Emigration from Slavonia? The View from Osijek University (VIDEO Interview)

December 10, 2022 - The perception of eastern Croatia is a region of emigration and economic decay. TCN visits the University of Osijek to catch the mood with students.

One of the things I like to do when I have time is to talk to the young people of Croatia to see how they see their country and their future, particularly in eastern Croatia, which is a magical land which is so misrepresented in Zagreb and treated almost like a handicapped cousin, one whose existence is acknowledged but kept firmly out of the public eye.

From the moment I first visited Slavonia back in 2014, I sensed that there was something wrong with this narrative. Yes, the emigration was significant, but so too was the desire to stay and build a better future, as well as infinite pride and hospitality. Slavonians really are a breed apart, in a good way. Lack of investment, lack of interest, and a public perception of war and hopelessness has come to characterise how people in the rest of Croatia see the region.

And yet, having travelled extensively in the region, my experience has been exactly the opposite. My tour of eastern Croatia in November, 2021, remains the best trip I have done in my 20 years in Croatia - read about it in Time to Tell the Truth about Slavonia Full of Life.

When I came back to Zagreb with wild tales of the east, what became immediately clear was the level of ignorance about eastern Croatia. As I explain in the video tour video above, I asked thee simple questions to 70 people in Zagreb about eastern Croatia - just one got all three correct, with 69 out of 70 unable to do so. Do you think you can answer the three relatively simple questions? Check them out in the video above after the video tour of the region.

But not only had I found a magical and relatively undiscovered tourism region, but the people I was meeting were all saying the same thing. The pace of emigration was halting, even reversing, and the number of opportunities I was coming across were growing by the day.

A year ago, I was surprised to meet a British businessman in my hotel, the excellent Maskimilien, in Tvrdja in Osijek. He explained that he had a Swiss drone company and was working with Orqa, the Osijek-based FPV drone company, which is leading the world in this emerging technology. A year later, I met him again. Orqa had since acquired his company, and he had bought a house and moved to Osijek to work within Orqa to put develop Orqa and its drone technology. It may be hard to believe for some, but Osijek is now home to the leading drone technology company in the world, and there are some VERY interesting visitors to Slavonia these days, given the events in Ukraine.

And Orqa is not alone - the IT sector in particular, is very vibrant. But I was more interested on this trip to get the views of the younger generation, and I am very grateful to Marija Lozancic for organising a seminar for me at the University of Osijek Faculty of Education on the subject How Travelling the World and Experiencing Cultures Helps Build a Media Career in Croatia.

The last time I spoke at a university, in Zagreb, just 9 students turned up. In Osijek, there were almost 50. Curious about their future plans, I asked how many planned to emigate on graduation - just 2. And how many were definitely staying? An impressive 25. Yes, the emigration had been terrible, but times are a changing. I asked for some volunteers to do a video interview after the seminar, and I am very grateful to the three young ladies in the video below, who were happy to share their views on life in Slavonia and their plans for the future, which include developing their new English-language blog, www.englishing.eu

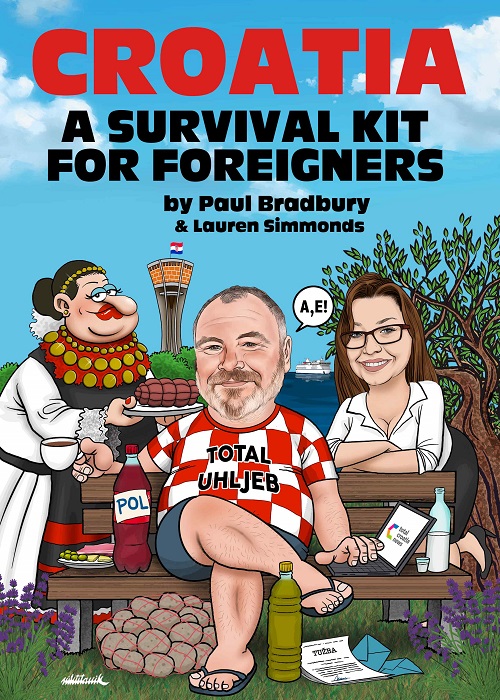

And wherever I went on my 3-day trip to the east this week, I was met with the traditional warmth and hospitality, but also a lot more positivity and feeling that things are changing regarding emigration. Turnout for our book promotion of Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners was bigger in both Osijek and Vukovar than it was in Zagreb, Split or Zadar.

