

To follow the People Also Ask Google about Croatia series, click here.

Month of Croatian Language to be Observed from 21 February to 17 March

ZAGREB, 20 February, 2021 - The Month of the Croatian Language starts on Sunday, and the Institute of Croatian Language and Linguistics has called on all primary and secondary schools students to tune in to its virtual Croatian language classes, to last until March 17.

The Month of the Croatian Language is taking place between the day marking the International Mother Language Day, 21 February, declared by UNESCO in 1999, and 17 March, the day when the Declaration on the Name and Status of the Croatian Standard Language was published in 1967.

"The Month of the Croatian Language has been marked in Croatia and everywhere else where Croatian is spoken for a number of years. One of the most important traits of the Croat national identity, the Croatian language has kept its identity and autonomy despite its less than favourable treatment, resisting all pressure, degrading and bans throughout its millennial history," the Institute says.

It recalls that in 2013 Croatian became the 24th official language of the European Union, which was one of the reasons why the Institute launched the Month of the Croatian Language to continue protecting the Croatian linguistic and national identity in the European family of nations.

This year's edition of the Month of the Croatian Language will be held online and will last until March 17.

It will include numerous lectures on digital platforms, whose schedule will be agreed with Croatian language teachers.

Learning Croatian: the Dialect Words of Hvar Wine (VIDEO)

January 10, 2021 - Continuing our alternative look at the Croatian language through Hvar dialects, some essential vocabulary relating to Hvar wine.

One of my favourite features over the last ten years writing about Croatia is a language series we started soon after the launch of Total Hvar way back in 2010.

Sitting in The Office in Jelsa one quiet November lunchtime, I decided to film my friend with some typical Dalmatian greetings.

The unique phenomenon that is the Dalmatian Grunt hit the Internet and a new online start was born. The linguistic colossus that is Professor Frank John Dubokovich, Guardian of the Hvar Dialects, quickly amassed 50,000 views on YouTube, and a fascinating series of lectures followed, until they were inexplicably removed from YouTube a few years ago.

Thankfully, I came across some of the offline originals recently and have been publishing them again.

Today's lesson focuses on the dialect words for Hvar wine. In some ways, it is a landmark lesson, since it was the first to be independently commissioned by someone else.

The Professor's fame had spread so far that national television came calling, and they requested that we record an exclusive lesson for them about Hvar wine for a forthcoming primetime feature on tourism in Jelsa.

The Professor was eager to please and was eager to expand his ever-expanding flock. We thought that the best place to record was at Artichoke Wine Bar and Restaurant in Jelsa, which became the first place the island to offer Hvar wine by the glass soon after it opened several years ago.

You can check out the Professor's latest foray into the world of Hvar wine above, as well as checking out the entire feature on Jelsa, the only time in my life I have ever been recorded eating blitva.

You can catch up with The Professor's teachings on our TCN Talks YouTube channel.

For more news from Hvar, check out the dedicated TCN section.

Croatian Language: Logical, Phonetic, Impossible, Dialectalised & Globalised

December 6, 2020 - Is the Croatian language as impossible to learn as they say? It really depends on how you view it. A bigger question might be whether or not locals can understand each other when they speak it.

One of the most amazing experiences I have had as a parent so far was watching my eldest daughter learn to read at the age of four.

One day, she sat with all the letters, learned what the fuss was about, how to write and pronounce them. I was really impressive and the proudest father in the country.

"Come on then, Dad, test me. Give me a word to write."

We started with simple words like 'dobar dan.' I was amazed at how quickly she produced the perfect answers. I tried something harder, the names of the towns and villages on Hvar - Jelsa, Vrboska, Pitve, Vrisnik. All perfect. Never being the most patient guy in the world, I tried something really hard - the word for patience.

S T R P LJ E N J E she wrote, without a moment's hesitation.

