Zagreb Software Company Aids Scientists with Virus Spread Simulation

''If someone told me two years ago, when we were working on the BBC Pandemic app, that a pandemic would suddenly become a reality, I'd say there's no way, and well... it's happened,'' says Filip Ljubić, director of the Zagreb software company - Q.

As Filip Pavic/Novac writes on the 29th of March, 2020, not knowing that the world was awaiting the current coronavirus pandemic, this Zagreb software company launched a prophetic mobile app called BBC Pandemic, a virtual simulation of the spread of flu from person to person in 2018, in collaboration with the BBC and Cambridge University. The data it collected, the very first of its kind in the world, is being used today by scientists around the world to control the current coronavirus epidemic and to plan what's needed in regard to public health.

''The idea was to do the largest experiment in human history and to collect data that scientists hadn't been able to have before. It all started when we were contacted by the BBC, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of Spanish flu, to create an application for them that a user can download to their mobile device, through which we can monitor how the infection spreads from person to person, all of the ways it does so and at what speed it doesit. We then created the application,'' recounts Ljubić, who is one of the founders of Q, a Zagreb software company that has been developing web and software solutions since its inception back in 2013, and has an impressive list of clients, including Facebook, Volkswagen, The Times, Novartis, and more.

The application, he explains, is quite simple and not particularly technically demanding. Everything is anonymous, and the app only asks users for their gender and their age. Users download it to their mobile devices and thus become virtually ''infected''. As they perform their daily tasks, the app monitors their movements and their social contacts. The idea for each person is to collect the correct set of information about their activity, movement, professional status, travel habits and how often they come into contact with other people - 24 hours a day. During the day, they need to answer different questions within the app, such as how many people they were in contact with that day, how long they spent together, whether their train or bus on the way to work was full or empty, and how long that trip took.

''Scientists were looking for 10,000 people to download the app and participate in the experiment because that amount of people was necessary for a credible sample. In the end, almost 100,000 people downloaded the app, much to our surprise. Ten times what we'd hoped. The app has become a huge hit and has for some time been the number one medical app on the UK's Apple Store and on Google Play,'' says Ljubić.

This allowed scientists from the prestigious Cambridge University in the UK and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine to analyse the data for the first time in history and actually produce a credible "contagion map" of the so-called Heat Maps - graphical views of the spread of influenza viruses from one city to another and in towns and counties, and display the exact rate of its spread. The shocking revelations from the BBC app were later packed into the documentary Contagion, currently available on YouTube and Netflix.

Based on the movement of app users and their interactions, it can be seen that in the months since the outbreak, the number of people infected in the UK rose to more than 43 million people, nearly two-thirds of the entire population. The death toll in the first six months rises to nearly one million. One user who carries the virus, as they have shown, by going to a gym, cafe or shop, infects as many as nine people on average, and then they spread the infection exponentially even further. Mathematician Hannah Fry, who led the entire project, said it was "a unique project and a huge leap forward for science, and one day, these discoveries could save millions of lives."

''It's almost unbelievable that so soon after the launch of the application, a brand new epidemic, coronavirus, really happened and suddenly what the application simulated in theory began to happen in real life,'' says Ljubić.

''Last week, we were contacted again by the BBC and told us they were considering developing a new application that would track people with coronavirus symptoms in real time. We've only had a few conversations so far and we're still waiting for the green light,'' Ljubić revealed.

Make sure to follow our dedicated section for rolling information and updates in English on coronavirus in Croatia. Follow Made in Croatia for more on Croatian companies, innovation and more.

Croatian Tourism 2020 and Coronavirus: Let’s Postpone the Season

March 29, 2020 - How will Croatian Tourism 2020 look like? Paradox Hospitality CEO Zoran Pejovic on why we should postpone the season, and what that means.

Yes, there is a possibility that the pandemic will not be over before the height of the summer. Yes, there is a possibility that it might take another 12 months to tackle this crisis. However, in case that we start defrosting sometime in June and ramping up again in July and end up having good August and September, what we are doing to mitigate some of the effects of the lost preseason, of April, May and June? I am going to be kind here and assume that things are being done as we speak, but due to the lack of available information I am going to suggest the three most obvious measures that need to be taken at this point, other than direct financial relief to those who are directly affected by the crisis, especially to those that are legally forbidden to continue with their businesses:

Here are some of my thoughts that I hope Croatian National Tourist Board and Ministry of Tourism are already considering.

Start communicating to the World

I see no communication from Croatian tourism bodies towards the world. I see no visibility or messages of well-being towards the world. I have already written in the importance of staying visible and communicating as well as the type of messages we should be sending out to the world. Here is just one example, of us telling again the stories of Hvar Island literally being a health sanitarium, or the story of more than 600 wild medicinal, aromatic and honey plant species in Croatia, 120 of which are traditionally used in folk medicine, food, oils, spirits, and more. These are perfect stories to tell, they encompass both promotion and prevention emotions dealing in health aspects, well-being and safety simultaneously.

Here are also examples of how Portugal and South Africa have started communicating:

Negotiate with and incentivize airline companies to continue flying pass the current dates

If we take Split as an example, and If we look at the current flight schedules, most of the flights finishing throughout September, some even at the end of August. We need to have the continuous influx of flights throughout October and even November. October must make up for May and November must be our new April.

The airlines are hurting badly, and they are looking for government subsidies, but they are also trying to reschedule flights rather than return money for the tickets. So, perhaps it might be in their best interest to continue flying late into the year as well, much later than initially planned. We will have late start to the season but need to push well into the late fall if we are to salvage anything from 2020.

Shift the focus and start planning “Autumn 2020” project

Autumn can’t be about “sea and sun”, so this is a perfect opportunity to let go of some of the stereotypical views of Croatia as only a summer destination. If schools have managed to go online within a week, and some of the administrative apparatus managed to move closer to the 21. century within weeks, we can finally present Croatian tourism brand as a fusion of culture, history and gastronomy, all underscored with the strong wellness message. All messaging has to reflect this new narrative.

Short term speaking focus back almost entirely towards the most resilient markets, and in this case that means, the wealthiest ones so the Nordics, Switzerland, Benelux countries and Germany. Advertising budgets need to be channeled from Asia and United States to the European emitting markets.

This also means that the ferry lines need to keep going longer into the fall, national parks must stay open longer and many other concessions and trade-offs have to be undertake, some of which might even include free highway tolls for those that are driving to Croatia.

If we don’t salvage something of 2020, assuming the pandemic allows, 2021 will not be a year of recovery, but a year of complete mess and disarray.

You can read more on this subject of post-coronavirus travel from Zoran here:

Travel Industry: Keep Communicating and Visibility

Build Scenarios! Be Present! Take Time to Think!

Post-Coronavirus Travel and Tourism: Some Predictions

You can connect with Zoran Pejovic via LinkedIn.

Did I Just Recover From The Coronavirus?

March 29, 2020 — The chills hit shortly after lunch on March 9. I curled into a fetal position on the couch and threw a blanket over my shivering body.

It was the early stages of life during a pandemic. The deadly, still-mysterious and oft-dismissed coronavirus had lifted the handbrake on the global economy and was about to transform many hospitals into dens of tragedy.

I stabbed a thermometer under my tongue and checked the news: Italy was fumbling its early response. Fresh cases were trickling into Croatia via returnees.

The World Health Organization in a press conference said, “Now that the virus has a foothold in so many countries, the threat of a pandemic has become very real. But it would be the first pandemic in history that could be controlled.”

My temperature was 37.6℃ (99.7℉) — ignorable in almost all circumstances.

Two days later, the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic. I reached for my thermometer.

A Smorgasbord of Maladies

I developed a cadre of symptoms over the next 24 hours — some obvious, others I ignored then later added to the tally.

First came chills and body temperature fluctuations of up to 37.8℃ (or 100℉). Then diarrhea, dizziness, nausea, and an intense one-day headache, debilitating fatigue which felt like gravity doubled its force on my body.

I didn’t cough.

A doctor assured me over the phone it was a stomach bug. I agreed. She suggested I stay hydrated and call back in three days if the symptoms didn’t clear up.

While she spoke, I Googled “fever diarrhea + coronavirus”, aware of the perils of patient self-diagnosis and the “worried well.”

The less-obvious symptoms arrived one-by-one over the first 48 hours. All food became tasteless. I couldn’t smell anything. My nasal passages, sinuses, and throat felt drier than gravel.

The fatigue and lethargy became all-consuming. A trip from the restroom to the couch felt torturous. Sustained movement lasting more than 90 seconds required hours of nap time.

It rendered me useless to my wife and our three dogs, who seemed to roll their eyes at me.

I’m hypersensitive to all maladies. An odd mole has me planning my funeral. An unexpected cough has me Googling “early lung cancer symptoms” (which runs in the family).