(Presentation of Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners at Knjizara Nova in Osijek on December 6, 2022)

Eastern Croatia is a fantastic place which has been kept down for too long. If you have never been, I encourage you to visit. And if you think that it is a place purely of emigration and economic decline, you are in for a major surprise.

(Presentation of Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners at Vukovar City Library on December 7, 2022)

****

What is it like to live in Croatia? An expat for 20 years, you can follow my series, 20 Ways Croatia Changed Me in 20 Years, starting at the beginning - Business and Dalmatia.

Follow Paul Bradbury on LinkedIn.

Croatia, a Survival Kit for Foreigners is now available on Amazon in paperback and on Kindle.

300,000 Croatians to Have Their Free Health Insurance Cancelled

January 12th, 2022 - Those who have left Croatia but keep using Croatian public healthcare at the expense of the state will soon be removed from the HZZO database

As many as 300.000 Croatians could soon have their public health insurance policies cancelled by the Croatian Health Insurance Fund (HZZO), reports Novi list. Namely, Health Minister Vili Beroš has announced that the HZZO would be cancelling the policies of those insured whose residency or employment status does not grant them the right to free health coverage anymore.

Most of that list consists of citizens who emigrated in the last decade and now work and reside abroad, but retain their Croatian public health insurance at the expense of the state on the basis of being unemployed in Croatia.

A large number of such policyholders prefer to use the services of GPs or dentists when they visit Croatia, as they find it much more affordable than the equivalent service in the country they currently reside in. It’s estimated that two thirds of Croatian emigrants avail of their health insurance benefits in such a manner.

The HZZO states that a considerably large number of people benefit from the rights guaranteed by their public health insurance despite not paying the compulsory insurance contributions. The exact number could become known in a month’s time, once HZZO and the Croatian Employment Service (HZZ) have merged their databases.

All citizens who are not on file with the HZZ, but avail of the free compulsory health insurance on the basis of their unemployment status, will have their health insurance policies cancelled, as well as their dependents.

According to the director of the HZZO Lucian Vukelić, those citizens who are not registered with the HZZ as unemployed persons could lose their free health insurance policies as early as in February 2022, once the two institutions have signed the data exchange agreement.

In recent years, many Croatian citizens have left their homeland in search of work; while the number of HZZ applicants dropped significantly as a result, they mostly remained on file with the HZZO and held onto their free health insurance.

A number of Croatian emigrants were removed from the HZZO database in the summer of 2021, after a data exchange with the Ministry of the Interior showed which citizens had cancelled their residency in Croatia.

According to the HZZO, at present it’s nearly impossible to find out which Croatian citizens work in other countries where they also pay their health insurance contributions and where they should thus avail of public healthcare as well. Even though it’s illegal to have public health insurance in two countries simultaneously, there still doesn’t exist a unified EU database that would reflect where citizens have contributory health insurance and use public health services.

‘Considering that there’s a bunch of different insurance providers in most countries, it’s impossible to obtain the data. You would have to search all over Europe for each policyholder individually to find out if they’re insured in a certain country. It so happens that no one in Croatia ever cancels their health insurance; [employers in] most EU countries are obligated to insure their workers upon employment, and so we end up with an enormous number of people who work abroad and are insured in Germany, Austria or Norway, whereas in Croatia their public health insurance remains covered by the national budget’, said Vukelić.

The HZZO does not have the exact figures regarding potential savings for the national budget if Croatians who are not factually unemployed were removed from the HZZO’s list of unemployed policyholders.

However, if we were to consider the 300.000 people in question, based on the health contribution rate of 16.5% of a monthly gross salary of e.g. HRK 5,000, the state is HRK 2,7 billion out of pocket each year. This does not even take into account the annual costs of health services in Croatia that such policyholders avail of.

The HZZO will also look to cancel the policies of Croatian citizens who have not left the country, but use the benefits provided by their health coverage even though they are not paying the contributions.

An example of this are undeclared workers who neither pay for the coverage nor are they on file with the HZZ, but retain their free health insurance. Such persons will need to register with the HZZ and find legal work, i.e. pay the relevant taxes and contributions.

https://www.novilist.hr/novosti/hrvatska/hzzo-cisti-evidenciju-besplatno-osiguranje-moglo-bi-izgubiti-300-000-ljudi-radi-se-mahom-o-iseljenicima/

Ljerka Bratonja Martinović

AFP Uses Croatia as a Warning Amid the Migration Problem in the Balkans

January 2, 2022 - Young people from the Balkans migrating to other European countries in search of opportunities and better salaries is already a well-known story. However, it could be more serious than it seems and AFP uses Croatia to warn about this phenomenon.