Incredible, but it confirmed to me what I already knew - that Croatian is a totally phonetic language. What you see is what you get. The words may look complicated, but if you learn the 33 letters and how to pronounce them, there are no surprises.

"Now can you spell the English word for 8?" I asked, intrigued. She thought for a moment:

A J T

As it should be when you learn to read and write with the Croatian alphabet as your guide. She looked at me in horror when I showed her E I G H T.

"Your language is very stupid, Daddy." You are not wrong there, kiddo.

Not only is Croatian the most phonetic language I have come across, it is also the most logical. This may surprise people, give that the Croatian language has a reputation for being incredibly difficult to learn. And I would agree that it is, if you are not versed in the structure of Slavic languages.

My baptism of fire with Slavic languages was Russian, which I studied at university in anticipation of becoming the MI6 bureau chief in Moscow. Getting a Western brain around Slavic languages after growing up on French, German, Latin and Ancient Greek took some effort, but my knowledge of the structure of Russian helped tremendously when I came to tackle Croatian. All the language structure issues were essentially the same, and it was just a case of learning the words, as well as the case endings for Croatian. All of these were totally regular once you learned about 10 execptions, all of which were applied without exception. Which mean that they were also very regular in a way.

Things like 'k' followed by 'i' always goes to 'ci' - Afrika but u Africi, and so on.

Learn the Slavic structure, those 10 or so exceptions and the Croatian alphabet, and you have the keys to the linguistic kingdom of the world's most logical language. A battle-hardened, worldly-wise Esperanto for Slavs.

Except...

There are a couple of things that get ine way of this perfect story of the harmonious Croatian language - history, dialects and globalisation being three of them.

One of my favourite little-known facts about the Croatian language is one I learned while living on Hvar. On Croatia's premier island, full-time population 11,000, there are 8 different dialect words for chisel, depending on which town or village you come from. The bigger joke back then was it was impossible to actually find a chisel even if you used all eight words.

When I started learning Croatian, I had about 6 private classes before I realised that I could teach myself the grammar after my Russian linguistic training, and pick up the vocabulary over conversation in the cafes. And all was going really well until I travelled one day to Zagreb to meet a client there who wanted to buy a house. He asked me what the selling price was.

"Petdeset mejorih," I replied, my heart beating slightly faster as the prospect of an imminent sale.

This Purger had no idea what I was talking about. Eventually, I had to write down the figure of 50,000 euro so that he could understand. It turned out that I was speaking Jelsa dialect, a language I had become quite proficient in at the expense of learning proper Croatian over many beers on the pjaca. My word for 'thousand' was apparently understood only on Hvar, and the people of Brac would have looked at me equally as blankly, apparently. God knows what I would have ended up with I had ordered a thousand chisels in Hvar dialect.

Some of the Croatian dialects are totally impossible to understand, and there is even a case for questioning if parts of it can even be classified as language. Check out a common greeting in Dalmatia in the video above, the famous Dalmatian Grunt, as personified by Professor Frank John Dubokovich, Guardian of the Hvar Dialects.

These dialect differences cause real problems of understanding, and they often produce completely different sentences for the same meaning. In our previous series looking at Hvar dialects, check out the differences in these sample phrases of standard Croatian, The Professor's Hvar dialect, and the Dubrovnik dialect of a visiting tourist in the video above.

Interestingly, these dialect differences have been preserved with emigration in some cases. Here is a comment from a recent thread in a Facebook group on the Croatian language in the diaspora:

And that is the magic of spoken Croatian. Here in New Zealand we have people from many parts of Croatia. All brought with them a particular dialect. My family from Korcula had two dialects, one from Lumbarda, and the other Zrnovo. Listening to people from other villages in Korcula is a treasure!. I'm mesmerised by the dialect from Brac! My husband's family and friends from Drvenik were intrigued by my spoken dialect. Sadly, with education and media influences, the localised dialects will change. That is language for you!