I’m arguably not mentally equipped for an undiagnosed mild fever in the middle of a global pandemic.

Croatia had 13 confirmed coronavirus cases by the end of the day.

The Limited Testing Commandment

In Croatia and many other countries, coronavirus was — and in some places still is — treated like a game of tag: You can’t be “It” unless an already-infected person or surface touches you.

Vili Beroš, the steadfast Croatian health minister who has become an unexpected hero, has repeatedly downplayed the efficacy of widespread testing. Isolation, tracking, treatment and social distancing are key, he says.

“If we continue to fight in this way against the epidemic, we will see fewer harmful consequences,” he said at the Civil Protection Directorate's Sunday’s press conference. “Responsible behavior is the key to success.”

The assertion runs contrary to the practices of larger and richer countries like Germany and South Korea. They credit their outcomes and low death rates to widely-available tests, social distancing and high-quality healthcare systems. Croatia arguably has only one of those three options, hence Beroš’s pleas for cooperation.

The novel coronavirus needs to stop encountering novel people.

Being a low-level recluse on a nearly-abandoned island prevents these sorts of collisions. So who would even infect me?

I could only think of a dinner four days before my first symptoms with a group of friends visiting from Zagreb. But none had visible signs of COVID-19.

Yet my fervent Googling of my symptoms pointed to anecdotal evidence that my supposed stomach bug might be something else. Researchers in China documented cases of COVID-19 with gastrointestinal symptoms, without the telltale cough.

The Mrs. and I were supposed to head home to a bucolic little island off the Dalmatian coast with an overwhelmingly geriatric population: a deep pool of diabetics, pulmonary patients, walking cardiac problems, and a slew of alcohol and tobacco-related issues.

If I was carrying some unorthodox version of COVID-19, I’d arrive on that island like a gatling gun of death, single-handedly turning it into a ghost town.

I needed to be sure I didn’t have the virus. I didn’t want to kill my neighbors. After four days of bland food, mud butt, and lethargy, I called my doctor again.

The nurse answered, and I blurted out, “It’s me. Orovic, Joseph. I need to know I don’t have the coronavirus.”

A pause. “Are you still having stomach problems?”

“Yes, and I read that might be a symptom of…” I stammered. “Look, I’m about to go to an island with a bunch of old people who will die if they get coronavirus. How can I get tested?”

***

The on-call epidemiologist picked up the phone after two tries.

“Hi, I need to know I don’t have coronavirus.”

She sniffled. “What are your symptoms?”

I rattled off my condition. She paused.

“And where did you come from? Italy? China?”

“Iž, an island off the coast, but I’m in Zadar now,” I said. “That’s why I’m calling. I don’t want to go back and infect the people there.”

“Did you spend time with anyone who came from those or other countries? Austria maybe?”

“I had dinner with some guys from Zagreb,” I said, feeling stupid as the words slipped past my lips.

The epidemiologist giggled.

“You can’t get infected unless you came from Italy or China or one of those countries,” she said with authority.

“So there’s no community transmission in Croatia?” I asked, with tales of South Korea’s “Patient 31” echoing in my head.

“No, no community transmission,” she replied. “Relax, whatever you have will go away.”

The “no community transmission” edict was central Croatia’s early response to the coronavirus. All confirmed cases were Croats returning from western Europe or were closely related to the confirmed patients.

The notion that the virus was already within the population and spreading was gently dismissed in earlier press conferences.

My doctor sent me in for blood work and samples to rule out a bacterial infection. All came back negative. I was a sick man without a diagnosis in the middle of a pandemic.

My flustered wife told me ride out the rest of my mystery ailment on the island.

Instead, I called a doctor.

“Can I go to an island if I’m not sure I don’t have the coronavirus?” I asked while the doctor read over my file.

“Did you say ‘island?’ Go! Now!” he said, suggesting 14 days of voluntary isolation and to call if my symptoms worsen. I obliged.

By this point, Croatia had 39 confirmed coronavirus patients.

Mysterious changes on a little island

The island spurred an odd fluctuation in my symptoms.

The stomach issues waned after the first week. My body temperature still rose and dipped at odd moments. My complete disinterest in food and constant lethargy caused close to six kilos (13 lbs) of weight loss.

I finally noticed our dog’s pillow smells like a burning garbage dump — so my nose was working again.

No cough.

Then on the seventh night, a tingling sensation in my chest woke me. It was as if someone rubbed toothpaste on my lungs.

I asked the same question almost every Dalmatian islander recites during a medical quagmire: What are the odds I will die before the next ferry to the mainland?

This is our reality. Medical helicopters remain an oft-promised but never-delivered pipe dream. Emergency boats sometimes take over an hour to arrive, with the trip back to the hospital lasting just as long.

The odds of surviving a life-threatening emergency like internal bleeding, heart attack or stroke are demonstrably lower here. What about chest pain during a pandemic?

I gambled on sleeping it off. Had I been on the mainland, I might have called an ambulance.

The pain subsided by the next morning and I dismissed it as a panic attack. But the temperature and lethargy lingered. Slowly, the lulls between my body temperature spikes and fatigue grew. I felt healthier more often and slept less.

On St. Joseph’s Day, ten days after my first symptoms, I declared myself “better.”

Croatia then had 105 confirmed coronavirus cases, with five patients fully recovered.

An Unwelcome Return To Abnormal

The morning of Zagreb’s earthquake, I tapped out a news brief on my phone, sent it to an editor in London then felt heat sizzle up from my chest to my jaw.

The thermometer read 37.4℃ (99.3℉) and rising. The ensuing, unexpected four-hour nap on the couch confirmed I celebrated too soon.

I was 13 days into a demoralizing stupor, my energy whittled down to slow-churning despondency. A radioactive sensation emanated from my torso. Life in the house changed.

My wife and I often took awkward, broad steps around each other like opposing gunslingers at a saloon. We avoided contact even though, ostensibly, I only had “some virus.” I wiped down faucet handles and hit light switches with my sleeve. She didn’t seem to notice.

Outside my home, life shrunk to a miniature version of itself. The government limited public gatherings to groups of five. Only private enterprises selling food, drugs, diapers, cigarettes, newspapers or gasoline remained open.

The ceremonial stop at the cafe between bursts of toil — the social lifeblood of this region — became verboten. People were told to remain in their neighborhood no matter how much the ground shook.

In Italy, nearly 1,000 people were dying every day. I watched in quiet distress as my hometown Queens, New York became the pulsating center of the United States’ coronavirus battle.

All this happened as I laid on a couch, pathetically knocked out by a middling fever and fatigue caused by a mystery virus.

The day of Zagreb’s earthquake ended with 254 confirmed COVID-19 cases in Croatia.

Two weeks after my first fever, I began recognizing my unorthodox symptoms in new reports.

New evidence suggested anosmia — a loss of sense of smell — seemed to be a symptom. Fatigue also made the list. Then finally, sitting down on the toilet more often than usual, without a dry cough, became an anecdotal sign of some alternate manifestation of the virus.

First-hand accounts from confirmed COVID-19 patients offered a picture of life with a “mild” version of the virus. Coughing and fever were the telltale signs of infection for most. But some bypassed that phase altogether and suffered other ailments.

One friend asked me a brutal question: “How many more people like you are out there?”

I couldn’t say.

I checked the newest stats. There were 495 confirmed COVID-19 infections in Croatia, and two deaths.

I’m now 20 days removed from that first shivering on the couch. I’ve had four full days of symptomless life. For all intents and purposes, I’m back to normal. I still don't know if I had COVID-19.

This island appears to be infection-free as well. We’re hoping it stays that way.

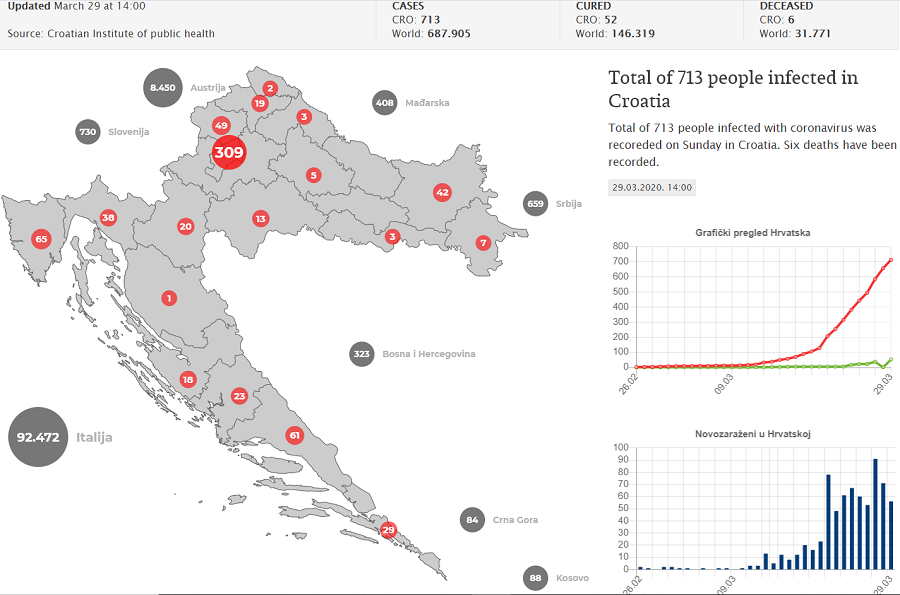

Croatia now has 713 confirmed cases of coronavirus of 5,900 tested, with six deaths, 26 patients on respirators and 52 recovered.