The renowned Agence France-Presse, the oldest journalistic agency in the world, published today an investigation on the migration crisis affecting several countries in the Balkan region. After their independence in the 90's, many countries in the Balkans progressively found the way to development and economic openness. However, and as reported by the AFP, to date they have not been able to compete with the opportunities and salaries found in other European countries, and the statistics are difficult to contradict.

One of the problems, they report, is the abysmal development difference in towns and localities far from the capital. And that is the case of Valandovo, a town located 146 kilometers from Skopje, which now stands out for its streets full of shops and abandoned homes, and where young people leave in large numbers in search of better opportunities.

North Macedonia has shed 10 percent of its population in the last 20 years. Around 600,000 Macedonian citizens now live abroad, according to World Bank and government data.

Abysmal economic growth and a lack of investment have clobbered the country, now home to just 1.8 million people, in its 30 years of independence.

"If you have a little over 2.4 million citizens and more than a quarter have left, then you have to seriously be worried about what is happening," says Apostol Simovski, director of the country's statistics office. "The spirit of young people has been systematically destroyed," Pero Kostadinov, the newly elected 33-year-old mayor of Valandovo tells AFP. "The enthusiasm to fight and stay home has been lost."

North Macedonia has sought to join the European Union in the last decade, and thus hope for a better future for the country and its youth. But the aspirations of the small Balkan country have been hampered by the refusal of Bulgaria and Greece, who have tried to convince other member states through doubts about the true possibility of North Macedonia to join. Currently, the salary for those who decide to stay averages 470 euros. Many young Macedonians now believe that "it is better to be a slave for 2,000 euros in another country, than for 300 euros at home," as is commonly heard.

The reality is similar in other countries such as Albania, where approximately 1.7 million people (almost 37% of the population) have migrated in the last 30 years according to government estimates. For Ilir Gedeshi, an economics professor in Tirana, the reasons behind the mass migration in the Western Balkans are not only due to economic reasons, but social factors are also decisive.

The analysis becomes more interesting and worrying when one takes into account the reality of a country like Croatia, which joined the European Union nine years ago. Although the economic, social, and political development in the country since its independence is highly palpable, the migratory phenomenon is not unlike those of other countries in the region. While countries such as North Macedonia, Serbia, Kosovo, Albania, or Montenegro hope that their fortunes will be reversed by joining the European Union, what happens in Croatia should serve as an example, warns AFP.

Since joining the bloc in 2013, its population of just over four million has shrunk nearly 10 percent in a decade, according to preliminary census findings.

The United Nations projects that Croatia will have just 2.5 million people by the end of the century. Demographers warn that the country's tiny population may lack the resilience to weather further losses.

In December, Zagreb sought to reverse some of the brain drain by promising Croatian expatriates in the European Union up to 26,000 euros ($29,000) to return and start a business.

But for some areas, it may already be too late.

"For sale" signs litter the eastern region of Požega, one of those hardest-hit by war in the 1990s. More than 16 percent of the area's population of nearly 80,000 have left in the past decade, official figures show.

"In my street one-third of the houses are empty," said Igor Cancar, 39, from nearby Brestovac.

They include his sister who moved to Austria with her husband and two children, along with most of his close friends.

"If we want young people to stay, we need a kindergarten and help them build a house," Cancar added.

"The last train is leaving, and we are doing nothing but standing on the platform and waving."

For more, check out our politics section.

The Realities of Croatian Emigration to Ireland, Part II: Work

Continuing our series on Croatian emigration to Ireland, a look at the topic that drives most people to emigrate in the first place: jobs, paychecks and everything in between

To paraphrase a pop art icon, just what is it that makes Ireland so different, so appealing? To any Croatian person frustrated with their miserable economic prospects, it’s always been all those jobs that are readily available. It’s so easy to find work!, people will tell you. And it pays well!

After three years in Ireland, I have a bit of perspective in this regard, so... Let’s unpack that.

1. The land of opportunities

Ireland was widely known for having the fastest-growing economy in the EU year after year since 2014… until a pandemic threw a wrench in it. Much like in the rest of the world, Covid-induced lockdowns caused unemployment to soar - from 5.9% in July 2019 to 19.1% in July 2020. The trend kept up this year as well, and things only started to look up after the reopening of outdoor hospitality in summer.

The labour market in Ireland is not expected to recover to pre-pandemic levels of employment until 2024. Not the best time to set sail for Ireland in search of a better life, perhaps. It’s quite a depressing picture, and the prospects for those living in Ireland don’t seem promising at the first glance. And yet… Despite all troubles in the last 18 months, there was a 56% increase in job vacancies on the Irish employment market in Q3 2020 after the initial crash. A year later, and a quick look at the leading job sites shows there’s no shortage of work available.