Education, media influences and globalisation are all playing their roles in adding an additional level of comprehension issues to this most logical and phonetic language. As has recent history.

Serbian and Croatian languages have always been similar, but when the artificial country of former Yugoslavia was created, so too was an attempt to homogenise the langauges. The language of Serbo-Croat was born. Always a symbol of the hated communist regime, it did not take long for Croatians to revert back to some more traditional words, while a Tudjman era attempt to put linguistic distance between Croatian and Serbo-Croat generated many new words.

The Serbo-Croatian Oktober, for example, was replaced by one of my favourite words to describe a time of year - listopad, which literally means 'leaves falling', a perfect way to describe October. Meanwhile, at Tudjman HQ, 'aerodrom' was being replaced by 'zrackna luka' (literally 'air harbour/port'), 'helikopter' by 'zrakomlat.'

The biggest changes, however, are coming from globalisation and the influence of the Englsh language. This actually started in the diaspora many decades ago, and a lot of the 'Croatian' that is spoken there is actually Croglish - a mixture of Croatian grammar and English words. Check out some of the gems in the New Zealand Croatian language lesson above, for example.

But real change to the Croatian language has come from the Internet age and the dominance of the English language. I am amazed listening to my kids hanging out with their friends. The language of Croatian is often not Croatian, but English. While I would expect that between my own kids, for them to be communicating that way with their classmates is interesting. Good news for the next generation regarding language skills in the global market, less so perhaps for the future of the Croatian language.

A few days ago, I overheard a conversation which included the sentence:

"Ja sam hezitajtala." I hesitated. It was the first time that I had heard the such a use of the word hesitate in Croatian. And while it made things easier for me to understand as a foreigner, it made me wonder how the older generation of non-English speaking Croatians are managing to keep up with communications with the grandchildren. It was a topic I thought was worth looking into, so I took to Facebook to ask for other examples of new words which are creeping into the Croatian language. There was quite a response.

Croatian speakers, research help for an article please.

Foreign words are encroaching on the Croatian (and other) languages in ever greater numbers. Here is something on similar words and phrases to (itself under foreign influence) the verb 'šerati'

Lista riječi i fraza, sličnih 'šerati': lajkati, shareati, uploadati, sherati, tagirati.

This week a was listening to a younger generation conversation between Croats with Croatian as their mother tongue which inclued the sentence - Ona je hezitajtala (my spelling) - she hesitited.

My two questions

- What unusual/bizarre/extreme examples have you come across (with simple explanation if appropriate)?

- How does the older generation in your family who might not speak English deal with these linguistic changes? Do they understand, pick them up? Or is the language of the younger generation 'graded' according to the audience?

Interested in what you have. Leave comments below or send private message.

cheers Paul

Here are some of the gems which came back:

subskrajbaj se - subscribe

Ovo sam kopipejstala. - I copy pasted this

"sinati" (with long "i")- when you mark a WhatsApp message as seen. Two days ago, the weather reporter on N1 said that she will "monitorirati" the situation. As in monitoring. Also, "post" is usual when you want to describe something you posted on Facebook, instead of objava. When you come to a party, you can "minglati" (to mingle). It's endless. And no, the older non-speaking English have no idea what all this means. And no, youngsters don't adjust to the audience, they usually assume it's common knowledge.

Also, "bindžati", like binge watching

Najstrimanija (pjesma, h/t Laganini FM radio)

“Hendlati situaciju” - Handle the situation.

Sometime last year, I was driving, and listened Croatian Radio 2. They had some music top list, and at one point host (so, on public radio which should preserve national bla-bla-bla) said "Nju entri na našem čartu je..."

Skrinšot - screenshot

Just this week I saw an estate agent use a word 'za rentiranje', adapting to rent.

Čilati=chill out or relax

I'm actually making a list of words that come out of our politicians mouth, for which we have perfectly good ones - was planning to write a text using them, and then giving it to my grandmother and see if she'll understand anything....