Wash your hands and stay at home.

Igor Rudan: Cascade of Causes That Led to COVID-19 Tragedy in Italy and Other EU Countries

March the 29th, 2020 - Professor Igor Rudan is the Director of the Centre for Global Health and the WHO Collaborating Centre at the University of Edinburgh, UK; he is Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Global Health; a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and one of the most highly cited scientists in the world; he has published more than 500 research papers, wrote 6 books and 3 popular science best-sellers, developed a documentary series "Survival: The Story of Global Health" and won numerous awards for his research and science communication.

The perception of the COVID-19 pandemic in my homeland Croatia has been based on two main sources of information over the past three weeks. On the one hand, our Civil Protection Headquarters, as well as all of the experts and scientists to whom media space has been provided, called for caution, but without any panic. They emphasised that this was not a cataclysm, but an epidemic involving a serious respiratory infectious disease. The cause of this disease is the new coronavirus, for which we don’t have a vaccine. Therefore, it can be expected that the disease will be very dangerous for the elderly and to those who are already ill. So, it was an unknown danger worthy of caution, but our epidemiologists remained calm. They knew that they would be able to estimate the epidemic's development using figures, and then control the situation with anti-epidemic measures, and through several lines of defense.

On the other hand, we also followed the events in Italy. From there, day after day, apocalyptic news came, with incredibly large numbers of infected and dead people. Daily reports from Italy seemed completely incompatible with what the experts and scientists in Croatia were saying. Some have concluded that a scenario similar to that in Italy, if not worse, is inevitable for Croatia. The population was in a very confusing situation.

In this text, I will try to penetrate the very core of the "infodemia" that has been present in the media across many European countries, as well as on social networks, over the past three weeks. I will explain how that disturbing situation arose and offer a scientific explanation for it. This seems important to me at this point, because the Italian tragedy with the COVID-19 epidemic has, unfortunately, hindered the credible and scientifically based communication of the epidemiological profession to the population of Croatia.

In my article "20 Key Questions and Answers on Coronavirus" posted on the 9th of March, 2020 on Index.hr, in answer to question number 18, "With the effectiveness of quarantine in China, can we draw some lessons from this pandemic?", I stated:

"If the virus continues to spread throughout 2020, it will demonstrate in a very cruel way how well the public health systems of individual countries are functioning… These will be very important lessons in preparation for a future pandemic, which could be even more dangerous.’’

We’re now slowly entering a phase where many countries have been exposed to the pandemic for long enough. Thanks to this, we can make some first estimates of their results. From these days up until the end of the pandemic, we’ll see that COVID-19 will divide the world into countries that have relied on epidemiology and followed the maths and the logic of the epidemic, as well as those in which this isn’t the case, and many sadly, probably quite unnecessarily - will suffer.

An epidemic is a serious threat to entire nations, during which residents' interest in other topics may vanish quite rapidly. We could see that happening quite clearly in the past several weeks. The task of epidemiologists is to constantly have tables in front of them with a large number of epidemic parameters, reliable field figures and formulas to monitor the epidemic's development, and to know the ‘’laws’’ of epidemics, in order to organise the implementation of anti-epidemic measures in a timely manner and thus protect the population.

Now, let's look at the countries that we can already point out as being successful in their response to this new challenge. First and foremost, there’s China. It has completely suppressed the huge epidemic in Wuhan, which spread to all thirty of its provinces. In doing so, it relied on the advice of its epidemiologic legend, 83-year-old Zhong Nanshan. Twenty years ago, Nanshan gained authority by suppressing SARS. Although surprised by the epidemic, they managed to suppress COVID-19 throughout China through expert and determined measures. They did so over just seven weeks, with the death toll eventually coming to a halt at less than 5,000. By comparison, it would be as if the number of deaths in Croatia as a result of this epidemic was kept at around 14 in total.

Furthermore, if at some point you find yourself caught up in the uncertainty surrounding the danger of COVID-19, you will easily be able to find out the truth if you look at the state of things in Singapore. Despite intensive exchanges of people and goods with China since the outbreak of the epidemic, Singapore has a total of 732 infected people as I am writing this article, with two dead and 17 more in intensive care. This city-state has the ambition to be the best in the world in all measurable parameters. From this, it must be concluded that the developments in Singapore are a likely reflection of the real danger of COVID-19. However, this is true of countries that base their regulation on knowledge, technology, good organisation and general responsibility. The situation in Singapore, therefore, is an indicator of the effects of the virus on the population, to the extent that it is truly unavoidable.

Any deviation towards something worse than the Singaporean results will be less and less of a consequence of the danger of the virus itself, and increasingly attributable to human omissions. In doing so, human errors that can lead to the unnecessary spread of the infection are: (1) the epidemiologists' omission to properly understand the epidemic parameters; (2) decision-makers' reluctance to make decisions based on the recommendations of epidemiologists; and (3) the irresponsible behaviour of the population in complying with government instructions.

To confirm the statements about Singapore, let's look at the current situation in other countries that rely on knowledge and expertise and have good organisation. They were also the most common destinations for the spread of the epidemic from China in the first wave: Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar. There were only 519 infected people in Hong Kong at the time of writing this article, with 4 deaths and 5 more people in a serious condition; in Japan 1,499 were infected, 49 were dead and 56 were in a serious condition; in South Korea, which had a severe epidemic behind its first line of defense, 9,478 were infected, 144 died and 59 were seriously ill; in the United Arab Emirates, 405 were infected, 2 died and 2 were seriously ill; and in Qatar, 562 were infected, 6 were seriously ill, and still no one had died from COVID-19.

Fortunately, Croatia is now up there with all of these countries, with 657 infected, 5 dead and 14 more seriously ill. As you can see pretty clearly from all of these figures, in countries that rely on knowledge and the profession and properly applied anti-epidemic measures, COVID-19 is a disease that should not endanger more than 1 percent of all infected people. This conclusion can be reached by considering that the information on the "https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus" page is based on positive tests, and not on everyone who is actually infected.

What, then, is happening in Italy, as well as in Spain, but to a good extent also in France, Switzerland, Belgium, Austria, Denmark and Portugal? I did not include Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States in this group of countries for now. This is because at least for some time during the epidemic, they have clung to the idea of intentionally letting the epidemic develop and infect at least part of the population, so I will refer to their strategies and their results in one of my following texts.

Given all of the previous examples of a successful epidemiological response, and what is now practically the coexistence of people with the new coronavirus in Asia's most developed countries, how is it possible for Italy to have nearly 85,000 infected people and over 9,000 deaths at the time of this article? How is it possible that Spain has 72,000 infected people and more than 5,600 deaths, and France has almost 33,000 infected people and 2,000 deaths? Or that even Switzerland, which everyone would expect to see among the most successful countries in any of these world rankings, could already have 13,250 infected people and 240 deaths, with 203 more critically ill people? The causes of all of this are, however, becoming increasingly clear to science.

First of all, there was probably a premature relaxation around the real danger of COVID-19 in Europe. The epidemic development by the end of February was already quite similar to the one seen previously with SARS and MERS. Even then, the primary focal point was suppressed, and in more than 25 countries, the virus was then stopped at the front lines of defense. By the end of February 2020, it was already clear in the case of COVID-19 that it would be successfully suppressed in its primary focal point - Wuhan. It was also already stopped at the front lines of defense in another thirty Chinese provinces and surrounding countries in Asia. Then, on February the 28th, the first estimates of death rates were published, saying that it was a disease with a death rate significantly lower than that of SARS and MERS. At that time, it was reasonable to expect that the epidemic could soon be

stopped. As a result, the World Health Organisation delayed the declaration of a pandemic until March the 11th, and the world stock markets increased by about 10 percent from February the 27th to March the 3rd. But for any unknown virus, premature relaxation is very dangerous, as will be shown later with COVID-19.