Markus Spiske / Unsplash

Let’s start with the group that seemingly made the best choices in life. Anyone working in IT would likely score a job in the time required to read this article - tech tops the list of leading industries in Ireland, and not without reason. Low corporate tax and the constant influx of skilled international workers have foreign investors flocking to the only remaining English-speaking EU country. Google, Twitter, Facebook, Microsoft, PayPal and other tech giants set up their European headquarters in Dublin; Apple has a base in Cork. Engineers, developers, data scientists, analysts and the like will always have their pick on the market as IT experts remain highly sought after.

For the rest of us mortals, there’s the wide umbrella of the tertiary sector. Most immigrants to Ireland, including Croatians, are likely to seek employment in hospitality, hotels, customer service, healthcare and assisted living, beauty and wellness, grocery retail, repair and maintenance, etc.

Etienne Girardet / Unsplash

Etienne Girardet / Unsplash

There’s a massive labor shortage across other industries as well: transport, construction, manufacturing. In recent years, Irish employers have expanded their search to the continent, hosting open days in several Croatian cities at a time in hope of attracting a skilled workforce. Nurses and caregivers, professional drivers and warehouse operatives, all are in constant demand.

2. Dynamic, fast-paced environments

There are three main ways to find a job in Ireland. Recruitment agencies make the process more streamlined and less stressful for jobseekers who have only just arrived and have yet to get acquainted with the intricacies of the job market. Depending on the industry and the employer they represent, some agencies will also assist new hires with relocation and paperwork.

There’s also the tried and tested ‘door to door’ method - you’ll often see a ‘staff needed’ sign on display when entering a shop or a deli. It’s not unheard of to print out a few copies of your CV, walk around town for a while and land a job in a day or two.

Looks about right. / Markus WInkler, Unsplash

And finally, there are job sites such as Indeed, Monster and Jobs.ie. They’re probably the most popular method of seeking employment and also a nice way to suss out what the job market’s like at any given time of year. Take the holiday season, for example. With Christmas fast approaching and shoppers about to go berserk, there’s a noticeable uptick in demand in customer-oriented occupations.

Anyone who’s ever worked in the lower tiers of hospitality, retail or any kind of customer service would tell you that for the most part, it’s miserable, soul-sucking labour. Well, HR departments bend over backwards to make it seem otherwise, coming up with dramatic ads that often obfuscate what the actual position entails.

It’s a wild wasteland of ‘vibrant’, ‘high-energy’, ‘fun’ work environments.

A prospective cashier will thus have an ‘exciting opportunity’ to ‘become an ambassador’ for the brand’s business. Hotels offer ‘fantastic new vacancies’ for ‘accommodation assistants’ and list ‘ambition to develop’ among the main prerequisites to join the cleaning staff. Gone are the days of straightforward job descriptions. Job titles are replaced with ludicrous synonyms that are meant to sound more exciting or more important, but end up being neither: call-centre agents have evolved into support professionals, advisors, specialists, executives and gurus.

Speaking of gurus, it’s getting hard to discern whether you’re about to join a workplace or a cult. ‘What does living fully mean to you?’, asks an ad for a reservations agent. It’s a lot to consider. As you become part of a ‘close-knit family’ that’s ‘customer-obsessed’, you’ll be ‘resilient and disciplined’ and - my favourite - ‘take instructions with enthusiasm’.*

Ian Schneider / Unsplash

It’s a heavy burden to carry, suddenly becoming an executive or a spiritual leader where you thought you’d only have to answer the phone. Expectations are piling up, with Irish employers demanding years of experience, strong initiative, attention to detail, resilience, discipline, emotional intelligence, warm personality and full flexibility to work shifts within a 16-hour window with schedules changing at a moment’s notice. All things considered, if you see ‘excels in a dynamic, fast-paced environment’ on a CV, it’s code for ‘capable of doing seven things at once under pressure and accustomed to dealing with verbal abuse’.

This is not exactly a groundbreaking revelation, I know - and none of it is exclusive to Ireland. Our tourism-oriented country is heavily dependent on the service industry, and nonsensical corporate language slowly seeps into the Croatian job market as well.

The thing is, that ‘fantastic new vacancy’ in Dublin pays three times as much as you would get for the same shitty job in Croatia. In fact, you get paid two to three times more for low-skilled work in Ireland than you would be in a job requiring a university degree back home.

