Some sources say that the inspiration behind Marija Jurić Zagorka's The Witch of Grič was burnt at the stake on September 4, 1743.

Even if you’re not really into history and know nothing about Zagreb’s history, you must have noticed that witches are a recurring theme in the city – there’s the Grička vještica beer, there are witch-themed city tours, a bistro called Vještica, and our famous writer Marija Jurić-Zagorka has a book called Grička vještica as well. And, let’s be honest, if you’ve ever walked the Upper Town streets at night, you must have noticed that the eerie empty streets seem like the perfect setting for urban legends.

Zagorkin kutak

Even though most people link witch trials to the dark Middle Ages, and there were, in fact, trials as early as the 14th c., they actually reached their peak in the Early Modern Age (15 – 18th c.) and women were burnt at the stakes up until 1757, when Queen Maria Theresa prohibited it.

The hysteria began in 1611 when a small church in Trnava decided that everyone should preach against witchcraft and then the Croatian Parliament officially adopted it as a secular act as well. Official records state that 248 women were burnt at the stake, but who knows just how many met the same fate without it being written down.

All you had to do to start a trial was accuse someone – in most cases a woman – and the court would issue the indictments against you, listing a very creative array of supposed crimes you had committed, and then you’d be put in a cell and tortured, and the more you denied it, the more guilty they thought you were.

The crimes included the usual stuff – flying on a broom, turning into animals or people, sleeping with the devil and animals, killing people by looking at them, turning into the wind, making ointment from murdered children, etc.

The “trials” then gave witches a chance to prove their innocence – you simply had to be lighter than a feather, had a certain blood colour when they hit you on the nose on purpose to judge if you bleed a normal colour or a witch shade, or not float on the surface of water, and endure some of the nastiest types of torture, and there you’d have it – you’d be free. Piece of cake, right?

matica.hr

Of course, there were only five or six cases when someone was acquitted. Oh, and there was the mole/wart test – if you had one, it meant you had a deal with the devil, and the investigators would cut it off, and show it to the court as irrefutable proof, but if you didn’t have one, it still meant you were guilty because you had obviously formed an alliance with the devil and he removed all of them.

The poor women were treated even worse if they happened to be beautiful – priests and other high-ranking members of the city government would rape women in their cells, and then, obviously, this meant that the devil came to their cells disguised as the priest, which just served as further proof that the woman was, in fact, a witch.

Barica belonged to that group – she was a widow who committed the most terrible crime at the time - she was beautiful, smart, and independent, the worst qualities you could have as a woman in the 18th c. She was a very successful baker who was more interested in her business than in the many suitors that she had, which, of course, hurt their ego. Who did this puny baker think she was to turn down powerful and wealthy suitors?

One of the suitors whose pride got hurt was public notary Lack Salej who accused her of witchcraft and found her alleged witch friends who confirmed the theory, claiming that they had seen the mark of the devil on her body. As this was 1743, people in Zagreb were starting to realise that witch trials were wrong, so there was a campaign to free Barica. Her family managed to bribe Lack Salej, at his own request, so he the charges against her were withdrawn and she was released on parole.

However, Salej got only half the amount of money that he had wanted, so he asked for his other half, threatening to accuse Barica again unless he got what he wanted. He then personally led an investigative team to search for the devil’s mark at Barica’s house, searching for it all over her naked body, of course, after which she was forced to give him the other half of the sum he had wanted. Barica accepted because she thought she had nothing to fear as she was innocent. Salej, on the other hand, got exactly what he wanted - the money, and a chance to grope her.

Two months later, Barica dared to accuse Salej of not only asking for a bribe, but also for lewdness and inappropriate behaviour, because no one other than the executioner had the right to search for the mark. The bold woman described what they did to her in detail in her accusation, but what happened after the counter trial, no one knows for sure. One source says that she was burnt at stake afterwards on September 4, 1743, which is probably true, because, let’s face it, there aren’t that many historical records of regular people, especially women, triumphing over powerful men with political connections.

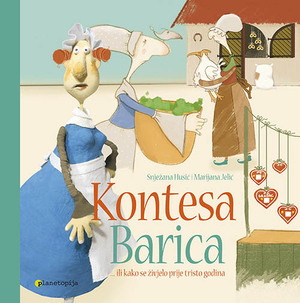

Whatever happened, and we honestly hope that Barica beat the odds and won, Barica lives on in Marija Jurić Zagorka’s The Witch Of Grič, as well as in a children’s book – Kontesa Barica.

But hey, this is only a grain of sand in the desert, and, if you want to find out more, we suggest you book a tour with the experts who know a lot more about the subject than we do - Upper Town Witches Tour or Secret Zagreb Tour are a great place to start.