Secondly, several investigative journalists reported that it may be possible that the phenomenon of the mass immigration of Chinese workers to northern Italy may have contributed to the early introduction and spread of the virus in Europe. Tens of thousands of Chinese migrants work in the Italian textile industry, producing fashion items, leather bags and shoes with the brand "Made in Italy". Partly as a result of this development, direct flights between Wuhan and Italy were introduced. Some estimates say that Italy has allowed up to 100,000 Chinese workers, initially from Wenzhou, but later also likely from Wuhan and other cities neighbouring Shanghai, to work in those factories. Some of them may have been there illegally and worked in conditions where they were cramped together, which would help the virus to spread easily. Reporter D. T. Max wrote about this phenomenon in the New Yorker magazine back in April 2018. After their return from the Chinese New Year celebrations in mid-February, the Italian authorities rigorously checked these workers on their "first line of defense" at the airports. But rumours began spreading that some had begun to enter Italy but were bypassing Italian airports. Instead, they were going through other airports in the EU where controls weren’t as tight. So, the COVID-19 epidemic was likely triggered behind the back of the Italian "first line of defense", which remained unrecognised in the first few weeks.

Third, many infected people from northern Italy spent their weekends at European ski resorts. Although we don’t know if the arrival of the warmer weather will stop the transmission of coronavirus, what we can assume is that the cold helped it to spread. That is why European ski resorts became real nurseries of coronavirus in late February and in early March. In this way, more infected people emerged behind the front lines of defense in France, Switzerland, Belgium, Austria, Denmark, Spain and Portugal. Their first lines of epidemiological defense focused on air transport from Asia, not on their own skiing ‘’returnees’’, where indeed no one would expect a large number of Chinese people from Wuhan to be.

Fourth, although Spain may not have had as many skiers as other European countries in this cluster, the virus may have been introduced to them through a "biological bomb". On February 19th, a Champions League football match was held between Atalanta and Valencia. Atalanta is a team from a small city of Bergamo, Italy, which has 120,000 inhabitants. This was possibly the biggest game in Atalanta's history, as it progressed through group stages to the last 16 in the European Champions League. The local stadium was not large enough for everyone who wanted to attend the game, so it was moved to a large San Siro stadium in Milan.

The official attendance was 45,792, meaning that a third of Bergamo’s population, with around 30 busses, travelled from Bergamo to Milan and then wandered the streets of Milan before the game. Unfortunately for Spain, nearly 2,500 Valencia fans also traveled to the match. As Atalanta scored four goals, a third of Bergamo's population was hugging and kissing in the cold weather four times and spent the day closely together. This is likely why it became the worst-hit region of Italy by some distance. Unfortunately, at least a third of the Valencia football squad also got infected with a virus and later played Alaves in the Spanish league, where more players of that team got infected. This football game has certainly contributed to the virus making its way to Spain.

Fifth, it’s very important for the early development of the epidemiological situation in each country to look at which subset of the population the virus has spread among. Northern Italy has a very large number of very old people. In the early stages of the epidemic, the virus began to spread in hospitals and retirement homes. They didn’t have nearly enough capacities to assist in the severe cases. Among already sick, elderly and immunocompromised people, the virus spread more easily and faster and had a significantly higher death rate. In some other countries, such as Germany, most of the patients in the early stages were between the ages of 20 and 50, and were returning from skiing trips or were business people. Therefore, such countries have a significantly lower death rate among those first infected.

Sixth, and what the most important thing needed to understand the current situation in Italy is, must have been either the omission of Italian epidemiologists to monitor the mathematical parameters of the epidemic, or perhaps their lack of clear communication of the dangers to those in power in northern Italy, or the indecisiveness of those in power to adopt isolation measures for the population. It is difficult at this time to know which of these three causes is the most important, and a combination of all of them is entirely possible. However, I will explain the nature of the omission, as it largely explains the terrible figures on infections and deaths that are being reported from Italy on a daily basis.

To understand the story of this tragedy in Italy, we must first return to Wuhan. When the epidemic broke out, the Chinese first had to isolate the virus. Then, they needed to read its genetic code and develop a diagnostic test. It all took time, as the epidemic spread rapidly throughout the city. When they began testing for coronavirus, between January the 18th and the 20th, they had double-digit numbers of infected people. Those numbers apparently stagnated, so the epidemiologists didn't know what that might mean. But on the 21st of January, the number of newly infected people jumped to more than 100. On the 22nd of January, it jumped to more than 200. This was a clear signal to Chinese epidemiologists that an exponential increase in the number of infected people was occurring. At that time, they had nothing further to wait for, or to think about. If the virus breaks through the first line of defense - and the Chinese didn’t even have any, since the epidemic started there - then a quarantine measure needs to be triggered. This prevents the virus from spreading further and creating a large number of infected people through exponential growth.

After such a sudden declaration of quarantine in Wuhan, the huge epidemic wave of the Chinese had actually just begun to show. Everyone who was already infected began to develop the disease in the next few days. The maximum daily number of new infected cases was reached on the 5th of February. On that day alone, as many as 3,750 new patients were registered in Wuhan. Remember, this means that the jump from about 125 to about 250 registered newly infected people signals to epidemiologists that we should expect an epidemic surge in 14 days, with as many as 3,750 newly infected people in one single day.

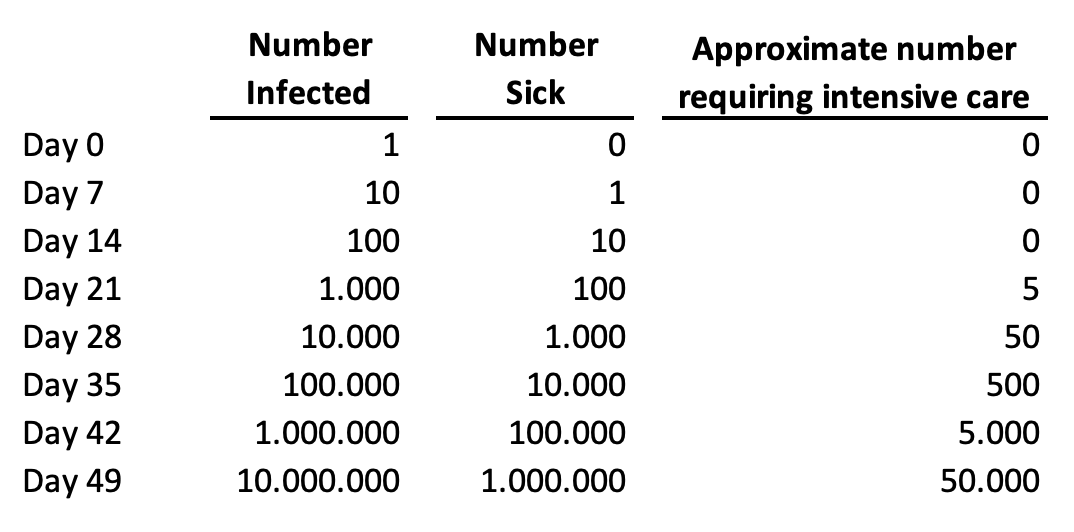

Let's now explain this "time delay" between people getting infected with the virus and the health system being able to detect all those infected people based on their symptoms. The new coronavirus kills primarily because it spreads incredibly quickly among humans. As a result, it creates a gigantic number of infected and sick people in a very short time period. Among those who are sick, about 5 percent will require hospital care. If all of them could receive optimal care, we'd be able to save nearly everyone. But if they all get very sick at the same time, we can't offer them adequate care and nearly all of the critical cases will die. This is the primary way in which this virus kills so many people. It is illustrated in a very simple way in this table, based on day-to-day growth in a number of cases by 26 percent, which was a very realistic scenario for most EU countries:

TABLE ONE: The dynamics of the epidemics of COVID-19 in any given country, based on a realistic scenario of about 26 percent of day-to-day growth of the number of cases:

With this in mind, let's now look at the Italian reaction to their own epidemic. In the early stages of infection spreading in a country, one or two infected persons are usually detected daily. Personally, I advised the Croatian authorities and public to start seriously thinking about social exclusion measures when they noticed the first notable shift from the first 10 confirmed infections towards the first 20 infected people.

On March the 12th, I posted a Facebook status entitled "Contrast is the mother of clarity", which was viewed and shared by many thousands of my fellow Croatians who have been following my popular science series on the pandemic - "The Quarantine of Wuhan". This status has also been shared by many online and printed newspapers and media, including radio stations. In that status, I suggested that Croatia should consider a large quarantine because we had already jumped from 14 to 19 infected people the day before, but to also weigh this against the economic implications and their expected effect on health. The very next day, a decision was made to close the schools.

That meant that, up to that point, Croatia completed two of the most important tasks in this pandemic. The first task was to hold its first line of defense. This was being achieved through the identification of infected cases imported from other countries and their isolation, and that of all of their contacts. Croatia completed this first task better than the other EU countries did, based on an average percentage increase of cases between the 3rd of March and the 17th of March. Then, from March the 13th, Croatia also began to introduce social exclusion measures at the right time, thus successfully carrying out the second key task in controlling its own epidemic. Many credits go to its epidemiologists who work at the Croatian Institute for Public Health.