Emigration 101.

3. The cost of living

The national minimum wage in Ireland is €10.20 per hour (before tax), which is set to increase to €10.50 from January 1st, 2022. To put this in Croatian terms, an average single person working full-time on a minimum wage will soon be earning around €1600 per month net.

At present, the monthly minimum wage in Croatia is roughly €450 net (3400 HRK), set to increase to €500 (3750 HRK) next year.

No wonder the grass seems greener on the other side. Average and median pay in Ireland is even higher, but the majority of foreigners moving to Ireland for work won’t start with an average salary. I’m purposely using the minimum wage as an example, as I feel it’s a more realistic comparison between the two countries that also helps us consider what the bare minimum can get you here and there.

There are many factors at play, of course, and we can’t just straight up compare apples and oranges. What about expenses? It’s not just wages that are higher. I dedicated a whole article to the housing crisis in Ireland, and it’s true that rent alone will eat up a substantial portion of your paycheck. Childcare and car insurance are no joke either. Bars and restaurants are more expensive. So is tobacco. Entertainment costs more in general: nightclubs, music, theatre, cinema. Don’t get me started on hairstylists. It adds up, and if you covet the finer things in life or have any vices to sustain, you’ll need to start climbing the career ladder asap.

Markus Winkler / Unsplash

Here’s the catch, though: in proportion to wages, basic needs cost less in Ireland than in Croatia. To put it another way, less time is spent working in order to afford certain essential goods or services. Rent aside, okay.

Food is the worst offender. Even though we’re all aware that food prices are inflated in Croatia, the extent of it doesn’t really hit you until you’ve returned from Ireland where you earned three times as much, yet groceries somehow cost the same or less than back home. These days, you’ll find us haunting supermarket aisles and woefully voicing our thoughts to no one in particular. ‘Ha ha, look, coffee costs the same as in Tesco. Wait, 25 kuna for oat milk? That’s almost doub- 30 kuna for budget brand rice? 30?? FOR RICE??’

Then there are utilities. Our monthly bills (internet, gas and electric) were only marginally higher than in Croatia. Also, water supply is free. No water bills. Wild.

We try not to be those people who return to Croatia only to start every sentence with ‘well in Ireland, it was like-’, but some days are harder than others.

Once you’ve covered all your basic living expenses, outrageous rent included, you can do a whole lot more with your discretionary income than you could in Croatia. I moved to Ireland in late 2018; in the following year, I paid off a small debt, took a total of 8 international trips ranging from a weekend to 2 weeks in length, and was able to afford all the things I wanted without having to cut corners, only earning a bit more than the minimum wage for the bigger part of the year.

The same job in Croatia would pay enough for me to live month to month and take trips to the local bar once a week. Which brings me to my next point...

4. Dignity and (self)respect in the workplace

You go through a certain transitional period when you move from Croatia to Ireland and start making a steady income. It’s called ‘boy do I have a shitton of money all of a sudden’, lasts anywhere from six months to a year, and involves a lot of frivolous spending. No more depriving yourself of nice things in the name of electric bills! You can now have both - and more! Once the adjustment process is over, you sober up, start budgeting and set up a pension fund.

Jokes aside, viewing your job, your salary and your worth objectively is a skill that takes a while to master. Salaries are discussed in annual amounts before tax, unlike the Croatian monthly net ways we’re used to. Coupled with the higher living standard in general, this makes every figure sound desirable at first. You don’t know the nuances and implications of 19k, 25k, 35k - it all seems like a lot.

What about the kind of work you’ll take on? Suppose you’re not highly skilled in one specific field. If you’re emigrating for economic reasons, you won’t be terribly selective when you first arrive and if needed, you’ll aim lower than usual until you get settled.

How low would you go, and how long would you stay there? The former is a no-brainer; an entry level position will suffice to get you going even if it involves low starting pay. You want to sort out all the paperwork as soon as possible, rent needs to be paid, and honest work is honest work. The latter, however, is where things get complicated. What do you want to make of yourself? How do you measure success?

Alex Kotliarskyi / Unsplash

Take my example. I wanted to get the ball rolling as quickly as possible, so I took a job in customer service I was overqualified for. It soon became apparent that starting over from the bottom creates a certain dichotomy in your self-awareness. The person you are in your home country and the person you are in emigration only partially overlap, both sides engaging in constant dialogue: I have a master’s degree, but take calls for a living. I earn a Croatian MP’s salary taking calls for a living. This is not what I want out of life. This allows me to live quite a comfortable life. I used to declare I would never leave home. I made a conscious decision to be here. And so on, and so on. This unavoidably messes with your head for a while. It’s an uncomfortable process.