Here are some...

Involvirati = Uključiti

Egzekucija = Izvršiti

Recentno = Nedavno

Evaluacija = Procjena

Deskripcija = Opis

Rola = Uloga

Respektirati = Cijeniti

Akceptirati = Prihvatiti

Genuino = (genuine, just lol)

Abandonirati = Napustiti

Signifikantno = Značajno

Oponenti = "Protivnici"

Akcesoar = Predmet/dodatak

Substituirati = Zamjeniti

Fragilno = Osjetljivo

Intencija = Namjera

Anticipirati = Predvidjeti

Egzaktno = Točno

and so on.... ![]()

My daughter started to use in conversation with friends words like: - sinala je - for seen /the message - livaj - to leave - đoinaj - to join - hejtati - to hate

Resetirati - to reset Isprintati - to print Softver - Software

The funniest word I came across was “a typo”, that is, apparently, “zatipak” in Croatian!

If it continues like this, Croatian will not only be the most logical and phonetic language, but also the easiest...

What Croatian language gems do you have? Drop us a line at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Subject Croatian Language.

Slavonia Students Spot 300 Spelling Mistakes In Names of Public Places

November 21, 2020 - How difficult is it to learn Croatian? Slavonia students from one high school learned it's really not so easy for people to correctly use their own language

How difficult is it to learn Croatian? Well, it's pretty difficult. Croatians know this best of all and will be reasonably impressed if you make any advances in trying to speak their language. A professor of linguistics from Zagreb University once told this writer that to be able to regard yourself as wholly proficient in the Croatian language, you would have to study it to no less than university level. Naturally, not every speaker of Croatian has done so.

Slavonia students from a high school in Slavonski Brod were recently tasked with looking for mistakes in the use of Croatian language in public places. So complex is the Croatian language, spelling and grammar mistakes are commonplace. The teacher assigning the task, Vesna Nosić from Matija Mesić high school, was no doubt confident her students would uncover some mistakes. However, the grand total of 300 spelling and grammar mistakes the Slavonia students found is possibly more than was bargained for. Particularly as those found were all assigned to public places. Matija Mesić high school in Slavonski Brod, where Slavonia students made their findings © Matija Mesić high school

Matija Mesić high school in Slavonski Brod, where Slavonia students made their findings © Matija Mesić high school

The misspelling or incorrect translation of food items on a restaurant or tavern menu is a regular cause of amusement in Croatia. But, the mistitling of public places - streets, squares, companies, monuments, traffic signs and even schools – is perhaps more surprising. These are places you walk past every day.

The Slavonia students were given the high bar of the official standards of Croatian language set by the Institute of Croatian Language and Linguistics. Their teacher, Vesna Nosić, has published their findings in the popular science journal Hrvatski jezik (Croatian language), which is published by the institute. Croatian language is something of a national obsession in Croatia, its acceptance as the official language very closely linked to the country's struggle for autonomy. For most of its history, the lands of modern-day Croatia were controlled by empires for whom Croatian was not their language. The use of foreign tongues has been imposed on the population of Croatia for centuries.

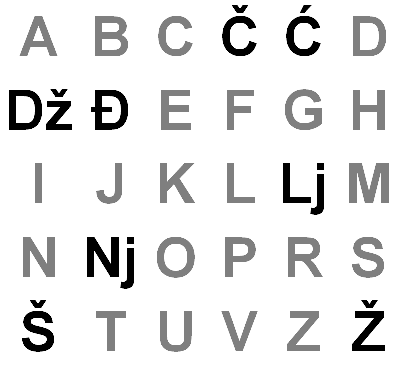

The most common mistakes made in the Croatian language are related to the incorrect use of the sounds ć and č, đ and dž. The letters here come from Gaj's Latin alphabet, devised by Croatian linguist Ljudevit Gaj in 1835. It is the Latin script used across the region in which to write the similar languages of Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, and Montenegrin (in Bosnia, Serbia and Montenegro, the Cyrillic alphabet is used as well as Gaj's Latin alphabet).