But, what went wrong with these two measures in Italy? On the 21st of February, their number of confirmed infected cases jumped from 3 to 20. As Italy is a more populous country than Croatia, it might have still been too hasty to send all of Lombardy into quarantine based on this. But on the 22nd of February, the jump was from 20 to 62 cases, and they already needed to think very seriously about it. A couple of days later, on the 24th of February, they reached a situation very similar to that in Wuhan as the number of confirmed infections jumped from 155 to 229. This was particularly worrying because they didn't seem to be performing many tests proactively at that time, either.

That "jump" from 155 to 229, in combination with the Wuhan experience, should have suggested that they would have at least 50,000 infected people under the predicted curve of the epidemic wave and they were just seeing its early beginning. And that many infected people would mean that about 2,500 affected would require intensive care units. At the time, Lombardy had only about 500 such units in government/state facilities and another 150 in private healthcare facilities. As early as 24th of February it was clear that there would be many deaths in Lombardy weeks later. With epidemics, everything goes awry because the infected get sick a week later, and some of the patients then die ten to twenty days later, so the time delay is always an important factor that needs to be taken into account.

However, even then, the Italians didn’t declare a quarantine. They didn’t do so on the 29th of February, either, when the total number of infected people rose from 888 to 1128. Those figures implied that in mere days they would be having about 15,000 newly infected people each day. Moreover, they didn’t declare quarantine on the 4th of March, either, when the number of infected people exceeded 3,000, and when the world stock exchanges started to fall again. It had then become clear to most epidemiologists who have been advising global investors that an unexpected and major tragedy was about to unravel in Italy and this was now inevitable. At that point, Italy already had at least 30,000 infected people spreading the infection. The quarantine was declared for Lombardy on the 8th of March. The day before, the number of cases had already risen, and exponentially so, to as many as 5,883.

To appreciate the problem with epidemic spread in the population behind the first line of defense, this is similar to borrowing 1,000 Euros from someone on the 29th of February with an interest rate of 26% each day, meaning an interest rate of 26% on top of that the next day, and so on. Furthermore, there didn’t seem to be enough clear and decisive communication with the public. The news of the quarantine for Lombardy was, in fact, leaked to the media before it was officially announced. This led to a quick ‘’escape’’ of many students to the south of the country, to their homes, carrying the contagion with them. As a result, a day later all of Italy had to be quarantined.

In an already difficult situation, where every new day of delay meant another thousand or more people dying, as we can all notice these days, there were numerous media reports warning that the population may not have taken those measures as seriously as the Chinese when they introduced orders to their population in Wuhan. Any indiscipline under such grave circumstances could have allowed the virus to take yet another step quite easily. With each new step, another 26% of interest was added to everything before that, and then 26% on everything on everything before that again. That is the power of exponential growth, characteristic of free spread of the virus in the population.

Many Italians and then Spaniards, as well as residents of several other wealthy countries in Europe, had their lives cut short by their lack of recognition of the dangers of exponential function during the spread of the epidemic. Delaying quarantine for a week made the epidemic ten times worse than it should have been. Delaying it for two weeks made it a hundred times worse. And after two weeks of it being finally proclaimed, all those who may have not taken the orders seriously enough would have made the epidemic several hundred times worse. This means that, in Italy, and possibly in Spain, too, we are now observing the COVID-19 epidemic that is more than a hundred times worse than it should have been in a country that was much better prepared for the response, such as Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong or the United Arab Emirates.

To appreciate what is happening in Italy, it is enough to think of this sentence alone: at least 100 times fewer people would die each day if quarantine had been declared 2 weeks earlier and had the population stuck to the recommendations. During those fourteen days between 23rd of February and 7th of March, they unnecessarily allowed the virus to spread freely and infect a huge number of people - maybe even up to a million, or perhaps more, it is very difficult to know at this point. This would mean tens of thousands of people in need of intensive care, with about ten times fewer units available nationwide. About half of those who fall seriously ill will not survive without necessary support. At this point, whenever we hear that 1,000 people died in Italy in one day, we should know that the casualties would only add up to 10 had the quarantine been declared just a couple of weeks earlier. I appreciate that it seems implausible that the delay of a political decision like the introduction of quarantine by just two weeks may mean the difference between 100 deaths and 10,000 deaths in the 21st century, but I’m afraid that is unfortunately the reality of the exponential growth of the number of infected during an epidemic.

What does this mean for the public in countries like Croatia, who were confused and in awe of the events in Italy? They should know that they didn’t observe what the COVID-19 epidemic should actually look like in a country where the epidemiological service and its communication with those in power works well, as it does in Singapore, Taiwan or South Korea. In Italy, we have unfortunately noticed the consequence of an omission of epidemiologists and those in power to protect the people from the epidemic. Such a development was not predictable at all. The biggest surprise of this pandemic to date is undoubtedly the lack of response by the Italian authorities to the apparent spread of the pandemic at an exponential rate for two weeks, leading to a very large numbers of infected people in a very short time. But, it is even more surprising that, although the Italian example exposed the lack of capacity of their healthcare system to provide care to all those in need, a similar scenario is now happening in several other European countries in this group, that I initially singled out.

How and why could something like this happen in Italy and then in other countries in the European Union (EU)? I will try to offer at least some hypotheses. First, EU countries have been living in prosperity for decades, focused mainly on their economies. Aside from the economic questions, they haven’t had any challenges that they’ve had to answer to swiftly and decisively, that would measure up to this one. Back in the 1960s, vaccines were introduced against most major infectious diseases, especially childhood ones. Malaria is no longer present in Europe and tuberculosis has been treated similarly for decades. The challenge of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s is now being successfully controlled with antiretroviral drugs. Liver inflammation is treated mainly by clinicians. The impact of influenza is controlled through vaccination while rare zoonoses are resolved with immunoprophylaxis. Even sexually transmitted infectious diseases (STDs) are no longer as significant since the vaccine for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) was licensed.

The last real epidemic that concerned Europe was the Hong Kong flu, which occurred back in 1968 and 1969. The broad field of biomedicine offers such a wide range of exciting career paths to all those students who study it these days, but the epidemiology of infectious diseases is certainly not one of them, at least it has not been in Europe for a very long time. It has probably begun to seem as an archaic medical profession to the large majority of students and young medical doctors. It seemed to belong to the past for the European continent, which made it one of the least attractive things to specialize in. Even the rare epidemiologists who specialized in infectious diseases have begun retraining for chronic non-communicable diseases, due to the aging of Europe's population, which is particularly the case in Italy and Spain. It seems that at least some EU countries may have fallen victims to their own, decades-long success in the fight against infectious diseases. They faced this unexpected pandemics with few experts that could have had any experience in these events. Asian countries, as well as Canada, have had enough recent experience with SARS and MERS, but some European countries seem to have forgotten how to fight infectious diseases. If it were not for the legacy of the great Croatian epidemiologist and social medicine expert and global public health pioneer Andrija Štampar, and the relatively recent war in Croatia, it is difficult to say whether or not Croatia would be as ready as it has proven to be.

Another thing that likely undermined the Italians response was that no one before Italy, in fact, could have seen how fast COVID-19 was spreading freely among the population. The absolute greatest danger of COVID-19 is its accelerated, exponential spread when it breaks through the first line of defense. However, no-one had the opportunity to study this thoroughly before it reached Italy. Previously, only the Chinese in Wuhan and the Iranians had experienced the free spread of the infection. After five days of monitoring the number of infected, the Chinese had to quarantine Wuhan, and further 15 cities a day later, in order to contain the virus. They did not know how many infected people were outside of their hospitals. For Iran, however, no one knew exactly what was happening there, as that country is significantly isolated internationally due to political reasons. The Koreans, however, had a limited local epidemic but not an uncontrolled free spread - they caught the virus using their first line of defense.

That’s how the Italians ended up becoming the first country in the highly developed world to monitor their epidemic spreading uncontrollably among the population. The only estimate of the rate of spread of the virus to date has been in the scientific work of Qun Li et al. from the 29th of January, published in the New England Journal of Medicine. However, it was difficult for them to subsequently determine R0 parameter on the first 425 patients in Wuhan. Their estimate of the R0 for COVID-19 was 2.2, but with a very wide confidence interval - from 1.4 to 3.9. It's a bit of tough luck again that they calculated the lower bound of the confidence interval to be 1.4 exactly, because this figure is well known to all epidemiologists. It's the rate of the spread of seasonal flu in the community. It should come as no surprise that many epidemiologists would guess that, with more data, R0 for COVID-19 would start converging more towards 1.4. Unfortunately, the more recent data suggests that R0 is more likely to lean towards 3.9, implying an incredibly fast spread. Thus, the greatest danger of COVID-19 remained unrecognised in Italy until the 8th of March quarantine measures. At least 100 times fewer people would be dying in Italy these days had they declared a quarantine for Lombardy two weeks earlier than they did.