Granted, I moved up with time and changed roles within the same company. My salary increased as well, I picked up a few new skills, and the camaraderie we had going on the floor made the daily grind more palatable. The work itself, however, remained unfulfilling, and in normal circumstances, I wouldn’t think twice before looking elsewhere for something better suited to my skills and interests.

But since I wasn’t planning on staying long-term, I let inertia take over. This is okay!, I thought, this is okay for the time being!, all the while not exactly knowing how long that time being would last. It ended up lasting longer than I expected. I built a good reputation for myself, had amazing colleagues and a great rapport with my superiors, paychecks were rolling in, and I got comfortable.

My salary was modest for Irish standards, but served me well enough and I wanted for nothing. I felt valued. This seems to be the case with plenty of other people I’ve met: well-educated, competent individuals, some with a lot of experience under their belt, accepting positions well below their skill level and staying, as those positions awarded them a better quality of life than a managerial rank in Croatia ever did.

This is not to say that employers in Ireland shouldn’t pay their workers more, or that we should settle for peanuts and never aim higher as long as we can get by - on the contrary. But it answers the question of why so many people adjust their criteria significantly when they move to a foreign land to seek work. I’ve seen quite a few vicious articles and comments disparaging people who left Croatia for Ireland ‘only to scrub toilets in exile’. How dare they sell this as a success story? They weren’t willing to do any scrubbing until now, Croatian toilets not good enough for them?

Not when they don’t earn you a living, they’re not. Irish toilets are much better in that regard, along with their offices, call centres, hotels, warehouses and supermarkets. Regardless of profession, workers are respected in Ireland, overtime is paid without fail, and paychecks show up on bank accounts like clockwork. It’s not all milk and honey, but for the most part, the business culture is much healthier than in Croatia. It was nice to experience living in a country where entrepreneurship is encouraged, and breaking into the public sector isn’t the ultimate career goal.

This is a highly subjective topic, and there’s no universal experience which all Croatian emigrants share when it comes to labour. I don’t want to make it seem like all of us work menial jobs and never move up in the world. Some chase promotions, some start businesses, some make the big bucks, some return home disillusioned after a few weeks. Most just want to live a dignified life and then take it from there - and Ireland, on her part, sure provides plenty of opportunities for growth.

*Everything in quotation marks is a direct quote from various advertisements on Jobs.ie accessed on 1/11/2021.

Read the first part of the series on Croatian emigration to Ireland - accommodation.

For more news and features from the Croatian diaspora, follow the dedicated TCN section.

Mass-Scale Emigration From Croatia Has Led To Rise in Corruption - Study Finds

ZAGREB, 15 June, 2021 - The emigration of Croatian citizens, in addition to having incalculable implications for the country's pension, education and health care system, has also lead to a rise in corruption in Croatia, Večernji List newspaper said on Tuesday, citing a study by Tado Jurić, a political scientist and historian from the Croatian Catholic University.

The study showed that corruption and emigration were interrelated.

Jurić compared corruption and migration trends from 2012 to 2020, notably the number of Croatians who emigrated to Germany, the country where most Croatians go to in search of work and a better livelihood, and the ranking of Croatia in the global corruption index, and found that corruption was more pronounced when the number of people who left the country was higher. Croatia ranked 63rd among 180 countries included in the corruption index in 2019 and 2020, and 50th before the emigration wave reached its peak.

"Common sense says that if people who are not involved in corruption networks emigrate and those who stay are involved in such networks, corruption activities will be even easier to carry out and more frequent. If critics leave, all the better and easier for those criticised," Jurić says, adding that corruption is deeply rooted in Croatian society and has become a parallel system that undermines the economy.

"Corruption has done even more damage to the Croatian national identity, the sense of unity and solidarity, and to Croatian culture in general than it has done to the economy, which is unquestionably enormous. The main negative effect of corruption affected the country's human resources and political stability. In Croatian society, corruption has become a privilege of the elites, but so-called major corruption, political corruption and clientelism should not be confused with so-called civil corruption.

"So-called elite corruption has given rise to a special phenomenon in society which could be called 'a revolt of the elites'. It is the elites that use the media for their everyday protests against the media, citizens and institutions, making citizens accustomed to the practice that they should not express their dissatisfaction with politicians, but that politicians should express their dissatisfaction with them," Jurić said.