The contemporary version of Gaj's Latin alphabet (it originally contained Dj, which was replaced by đ. This alphabet ihe easiest part of learning Croatian - within 15 minutes, almost anyone can correctly pronounce all Croatian words by using this. In comparison to the Latin alphabet used by English speakers, the letters q,w,x,y are omitted. Instead, we get the additional č, ć, dž, đ, lj, nj, š and ž. Looks difficult? It isn't. Almost all of these sounds exist within the English language. Except for lj which, to English speakers, is torturously missing some kind of vowel © Albatalad

Mistakes between the ć and č or đ and dž sounds are understandable if you can pronounce Gaj's Latin alphabet. And anyone can. The easiest part of learning Croatian is Gaj's Latin alphabet – all of the sounds exist within the English language, all of the letters are always pronounced in exactly the same way (unlike English). The difference in sound between ć and č or đ and dž in spoken Croatian is difficult to perceive if you are not a native speaker (often, even if you are!)

Some of the mistakes found by the Slavonia students are perhaps more forgivable – the standard of Croatian their comparisons was made against is rigid. Thus, pekarna (bakery) instead of pekarnica, or dućan (shop) instead of trgovina were classed as mistakes, but are actually in everyday use on streets across Croatia.

Other mistakes found relate to grammar, spelling and the misuse of upper case or lower case lettering. For instance, Ulica Pavleka Miškina should be written Ulica Pavleka Miškine (the word ending changes to denote it is the street of Pavlek Miškina), Crkva Gospe od brze pomoći, should be crkva Gospe od Brze Pomoći; Muzej Brodskog Posavlja should be Muzej brodskoga Posavlja and Šetalište Braće Radić should be Šetalište braće Radića (denoting it is the promenade of the Radić brothers). Not sure which words should be in upper case or lower case in Croatian? Write everything in upper case - problem solved! © Slavonski Brod Tourist Board

Not sure which words should be in upper case or lower case in Croatian? Write everything in upper case - problem solved! © Slavonski Brod Tourist Board

Sitting to one side and watching how others do something, judging them, then informing them they are doing it incorrectly is not the most pleasant way to occupy your time. However, for the purposes of this study, this not-uncommon activity in Croatia is exactly what was asked of the Slavonia students. However, as noted in today's coverage of this story in Index, there is a great saying in Croatian that serves as a response to any unwanted judgments coming from those on the sides - “clean up the trash in front of your own doorstep before you discuss that which lies in front of your neighbour's”. And, that's exactly what the Slavonia students did – and found out that the name of their own school was spelled wrong.

Council of Europe Recommends Slovenia Recognise Croatian as Minority Language

ZAGREB, Sept 23, 2020 - The Council of Europe has again recommended that Slovenia recognise Croatian as a traditional minority language, the Council said on Wednesday.

The Committee of Ministers of the Council Europe reiterated its long-standing recommendation that Slovenian authorities recognise Croatian, German and Serbian, which are present in parts of Slovenia, as traditional minority languages.

In 1992, the Strasbourg-based organisation, which includes 47 member states, adopted the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages which aims to promote and protect those languages.

In a report based on the Charter, which entered into force in Slovenia in 2001, the Committee called on Slovenian authorities to enter into a dialogue with representatives of the three languages to strengthen their protection.

It is recommended to create educational models and to broadcast radio and television programmes in the minority languages, the press release said.

According to the 2002 census, 35,642 Croats lived in Slovenia, and Croatian was the native language of 54,079 citizens, the website of the Central State Office for Croats Abroad says.

Data on the nationality and the native language of the population was not collected for the 2011 census in Slovenia, it is added.

For the latest travel info, bookmark our main travel info article, which is updated daily.