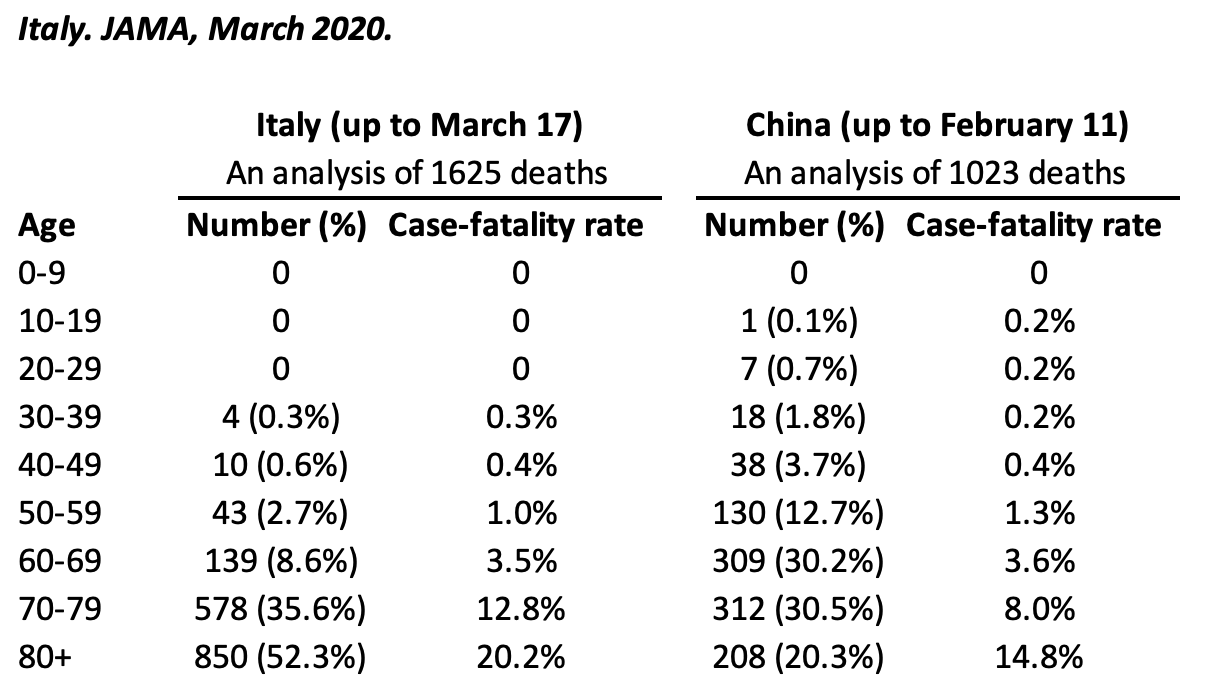

Just a few days ago, the JAMA journal published another extremely useful piece of scholarly work, authored by Odner et al. Their contribution finally provided answers to three great unknowns about COVID-19. Many myths about the situation in Italy have been present in the media since the very outbreak of the epidemic, but thanks to just one simple table, today we can finally dispel them all.

The first is the question that has plagued us all for a long time - how dangerous is COVID-19 for younger age groups? It is clear that the media will tend to single out individual cases of death in younger people, as they are of most public interest. However, it’s interesting that until recently, we didn’t have decent data on this. The first reason was that the Chinese Centre for Disease Control reported all deaths in Chinese epidemic using age group structure that contained a very large age group of "30-79 years". It only separated children up to 10 years, then adolescents up to 20 years, then 20-29 year-olds, then this huge group, and then those who were 80 years of age or older. That’s why the work of Odner and colleagues is commendable, as they made an effort to divide this large group into 10-year age groups. This finally allowed a comparison between the first 1,023 deaths in Wuhan (up to the 11th of February) with the first 1,625 deaths in Italy (up to the 17th of March). The comparison is shown in the Table 2 below. It gives us some very important insights.

Firstly, in Italy, more than half of the deaths initially were among people who were older than 80 years of age, and a total of 88% of the deaths occurred among the persons over 70 years of age. So, contrary to the impression that individual media reports can easily make, COVID-19 is a very dangerous disease mainly for the old people. Moreover, a study by A. and G. Remuzzi in the March 2020 issue of Lancet showed that, among 827 deaths in Italy, the vast majority of those people were already severely ill with underlying diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and malignancies. This is what epidemiologists expected, because a more severe flu would have had a similar effect if there was no vaccine available. However, I doubt that the general public have the proper insight into this issue from many media reports.

Secondly, it was suggested in the media across Europe that the virus in Italy may have mutated and become much more dangerous. However, Table 2 shows that death rates by the age of 70 are practically the same in China and Italy. Then, although the case fatality rate appears to be about 50% greater in Italy than in China for the age group 70-79, this does not suggest that the virus may have mutated. It is known that in Wuhan, many of the affected with a severe clinical presentation of COVID-19 could rely on the two newly built hospitals and respiratory aids that the military had brought in from other parts of China. They also had medical teams coming in from other provinces. In Italy, however, there were not enough respirators for this age group, and there weren’t enough doctors either, as many of them themselves became infected. For those two reasons I would, in fact, expect even a larger difference between Italy and China than the one we’re seeing, so I would not attribute this observed difference to the impact of the virus itself. And finally, the reported difference in case-fatality rates for the oldest age group should also not be attributed to the virus. It is more likely a consequence of the fact that Italians of Lombardy live, on average, longer than the Chinese of Wuhan. Therefore, there are significantly more people in the oldest age group in Italy, ranging to much higher ages, so the two oldest groups are not really comparable. The average age of the Italians in the age group "80 years or older" is significantly greater than the average age of the oldest Chinese age group. Therefore, the table shows practically equal death rates across all age groups, on sufficiently large samples, meaning that the virus didn’t mutate in Italy from the virus we see from Wuhan, at least not until the 17th of March, 2020.

TABLE TWO: Adapted from: Graziano Onder et al. COVID-19 Case-Fatality Rate and Characteristics of Patients Dying in Italy. JAMA, March 2020.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly - this chart has now made it quite clear that COVID-19 does not, in fact, kill people under the age of 50 unless they have some sort of underlying disease, or some unknown "Achilles heel" in their immune system that makes them particularly susceptible to the virus. There are such cases with every infectious disease. They are also present during the flu epidemics, but they are extremely rare. This suddenly gives us another possible quarantine strategy, where children and those under 50 years of age could first emerge if they don’t have any underlying illnesses. Here, after this table, it already seems like we are beginning to have an increasing number of options to get out of quarantines and learn to live with this virus until the vaccine becomes available. However, at least a few more studies need to be carried out to confirm that this age group can be substantially protected, to provide reassurance that the virus is not becoming more dangerous for those younger than 50 years old, too.

There is another strangeness to the situation in Italy that will not be intuitive to the general public. The actual number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 in Italy will not be possible to estimate for several months after the epidemic finally ends. Namely, at present, due to the sole focus on the epidemic, all of the cases of death of very old people who have been diagnosed using a throat swab have been attributed to COVID-19. However, once the epidemic is over, it will be necessary to compare the deaths in individual areas of Italy with the average for the same months in the previous few years. It could be shown that a part of the already ill would have died in the same month or year even without being infected with the new coronavirus, and that COVID-19 accelerated this inevitability by a few weeks or months. In this case, the so-called "reclassification" of causes of death will need to be carried out. The deaths observed during the epidemic in Italy will be attributed to underlying diseases in accordance with expected levels, and only those above expected levels will be attributed to COVID-19. This could ultimately reduce the number of Italians who actually died of coronavirus and otherwise would not have passed away that year.

This article provides an explanation from the epidemiologist's point of view for everything that has happened so far in Italy, and then followed in Spain and other European countries where COVID-19 has expanded through ski resorts and football games. Simply, a combination of an early relaxation, a possible inexperience in the management of infectious diseases, a systemic lack of expertise in the field, a possible evasion of immigration regulations, and a series of further misfortunes and human omissions have all led to the late withdrawal of Lombardy into quarantine. This allowed for a large number of people to be infected and severe illnesses led to death due to respiratory failure. In 88% of cases, people over 70 years of age died, who, in the vast majority of cases, had underlying illnesses already. But this is an analysis based on the first 1,625 deaths in Italy, and by the time of this writing, there are now more than 10,000 dead. Given the size of the population, this would correspond to 670 deceased in Croatia, which means that in Italy it is more than 100 times worse than it is in our country. This difference may be attributable almost entirely to a two-week quarantine delay.