The study shows that 65.3 percent of 178 small, medium and large companies polled said that corruption has been on the rise in the last five years, while 32.4 percent believe that there has been no significant change.

For more about politics in Croatia, follow TCN's dedicated page.

Despite Pandemic, 26,000 Croatians Moved to Germany in 2020

ZAGREB, 29 March, 2021 - In 2020 Germany saw the lowest increase in the number of foreigners in the last ten years, however, despite the pandemic, more than 26,000 Croatians emigrated to Germany last year, show statistics published by the Federal Statistical Office in Wiesbaden on Monday.

The net increase in the number of Croatian citizens with residency in Germany in 2020 was 11,955 to 426,845.

From 1 January to 31 December 2020, 26,335 Croatian nationals emigrated to Germany while 10,305 Croatians moved out. Around 1,000 Croatian citizens obtained German citizenship and were consequently removed from the register of foreigners.

Croatians are the sixth most numerous foreign community in Germany, after Turks, Poles, Syrians, Romanians and Italians.

The number of Croatians with residency in Germany has almost doubled since Croatia joined the EU in 2013.

In 2012, the last year before Croatia's accession to the EU, there were 224,971 Croatians in Germany.

In 2020, the number of people with a foreign passport in Germany rose by 262,000 while in 2019 it grew by 376,000.

Statistics for 2020 show that immigration from EU countries remained stable but immigration from third countries slowed down significantly, which is associated with difficulties related to the coronavirus pandemic.

At the end of 2020, roughly 11.4 million foreigners lived in Germany.

The number of residents from the Western Balkans grew last year as well.

Currently 211,000 nationals of Bosnia and Herzegovina live in Germany, which is around 7,000 more than in the previous year, as do 242,000 Serbians, around 5,000 more than in 2019.

To read more news from Croatia, follow TCN's dedicated page.

Irish Dream or Illusion? Osijek Doctor Returns to Croatia From Ireland

As Poslovni Dnevnik writes on the 13th of November, 2019, following the surge in Croatian nationals heading abroad, which has been and continues to be extensively monitored by the media, there is a growing trend of returning people who have experienced life and work for several years in Western Europe, yet decide to return home to Croatia and try their luck again here at home.

The fact that this trend of return doesn't solely regard people who have gone to Ireland to work in positions that don't require higher education is evidenced by the case of Dr. Delalle, a psychiatrist from Osijek who after three years in Ireland, decided to return home to a Croatian institution, more specifically to KBC Osijek.

According to Glas Slavonije, this doctor, who worked at the aforementioned Osijek hospital since 1986, and was head of child psychiatry at KBC Osijek from 2003 to 2015, says openly that the reason for her departure has never been dissatisfaction with the institution or system, but was solely because of family and financial reasons, and of course, the idea also came from a dose of professional curiosity.

''Within a month, I got a job at an Irish Government hospital, but it was a 45-minute bus and train ride and then another four miles on foot. All this is quite exhausting at my age, especially when you come from Osijek, where everything is at your fingertips,'' recalls Dr. Delalle when recalling some of the problems there.

This psychiatrist also worked for a while in the department for child and adolescent psychiatry in a public government hospital, and although she was initially very enthusiastic, disappointment with the system quickly followed.

In the end, she resigned from this institution, worked for a while in various other institutions, but nostalgia to return home to Croatia still prevailed.

''Financially, there were high incomes and as a psychiatrist you could earn about 5,000 euros a month there, but housing is very expensive and when you pay all the expenses, you're left with an only slightly higher income than you get in Croatia. For a doctor with scientific titles, length of service and on-call duty can also bring you a very nice income here.

It was interesting to go there, see it, experience it all, but I became nostalgic. I wanted to be close to my family and friends again, be where my home was. Thanks to the understanding of the director of KBC Osijek, I was given the opportunity to work at the Clinic for Psychiatry at KBC Osijek again.

''This is an experience that can enrich everyone, but in the end you see that despite all of Croatia's flaws, our system is still much more accessible, more professional, and significantly more empathetic to the needs of the patient,'' Dr. Delalle concluded.

Make sure to follow our dedicated lifestyle page for much more.

Croatian Couple Return from Ireland, Pay Off Debts and Buy Car

Going to work abroad seemed to be the only option, and one Croatian couple spent a year in Ireland but returned to their homeland, just like other people do, as they say.

As Poslovni Dnevnik writes on the 24th of October, 2019, after 20 years in journalism, frustrated by a stressful job, low pay and an exhausting work pace, he decided to start a "new life" along with his wife.