Read the Croatian Travel Update in your language - now available in 24 languages

Croatian Language: Phrase it Properly

July 24, 2020 - Ever wondered what some famous Croatian phrases really mean? TCN contributor Ivor Kruljac breaks it down.

Croatian – that Russian sounding language, which isn't Russian. It is exotic and mysterious with only, give or take, around five million native speakers (plus Serbian and Bosnian speakers who can easily understand it). Apparently, it's a hard and challenging language to learn for non-Slavic native speakers, but with enough motivation and hard work, you can certainly learn more than 'dobar dan' (good day), 'hvala' (thank you) and 'doviđenja' (goodbye). Fascinating for its rich and diverse vocabulary (foul language in particular), one of the most interesting things about Croatian, as in any other language, is the phrases speakers use to paint a certain situation or express thoughts. Some are very similar or even the same as in English, but some are completely different ways to say the same thought.

Here are 12 phrases to enhance your enthusiasm to dig deeper into Croatian.

1.) Kad na vrbi rodi grožđe / When willow gives you grapes

The phrase 'When willow gives you grapes', which is the equivalent to ‘When hell freezes over’, is a suitable phrase to say that something will never happen. Although this phrase will maybe need some alteration once genetic engineering catches its full speed.

2.) Mačji kašalj / Cat's cough

The easiness of 'eating cake' has been replaced with what used to be a typical pet for farmers and today for those who don't prefer dogs - a cat. 'Cat's cough' means that something is really easy to do, so simple and harmless that you, in fact, don't even notice it, and it can also be used to describe something as irrelevant. Might sound a bit odd, but think about it, did you ever hear a cat cough?

3.) Pijan kao majka / Drunk as a mother

Translating to 'Drunk as a mother', this saying might suggest that Croatians are getting raised with a lot of family issues. However, the phrase comes from the past when hospitals were non-existent and home births were a regular practice. To ease the pain of childbirth, the mother would be provided with the only anesthetic people could find in their household: alcohol. Pending on the pain and the duration of labour, the new mother could be completely hammered by the time she gets to hold her baby in her arms. A bit less fun than for fiddlers who were enjoying alcohol in between their performance, but the end result is pretty much the same: a hard time recollecting last night.

4.) Pušiš kao turčin / You smoke like a Turk

Croatian memory didn't register that much smoke coming from the chimneys, but they do remember Turkish soldiers during the conquering spree of the Ottoman Empire. Noted as passionate smokers, even today people in Croatia would often say to you that you 'Smoke like a Turk', if you light your fifth cigarette before you even put sugar in your morning coffee.

5.) Mi o vuku, vuk na vrata / Speak of the wolf, wolf at the doors

Basically, 'Speak of the devil' only replace the king of hell with the wolf that is in front of your door just as you were talking about him. Scary not only because of his fatality for humans, the wolf was also hated among Croatian villagers for slaughtering sheep and other farm animals.

6.) Ispeci pa reci / Bake it and then say it

This is similar to 'Think before you speak' with some differences. With the translation being 'Bake it and then say it', it is a suitable response to everyone bragging about something while not having any proof they did it or are telling you how to do something even though they are not doing it.

7.) Trinaesto prase / 13th pig

The unlucky 'Thirteenth pig' is truly a clever deduction. To attribute someone who always got left behind, people compared him with a rare but very possible scenario when a pig gives birth to 13 piglets. With only 12 breasts for feeding, one always loses a meal.

8.) Točan kao švicarski sat / Precise as a Swiss watch

With its Rolex and Tag Heuer, Switzerland is a known symbol of quality and precision when it comes to wristwatches. Especially for Croatians. The older generations would often say to you that you are 'precise as a Swiss watch' when you arrive on time.

9.) U tom grmu leži zec / In this bush lies the rabbit

Not just an observation in hunting, 'in this bush lies the rabbit' is a common phrase to describe a situation when someone keeps a secret from you, or reveals his/her secret motives that explain something you couldn't quite put your finger on.