These days, the people of Italy, Spain and other European countries are suffering large losses because of the problem that the human brain simply cannot intuitively grasp the power of exponential growth, nor that two weeks of delay could make the difference between 100 and 10,000 deaths. Any physics enthusiasts will know that the great Albert Einstein once warned us about this - he said that interest rates, which lead to exponential growth, are "arguably the most powerful force in the universe," to which no black hole is equal.

This text was written by Igor Rudan and translated by Lauren Simmonds

For rolling information and updates in English on coronavirus in Croatia, as well as other lengthy articles written by Croatian epidemiologist Igor Rudan, follow our dedicated section.

Medical Team Flown from Zagreb to Lithuania to Help Croat Troops

ZAGREB, March 29, 2020 - A medical team was transported on Sunday morning on a government plane from Zagreb to Lithuania to help the Croatian contingent, deployed as a part of NATO's Enhanced Forward Presence Battle Group, after four Croatian servicemen in that Baltic country tested positive for COVID-19.

The Croatian government has also sent necessary medical equipment, drugs and protective gear, according to a press release issued by the defence ministry.

Seeing off the team, the Croatian Armed Forces chief-of-staff, Admiral Robert Hranj, said that the infected Croatian soldiers were well and were provided with good care. The four infected soldiers are exhibiting mild symptoms, while 39 more soldiers are in self-isolation. The second Croatian contingent in Lithuania consists of 187 members, including a physician.

Admiral Hranj said that the situation in Lithuania considering the outbreak of COVID-19 was similar to the developments in neighbouring countries.

The plane is expected to stop in Berlin to take on seven German military doctors whose task is also to provide medical assistance to NATO troops in Lithuania.

More coronavirus news can be found in the Lifestyle section.

Restricting Human Rights is Out of the Question, Says Božinović

ZAGREB, March 29, 2020 - Restricting human rights is out of the question, people are increasingly aware that the current situation is an emergency and extreme situation, which is why measures by the national civil protection authority are extreme, Minister of the Interior Davor Božinović said on Sunday.

"The institutions of this state, the government and the parliament, are functioning. The national civil protection authority is adopting decisions in line with epidemiologists' recommendations and they have to be implemented at the level of local civil protection authorities," Božinović, who heads the national civil protection team, said when asked to comment on President Zoran Milanović's statement that decisions restricting citizens' rights had to be adopted by a two-thirds majority.

Božinović said that during the current crisis, last Sunday's earthquake in Zagreb was a critical moment, when a large number of citizens went out and some left Zagreb, mostly for the coast, where medical capacity in the wintertime is not as good as in the rest of the year.

He explained that that was the reason why the authority had introduced a ban on leaving one's place of residence.

Božinović confirmed that a prison guard in Split had been diagnosed with COVID-19, that some of the people who had been in contact with him were in self-isolation and that the situation in Split was under control.

He said that 99 police officers were currently in self-isolation, and that four police officers were infected. Self-isolation measures have been lifted for 25 police officers.

More coronavirus news can be found in the Lifestyle section.

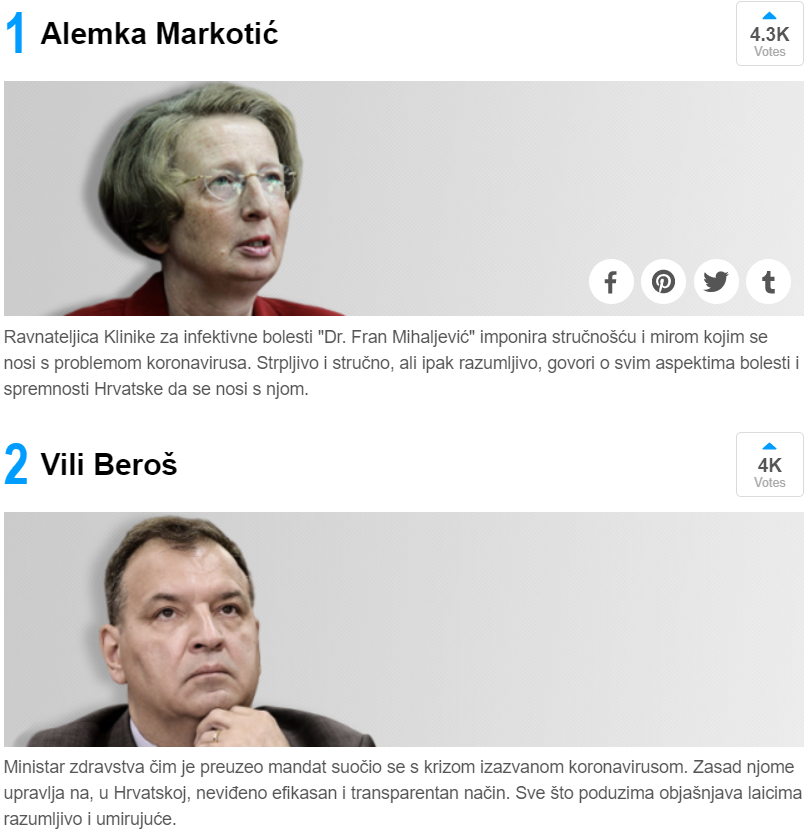

Alemka Markotic, the Healthcare Heroine Trying to Save Croatia from COVID-19

March 29, 2020 - She is the most popular woman in Croatia right now, and millions are grateful to Alemka Markotic are the rest of the National Civil Protection Headquarters for their outstanding efforts and communication skills.

I am not in the habit of writing articles praising people I have never met, but these are extraordinary times.

And another thing that has also been extraordinary has been the response and communication of the Croatian Government and the members of the National Civil Protection Headquarters, among whom is Alemka Markotic, Director at the Zagreb Hospital for Infectious Diseases, Dr. Fran Mihaljevic.

The level of communication and the no-nonsense advice and information has been exceptional to watch, and I applaud all who are working so tirelessly to protect us all.

Last week we featured Vili Beros, the new Health Minister, who only took up the position on January 28, 2020. His effectiveness in the position catapulted him to an unlikely position in the Croatian media for a serving government minister - the second most popular person in the country on the last Index.hr list of Top 20 Positive and Top 20 Negative people in Croatia.

But while Vili made it to number two, top spot was reserved for Alemka Markotic.

Here no-nonsense approach has produced some very memorable lines, which have rammed the message home to citizens that this is a fight that needs to be fought sitting at home in self-isolation.

"Does Croatia have enough ventilators?"

"That depends on the behaviour of our citizens."

And perhaps her most memorable like so far, just 8 days ago.

"If we want a corona party we will have it."

A lot of expats have asked me if I could write an article about Alenka Markotic and her background.

As I am not so familiar with that, I am extremely grateful to Iva Tatic for this piece below with more information about Alemka Markotic. As regular TCN readers will know, Iva has been contributing for us for several years part-time. Sadly, I had to put our cooperation on temporary hold, due to necessary cutbacks due to the crisis. Not only did Iva take the news in a professional and adult manner, she has since contributed several pieces to TCN for free, including this one. Bravo, Kolegice, much appreciated, and we look forward to having you back on board soon.

Alemka Markotić was born in Zagreb in October of 1964 (the entire nation of Croatia should get together and buy her a birthday present; we can organize that), but her education mostly took place in Bosnia and Herzegovina. She completed high-school in Zavidovići, and then Medical school at the University of Sarajevo, where she got her degree before the wars in former Yugoslavia started. Her post-graduate studies mostly continued at the Medical school at the University of Zagreb, where she managed to get a master’s degree in 1991, after which she dedicated herself to humanitarian work during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. She worked as a GP during the occupation of Sarajevo, and helped the Caritas war pharmacy and outpatient clinic. In 1994 she continued working for Caritas charity, but in Croatia, where she took the position of medical coordinator working with displaced people and refugees.

Her specialisation was in the field of clinical immunology, so her next job was in the now almost completely defunct Institute of Immunology in Zagreb. During her time there she managed to get a PhD, and completed a post-doctoral stay in the US, where she worked in the biosafety laboratories of the US Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases in Maryland.

In 2005 she moves to the Hospital for Infectious Diseases "Dr. Fran Mihaljević”, which is where she is the director since 2017, and which is the position she holds now, during the largest infectious crisis of our times.

She teaches at numerous universities in Croatia and abroad: University of Zagreb Medical School and Faculty of Food Technology, University of Osijek Medical School, University of Rijeka Medical School, Study of Forensics at the University of Split, and others.

Dr. Markotić has always been public and vocal about her religious belief, declaring that the is a practicing catholic and that she wouldn’t be able to do what she does, both now and during the war-times in Sarajevo, were it not for her faith in God.

Our thanks to all who are working with Alemka Markotic in the fight against corona.

You can follow the latest news on TCN in our dedicated corona section.