But after just one year, they returned to Croatia. They only went to Ireland to make money to pay off their debts, Deutsche Welle writes.

"It was a very, very good experience. With the fact that I earned something, I gained something that is much more valuable - I lost the fear of existential problems. Because now I know I can go anywhere and live and work there. Nobody here can ever say to me, 'If you don't do it, there's someone who will work for the minimum wage'' again, I've learned to appreciate my time and my work.

I no longer care what I'll do if I lose my job, fail at a company or quit. It's an enormous burden taken from my shoulders. It is a release from the existential fear that most Croatian citizens live in. so I'd recommend everyone to go and try out their skills. If we all had that experience, then it would be a lot different here too,'' Soudil says as he begins the story.

"What was very important in making that decision was the fact that my then girlfriend and now wife was still out of work, so one day we sat down and talked. Many of our friends were already in Ireland. We got in touch with them and got information that we could make three to four times more over there than here. It was a big step, a big decision. You leave your parents, friends, your lifestyle and you're aware that you're going into the unknown and that your life will change completely. Honestly, that decision was not at all easy'' says Soudil.

"We were fortunate not to go to Dublin, we went to Letterkenny which is all the way north and is a small town. The size of the Đakovo, but much more urban and I won't say nicer, because there is nothing nicer to me than this here. I progressed in my work in just a few days. I worked for an agency that rents apartments and homes out and I can only say that I was valid and respected there, and paid properly for the work I did,'' Soudil says.

Immediately upon his arrival, he was offered to work four hours a day, but he refused because work and a better salary were the reasons why he left Croatia. As he says, his job was not demanding, and no one complained about his work ethic or the quality of his work.

"For the last four or five months, I've been doing another job because I realised that I could still make around 40 euros a day, and the money is welcome. It's easy when there are jobs and they treat you properly."

According to Soudil, having Croatian passport is a kind of job ''recommendation'' because the Croats are well known for being hardworking and responsible employees.

He says they repaid all of the debts they had Croatia off in just three months and even managed to buy a car on top of that.

"When we left, we didn't say: We're never returning to Croatia again. We went to see what it was like to make some money too, to cover the foreclosures and debts we had here. We had unpaid bills, foreclosures for parking, electricity... We paid back all the debts that we'd inevitably accumulated in Croatia in three months and we even bought a car,'' says Soudil.

He describes life in Ireland as extremely enjoyable and nice. He says it never happened that he was "missing one more paper" during administrative tasks, an all too common situation when dealing with Croatian state bodies. A person who has lived in Croatia and dealt with any sort of Croatian administration feels a sort of cultural shock when they're greeted kindly at the bank as if by their best friend, even though you're complete stranger, just getting off the plane, Soudil notes.

"At the age of nineteen, I started working in journalism, I was aware that I couldn't do that business there [in Ireland], but I lived in the belief that I didn't really know how to do anything else. My hobby when I was a journalist was a kind of woodworking, processing metal, electrical work... I learned this from the urgent need not to have to pay professionals to do those things and that it was enough for me to just be able to manage. I'm far from being a professional, but I realised that I could do a lot of other things,'' he explains.

He also says that nobody in Ireland ever asked him what school he graduated from and what kind of "papers" he has. Another shock for anyone who has done anything the dreaded Croatian way.

"It's important here if you have a certificate, there, what's important is whether or not you want to work. The employer is ready to invest in you to educate you at their own expense and give you the opportunity according to your abilities. In one whole year, nobody asked me for a diploma, a birth certificate or a certificate of impunity,'' Soudil tells Deutsche Welle.

Upon his return to Croatia he did well. He is now in a better-paying job that he is comfortable with, and as he says, if he ever begins to get sick of it again, he has a job waiting for him in Ireland.

"Ireland is great, but it has one drawback - it's far away. Anyone who works in Munich can spend almost every weekend in Osijek, which is a big deal when nostalgia grabs you,'' he says.

His wife Lea has a slightly different life story - she was born in Germany, lived in London and working in a foreign country is nothing strange to her.

"I found a job right away. I first worked as a maid, and as they saw I knew several foreign languages, they transferred me to the front desk," Lea says.

Despite the nostalgia, she does not regret engaging in the Irish experience. Because, she says, she tried a hundred things she had never had the opportunity to try, see, eat, do...

"With just three weeks of wages we bought a Mini Cooper, second-hand, but you couldn't even do that in your wildest dreams in Croatia. There are big differences in life here and there, but when everything is put on paper, it's still the best at home," concludes Lea.

Make sure to follow our dedicated lifestyle page for more.