10.) Pamti pa vrati / Remember and return

'Remember and return' at first may sound a bit revengeful, and it is. But it can also mean to return a nice favour to someone. Basically, how you treat others, others will treat you. If someone was nice to you, remember that and be nice as well and if not, remember, so you don't make the same mistake twice.

11.) Bez muke nema nauke / Without suffering there is no knowledge

The Croatian version that's most similar to 'No pain, no gain' translates as 'Without suffering, there is no knowledge'. Guess it was easier for Croatians to learn from their own mistakes and not from others.

12.) Što se praviš Englezom? / Why are you pretending you are English?

In the past, Croatian territory was under the rule of the Romans, Austrians, Hungarians, Turks, French and even had close clashes with Tatars during Genghis Khan. The colonial force of the British empire does not go further in Croatia than Vis island, where in the 19th century, the Brits raised fortresses seeable today as you enter St. Juraj port. Despite that, English folks entered Croatian phrasing nevertheless. 'Why are you pretending you are English?' is a question for someone who had done something wrong but acted like he/she didn't do anything and didn't know what you are talking about. It can also be used to describe someone who acts more important than he/she really is, which might have been inspired by the aristocracy or even the Royal family itself. Good news for Britain, however, is that this phrase is less used among younger generations (which can also, let's be frank, be said for all of these phrases). Still, don't be surprised if you meet a cute and wisecracking Croatian group that might remember this and use it as a suitable joke for their English friends.

Public Call for Scholarships for Croatian Language Learning

As Glas Hrvatske writes on the 22nd of May, 2020, the Central State Office for Croats Outside the Republic of Croatia has announced a public call for scholarships for learning the Croatian language in the Republic of Croatia for the winter semester of the 2020/21 academic year.

The application for the aforementioned public call is to be submitted exclusively in electronic form using an e-application form by June the 17th, 2020.

The public call has been announced in order for would-be Croatian language learners to gain a better grasp of Croatian language, which is often referred to as a very difficult language to learn, get better acquainted with general Croatian culture and preserve the country's national identity outside of its borders, as well as to promote unity and cooperation and the return of Croats who have emigrated abroad, as well as their descendants.

Who exactly can apply? Members of the Croatian people, their spouses as well as friends of the Croatian people and Croatia who would like to nurture the Croatian identity and promote the Croatian cultural community, from the age of 18 onwards.

Those individuals must have completed at least their high school education and they must reside outside of Croatia. Those who hold residence in the Republic of Croatia may also apply, but their residence in Croatia must not have lasted longer than three years as of the day of the publication of this public call.

As stated, applications are being received only electronically, using the e-application form available here. To emphasise once again, the deadline for applications is June the 17th, 2020.

All details for this Croatian language course and more are listed on the link placed above, as are the attached instructions.

In case of the need for additional information, candidates can send their inquiries to the e-mail address: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Follow our lifestyle page for more.

How the Professor of Hvar Dialects Helped Preserve Croatian Culture & Tradition

May 7, 2020 - What a lovely email! How a fun YouTube series in the early days of TCN became a national phenomenon. It is all thanks to Professor Frank John Dubokovich, Guardian of the Hvar Dialects.

It started out as a joke, something to fill some content in the first month of my new portal, Total Hvar, way back in November 2011. It became such a cult hit that it soon hit national television, then British reality TV, and now - so I learned today 8.5 years later, a catalyst to preserve some of Croatia's dying culture forever.

My good friend from Jelsa, Frank John Dubokovich, was born in New Zealand but moved back to Jelsa at the age of 8, the Hvar town where his family are from. So he grew up bilingual, actually trilingual.

For Frankie spoke Jelsa dialect, which is a whole linguistic sub-species of its own.