Union Tells Government to Leave Teachers Out of Its Plans for Wage Cuts

ZAGREB, March 29, 2020 - The Independent Union of Research and Higher Education Employees of Croatia said on Sunday that in addition to doctors, police and the army, employees in the education and research sectors should not be mentioned in public debates on possible public sector wage cuts either.

The union notes that unlike medical workers, civil protection, police and the army, the work of teachers from home, on which online education in the current coronavirus epidemic is based, is not visible to the public even though it requires greater and significantly different engagement on their part.

Interactive communication provides an individual approach to each student and apart from virtual classrooms and staff rooms, teacher-student communication is maintained also through closed groups, social networks and by phone, says the union.

"Work in the education system in the current crisis is much more complex and requires much more time than the usual classes - for teachers and students alike - even though it is not publicly visible like the usual work of educational institutions," the union says, noting that the system of education is functioning well in the current crisis and that it expects that work to be recognised not only by students and their parents but also by the broader public, notably the government.

More coronavirus news can be found in the Lifestyle section.

Koronavirus.hr Official Update, 14:00 March 29, 2020 - 713 Cases, 6 Fatalities

March 29, 2020 - The official Koronavirus.hr website has a new service in English - a comprehensive coronavirus daily update.

A total of 713 people infected with coronavirus was recorded on Saturday in Croatia. 52 people recovered. Six deaths have been recorded.

5.900 tests have been conducted.

Starting 00:01 Thursday, March 19, a new series of measures takes place to ensure stricter social distance and reduce the possibility of spreading the virus among population. Please be reminded to comply with received personal hygiene instructions and to keep social distance between individuals: a distance of 2 meters is required to be kept indoors and a distance of 1 meter outdoors.

All non-essential activities are closed in order to protect senior citizens and those chronically ill – as far as it is possible.

We remind you that the best defense against this virus is to maintain personal hygiene and avoid close contact. Therefore, these measures forbid all activities with large number of people in close contact and gathering of more than 5 people.

The wide range of facilities and stores are not closed to ensure normal supply of food and goods. Freight traffic and supply lines operate regularly. An agreement with countries in our neighborhood has been reached to ensure supply and transportation.

Employers are required to organize work from home for their employees, arrange teleconferences, cancel all business trips and forbid workers with acute respiratory illness from coming to work.

The local civil protection headquarters will be in charge of implementing new measures.

A temporary ban on the movement of civilians across borders is also enforced, with an exception of healthcare professionals, elderly care professionals, cross-border workers, police officers, civil protection teams, military personnel, international military personnel, passengers in transit. This permission will need to be granted individually.

Croatian citizens will be allowed to return to the Republic of Croatia and EU citizens will be able to return to their countries of origin.

All facilities allowed to operate will have to comply with the measures given by the Croatian Institute for Public Health. Croatian Institute for Public Health will issue transport recommendations valid at the national level.

It is highly important that people in self-isolation strictly follow the given instructions on self-isolation.

As of Wednesday, March 18, special measures, which will take effect over the next 30 days, will have a significant impact on the elderly as the most vulnerable group. The measures aim to protect the elderly citizens from infection.

Remember: the best protection is to follow all given prevention measures and to avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth.

You can find all materials, conferences and announcements on official Youtube channel here.

Afternoon conference for Saturday, 28th of March (yesterday) is available here.

For the latest official information from the Koronavirus.he website, click here.

For the latest TCN coverage of COVID-19 in Croatia, visit our dedicated section.

Mirko Sardelic PhD Interview: History of Pandemics: Lessons to Apply to Corona Crisis

March 29, 2020 - A look at the history of pandemics and what we can learn and apply to the current coronavirus pandemic. TCN's Aco Momcilovic interviews Mirko Sardelic PhD.

Interviewer: Aco Momcilovic, psychologist, EMBA, Owner of FutureHR

Interview with Mirko Sardelic, PhD, Research Associate at the Department of Historical Studies HAZU, Honorary Research Fellow of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions (Europe 1100-1800) at The University of Western Australia; formerly a visiting scholar at the universities of Cambridge, Paris (Sorbonne), Columbia, and Harvard.

Intro: The world is facing one of the biggest global crises of our lifetime. Many individuals are feeling that this is an unprecedented event that will have a major impact on their lives and society. And we are definitely on the verge of a new era; the future will be quite challenging. Therefore, this is a good time to reflect and observe this current situation in the historic context. How much do we know about similar situations, and is there something we can learn and apply to this situation? Some of the answers and comments will hopefully be provided by my friend and history expert – Dr Mirko Sardelic.

Q1: In written history, do we have records of similar pandemics? How many of them were on a comparable level to this Coronavirus situation?

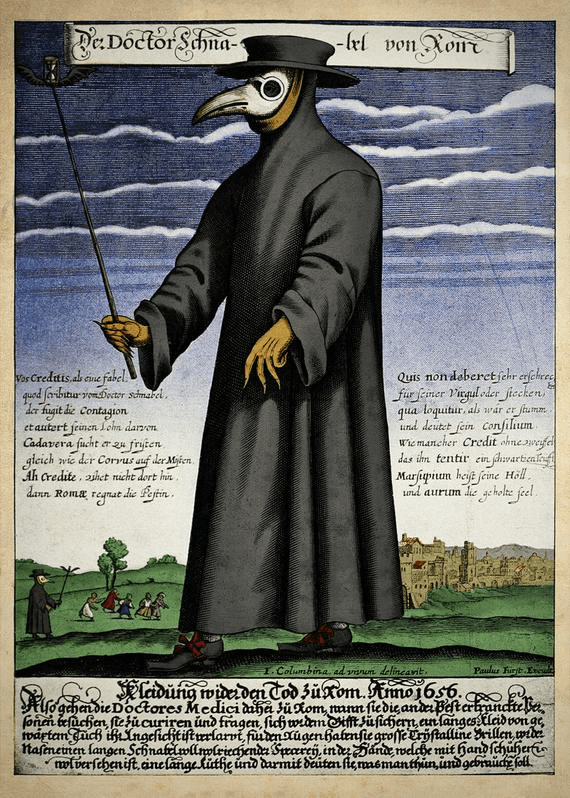

Human history is quite rich when it comes to pandemics. The one we are experiencing today – from what has been known so far (though we must be aware that the pandemic has just started) – may arguably appear as a much milder version of what must have been happening during medieval and early modern plague epidemics. The Justinian plague (541-542 AD) killed millions of people in the Mediterranean zone and beyond. The plague of 1340-50s (known as the Black Death) killed more than 100 million people worldwide, reducing the world’s population by one quarter, and cutting the population of Europe in half. For the next several hundred years deadly outbreaks and epidemics of plague-ravaged helpless humanity in every decade. The last recorded plague in Europe was in 1815. In no time, the first recorded major cholera pandemic started in 1817, and by 1823 had killed millions spreading from India to Southeast Asia and towards Turkey and south Russian lands. There were five major pandemics of cholera in the 19th century alone. In short, every generation has experienced or at least heard of terrible deaths by microbiota. (the Croatian language keeps the phrase used for horribly filthy places one should avoid by all means: ‘kuga i kolera’ – meaning plague and cholera: our folk immortalized the two in this superlative of the adjective ‘filthy’.) Nonetheless, the fact that there were so many horrifying epidemics does not mean we should underestimate this one, as it looks quite serious.

Q2: First scientific data indicates that COVID 19 is more lethal than ‘ordinary’ flu, and estimations of the death rate range between 1 and 3.5% usually. While still counting the number of infected in hundreds of thousands, and the number of dead in tens of thousands, it is clear that numbers are going to be high. But again, it seems that they were nowhere close to the devastating epidemics that raged before. What were the deadliest diseases we had in the past?

What the world knows by the name of Spanish flu (that had very little to do with Spain) infected ca 500 million people – which means almost every third inhabitant of Earth was infected – and it took approximately 50 million lives. One might estimate that the death rate was ca 10%, although this number varied, e.g. some native American communities were almost completely wiped out, most probably because they had never been exposed to similar viruses to which Eurasian populations have acquired some resistance. The Bubonic plague’s death rate was approximately 50% and many contemporary sources claim it was more merciless with younger people. One should, however, bear in mind that the diet, hygiene and overall standard of 14th-century people was quite modest and inadequate, by any contemporary criterion. Very recent Ebola outbreaks had mortality rates ranging from 20 – 70%, but have never developed into a pandemic, due to the nature of the virus that can survive for only a short time outside bodily fluids. It seems that there is often a kind of balance between the contagious and deadly aspect of a virus – but it is epidemiologists who should be explaining this.

Q3: Modern science, and the context of the world in the 21st century, will, fortunately, limit the damage of any disease. It seems that it is very hard for us to imagine the context in which people lived before, without modern medicine, scientists and other tools that we use today. Can you picture that for us?