An idea was born, to do a short video series of the differences between Jelsa dialect and standard Croatian, looking at different aspects of life - food, months of the year, articles of clothing - to demonstrate the differences. It started with the infamous Dalmatian Grunt, a video which is sadly no longer available online currently (but which I am trying to find), and which amassed almost 100,000 views on YouTube when I saw it last year.

As his flock grew, so did Frankie's authority, and he became the self-styled Professor Frank John Dubokovich, Guardian of the Hvar Dialects. Here is one of the original lessons, in which he investigates parts of the body in Hvar dialect, including a live demonstration of shaking his ass.

His fan base was truly international. The then assistant coach of the Australian football team jetted in from Sydney to meet with The Professor.

So impressed was Ante Milicic with The Professor that he even had his voice on his ring tone and wake up call.

It was only a matter of time before national television came calling.

HRT asked us to record a special lesson on dialect words for wine, which featured on their promo video 'Susur' in July, 2015. The Professor makes his entrance at 04:18 in the programme, above.

With such colossal talent, it was not long before the international talent scouts were in touch with TCN, and The Professor and his Hvar dialects were soon starring on British television reality shows.

How to get a bunch of chavs into Dalmatian grunting - genius!

So brilliant was The Professor that he even taught us how to speak Hvar dialect using only vowels on a guest appearance in Split.

And that is where I thought the story ended. A lot of fun on the way, and a lot of beautiful women falling at The Professor's feet, and the occasional Australian football coach waking up to the dulcet tones of The Professor each morning.

Until today.

Until the loveliest email of the year.

From Grgo.

Hey Paul! We haven't met in person but you've had a huge influence on me and what I have been doing last couple of years. It took me long time to finally contact you haha.

I want to thank you for the Hvar Dialect Lessons you started posting on YouTube 5-6 years ago. I was in shock, just like the rest of my friends from Zagreb and the area. It was super entertaining but also educational. It made me think (and the rest of us) how our authentic local heritage was fading away. General unawareness of this local universe we have across Croatia.

What happened next is I started recording the "Kajkavski lessons of Marija Bistrica" on YouTube with my local native speaker...in the end I spent most of my University along with my master project all about preserving and promoting local dialects and values in Croatia.

I graduated as a visual communications designer so I wrote and illustrated a tale in Kajkavski idiom, then posters and picture books for children...

Following that I started recording other people along the coast. Just last year spent two weeks on Dugi otok island recording the locals stories and their dialects. The project started connecting the locals across Croatia raising awareness. Schools and parents are calling me for the presentations... it's just crazy.

And all of it kind of started when I saw the first "Hvar Dialect Lesson" you posted. ?

Cheers from Zagreb!

Grgo

Love it. And so will Professor Frank John Dubokovich, Guardian of the Hvar Dialects, when he learns that we will be taking him all the way to Marija Bistrica to meet Grgo and do a Mother of All Dialects lesson when all this madness is over.

I can't wait, even though I probably won't understand a word.

Professor, we salute you. Your infamous grunt has inspired the preservation of more Croatian culture that the uhljebs in the ministry in an entire mandate.

I can't wait to hear how the grunt sounds in Marija Bistrica.

You can follow Grgo's excellent YouTube channel here.

Scholarships Offered for Online Learning of Croatian

ZAGREB, August 21, 2019 - The Central State Office for Croats Abroad has published a call for scholarships for online learning of Croatian in the coming school year.

The office will award 10 scholarships for attending the semester-long online courses of the Croatian language.

The grants refer to the online course called HiT-I organised by the University of Zagreb, the Croatian Heritage Foundation (HMI) and the University Computing Centre SRCE.

More information is available on https://matis.hr or on the Office's website.

Applications can be sent by ethnic Croats living abroad, and descendants of Croat expat communities as well as their spouses and foreigners interested in Croatian heritage and culture, provided that they are above 18 of age and have finished at least secondary school.

More diaspora news can be found in the dedicated section.